About these photographs: Since 2015, photographer Andrew Cenci has been documenting life in Shelby Park. “It happened to be where I lived,” he says, “and I wanted to try shooting on film. I found so much inspiration in the neighborhood and kept shooting.” Cenci uses black-and-white film, including for the medium- and large-format portraits he has been taking of residents in the park and inside their homes. His hope is to create a book. “About two years ago, this started to feel more like a project, less like just going and shooting,” he says. For this story, Cenci also shot the digital photos of Ann Ames and Chip Rogalinski.

Data journalist Joshua Poe contributed data analysis.

It’s easy to meet people in Shelby Park. On a warm day, neighbors collect on front porches or landscape the snug rectangle wedged between their front door and the sidewalk. No wide carpets of grass here. No retreating behind privacy fencing for social hour. This isn’t the suburbs. About 3,300 residents fill a compact, orderly grid of streets that act as a thick frame to a 16-acre park, a communal backyard with enough of a tree canopy to humble winds roaring past nearby I-65 or downtown or somewhere east into a whisper of a breeze.

It doesn’t take great effort to connect with neighbors. That’s how it’s always been, long-timers say. And years ago, it wasn’t uncommon to have one family — grandmas, aunts, uncles, cousins — divided among three or four houses on a single block, children often parading to and from the former St. Vincent de Paul elementary school on Shelby Street that closed in the late ’80s.

According to four-year-old census figures, median household income in Shelby Park was just over $19,000, and nearly half of residents in the neighborhood lived below the poverty line. Nearly 80 percent of households were renters and eviction rates were (on some blocks) as high as six times the national average. Despite being small, Shelby Park has routinely tallied 200 to 300 drug-related crimes every year, and many neighbors expect to hear occasional gunshots in the park.

Today, stand anywhere in the neighborhood for just a moment. You’ll likely hear a saw buzzing or spot someone crawling up a ladder to strip siding. Big-bellied green dumpsters dot the neighborhood. “We Buy Houses” signs pop up on telephone poles, though some here make a hobby of ripping them down, worried those investors will recklessly swoop in and out for quick money. Because here’s another thing you’ll hear in the neighborhood: “Shelby Park is on fire.” I hear it from real estate agents and developers, even a few residents. “Investors are in acquisition mode,” one agent says, mentioning a shortage of move-in-ready homes in the city’s urban core. That’s what many young families and singles want.

One house in Shelby Park recently sold in six hours. This old neighborhood — sandwiched between Smoketown and Germantown and shaped a bit like a gumdrop on its side — has the right bones. One developer who bought a 1,300-square-foot house on Camp Street in 2017 for $56,000 recently put it on the market for $209,000. Another developer picked up a 1,100-square-foot property for $24,000 on East Ormsby in 2017 and one year later sold it for $160,000.

