By Charles Wolford

Photos by Bill Luster

In the distance, the Ark was perched upon a plateau, as if the floodwaters had just receded. Tree trunks, shaved of branches and lopped at the ends, had been angled upward, steadying the boat’s corners. From this height, they looked like toothpicks, and the Ark seemed no bigger than a raft drifting below the tidal wave of the sky.

I was standing in the parking lot of Ark Encounter, a life-sized re-creation of the biblical Noah’s Ark, built outside Williamstown, Kentucky, about an hour and a half northeast of Louisville. This was its opening day, July 7, 2016, and around me people streamed between rows of cars and wooden pillars that held up the roof of a building that resembled an unfinished stable, channeling into a maze of ropes to a wall punched with ticket windows, above which a sign listed the prices: $40 for an adult aged 13 to 59. Cheaper than Disneyland.

The mastermind behind Ark Encounter is Ken Ham, the famed public school science teacher from Australia who became a leading proponent of “young-Earth creationism,” which holds that God created the universe 6,000 years ago — that Earth is not 4.5 billion years old. After forming the ministry Answers in Genesis, Ham moved to the States and headquartered in Kentucky because it’s within a one-day drive of two-thirds of the U.S. population.

“America is the center of the Christian world and the business world, and this is a tremendous place to be, geographically,” Ham told me over the phone in his gravelly, almost purring Brisbane accent. “Plus, we didn’t want to be near other theme parks, like Universal and Disney.”

On the bus that couriered people from the parking lot to the Ark, the crowds were chattering, and the driver, without an intercom, was practically shouting against the hubbub: “The Ark is built 15 feet off the ground and is seven stories tall….It was completed in 2016; the initial project started in 2007….Behind the Ark is our fascinating Ararat petting zoo….Please take note of where you parked, because we’ll be leaving the modern world and going back in time, to Noah’s world….”

“Golly,” someone said when the Ark came into view. “Oh my goodness.”

“Four guys built that,” another man said. “Unbelievable, isn’t it?”

The doors flapped open and we spilled onto a roundabout, where a loop of buses unloaded crowds and zoomed out to let in more buses. A sign nearby advertised SCREAMING EAGLE AERIAL ADVENTURES ZIP LINE TICKETS HERE. A man in a safari hat holding his little boy’s hand pointed toward the Ark: “This is a symbol of the mercy of God and also the judgment of God, because God gave us the world but we ruined it and He saved only the righteous.…”

