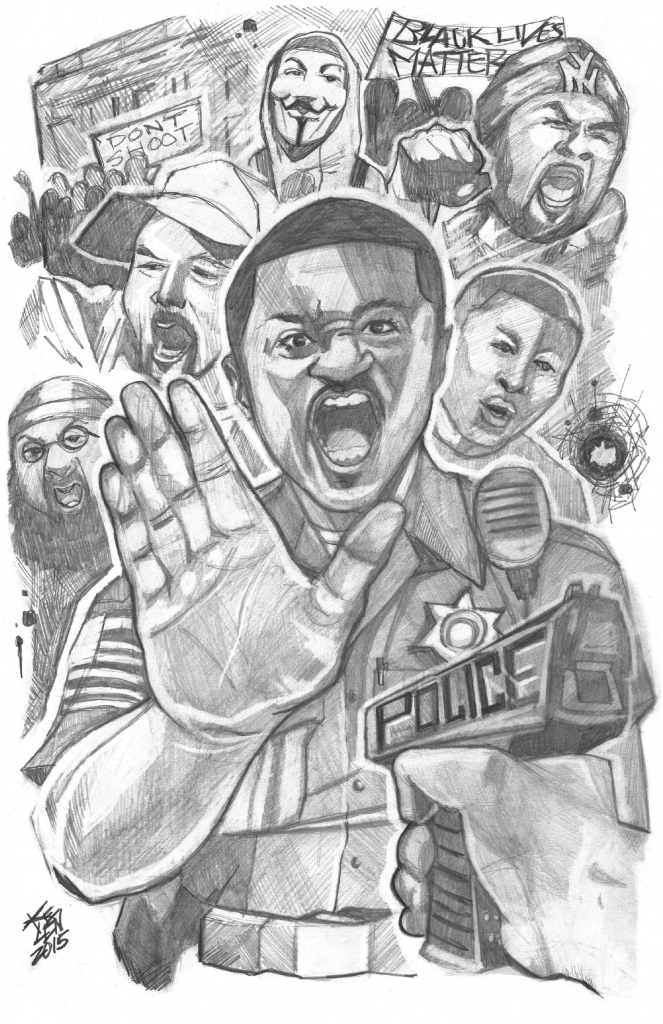

By Phillip M. Bailey

Illustration by Kevlen Goodner

Editor's note: A lot has changed since we ran this column in February 2015. David James is now in his third term as president of Metro Council. Lt. Richard Pearson retired. Former deputy chief of police Yvette Gentry became the director of Youth Detention and Prevention Services the month after we published this piece, and in September 2015, mayor Fischer named her Chief of Community Building, a position overseeing a range of city departments that she held until stepping down in 2017. Just this week, Fischer fired police chief Steve Conrad because the officers involved in the shooting of David McAtee did not turn on their body cameras. (Conrad had announced in May that he would retire at the end of June, and will still receive his pension.)

But even though so much has shifted, this column reads like it was written yesterday. Then it was Michael Brown, Tamir Rice and Eric Garner. Today it's George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and David McAtee. And Black officers are still navigating the "dual identity" Phillip Bailey (now a reporter at the Courier-Journal) wrote about. Yesterday, the C-J shared a Facebook post written by a Black, 27-year-old LMPD officer named Christian Lewis following McAtee's death. In it, Lewis echoed what some officers said in this piece over five years ago: "I know I can say that all Black officers are in a tough spot right now. We're damned if we speak up too much on social media, or damned for not enough."

Louisville Magazine has reached out to LMPD for more current statistics on racial diversity within the department. We will update this piece when more information is available.

Officer Yvette Gentry remembers responding to a robbery call early in her career at a fast-food restaurant near 39th and Market streets. A man sprinting in the opposite direction ft the suspect’s description: Black male, late 20s. Gentry yanked the steering wheel left, throwing the squad car into a sharp U-turn, and leapt from the vehicle. It was the mid-’90s, her second year on the job, and she hadn’t yet learned the one-way streets and alleyways of her west Louisville beat. But Gentry, a former Central High School track runner, kept up with the suspect. It was about 1 a.m. as she cut through dimly lit backyards, hurdled a chain-link fence.

“Then I didn’t see him anymore,” Gentry says. “I didn’t realize he had laid down. And when he got up, he had a gun.”

She drew her 9 mm Smith & Wesson. “Police!” she yelled. “Don’t shoot! Drop your weapon!” Seconds ticked. He complied.

On the ride to jail, Gentry said to the man, “Do you know how close we came to somebody not being in this damn car?” Recalling the memory, she says he was apologetic: “Man, I don’t want to kill nobody. I wasn’t going to shoot you.”

“Actually a nice guy when I got him in the car and talked to him,” Gentry says. “Just a desperate guy trying to figure out how he was going to feed his people tomorrow.”

America’s Black police officers are largely absent from the discussion ignited by protests of controversial deaths: 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland and 43-year-old Eric Garner in New York — all Black, unarmed and killed by police.