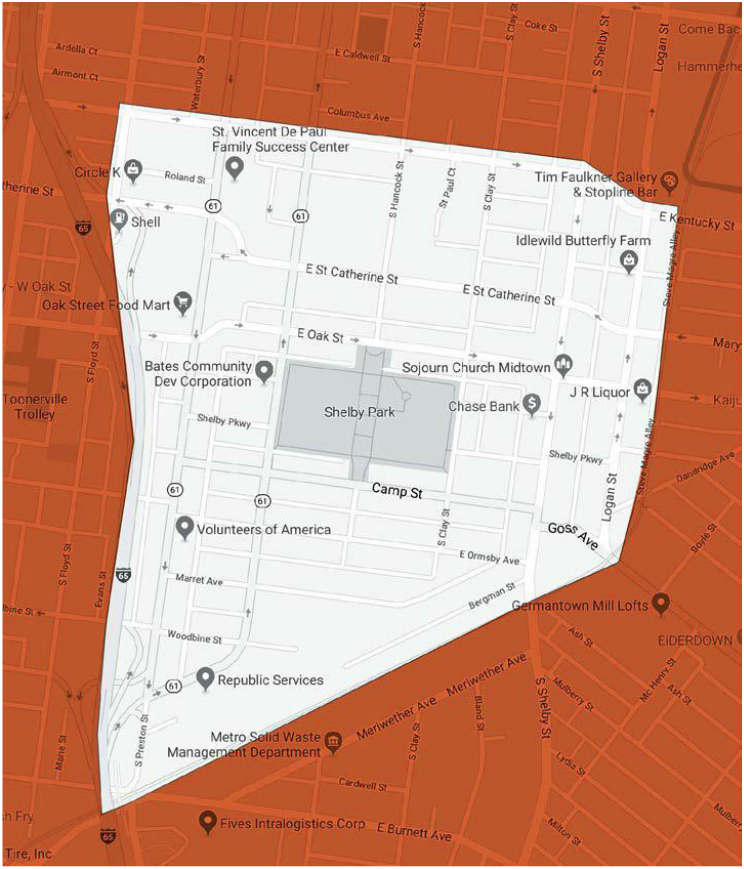

|

| Shelby Park neighborhood boundaries. Click here to expand. |

Empty storefronts that once housed carpet and appliance stores, a motorcycle repair shop or nothing at all now host a co-working space and a coffee roaster, and a bourbon bar is on the way. An old candy and tobacco warehouse will soon debut as the year-round Logan Street Market, with 30 vendors including a cheese shop, bubble tea shop, and a brewery, plus restaurants and a small market with produce and a few household staples.

According to data from the Jefferson County Property Valuation Administration, the median property value in Shelby Park has gone from about $74,000 in 2015 to $123,000 in 2018, a 67-percent increase.

Shelby Park has long been a neighborhood with impressive racial diversity (considering Louisville’s mostly segregated neighborhoods), with about one-third white and two-thirds African-American as of the 2010 census. The 2020 census will capture how much of a shift Shelby Park has experienced in recent years. But data from the American Community Survey show that between 2010 and 2017, population in Shelby Park grew by 21 percent. The white population rose by 40 percent. The black population dipped by 2 percent. (White households now make up about 40 percent of the population, with black households totaling 51 percent.) Married households increased by 60 percent.

One afternoon I meet Ron Bailey, a 45-year-old, 6-foot-8-inch former college basketball player who grew up in the neighborhood in the ’80s and ’90s. He points to the park a few blocks away. “That’s where I made my name,” he says, referring to his years playing on the court there. Bailey now lives in Louisiana but on this day is back in Shelby Park catching up with his mom and cousin on his mom’s porch. He sips a Bud Ice and says that Shelby Park still feels like home, though it has changed. “Don’t take this the wrong way, but it seems like there are more uppity white folks moving in,” he says. “I thought of this as the ’hood growing up. Not in a bad way. The ’hood is beautiful.”

His mom looks at him sideways. “My neighbors aren’t uppity! I love my neighbors,” she says, referring to the newcomers who surround her.

“It just seems like people who may have only come to Louisville for Derby are now moving in,” Bailey says. (“More upper class” is how another resident put it.)

Bailey’s cousin, who also grew up in the neighborhood, stares out at the tree-lined street. “Well, I think that’s a big accomplishment,” she says, adding a proud nod.

For nearly three weeks, I walk the neighborhood. “It’s a beautiful place,” a woman with silvery-blond hair says one afternoon, raving about the maple trees in the park that rust gloriously come autumn. And don’t miss Oak Street during Derby season, when the dogwoods christen spring in pink and white. In the mornings, a burnt-toast smell visits, likely from a neighborhood coffee roaster. And after a rain, on the west side of East Ormsby, a phantom “cat pee” smell arrives. Nobody — not MSD, not the Air Pollution Control District, not LMPD — can crack the mystery.

I talk to more than 30 residents. There’s excitement, a feeling of: It’s about damn time. In 2010, the number of vacant homes in Shelby Park totaled close to 400, with about a third of those considered “vacant and abandoned” due to neglect and dangerous conditions. A few of these properties remain magnets for squatters. One ivy-clad home on East Ormsby shelters a family of raccoons. “Everyone’s always talking about fixing up the West End,” one woman tells me, thankful to see revival in Shelby Park. This transformation likely traces in part to Germantown’s boom. As prices soar there, interest spills over the railroad tracks and into Shelby Park. In neighboring Smoketown, the renovation of the Sheppard Square public-housing complex into mixed-income housing has created its own orbit of activity.

