Cover photo by Adam Mescan

There’s something comforting about urban parks, how they’re a sprint away from home and can spit you out at shops and restaurants. Our 120 Metro Parks offer us everything from a bit of shade and some monkey bars to hiking trails, pools and golf courses. Think of them like lifelong public schools — free to the community with endless opportunities: to take up skateboarding, catch a sunset, refine fishing skills. And the parks themselves continue to grow and change. Metro Parks currently has projects at more than 20 parks. Jefferson Memorial Forest, one of the largest municipally owned urban parks in the country, is 6,600 acres and counting. In June, the Billboard-topping Louisville R&B star Bryson Tiller teamed up with Nike to bring new basketball courts to Wyandotte Park on Taylor Boulevard. The Waterfront Development Corp. announced its master plan for the next phase of Waterfront Park, which will expand west of 10th Street. The 4,000-acre stretch of eastern Jefferson County that has in recent years been groomed as the Parklands of Floyds Fork, which includes a strip of the inching-toward-completion Louisville Loop bike path, is a win in the way of public-private partnerships.

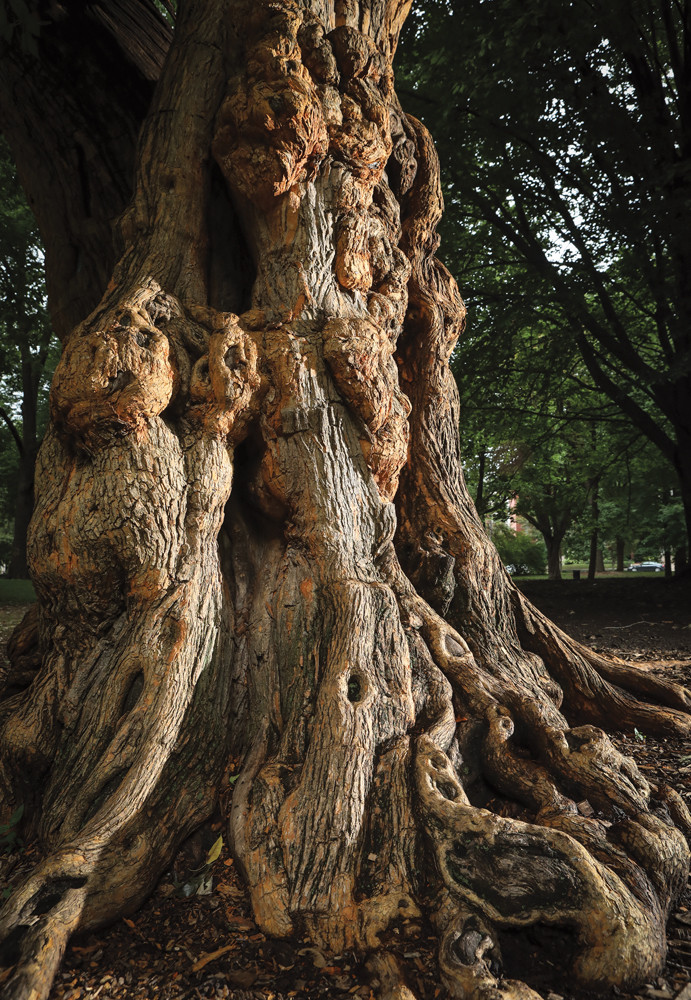

In this package, you’ll learn how to turn a park grill into an upscale restaurant, see a tree that George Rogers Clark supposedly touched, brush up on wilderness survival skills, make the perfect picnic basket and more.

It’s September in Louisville. The perfect time to park yourself in a park.

INDEX

Click to jump to any section.

There is Something for Everyone

6,600 Acres Sit 15 Miles South of Downtown

Metro Parks Helps Serve over 100,000 Meals to Kids a Year

Sarah Traughber is an avid biker who organizes Cyclofemme, a yearly bike ride for women, and “For Women Only, Duh,” a womens-only cycling group. The first time she rode part of the Louisville Loop was near Riverside, the Farnsley-Moremen Landing, the historic farm and house in southwestern Jefferson County. During that first ride on the Loop, she saw a deer in a valley beside the paved lane. “It started running with me. It was this happy moment of reassurance,” Traughber says.