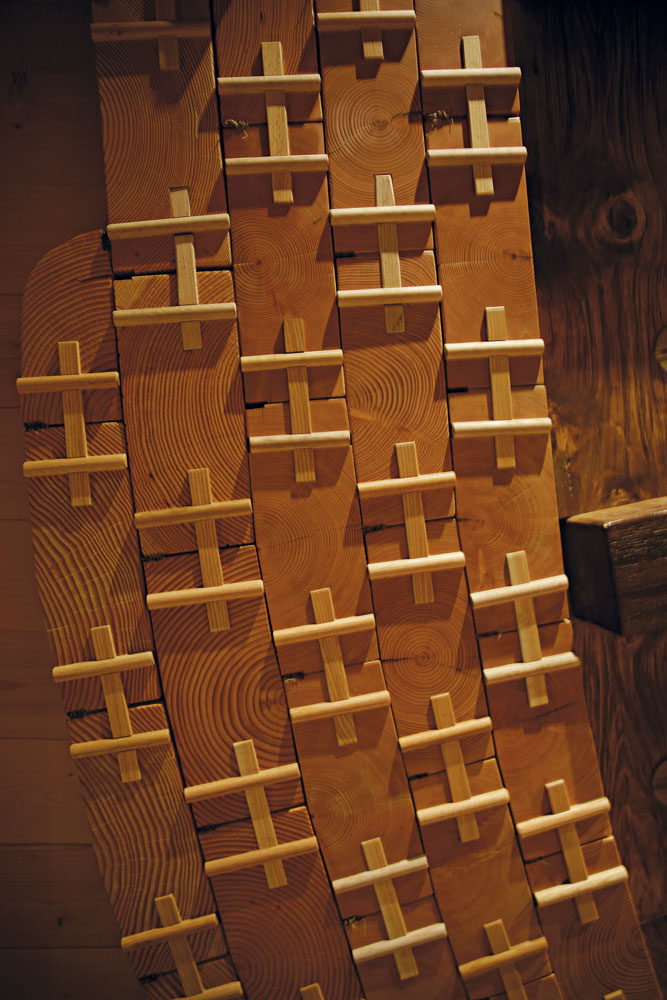

In Genesis, God chose Noah to build the Ark because “he was alone righteous and blameless in his time.” He was also 600 years old, and his sons (Ham, Shem, Japheth) helped him with the construction. God commanded that “the length of the Ark shall be 300 cubits, the breadth of it 50 cubits, and the height of it 30 cubits.” Answers in Genesis used the ancient Hebrew “royal cubit” (20.4 inches long) and scaled the structure to be 51 feet high, 85 feet wide and 510 feet long — 3.3 million board feet of timber. As Patrick Marsh, VP of design and attractions, told me, “It’s the largest timber-frame structure in the U.S., and possibly in the world.”

Like a grain silo laid flat on its side, the Ark encompassed the horizon. Made of a blond-hued wood, it was smooth and rounded, the sides sloping to sharp points at the ends. A door raised about 30 feet off the ground was impressed into the structure’s façade — the door, through which the animals were meant to file. (“And the door of the ark shalt thou set in the side thereof,” God told Noah, “with lower, second, and third stories shalt thou make it.”) When I visited the Ark again in September, a ramp that sloped from the door had been added.

“Four guys,” the man from the bus said. “Something, ain’t it?”

The blacktop path curved past a wooden fence. Slipping around it, I joined the line. Most seemed to be white men between 30 and 70. I scanned their shirts: “Freedom Baptist Church,” “Cross Country Evangelism,” “Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey.” The man in front of me had on jeans and suspenders and a flannel shirt checkered blue and white, and a red “Make America Great Again” hat.

The hull of the Ark rested atop a forest of concrete pillars, between which the crowds flowed, massing into the labyrinth of turnstiles that spread out with an expansiveness that reminded me of Customs queues on Ellis Island. Fans beat the muggy air. The floor was cement, but painted beige and scoured to resemble packed earth. Stacked along the margins were crates that I guessed represented the luggage that Noah and his family loaded for the voyage — maps and twine-wrapped bundles and axes and mallets and hammers in an open box big as a coffin. Speakers hooked to the ceiling dripped out an olive-oil muzak of those snake-charming, belly-dancing chords that always seem to writhe during aerial tracking shots of Near Eastern bazaars in Hollywood blockbusters.

Getting inside took about 45 minutes — we wound through the maze and up a ramp to a landing with a green screen, where a teenager with a camera slung over his neck was saying, “Pictures? Pictures? Any pictures today, folks?”

We moved past him, herding inside the Ark.

As the walls and ceiling closed around us, I felt like I was entering a mind — a tortured mind, because the foyer twisted down a hall that led to a cave-like space of plaster walls and fluorescent panels, flickering to mimic lightning, while a soundtrack roared out thunder and blasts of wind, as if tsunamis were exploding out of fissures that cleaved the globe. Somewhere within the violence of the storm I heard men and women drowning at sea — wails of the dying lost under the waves.

I kept turning down the hall, into an obstacle course of boxlike cages ventilated with grilles of bamboo thatching, on stands that rose higher than our heads. This was the gallery where the Ark’s smaller animals nested. The lighting was dim, and the noises replicated a stroll through the Amazon basin — squawks and deep-throated screeches and claws scampering across wooden floors.

I entered an open space like a refurbished granary. The wracking thunder and jungle cacophony faded, and that slow beat of cymbals that had been playing as I stood in line resumed, like braceleted arms beckoning us into some sultan’s perfumed chamber. EXIT signs flared red against blond boards, gleaming under chandeliers that looked like they could have been bought at some nouveau-barbaric section of Pottery Barn. (These lights were electric, but an exhibit I saw surmised that, on the real Ark, Noah might have used lamps that burned olive oil.)