What’s happening here — in Shelby Park, in Germantown, perhaps soon in Russell in west Louisville — is occurring all over the country: Once-thriving neighborhoods — which experienced significant disinvestment due to white flight, urban renewal or the intrusion of an interstate — are popular again.

Gentrification. There’s the word, one that’s used so much the meaning has either been diluted or complicated. “Gentrification describes a problem of neighborhood change,” says Kelly Kinahan, a professor with the University of Louisville’s Department in Urban and Public Affairs. “Wealthier people moving into lower-income, non-white neighborhoods in particular. It describes a process, but being able to say this is (gentrification) and this isn’t is much harder. There’s no hard, fast line.”

Shelby Park’s worth, the rock and dirt on which it sits, and a foundation up through a roof, is on a steep ascent. A square foot of home in Shelby Park was valued at $63 in 2016. By 2018: $95. “This is an anomaly like what Germantown experienced,” one realtor told me. Talk to renters; they’ve had to adjust. Median rent as of 2016 was $500 to $600. It’s nearly impossible to find any place in Shelby Park with rent that low now, I’m told repeatedly.

One evening, I meet a woman who works third shift at the main post office on Gardiner Lane. She cradles her infant grandson and watches her friend’s grandson play samurai with a stick. She rents with her friend, though the landlord plans to sell his property when the lease ends. “We’ve been looking around the area. The house down there,” she says, pointing to a shotgun down the street, “I called and it was $799 (a month). It’s a one-bedroom. There’s no off-street parking. I didn’t see a whole lot of amenities. This don’t make sense to me.” She says she’ll probably look in the South End. (I did speak with a handful of renters who have not endured any rent increase in years.)

Some in Shelby Park are adamant that gentrification is not happening. They point to sincere efforts by the Shelby Park Neighborhood Association (SPNA), a group that has partnered with and even recruited nonprofit developers into the neighborhood so that homes can be renovated and sold below market rate. And the neighborhood association has made a commitment: While it wants homeownership to increase in the area, especially in empty, aging homes, it also wants the neighborhood to remain at least 50 percent rental properties.

Another evening I meet Robert Bell at a neighborhood association meeting, tucked in the bare basement of what 100 years ago was a library, then a community center and now, mostly, a gathering spot for meetings and a twice-weekly afterschool music program. Bell moved to the area with his family four years ago. He likes to share this anecdote about SPNA’s mindset: For the last few years, they’ve organized a Renovation Expo and Open House, a way to showcase the neighborhood with tours and workshops. As part of the event, SPNA wanted to include House of Ruth, a Shelby Park-based nonprofit that provides services to low-income individuals with HIV and AIDS. They also invited the Volunteers of America family shelter on Preston Street to have a presence.

Bell says he and another SPNA board member were talking to the vice president of a prominent bank about the event and that she paused at the mention of VOA and House of Ruth. “She said something along the lines of, ‘Are you sure that’s how you want to represent your neighborhood?’” Bell recalls. “And we said, ‘These are our neighbors. This is what we take pride in. If people have problems with that, we don’t want them to live here.’”

German immigrants settled Shelby Park in the late 1800s. In the early 1900s, then-Mayor Paul Barth noted that a large number of families with men working in nearby factories, including the Hillerich & Bradsby Co. Louisville Slugger factory, had no place convenient for recreation. The city bought 17 acres from the Caldwells, a wealthy family with ties to European royalty. (Street names in the area — Gwendolyn and Caldwell — nod to the family’s legacy.) The firm founded by Frederick Law Olmsted designed the park.

Neighbors each donated $2 to purchase land for a Carnegie library that opened at the north edge of the park in 1911. Track meets brought hundreds of spectators to the neighborhood park. Tennis courts were popular, as was a large circular pool built by the War Recreation Board for soldiers at Camp Zachary Taylor. (Old Courier-Journal articles document “Body Beautiful” contests at the pool and a shortage of swimsuits for rent because crowds were so large.)