Photo: Sarah Traughber rides the Louisville Loop. // by Jessica Ebelhar

In 2011, Mayor Fischer described the incomplete, 100-mile Louisville Loop as a “wedding ring” that would encircle the city. The first section of the Loop, starting at Zorn Avenue and trailing west parallel to the Ohio River, was completed in 1995, per the Louisville Loop Master Plan. A 10-year plan was initiated in 2013, and when the final path is completed, it will pass through 28 parks and will be within a mile of 72 other parks. Over half of the city’s population will be within one mile of the Loop.

Currently, two sections of the Loop are ready to explore: a 23-mile section called the Ohio River Valley, along the riverfront and western side of the city, and Floyds Fork, a 19-mile section connecting Shelbyville Road and Bardstown Road. “I would love for the Louisville Loop to be complete, and I think that once it is it’s going to bring in more tourism,” Traughber says. “Cyclists want to come here to test that out. I’ve been waiting a long time.”

— Jenny Kiefer

Photo: Iroquois Park overlook. // by Adam Mescan

There is Something for Everyone

The Parklands of Floyds Fork, a 4,000-acre, four-park expanse along eastern Jefferson County with 47 miles of hiking and biking trails, playgrounds and spraygrounds, fishing, event spaces, kayaking, views, history — well, it can all seem daunting. (By contrast, Cherokee Park is 400 acres.) Here’s where to get started.

You’re legit scared you’ll get lost.

Parklands Explorer is a thrice-monthly meet-up covering a different trail each time. This month, bike Beckley Creek Park’s fully paved trail (Sept. 9; 1411 Beckley Creek Pkwy.) or hike Turkey Run Park’s Seaton Valley Trail, an easy natural surface (Sept. 13; 7510, Turkey Run Pkwy.).

You want deep woods minus the road trip.

Hike Limestone Gorge at Broadrun Park (11551 Bardstown Road). The 1.44-mile climb may have you winded, but stop at the bridge over a gorge that, after enough rain, becomes a waterfall. Pro tip: If you truly need an escape, play hooky on a weekday when the park feels more off-the-grid.

You’re not the outdoorsy type but Rover needs to socialize.

The Barklands, in Beckley Creek Park, is an off-leash, fenced-in, members-only dog park. The fire hydrants are a cute touch and you may make a friend or two yourself.

The sound of a paddle hitting water is your idea of bliss.

April through October, canoe or kayak starting at one of six access sites. Don’t have your own? Blue Moon Canoe and Kayak of Kentucky rents boats (and bikes!) out of the John Floyd Community Building in Pope Lick Park (4002 S. Pope Lick Road). From there, explore the Strand, a stretch of woods and wildlife connecting the parks.

You just want a little sun and games.

Beckley Creek Park’s 22-acre Egg Lawn, so named because of its oval shape, offers a .7-mile walking path and space for Frisbee, kites and picnics. Follow the gravel path that goes under the bridge, grab a bench and watch the sunset.

About every week since the mid-’80s, Clifford Turner has run from Chickasaw Park down to the Shawnee Golf Course and back. It takes him about an hour and five minutes to trek the approximately seven-mile route in the West End. “I’m so comfortable running that thing, and my wife really hates it, because I run with my eyes closed a lot,” the longtime west Louisville developer says. “You can get the smell coming off that river, and it’s excellent.”

Turner, a former president of the National Association of Real Estate Brokers, started running to keep the pounds off. “If I didn’t run, I would be just so out of shape,” he says. He’s a member of a running group that foots through Seneca Park, and wherever he travels he looks up local parks, sniffing out routes. When we meet, he’s wearing a T-shirt printed with what looks like a marathon runner’s numbered sign on the front, a memento from the Louisville Triple Crown of Running, a series of three races culminating in the Papa John’s 10-miler. “You’ve got to look your best when you come into (Papa John’s Cardinal Stadium for the finish line), ’cause you’re on closed-circuit television,” Turner says with a laugh.