Cages larger than the ones I’d already seen had been built into the walls, and inside the first one I peered into were two models of what looked like huge prehistoric turtles without shells. Gray, the color of rump roast left too long in a freezer, they seemed remarkably lifelike. For a moment, I expected them to turn their depthless eyes toward me, or wobble over and nuzzle my hand. Deer, gazelles, warthogs, azhdarchids all stared out at the crowds from within other cages. Patrick Marsh later explained how his team designed the animals. If they wanted to make a hippo, they created the taxidermy form on the computer, carved it out of foam, built a hard coat over it and poked each of its hairs into place. “They’re all hand-sculpted,” Marsh said. “Every animal takes about two months to do.”

Marsh used to work for Universal Studios, where he was the art director for the King Kong attraction, among others, before joining Answers in Genesis. “I believe in what the Bible has to say,” Marsh told me. “So it wasn’t too big a jump going from Los Angeles to here. It’s just a little more outside the mainstream than Universal Studios.” The people under him are qualified to be hired in the movie industry, and some 50 artists and sculptors worked together in the shop — 24 hours a day leading up to the opening. “We’re still not finished,” Marsh said. “We’ve been working on the Ark for probably close to 10 years, from the first concept to what you see today.”

I read the museum-style posters on the walls. Fish would have been fine during the flood, one said, because a lot of marine species thrive in both freshwater and saltwater; polar bears would have survived, too, because they don’t need to live in a subzero climate (“many warm-weather zoos house polar bears”); large animals could fit in the Ark given that it was bigger than people think, and most dinosaurs “were smaller than bison, even as adults”; and 99 percent of all species have not gone extinct, as evolutionary biologists claim: “The amount of documented extinct species only numbers in the thousands — not in the millions or billions.”

The first deck didn’t have much on it — cages and posters, a snack bar that sold chips and soda and coffee, platforms recessed into the walls stuffed with hemp bags (probably filled with some species-neutral foodstuff like grain). Walking the floor took me less than two minutes. I made a few loops before climbing the wheelchair-accessible ramps that zigzagged up through the levels. On the second deck, people posed in front of a huge door, their kids grasping the handles and swinging upside-down. Nearby, a poster (“The Door”) read: “Noah and his family entering the Ark through the door reminds us of the good news of Jesus Christ. Just as God judged the world with the Flood, He will judge it again, but the final judgment will be by fire. We have all sinned against our Creator and deserve the penalty of death (Revelation 20:14).” Underneath that: I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.

Rows of stalls like those in barns featured exhibits, including one called “Fairytale Ark.” Above the entrance was a wooden craft stuffed with animals that looked like Disney characters — a monkey swinging from a giraffe’s tail; a toucan perched on an elephant whose trunk trumpeted the air, white birds sheering off into a rainbow. Children’s books — Ark Angels, Lark in the Ark, Noah’s Noisy Ark — lined shelves behind glass, and two signs hung on the walls. A serpent with a pulpy eye and red scales like bloody metal coiled around one sign, tongue flashing near the words: “If I can convince you that the Flood was not real, then I can convince you that heaven and hell were not real.” Opposite, the other sign read: “And everyone died except the 8 people in the Ark.”

Outside the entrance to another exhibit, “The Pre-Flood World,” a mural showed silhouettes of a man and a woman standing waist-deep in a waterfall pool, while a herd of brachiosauri towered over a forest. Posters displayed the days of creation, all the way to Day Six, when mastodons and a wild dog and two baby dinosaurs and that same clique of brachiosauri gathered around Adam and Eve, who looked northern European and in shape, like they went to the gym a lot and had cut out carbs. (Later, at the Creation Museum, Answers in Genesis’ other major project, I learned that animals in Eden were vegetarian, which explained Adam and Eve’s low body-fat percentage.) The Pre-Flood World was a corridor of drywall that twisted past panels that read “God Creates the Perfect World” and “After creating Adam, the Lord made Eve from Adam’s rib to be his perfect companion.” Side by side, Adam and Eve were holding each other, gazing up at a necklace of stars.