Shelby Park remained solidly working class for decades, with families living in Queen Anne-style and shotgun houses. In the 1930s, Shelby Park and nearby Smoketown were hit with redlining, the practice of denying loans in a neighborhood due to its racial and socioeconomic makeup. Back then, the Home Owners’ Loan Corp. (HOLC) created maps with shades of various colors depending on what HOLC determined was their strength for investment — red indicating the worst areas. A HOLC document for Shelby Park and Smoketown lists that 20 percent of the population were “Negros” (an undesirable characteristic according to HOLC). Other detrimental influences in the area: industrial plants, saloons and a city incinerator. Longtime residents remember that garbage incinerator. One woman says soot would cover her car and home some mornings up until it closed in the ’90s.

Redlining made it difficult for residents to secure mortgages and mortgage insurance. Many white families headed east. And so the segregation of Louisville grew. That Shelby Park remained a mix of white and black residents may be due to its location, at the confluence of largely white Germantown and predominantly black Smoketown.

Over the decades, older residents passed away and homes sat in limbo. By the ’80s and ’90s, plenty of drug dealers were openly selling on street corners. Prostitutes claimed space on Preston Street and shootings in the park multiplied. Maintenance at the park deteriorated. (Some complain grass is still way too high, way too often.) The circular pool that had long-since closed made way for another pool, affectionately known as “Big L” because of its shape. That also closed, in 2007.

The people who have lived in Shelby Park during the last half-century are a sturdy, loyal lot. They formed an active neighborhood association that managed to fight off a proposal by the city in 1999 to turn the old library into a school, which would have effectively cut off half of the park to residents. Betty Kolb was secretary of the neighborhood association in the ’90s and early 2000s. She and her parents moved to Shelby Park 40 years ago, no matter the naysayers of the time. “People who lived in Germantown thought we were the West End,” she says. Kolb, who on the day we talk is watching her pigtailed granddaughter bounce around the park, has this final thought: “It’s the place to live. Highlands are there, Germantown there, Old Louisville there,” she says, one arm swiveling like a compass. “I’ve known that since 1975.”

The Shelby Park Neighborhood Association has a partner, “a marriage,” I’m told, with New Directions Housing Corp., a nonprofit affordable-housing developer. On a sunny morning, I meet Max Monahan, the group’s assistant director of homeownership preservation, in front of a brick camelback that New Directions is renovating. Its guts are shredded but by mid-June it will charm: a stained-glass transom window, glistening hardwood floors, refinished pocket doors in the front room.

New Directions recently purchased eight properties from a Louisville man, Michael Meyer, who bought about a dozen properties in Shelby Park in the ’80s and ’90s. Meyer tells me he had plans to renovate them but “never got around to it.” Many of his properties have stood vacant for years, deteriorating. One had a renter that Meyer asked to move when the deal with New Directions was secure. Of the eight properties, one was sold to another nonprofit developer, four will be sold at market rate and three will be sold slightly below market value and reserved for a buyer who makes 80 percent of the area median income or about $43,000 a year. (After five years, the deed restriction designating the home for a buyer at 80 percent AMI expires and anyone can purchase it.) What “slightly below market rate” translates to: A 1,050-square-foot New Directions home in Shelby Park recently sold for $130,500. (By comparison, a slightly larger house down the block sold at market rate for $160,000.) A 1,400-square-foot shotgun renovated by New Directions sold at below market rate for $145,500. (Profits made by New Directions go toward other affordable developments.)

Recently, Metro Government commissioned a housing-needs assessment, analyzed how much affordable housing the city lacks. (Cities nationwide are experiencing a similar affordable-housing crunch.) The study found that individuals who make $43,000 — or 80 percent of area median income — required about 4,400 units to meet demand. For households earning about $27,000 or less, Louisville is in need of 50,000 units.

Monahan explains that building very-low-income housing is tricky, often requiring layers of funding from grants, the government and even foundations, so that the cost of building and maintaining can be subsidized to the point of affordability. No surprise: Less and less money is available for such projects.