Photo: Real estate developer Clifford Turner in Shawnee Park. // by Terrence Humphrey

The sexagenarian grew up in Shawnee and Chickasaw parks. He attended Flaget High School, which stood just across from Shawnee Park. Students who smoked — “Not me, of course,” Turner says — had to light up in a little patch in the park. He brings up the famous Dirt Bowl, a summer basketball tournament in Shawnee Park that electrifies west Louisville each year. Somewhere he has a photo of his older brother having an eighth or ninth birthday in the park, a shot that must have been taken in the ’40s. He mentions Fontaine Ferry, until 1964 a whites-only amusement park that used to operate at one end of Shawnee Park. He remembers when protesters burned down the roller rink. “Right there at the end (of Fontaine Ferry) was the big swimming pool. And I can remember sitting there and crying because we wanted to go in and play like the rest of the kids. This was during the segregation period in the ’60s. And my mother used to tell me, ‘Don’t worry about it, your day will come.’ And then, I had to be the one to vote on the change of demographics down in that area, because I was on the Louisville-Jefferson County Planning and Zoning Commission.” A smile peels across Turner’s face. “That was a rich experience,” he says.

— Dylon Jones

6,600 Acres Sit 15 Miles South of Downtown

A dozen kids slick with freshly doused bug spray on gangly bare limbs tip their chins to a pristine blue sky and howl — ah-OOOOH! The echo slips into the beech, oak and 20-some other tree species that stretch beyond the beyond, into thousands of acres of forest that lie along the Jefferson-Bullitt county line.

The howlers are the “Wolfcats,” a team of seven- to nine-year-olds spending a week learning survival skills at Jefferson Memorial Forest. They’ve collected water by running around grassy clearings with bandanas tied to their feet, soaking up morning dew and ringing the haul into a cup. They’ve built shelters out of broken branches, gathered edible plants and built fire. That’s the joy of Jefferson Memorial, an expanse of nature preserved for city folk. Gigantic and wild, accessible to anyone who can travel 15 miles south of downtown, it’s the original Parklands of Floyds Fork.

One by one, each Wolfcat picks up a stick about four feet long, with one end “sharpened” to a dull-scissors point. Each kid props a stick on a shoulder, leans back and throws at a target — paper pictures of a buck, quails and a turkey pasted onto cardboard. A boy in camouflage shorts hits a quail head. “Yay! I made a hole!” he exclaims.

Photo: The "Wolfcats" learn survival skills at Jefferson Memorial Forest. // by Mickie Winters

Jefferson Memorial Forest is a city-owned park. Surprising, right? At 6,600 acres, with 30 miles of hiking trails, it’s 16 Cherokee Parks combined. Naturalists, recreation specialists and maintenance workers help protect the forest, tearing out invasive species, planting butterfly habitats and encouraging the public onto the land for camping, organized hikes and festivals.

No playgrounds or pools here. No swings or slides. Jefferson Memorial’s highlights lean both subtle and grand — frogs croaking on a quiet morning, an assassin bug’s kamikaze plunge onto an unsuspecting shoulder, a mourning dove’s somber coo at dusk. And let’s not forget the five-lined skinks that can startle and the copperheads that can do a lot worse than that. Such is nature, a place worthy of awe and respect. If a dozen city-dwelling Wolfcats didn’t know that at the start of the week, they get it a little more by the end.

— Anne Marshall

On a hot summer afternoon, a few gardeners water their plants at the community garden in Schnitzelburg’s Emerson Park. A sunflower the height of a small tree towers over the other plants. Green beans grow on a trellis. Tomatoes are ripe on the vine, ready to be picked.

Emerson Garden is one of 10 local community gardens managed by the University of Kentucky’s College of Agriculture, Food and Environment. The one in Emerson Park has 80 10-by-20 foot plots that are rented to local residents for $10 a year.

After almost a year on the waitlist, Germantown resident Richard Heil was assigned a plot in Emerson in summer 2016. His plot was in bad shape at first, but before long, his fall garden was packed with cabbage, broccoli and collard greens. “It’s like I could throw something in the ground and it could grow,” Heil says. People plant a little bit of everything in the plots at Emerson Garden. Heil once filled up a five-gallon bucket with red potatoes, and this summer, his garden included sweet potatoes.