Then came “The Fall: Man’s Rebellion Corrupts Creation.” Winding through the branches, the serpent from the Fairytale Ark slithered its tongue at Eve’s back while she reached up for the fruit of the tree. “Death” headed another poster: “Adam’s sin brought death and the Curse into this world.” The other panels went on like that — “The Expulsion: God Banishes Adam and Eve,” “New Life: God Revives Man’s Hope,” “First Murder: Cain Murders Abel.” I fell behind three women ushering a group of little boys through the exhibit, pointing to posters and saying, “What happened here?”

“Cain murdered Abel,” the children sang.

“That’s right — Cain murdered Abel. It was crazy there for a minute.”

Gold letters spaced above another series of posters proclaimed: “Descent into Darkness.” The soundtrack blared out snorting horses, crackling kindling, shrieking men. One of the posters, “Giants,” showed an ogreish figure with jagged teeth charging forward with a club raised over his bald, scarred head. In front of me, a woman with a pageboy haircut held the hand of a little boy. Pointing, she said, “There were once giants in the Earth. Did you know that, buddy?”

“There were?” the boy said.

“A long time ago. Yep. It’s in the Bible.”

“Violence” was the last poster. Across the canvas swarmed Visigoth armies bristling with swords and shields and firelit lances. An arrow thudded into a soldier’s chest. A grunt snarled as he skewered a man through the gut. One of the women leading the little boys said to another one, “Morgan, this makes me want to go re-read my Bible.”

“Excessive Hedonism: Living for Pleasure” (“All flesh had corrupted its way on the earth”) showed a street scene that could have been plucked out of a Moroccan casbah. Three men in togas haggled with women who had the skin tone and getup of medieval Italian duchesses, all of them standing under a store awning. Morgan pointed to the poster. “So, pleasure — it was all flesh.” (The children stared up at her.) “People was just doing whatever they wanted to do.”

“The devil uses sin to separate you from God,” another of the women said.

Around the corner, built into a wall behind a glass panel, a diorama depicted what appeared to be a Mesopotamian rooftop party. Women, six inches tall, with dark plaited hair and dressed in two-piece loincloth bikinis, were frozen mid-gyration. Someone strummed a standing harp. People lounging on couches arranged around a fire brazier raised chalices in salute. The woman with the pageboy lifted her son. “Look at what they’re doing,” she said. “They’re drinking. They’re drinking alcohol.”

Still holding the boy, she turned so that his face nearly pressed against the next panel. Behind it was another diorama: Men and women carried babies up a staircase to the altar of a ziggurat, where a high priest was lifting a baby up toward a statue that loomed atop a throne. Swaddled in gold robes, this gorgon had the body of a man, but the neck of a python sprouted from between its shoulders, fangs bared, jaw nearly unhinged, orange light pulsating in its throat. “They was worshipping false gods,” Morgan said. “Y’all see the Snake God? That’s why God flooded the Earth, because everyone was being so wicked.”

Below the Snake God and the high priest, on the side of the dais, was a carving of a figure with wide hips and horns curving out from her forehead and sheaves of hair covering her breasts. Embossed on the walls alongside her, Egyptian-esque paintings of women in red and white and blue dresses were all holding up babies.

The woman with the pageboy said, “All those people are getting ready to sacrifice their babies. This is what they would do — take their babies up to the altar and sacrifice them.”

“Why would they do that?” the boy asked.

“Because that’s what they thought their God wanted them to do. They really had places like this a long time ago, and they still have places like this in some parts of the world.”

“They kill babies?” the boy asked.

“In America they do. It’s called abortion,” she said. “Look — they put the babies on the altar and burn them. We still do that today. Look at how corrupt—”

“It still is!” Morgan said.

“But we have Jesus!” the woman with the pageboy said.

“Oh, that’s true!”

“And the Holy Spirit!”

“That’s true, too!”

The final stretch of the exhibit was a mural of the flood toppling temples and false idols, sweeping away cities and palaces, while volcanoes exploded on a horizon charred with black clouds. Clinging to a precipice, people threw their arms out toward the Ark, glowing in the distance, buoyed from the last wreckage of civilization. In the bottom corner, a woman thrashed away from a shark that had half-swallowed her in its toothed maw.