Monahan and I drive around Shelby Park. We go past the Jackson Woods apartments, a bulky New Directions complex dating to the ’70s that offers rentable housing to low-income earners. Right now, though, Monahan says, New Directions is focusing on homeownership in Shelby Park. That’s the group’s charge, given that only about 23 percent of neighborhood residents own their homes.

We head to St. Catherine Street to look at homes New Directions renovated in 2010. (New Directions has renovated a total of 18 properties in Shelby Park.) Monahan pulls in front of a brick, two-story home with a tidy front lawn. “We did six homes here on this block — two vacants, two burnouts, two empty lots,” he says with play-by-play excitement. At the time, the federal government was freeing up money under the Neighborhood Stabilization Program in an effort to combat the recession. Had those dollars not been available, and had New Directions not committed to the effort, Monahan says this block of St. Catherine would’ve likely stayed blighted. “The private sector would’ve never done it. There’s no money to be made,” he says. “Someone’s got to bite the bullet and take on major projects.”

We drive past a vacant house New Directions is fixing up known as “the castle,” a fairytale of a home on Camp Street with a stone facade, arched doorways, a swaying weeping willow and boarded-up windows. We pause at a bulky bluish-gray home on Oak Street that’s still being built. It’s size and design — privacy fencing, detached garage, wide front porch — stand out among Shelby Park’s mostly older, smaller homes. “Seven years ago if you would have told me that there were going to be new construction on Kentucky or Oak, I would’ve thought you were crazy,” Monahan says. “All of a sudden, the private sector is all over the place, which is a good thing. It means we helped create the market. Before, it was basically a broken economy where you couldn’t have gone in there, bought a house, fixed it up and sold it without losing your shirt.”

Many say they moved into Shelby Park because it’s what they could afford — a logical decision. Somewhere along the way, momentum followed and others caught on. Longtime residents quickly took notice. “Three or four years ago, everyone started fixing up their house. I was one of the only ones with flowers and plants. Now everyone else is planting too,” a nearly 80-year-old woman tells me, tenderly saying, as if sharing a secret, that some of the renters who have moved out in the last few years were “just sort of trashy.” One business owner put it more bluntly: “The shit is moving out, the good people are moving in.”

One evening in the park, I meet Noel Deeb, a stay-at-home mother of four whose children play as if powered by the sun overhead. A member of Sojourn Community Church, Deeb is among a wave of church members who moved into the neighborhood about seven years ago, when Sojourn completed a $3.5-million renovation of the St. Vincent de Paul parish that closed in the early ’90s. “We are literally calling members of our congregation to move . . . and engage the neighborhood residents into deep relationships,” a former Sojourn pastor told WAVE 3 News. Deeb and her family actually pre-dated that call, moving in more than 10 years ago. She and her husband were baristas at the time, and Shelby Park, she says, was “what we could afford.”

The beginning was tough, Deeb recalls. “When we first moved here, we were held at gunpoint in the backyard. Our house was broken into,” she says, adding that, over the years, “We’ve known people who were murdered on our street.” Things are quieter now, she says. “Which is good, but it’s sad to me,” she says. “I’ve seen a bunch of our neighbors kicked out, people we’ve made relationships with have disappeared.” During my time in Shelby Park, I meet three other residents who say their family or friends have had to relocate as property owners opt to sell, giving renters a 30-day notice to vacate or face eviction court. “It will be interesting to see what happens in a few years,” Deeb says. “Is everyone going to be gone that used to be here?”

If Mary Ann Nichols has it her way, the answer is: not over her dead body. And then even after that. She wants to write in her will that her home on Shelby Parkway can’t leave the family. Nichols, in her 70s with a plume of white hair and a quick wit — “I’m old. I don’t need anything but a roof over my head and a sandwich” — has lived here for 32 years. Walk into her modest brick home and get comfy. She has dedicated a mantle to her twin boys and daughter, whom she raised mostly as a single mother. She’s proud, with plenty of stories to prove why.