Several of Louisville’s Black cops who spoke to me for this column (many on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal) say they feel ostracized by the Black community but bristle at racial slights from their “blue” brothers and sisters. All voice concern about the lack of minority representation in the police force, particularly in the high-profile units.

“It’s important for the police department to look like the community,” says University of Louisville Police Major and Metro Councilman David James, whose Sixth District stretches across Old Louisville. Louisville’s police force is much whiter than the population it serves. In a city that is nearly a quarter African- American, about 11 percent of LMPD’s approximately 1,240 sworn officers are Black. It gets whiter farther up the leadership ladder. Of the 231 police in the “commanding officer ranks” (sergeants, lieutenants, majors, etc.), 7 percent are Black.

James, a former Louisville narcotics detective who used to be head of the city’s Fraternal Order of Police, remembers when he was walking home from Butler High School as a kid. He was still wearing his marching-band uniform when he says a white officer pulled up and, without warning, threw him on the hood of the police cruiser. “My motivation for becoming a police officer was because I hated police,” James says.

“I remember growing up watching the riots, the marches, the water hoses and the dogs. I saw police doing bad things to people like me. In my mind, I thought if I became a police officer I would be able to stop them from doing stuff like that to people who looked like me.”

That dual identity came into focus during an incident in the early 1990s, after the city and county drug units merged. James remembers while he was arresting a Black suspect for allegedly dealing cocaine, a county officer, who was white, spouted off in front of several other officers and residents. “He says, ‘Nigger, shut up’ (to the suspect). And repeated, ‘Hey, nigger, I said shut the fuck up.’ It went through me like barbed wire,” James says. “We get the handcuffs on and get the guy in the car, and I said to the officer, ‘I’m not sure how you all in the county do things, but that shit ain’t cool. Don’t ever do that again.’”

“A lot of Black officers are afraid to speak out,” says one decorated veteran LMPD officer who works in the Second Division, which covers swaths of west Louisville. “I can see why we don’t want to bring up a sore subject for white officers with what’s going on right now. It is job suicide. They will mark you a radical. But it’s time for us to stand up. If not, we’re protecting a criminal with a badge.”

“I’m a supporter of the protestors,” a Black LMPD detective says when asked about “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” demonstrations in Louisville that have stopped traffic along Main Street and Bardstown and Shelbyville roads. Those same activists have marched through St. Matthews Mall and, during Christmastime at Light Up Middletown, stood silently with signs quoting the dying words of police-shooting victims. “There has to be a change because there’s something broken here,” the detective says. “There’s a history of abuse of the Black community.”

Lt. Richard Pearson, a 22-year veteran who oversees the Second Division nightshift, says the protestors are “foolish.” He adds that, over the years, Black residents have given him an earful. “If I had a nickel for every time I’ve been called ‘house nigger’ or ‘Uncle Tom’ or ‘sellout,’ I’d be a rich, rich man,” he says. “I keep asking them, ‘As a young Black male, do you want the entire police department to be white? Or do you want Black officers, and if so, why would you bring them down?’ You never get any support from our people, and it’s a shame.”

Pearson also criticizes the fact that so few African-Americans have advanced under Chief Steve Conrad’s LMPD. “There is not one Black commanding officer in Metro Narcotics — not one,” Pearson says. “I think in the entire Narcotics Division, there’s only maybe two Black officers” — there are three, out of 35 — “and I don’t see how you can justify that, how you can rationalize a unit like that not having hardly any Blacks in it and no Black commanders.” The homicide unit also has no African-American commanders. (Last May, a jury ruled against Pearson in a lawsuit that claimed LMPD unfairly passed him over for promotions.)

“They try to appease Black officers by promoting us sparingly and then putting us where they want us — as opposed to where we deserve to be — so they can avoid the stigma of not promoting,” Pearson says. “This chief we have now is the crown prince of it.”

An LMPD spokesman says the department’s union contract forbids Conrad from making direct assignments to specialized units, including Narcotics and Homicide. Conrad can appoint certain positions such as assistant chief and has sole discretion for promoting the police ranks of major and above.

After nearly two decades in Louisville law enforcement, Gentry retired last December at age 44. She was an officer born in the Smoketown neighborhood, was respected among the rank-and-file and community activists, and became LMPD’s first Black female deputy chief. It was a rare accomplishment. Of the 125 officers who are Black, 15 are women. Of the 45 would-be officers in this year’s recruitment class, eight are Black and just one is a Black female.

When former Chief Robert White, an African-American, stepped down in 2011, Gentry applied to succeed him, and many lobbied the mayor to appoint her to the top spot. It is hard to imagine Gentry leaving LMPD if she’d gotten the job.

“There’s nowhere else for me to move upward in that police department,” says Gentry, who insists she’s “happily retired” and “not looking back.” Those close to her believe she’ll end up in law enforcement in another city. Others hope she makes a bid for Jefferson County sheriff in a few years. “I’m not necessarily done with law enforcement,” she says.

This article originally ran in the February 2015 issue of Louisville Magazine under the title “Black and Blue.”