“This is what happened when Noah entered the Ark,” the woman with the pageboy said, patting the little boy’s head. “The wicked people were unaware of the coming judgment, till the flood swept them all away.”

Cyndie and Robert Diber sat outside the Pre-Flood World, bouncing their two little girls on their knees. They were from Michigan but had been visiting family in Louisiana and came to the Ark on their way back — “to confirm what we’ve always read in the Bible,” Cyndie told me.

“We live in a culture where people are more emotional about their positions,” she said. “At heart, we’re all valuable to God. Whether I agree with who you vote for president or what your position on homosexuality is, you are as important as I am in the eyes of God.”

Robert said that he had seen protesters holding “Stop the Incest and Genocide Park” signs outside the Ark. “It’s their right to protest, but it seems a bit odd.” He shrugged. “Maybe they’re concerned that people are being lied to here.”

The group that had been picketing was the Tri-State Freethinkers, and a few weeks later I talked to one of the group’s founders, Jim Helton, who told me that Answers in Genesis had built the attraction “around a story about incest and mass genocide. We’re teaching kids that God murdered everyone, and this is the second time the Earth was populated through incest. It’s highly immoral.”

Other groups have leveled criticism at the Ark practically since its inception. A few years ago, Answers in Genesis applied for tax rebates through the Kentucky Department of Travel and Tourism, then under Democratic Gov. Steve Beshear. State officials were ready to grant the ministry $18 million in incentives, but withdrew after learning that a job posting on Answers in Genesis’ website required applicants to sign a “Statement of Faith,” “Salvation Testimony” and “Creation Statement Belief.” Answers in Genesis filed a suit, claiming that the ministerial exception of the 1964 Civil Rights Act permitted them to hire based on religious preference. “They sued the state for discriminating against them for not allowing them to discriminate,” Helton said. “It’s a clear violation of the separation between church and state.”

“People talk about the separation of church and state — there’s really no such phrase in the Constitution,” Ken Ham told me. “The Constitution and the First Amendment talk about the free exercise of religion, and what these secular groups are trying to do is eliminate Christianity from the public sector and the public schools.”

A federal judge sided with Answers in Genesis. By then, Kentucky had a new Republican governor, Matt Bevin, who announced that his office would not appeal the decision.

I wandered into an exhibit dedicated to the day-to-day practicality of running the Ark. Posters explained “Manageable Workloads” (“Each family member would have been responsible for an average of about 850 animals”); or “Smart Feeders” (“Food and water systems could have been used to contain several days’ worth of nourishment, allowing creatures to eat and drink whenever they wanted”); or “Waste Removal” (“Liquid waste could be drained away by a gutter system leading to an Ark-wide liquid waste reservoir”).

This last point I didn’t understand, until I came to the end of a hallway, packed with children standing next to their parents, all watching a TV that showed how the Ark’s waste-disposal system worked:

On an upper level, a man in a blue toga resembling a figure in an Etruscan frieze — one of Noah’s sons, I supposed — tipped over a wheelbarrow of dung, which tumbled down a tube and splattered into a pile that another Etruscan-esque figure shoveled into a huge, pulley-powered hamster-wheel, upon which an elephant plodded. The waste dumped into a chute that emptied into what Patrick Marsh told me was the “moon pool” — a chamber in the bottom center of a ship that allows seawater in, rising and lowing with waves without flooding the hull. The TV picture shifted to vats built in the roof of the Ark that collected rainwater. Another of Noah’s sons twisted a lever so that water gushed out of these vats and channeled into bamboo piping that dove down, fanning through the decks and linking to cisterns in cages that the animals drank out of. Meanwhile, another drainage network siphoned yellowish-green liquid away from the cages into the moon pool, which flushed into the ocean — flushing out, filling up, flushing out once again.