As we’re talking one day, she mentions that she’s surprised her phone hasn’t rung. She gets frequent calls from investors, text messages too. She gets fliers in her mailbox and knocks on the door. I hear this story from many older residents. A couple times, despite identifying myself as a writer, residents remain suspicious. “Are you part of a land-management company? Do you flip houses?” one man holding a small dog in an infant onesie asks me. Nichols, who spent years working at the phone company, is fed up. “We feel like they’re trying to run us out, and we don’t like that piece of it. I’ve told my kids not to sell this house,” Nichols says. “I’ve struggled too hard and too long . . .I don’t care what you do, but don’t let this get out of this family.”

It’s a sentiment Barbara Smith shares. One afternoon she invites me to her brick courtyard, a space fit for gnomes. There are stacks of clay planting pots, an antique table and a gaggle of cats fiddling under a tree that offers protective shade, a leafy hoop skirt to those below. Smith, who is 68, moved to the neighborhood about four years ago with her daughter. Smith was heavily involved in the pre-NuLu renovation of East Market Street back in the ’80s, along with Billy Hertz, a well-respected artist and fellow Shelby Park resident, having relocated his gallery and home to Preston Street in 2008 once, as he puts it, “too many ladies from the East End” started poking their heads into his gallery and posing inquires like: “Do you have any pretty things here?” Over the decades, Smith watched as what she’d hoped would be an arts district on East Market turned into something trendy and retail-y. She says longtime residents moved on to make way.

A few years ago, Smith regularly noticed an old, weathered man shuffling down her Shelby Park street to JR’s bar. He’d buy a candy bar and a beer and shuffle home. “He struck me as the kind of person we don’t want to force out of the neighborhood,” Smith says. JR’s closed last year. Many neighbors cheered, citing frequent violence there. The developer, Chris Thomas, who bought the building along with the duplex next door, hopes to bring a family-friendly restaurant to the space (maybe “tacos or street food,” he says) and adds that he gave financial assistance to tenants who moved out of the apartments located in the buildings.

Smith still wonders what happened to the old man, whose daily commute ceased. Perhaps he’s no longer around. “You know, how people make money intrigues me endlessly,” Smith says, pausing. “Why am I opposed to people making money off this neighborhood when all commerce is based on that same premise?” She offers an example: Someone goes into Walmart, buys a toy; someone makes money off the sale. Why does it feel uncomfortable when the equation involves people and property? Real estate has long been the greatest way to build wealth. (In Louisville, 70 percent of white households own their home, compared to 36 percent of black families.) Smith sighs, still pondering the tension. “It’s something I just haven’t figured out yet.”

There’s no single catalyst that ignited Shelby Park. But Sojourn Community Church’s move from Germantown to Shelby Park in 2012 marks a pivotal moment. One morning I meet a Sojourn pastor named Nathan Sloan at the church. The marble and statues of St. Vincent de Paul have left, making way for a drum kit, amps and art that reflects biblical themes. In the lobby, Sojourn’s mission is brightly painted in yellow and orange: Reach people with the gospel. Build them up as a church. Send them into the world. Sloan says Sojourn’s decision to move to Shelby Park was partly due to its desire to become more ethnically diverse. “Show the beauty of all God’s people,” he says. By his count, about a dozen families chose to relocate to Shelby Park when the church moved in an effort to “love and care for their neighbors.”

Sojourn, which is a Southern Baptist church, hosts free medical and dental clinics, as well as neighborhood festivals. Sloan says Sojourn’s membership hasn’t grown drastically since moving to Shelby Park (about 1,400 across three Sunday services), but the impact is felt. Betty Kolb says the first few times she saw families trekking to church, it dusted off memories. “It reminded me of when I was little because we all belonged to St. Vincent’s,” she says.

Sojourn isn’t the only church in the neighborhood, not even the only Baptist church. So maybe it shouldn’t catch my attention when a resident who has just finished a bike ride with his kids tells me he loves Shelby Park because, “We’ve felt the light of Christ here.” Erin Hinson, a Shelby Park resident who was the legislative aide for former Metro Councilwoman Angela Leet, says that after sitting through endless city meetings, she decided that government could only do so much to remedy crime and vacancies. So she packed her two young sons and husband to move from St. Matthews to Shelby Park. The family rents but plans to buy. “Improvement requires neighbors loving neighbors,” Hinson says. Sometimes that means mowing a neighbor’s lawn or offering mischievous teens snacks and a chat instead of calling the police. Hinson’s mom describes her daughter’s Shelby Park journey as a “calling from God.”