Photo: Gardner Richard Heil at Schnitzelburg's Emerson Park. // by Adam Mescan

The gardeners range from young couples to senior citizens. They sometimes have get-togethers in the garden, including breakfasts and potlucks. Gardeners leave vegetables on the shared picnic table and volunteer to water each other’s plants when someone is on vacation. “I enjoy this place so much — all of the people especially,” Heil says.

— Brooke McAfee

OK, so this isn’t a practical trail mix. What’s wrong with indulging in decadence once in a while?

Dark chocolate truffles (Cellar Door), Kentucky honey popcorn and kettle corn (Popcorn Station), granola (Please & Thank You), bourbon-barrel-roasted pecans (Bourbon Barrel Foods).

Photo by Chris Witzke

Metro Parks Helps Serve Over 100,000 Meals to Kids a Year

The parks are much more than vistas and greenery. They’re a living organism of people-centered projects.

Ben Johnson is a parks guy. Well, these days he doesn’t enjoy the parks outside of work much. But he raised his son in the parks, playing ball games and picnicking. Johnson is the assistant director of recreation for Metro Parks, and his office, on the first floor of a repurposed mansion on Sheridan Avenue in Joe Creason Park, off Trevilian Way, looks out at kids on field trips and people climbing on the oversized Adirondack chairs and taking photos. “It’s nothing to see deer,” he says. He hates litter. And don’t get him started on people not picking up after their dogs. He’s seen it happen through his window or on the way to his car and has asked people to please pick it up. “People say, ‘Well, you should supply bags,’ and we have in some areas,” he says. “I don’t agree with that. I didn’t supply you with a dog. That’s more of a cost to the taxpayer. That’s another thing we shouldn’t have to do, another piece of apparatus in the park, some box you have to trim around. No! It’s your dog!”

None of this really has to do with his job title. That involves overseeing a dozen community centers, several senior centers, arts centers, a recreation center, the Mary T. Meagher pool in Crescent Hill, four outdoor pools in the summer, adult and youth athletics, adaptive and inclusive recreation and community partnerships, such as with Dare to Care and Jefferson County Public Schools. Today it involves handling a “situation” that he got a call about over the weekend. “I never turn my phone off,” he says. The centers are open until 9 p.m., but that doesn’t prevent an alarm from going off, a tree limb from coming through a window. “I’ve gotten calls at 2, 3 a.m.,” he says. “If you really want to have an enjoyable visit, go somewhere where something has died in some ductwork.”

It’s not all busted pipes and broken water heaters. Part of the day’s agenda is blocked off with back-to-school events — including free haircuts — at the Southwick and California neighborhood community centers. He has worked to expand the Dare to Care Kids Cafe meals program, which serves dinner every weeknight to kids 18 and younger at each community center — amounting to more than 100,000 meals in a year. “These are not cheese sandwiches. These are not fish sticks,” Johnson says. “I mean, these are roasted chicken, steamed vegetables, potatoes. One of my staffers was like, ‘These are grown-man meals.’”

He worked for the city as assistant director of youth development from 2000 to 2008, then came into the parks role four years ago. He was shocked to learn that Metro Parks was not involved with the Kentucky Derby Festival, so he partnered with it on the Bed Races and the department now rides in the Pegasus Parade.

Noticing a need for better community/police relations, Johnson reached out to LMPD to start a monthly youth chat. “Then Mike Brown happened,” he says, mentioning the unarmed, 18-year-old African-American who was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. Metro Parks and LMPD began the program soon after. On the third Thursday of the month, several neighborhood police officers come to one of the community centers to answer kids’ questions. Johnson’s guidelines: Ask anything you want as long as you do so respectfully; you do not have to like the answer but you have to accept the answer. He then has a young person from the community MC, to encourage public speaking and leadership. He recalls one exchange of particularly tough questions:

“Have you ever shot anybody?” a kid asked.

“Yeah, I have,” the officer replied.

“Well, what happened?”

“I killed him.”

“Why’d you have to shoot him?”

“Because he pulled a weapon on me.”

“But that didn’t mean you had to shoot him.”

“Son, you don’t understand. He pulled a weapon.”

Johnson says, “At that point, the mood of the room changed, but the officer handled it well.” Each month features a special unit — robotics, equestrian, SWAT, K9, bomb squad — but the floor is open to all questions. The chats have drawn as few as seven and as many as 110.