I drifted up to the third deck and into an exhibit that showed what Noah’s family’s living quarters might have been like. A poster (“Meet Your Ancestors”) divided Noah’s tribe into couples: Noah and Emzara, Ham and Kezia, Shem and Ar’yel, Japheth and Rayneh. These women go unnamed in the Bible, as Marsh told me: “Noah’s wife, Emzara, is a name often mentioned in extra-biblical writings. Kezia, Rayneh, Ar’yel are made-up names by us. We gave the wives different racial characteristics that foreshadow the development of the different races we see today.” Ar’yel seemed maybe Italian or Jewish, Kezia reminded me of a cinnamon-skinned African-American woman, and Rayneh looked cherubically Aryan. After the Flood, the poster explained, Ham and Kezia’s children populated “Africa and Asia,” Shem and Ar’yel went to the Middle East and Japheth and Rayneh settled Europe.

Chaises and chests of drawers adorned the living quarters. Papyrus scrolls crowded lattices. Strings of onions and peppers dangled from the ceiling. Towels draped along a rack, knives stuck into a block. What looked like an oaken shovel — a tool I imagined an ancient pizza maker might use to take dough out of the oven — was the centerpiece of one display.

“Their kitchen is so hipster,” a woman said. “It’s straight out of IKEA.”

I crossed the deck into a warren of exhibits that challenged scientific paradigms. “A huge problem for naturalistic thinking is its foundation in materialism — the belief that only matter exists,” the “Evolutionary Shortcomings” poster read. “However, morality, laws of logic and laws of nature are all non-physical. No one can swing by a grocery store and buy two ounces of logic, a bag of natural law, and a carton of morality. In a universe without laws of logic or laws of nature, how could anyone prove that naturalistic evolution has occurred?”

A man with silver hair pointed to a display about gravity while talking to a boy who looked like he was 10 years old. “Gravity has never been proven, because gravity is a large object attracted to a smaller object, and it’s never been seen. If gravity existed, a BB and a bowling ball should bump into each other. So you see how guys like Newton get caught in their own lies.”

Through the Ark drifted Amish or Mennonite families — men with ginger beards and flannel shirts, women pushing strollers, children flitting about in their calico dresses. I talked to a woman and her 20-something daughter, who were independent, fundamentalist Baptists from the Grand Rapids area in Michigan. The woman was named Cyndie; the daughter was Stacey — one of Cyndie’s 10 children.

I asked if the Ark was important to them. What purpose did it serve?

Her son Joseph said, “I think Ken Ham’s purpose for building the Ark is partially for Christ and partially for the lost world, because what the Ark does...”

“Sorry, what world was that?” I interrupted.

“The lost world — the world of unbelievers,” Joseph said. “Building this Ark shows the lost world that the Christian world is true and they need a redeemer. Just as this Ark saved the lives of Noah and his family and lots of animals, the lost world needs to accept Jesus Christ as their savior and their redeemer.”

I asked what they would say to someone who didn’t believe in the Ark story.

“Read the King James Bible,” Cyndie said. “Because faith cometh by hearing, and hearing by the word of God.”

After I thanked them for their time, Joseph said, “Just curious — where do you stand on all of this?”

“Me?” I said. “I’m a reporter. I just listen.”

The four faces blinked. Then Joseph repeated:

“But where do you stand on all of this?”

“Well,” I said, “I think we’re always learning from new experiences, and we are tiny and the cosmos is so much larger than we can imagine, and, the truth is, we really don’t know anything.”

The faces stared. Then Cyndie said:

“That’s where the Bible comes in. It has all the answers.”

There were no clocks on the walls of the Ark, and listening to the soundtrack of triumphal cymbals, I was reminded of the numbing placidity of dawdling for hours inside a shopping mall. I wondered if, for some Christians, this was a safe space where they could share their faith. So I asked a young couple, Jeremy and Sarah Strooksbury, why they came to the Ark.

They lived in Knoxville, but had taken a trip here with their church, the Eagle Bend Apostolic Church. “It’s cool to see a proportionate model of the Ark to help us understand the story better,” Jeremy said.

Sarah taught eighth-grade science, but she was skeptical of evolution. She told me that a new body of facts indicated that “a supernatural being created natural facts.” She went on: “There are irreducibly complex systems, like an eyeball, that evolve from this original, simple cell — how did they get there? Things can’t just pop into being. It doesn’t make sense.”