A sign on Johnson’s desk reads: “Why not?” “People are too quick to say we can’t do anything,” he says. Another one is a “no” symbol covering the words “But we’ve always done it that way.” He often uses it as the watermark or background in the agenda for staff meetings. “It’s kind of hokey,” Johnson says, “but if I can get you to walk out of here thinking a little bit different, I’ve done my job.”

— Mary Chellis Austin

Metro Parks administrator Mesude Ozyurekoglu and forestry manager Mike Blankenship oversee the more than 30,000 trees that stand in our parks system’s recreational areas. We asked them to pick a few old, big, interesting trees and tell us about them. Well, Ozyurekoglu chose seven — and has even more on her list when she and Blankenship take me on a tour on a summer morning. “You made me think about possibly coming up with a program for Metro Parks on special trees or historic or aesthetically valuable trees — to open it up to the public,” Ozyurekoglu says. “I need to run that idea through administration.”

In Central Park alone, Ozyurekoglu shows me a tulip poplar, a swamp white oak, and a pin oak, which the Kentucky Arborists Association has used for its annual tree-climbing competition. She estimates that a northern red oak is about 66 inches in diameter and 200 years old. “Doesn’t mean nothing’s gonna happen to it,” she says. “It’s the nature, you know? Sometimes with adverse weather conditions, we may have trees uprooting because of invisible symptoms, root problems or disease. There are other factors like air pollution and the heat-island effect. It’s like humans. We can be a healthy senior person, 90 years old, everything is fine; you’re slow but you’re still healthy. All of a sudden you may just shut down. I see it as a beginning of a new life because eventually we will lose them. We are removing around 300 trees a year and are trying to plant 1,000-plus.”

— MCA

Photo: Osage orange tree at Central Park. // by Jessica Ebelhar

CENTRAL PARK

Osage orange

Ozyurekoglu: “This tree is pretty old — 200 years? In the wintertime it will have fruit, big-sized balls. It’s not the perfect urban forest tree, just having that dropping on your head…”

Blankenship: “Many, many years ago they used these trees as fence trees because they didn’t have fences to keep in cattle. The limbs, when they’re young, have thorns. You get close to them, they will bite you. The old saying is, people would collect the fruit and put them under their house or in their closet to keep spiders out.”

Photo: Bald cypress tree at George Rogers Clark Park. // by Jessica Ebelhar

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK PARK

Bald cypress, with a plaque that reads: “According to legend, George Rogers Clark thrust his riding crop into the ground at this spot and from it grew the cypress tree.”

Ozyurekoglu: “If George Rogers Clark did what this says — he died in 1818, so it’s 200 years-plus. There is nothing else even close to this one. At some point it lost its leader branch and developed the side branches.”

Blankenship: “Lightning or wind blew the top off it, so it sheared it off right there and started re-sprouting back.”

Ozyurekoglu: “I love this park. It’s more of a natural, woodland-type park. I think those Olmsted parks like Cherokee, Shawnee, Seneca — those are more advertised, more known. But this is one of those areas that I love. It’s beautiful.”

Photo: Ash tree at Chickasaw Park. // by Jessica Ebelhar

CHICKASAW PARK

Ash

Ozyurekoglu: “All ash trees are subject to the emerald ash borer. Unless you treat them lifelong, the tree will die. Obviously we cannot treat several thousand trees in this system, so we picked some of the healthiest, geographically represented ash trees and started our treatment program in 2010. We all would like to have more resources. Well, we’ve learned that complaining about not having enough resources is not gonna go anywhere, so let’s find something else.

“The active ingredient is emamectin benzoate. It’s basically insecticide. Scientists don’t know the whole outcome of the treatment yet. It’s proven that the treatment works. Even mechanically drilling into trees hurts trees. When we first had the infestation, the population of ash trees was more than 3,000, representing 13 percent of the whole canopy. It’s down to 10 percent now with our removals. That’s why diversity is so important. Who knows what’s gonna happen next.”

It’s easy to slip into contemplation at Riverview Park. Even if you don’t mean to. Even if you’re just passing time on a bench swing facing the Ohio River, one arm slung back, toes providing the momentum needed for a gentle back and forth. On a recent afternoon here in southwestern Jefferson County, a light breeze dimples the water. Across the way, southern Indiana’s rolling green hills look so lush and steep they could trick a Midwesterner into believing they’re mountains.

Photo: Riverview Park // by Mickie Winters

Look south, downriver. A couple wades past rocks and into the water looking like love-struck teenagers. She jumps into his arms. He splashes her, their flirtations punctuated by playful squeals. Oozy mud bubbles between their toes. So she starts to swim. Walk toward them, a little closer. The couple isn’t so young, somewhere in their 30s and “married for four years,” they say. They climb out of the river, he in white swim trunks and she in a dark tank top and short-shorts. Their wet shoulders nearly touch as they sit on damp dirt. Crushed water bottles, empty beer cases, a woman’s bathing suit and infinite cigarette butts scattered along the riverbank. But if they mind at all, they’re looking past all that now. Quietly, their eyes settle out on that view.

— AM

A few things Shawn Ward has that you probably do not: Japanese pork chops, shishito peppers, juicy ripe peaches from the tree at his home in Lyndon. All of that and, oh, nearly two decades of experience as chef at Jack Fry’s and for the past couple of years at his own restaurant, Ward 426 on Baxter Avenue. What you do have is access to a pretty impressive grill — at least Ward thinks so. “Wow, that’s a lot nicer than I expected,” Ward says on a breezy day in Tyler Park in the Highlands. The grill — one of many found at more than 30 of the city’s parks — is about three feet wide and has an adjustable grate. “I had a panic attack last night because I thought (the grill) would be this big,” he says, indicating a space between his hands that’s about a foot wide. “You could smoke, well, maybe not smoke, but you could grill something on here for hours and hours and hours and you could probably feed 50 people on this grill. There are better grills. But for free? And you got all this?” he says, looking around at the trees aglow with afternoon sun.

Photo: Chef Shawn Ward uses one of several grills in Tyler Park. // by Jessica Ebelhar

We’ve asked him here today to grill something — anything — so that maybe the next time we want to host a gathering at the park we’ll know how to feed a crowd. Ward shows up in black pants and his white chef’s coat, with his knife and tool bag and bins of ingredients. For the main course: pork chop with charred shishito peppers, cooked on the grill in olive oil with garlic, heirloom tomatoes and basil and topped with ricotta salata. For dessert: grilled peaches drizzled with bourbon and maple syrup, topped with mascarpone and honey whipped cream, homemade granola and blackberries. He lights the charcoal with a butane-fueled torch (something else you may not have, though a regular lighter will do) and starts the show, which at times becomes an actual show to passersby.

Photo: Pork chop with charred shishito peppers, garlic, heirloom tomatoes, basil and ricotta salata.

Grilled peaches with bourbon-maple syrup, mascarpone-honey whipped cream, bacon bits and blackberries. // by Jessica Ebelhar

Adjusting the grate regulates temperature. “If you put the meat on the grill and it starts to sizzle, it’s too hot. If you have a thick cut of meat, you want to cook it at a high temperature but not too high of a temperature where you burn the outside before you cook the inside.”

A few grilling tips from Ward:

Paper plates are for hot dogs. “If you had that pork chop on a paper plate it’d be a disaster. If you’re gonna spend $25 on a piece of meat, would you want to eat it on a paper plate?”

A nice cut of meat from the butcher shop doesn’t need a lot of seasoning. “You don’t want to season (the chop) a lot because there’s a lot of flavor already. See the marbling in there?”

A word on shishito peppers: “They’re delicious but they call it a surprise pepper because one out of 15 or 20 will be completely hot. The ricotta salata is kind of mild but will offset the spiciness of the peppers.”

Don’t follow a recipe. “Oh, shoot, I brought the wrong container. That’s candied bacon. We’ll have to leave the granola off the peaches. You know what? We could put candied bacon on it. That would be really good, actually.”