I asked if she taught evolution in her class. “I have to. It’s the law. They always tell me to give one answer: Natural law does not allow for a creator that’s supernatural, and God is supernatural. I can’t do a unit on the Ark in a public school, so I teach the curriculum. But I say, ‘Here’s what I believe. It makes sense that it would happen this way, too, just look at the facts.’”

Two scientists who worked for Answers in Genesis were meeting journalists on the third deck. The first scientist, Georgia Purdom, had received her Ph.D. in molecular genetics from Ohio State University. She now oversaw the Ark’s research in biology. Purdom told me that the larger scientific community considered the Bible to be myth because they started with a different viewpoint. I asked what that viewpoint was. “We believe it because the Bible says it, and because what we see in the world confirms it. We have a reasonable faith. Evolutionists have a blind faith. To them, if you include God in your reasoning, they rule it out. Because that’s not part of their belief system — and it is a belief system. People want to say that this is religion versus science. But it’s religion versus religion.”

The conversation drifted to the next stages of the Ark construction. Answers in Genesis had purchased 800 acres on this site, and they were planning “a Tower of Babel and a first-century village, just like Jesus would’ve lived in,” Purdom said. (Later, Marsh elaborated: “The Ark is just the introduction — we’re going to build a walled city next. It’s like a mainstream Disney, with streets and shops and entertainment places,” including an amphitheater for 35,000 people, sites that will house biblical artifacts, and a Ten Plagues ride.)

“So why an Ark?” I said. “Why build it at all?”

“We want people to see that the Bible is true,” Purdom said. “Just as there was a judgment in Noah’s day, there’s another judgment coming, and those who don’t know Jesus Christ as their personal savior will spend eternity in hell.”

Purdom introduced me to geologist Andrew Snelling, who followed Ken Ham to the U.S. from Australia and for the last nine years has been the director of research for Answers in Genesis. I said, “There were dinosaurs on the Ark, right?”

Snelling nodded. “Right.”

“Then why aren’t there dinosaurs today?”

“Dinosaurs went extinct after they left the Ark. After the Flood, we had the Ice Age. We had a radically different world. Some creatures weren’t able to adapt. But most cultures in the world have some legend about dragons, and these dragons are actually a good description of dinosaurs. The Chinese, for example — their dragons are depicted on scrolls pulling the chariots of emperors. And there was a story called Beowulf in which the king slays a dragon, and this happened in Norway.”

“So you take Beowulf to be evidence of dinosaurs existing?”

“Yes,” Snelling said. “It was an eyewitness account.”

I went down the last ramp and into a gift shop, peering at wooden staves priced at $22.99, earrings labeled “Fair Trade” ($9), Noah’s Ark 3-D foam puzzles ($6.99), bars of soap and bamboo flutes and Ark lunchboxes, a “Recycled Oil Drum Sculpture” of an elephant. I turned the tag twined round its ankle: $3,499.

The doors outside led to the end of the Ark opposite where I had entered, and I walked across the sun-struck gravel to Emzara’s Kitchen, a two-story roadhouse structure that resembled an amalgam of Cracker Barrel and an imitation Moroccan fortress. Inside, the first thing I saw was a hostess stand, and behind it a young woman in an Ark Encounter polo shirt tucked into black pants. She handed me a menu with items on it like “Noah’s Chili with Cheese Soup du Jour,” “Double Bacon and Cheeseburger — ‘The Two by Two,’” and “Pepsi, Mtn. Dew, Mist Twist ($2.50 – no refills).”

Along the perimeter was a dais on which stuffed nyalas and antelopes and bonteboks were positioned in attitudes of bounding. Mounted in one corner, a leopard pounced on a wildebeest. A stag commanded the middle of the room, crowned with antlers that almost grazed the ceiling.

At the back, teenagers in those same polo shirts flitted behind a fast-food-style counter. Fluorescent panels buzzed, shining on shelves of burgers and patties wrapped in foil and signs that marked off a line of stations. After I placed my order — the jalapeño chipotle burger, with a side of Noah’s soup du jour — the girl behind the register handed me a paper bag with my food in it. “Should I slide my card?” I said.

“Yeah, it doesn’t read chip. And I’m going to press this.” Leaning forward, she tapped a box labeled “No” on a screen that asked what tip I wanted to leave.

“You don’t want a tip?” I said.

“We can’t accept tips.”

“Why not?”

“We’re a nonprofit. We work for God. He blesses us.”

“Hey, just curious,” I said, “how much do you all get paid?”

“I’m not sure, because I’m part-time, but I think most people get $9, $9.50,” she said. “When they finish the whole Ark Park, it’s supposed to be more like Disney, and then you’ll be able to leave tips.”

The second level of Emzara’s Kitchen was empty, and I ate my food and left again, wandering back to the grassy hillock in front of the Ark, inside which was a basin of water that reminded me of a fishing pond in a farmer’s back pasture.

Nightfall was hours away, but already dimness thickened the air. Scarves of blue mist unfurled in the pockets and hollows of the forest that dipped below the plateau. The woods appeared untrammeled, almost biblical. Yet the ground around me was upturned and soggy. The pond looked gray and flat as a tarmac.

From this stance, I could see the Ark in its entirety, and it seemed slanted, as if one end was tipped up higher than the other. I stared at it. Then, closing my eye, I stretched my arm out and cocked my finger against my thumb, and flicked — imagining that I sent it spinning across this latter-day Ararat like a dreidel.

A few days later I drove to the Creation Museum, about 50 miles north of the Ark, in Petersburg, Kentucky, off I-275 and tucked behind the Cincinnati airport.

Posters hanging in the front hall affirmed what Snelling had told me — human cultures have lived among dinosaurs in the form of dragons. A display with a warrior’s helmet propped on a stand, the scrap of a scroll upon which had been scratched Tolkien-like runes, and a sword crusted with blood, was headed: “Beowulf and the Dragon”: “Aided by a brave warrior, Beowulf vanquished the flying dragon and saved the land. Did these men or their ancestors actually fight dinosaurs and pterosaurs? This idea would be consistent with the Bible.”

I went into the museum, finding myself in a brick alley drowned in red light and splattered with magazine clippings (“Mass. Opens Doors…To Gay Marriages”; “The Fall of Christian America”; “Is America Going to POT?”). Then a re-created Garden of Eden, after which a sign proclaimed “Sin Changed Everything” in a room of posters — the Hiroshima mushroom cloud, an African child with his ribs stenciled out, a man shoving a needle into his arm. And then a gallery of Adam and Eve’s world after they sinned: shacked up in a cobblestone bungalow, Adam with shaggy hair and a dad bod, Eve pregnant again, a couple of kids tugging carrots out of the ground. Twenty feet away, an animatronic velociraptor emitted high-pitched calls of bloodlust.

I kept walking, out of this gallery — and then I saw it, again: the Ark, or at least the Creation Museum’s exhibit on it.

The room before me soared like the set of a movie studio. The centerpiece was a multi-level matrix of platforms and railings buttressed in front of a wooden wall — one of the sides of the Ark under construction. A cacophony of saws and hammers churned the air. The stone floor I followed led past two animatronic figures standing next to a table strewn with papyrus documents. Both were men. The older one was Noah.

Rocking in place, with his arms emerging out of the folds of his sleeves, he was holding a tablet and what looked like a pencil and saying to the younger man: “You need to have a look at that new shipment of planks and make sure the treatment was done as we told them. By the way, my friend, have you thought about our conversation? God’s Word is true.”

Suddenly he called toward the boat: “Hey, Zophar! Were those pegs checked by Shem before you sawed them off?”

Back to the younger man, voice softening: “Judgment is coming, my friend. But if you come along, you will be safe in the Ark.”

Below the railing where I stood, three other animatronic men in tunics and earthen-brown caps were sitting together cross-legged. One was saying:

“What a fool! Why does he believe the Word of his God? We have been working on this boat for years and not a drop of water. This talk about the Flood is ridiculous! Every day, the same, same, same!”

Then the man spat: “He is a religious fanatic!”

This originally appeared in the January 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find your very own copy of Louisville Magazine, click here.