— MCA

Picnic basket ($65, Scout); blanket ($70, Just Creations); fleur-de-lis bottle opener ($6, Gifthorse); smoked turkey sandwich (provolone, Düsseldorf mustard, lettuce and tomato, on sourdough) and Spudz chips from Morris’ Deli; Mid-City Underground sandwich (Jarlsberg Swiss, scallion cream cheese, lettuce, tomato, cucumbers, sprouts, carrots and lemon dill mayo, on wheat) from Stevens & Stevens; farfalle pasta salad (Lotsa Pasta); June apples and sliced carrots and celery (Paul’s Fruit Market); Ale-8-One and Butchertown Cream Soda; chocolate chip cookies (Please & Thank You).

It takes about a minute, something like 99 steps, to walk the perimeter of the smallest park in Louisville. A little wedge of green at the intersection of Reutlinger and Ellison Avenues in Germantown, Gnadinger Park, donated to the city by the Gnadinger family in the late ’70s, occupies a mere 2,700 square feet of land. The metro parks website lists its acreage as a puny .03.

Photo: Gnadinger Park in Germantown. // by Terrence Humphrey

It’s a rule of literature that, in the short form, every detail taking up limited real estate balloons in importance. If we apply this thinking to Gnadinger Park, its three trees (two thick and towering, one head-high and spidery), two wooden benches (green paint flaking away), brick walkway and single, bright-blue trash can become weighty symbols. Looking down at the walkway, I thought of my grandfather. He’s 82 and slowing now, but he worked construction most of his life. He must have laid thousands of bricks like these, working at the same time they were installed. I made that, he told me once, pointing at a parking lot. I’d have never known. Standing in Gnadinger Park, I get the sense that the walkway below me is a stone curtain, the men who built it both immortalized and obscured by their work, its enduring, blank gray surface.

There’s a tiny, triangular brick at one corner, the same basic shape as the whole park. I can’t quite pull it up to look.

— Dylon Jones

Photo: Plans are optional. // by Terrence Humphrey

Democracy reigns — for runners, Frisbee tossers, relaxation seekers — in our rich network of parks.

I run. Humid morning air sticks to skin, to the mansions guiding me into Cherokee Park, into its wooded, chirping insides where the air dips a few degrees. Sunlight dims beneath dense tree canopy. A sharp right turn and I’d do my time on Cherokee’s 2.4-mile Scenic Loop, a popular paved running route. But I swear allegiance to the miles of dirt paths.

I never run with music. I listen instead to my odd shuffle, left foot pounding, right foot light. THUD-plop, THUD-plop. Plans and schedules, big dreams and recent disappointments come and go. But I really just try to run and listen: to my panting, to the last of the summer cicadas, to walkers sharing gossip on the nearby loop, to songs in the branches and bugs buzzing by, mocking my pace.

I run past Hogan’s Fountain, by a bushy, overheated dog gratefully licking from puddles collecting beneath. I think of Mother’s Day and the many families picnicking on blankets in islands of shade. I remember a large Muslim family exiting the gazebo, pulling out rugs and kneeling down for prayer. I remember a family rolling speakers next to their grills, raising the volume to a thumping level, joyous Reggaeton. Footballs were thrown, Frisbees tossed. On another visit to Hogan’s Fountain, I saw children encouraging their rusty-colored Labradoodle to scale play equipment, giggles bursting as it plunged down a slide. Louisville often shows so beautifully on top of that hill.

I run to an orderly maze of trails, past a hunched stick teepee and a tree that’s carved from base to the height of a lanky teen on tiptoes — EM + WM, KW + AW, T.T. 86. In white pen, a remembrance: RIP Lemon 2Buk. I run past redbuds and oaks, May apple and wild lemon trees, past three birdwatchers lost in hushed admiration of a creature, my THUD-plop rattling their peace. I slow to navigate a rocky dip and leap carefully over a snail. It rained yesterday! Are you lost? Must be important. My foot — the right one prone to strike light — grazes a knot in the trail and the heavy left catches my fall. I’ve emerged from these trails hobbling, knees scraped and dirty. Just old roots reminding me who was here first. I run past a thin stretch of Beargrass Creek that will dry to mud in a minute. Black-eyed Susans line my path out of the park, a silent, vibrant crowd waiting for me near the finish.

— AM

Louisville Magazine

Photographer: David Boone

Instagram: @louisvillefromabove | Twitter: @502fromabove

This story originally appeared in the September 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. Click here to subscribe. To find out where to buy a copy, click here.