A few years ago, Sojourn recruited missionaries to live and work in Shelby Park, and some have decided to stick around long-term. That program grew into its own nonprofit separate from the church. Sojourn’s lasting legacy may lie in its ripple effect, in its members who have started their own Shelby Park-based organizations, the biggest being Access Ventures Inc., a nonprofit created by former Sojourn pastor Bryce Butler. Started in 2014, Access Ventures has invested in 14 residential properties (including six apartments) and four commercial properties. “AV,” as Butler calls it, has a wide portfolio, with stakes in everything from micro-lending to blockchain crypto currency to companies that seek to provide socially conscious investing opportunities. Butler says any returns on investments go into an endowment for ongoing projects.

Access Ventures has provided hard-to-get small business loans to Shelby Park businesses like Idlewild Butterfly Farm, Good Folks Coffee and Scarlet’s Bakery, a bakery opened by a Sojourn member with the mission of providing jobs and skills to women working in the sex industry. Without Access Ventures, Shelby Park’s commercial corridor would look far different. Headquartered on Shelby Street, Access Ventures has also opened a co-working space called The Park and has paid for neighborhood murals, including one that reads: Shelby Park: Building something bigger than ourselves together. Commercial investment beyond Access Ventures is picking up, with places like Logan Street Market coming soon and Tim Faulkner Gallery moving to Shelby Park from Portland last year.

Access Ventures has intentionally slowed the real estate side of investment in Shelby Park. (It has sold three homes and still owns rentals.) Its focus is to analyze what impact the investments have had in Shelby Park. “The response to gentrification is not: Let’s not do any development,” Butler says. “It’s: Let’s do it at a pace so that residents can participate in the improvement in the community.”

In 1963, at a bakery on Shelby Street that shuttered long ago, Ann Ames met her husband. It was November, the week before JFK was assassinated, and there in a booth was Ed Ames, a friend of a friend. She was 19, too nervous to eat. “You don’t eat a doughnut in front of someone you want to impress!” she says with a smile. Six weeks later, the two got married. Three years later, they bought a brick camelback house on Camp Street from the aunts of Victor Mature, an actor famous in the 1950s. “I’ve lived here 52 years,” the 74-year-old says, leaning on the armrest of her living room couch. “For me, this is the best neighborhood.”

|

| Shelby Park resident Ann Ames. |

The mother of five children worked in JCPS for 38 years, mostly at Meyzeek Middle School, about a mile from her home. Ames’ role as “home school coordinator” required helping kids and families with any issue that might impede learning. She helped bury parents, arranged for medical care and clothing, even drove kids to and from Myzeek, a few middle-schoolers collecting on her corner religiously in the pre-dawn gray light.

When Ames and her husband moved into Shelby Park, the neighborhood had a no-frills sensibility. There was a small market, a clothing store and pharmacy over on Shelby Street. Her neighbor would wake early every morning and have her kids’ fresh laundry drying on the line by 5:30 a.m., then straight to the corner she’d go to catch the bus to her job at a factory in west Louisville. Some of her other neighbors worked as school cafeteria cooks and at hotel front desks. Across the street in a small, dark-brown apartment building (Access Ventures now owns it), Ames would watch a woman meticulously wash her windows every Saturday.

After 52 years here, Ames can’t recall a specific timeline of when the neighborhood changed. It’s scattered memories — deciding never to return to the park in 1970-something after being called a “bitch,” lying on her living room floor as a SWAT team raided apartments across the street in 1980-something. Mostly she remembers her former students and their difficult lives here in the ’90s and 2000s. “They can break your heart or fill you with pride,” says Ames, who retired three years ago.

She knew Troya Sheckles, a witness in a murder trial who, at age 31, was shot and killed in Shelby Park. “She was a good girl,” Ames says, sadly. Two of the boys Ames always drove to school ended up in prison for killing someone. So when Ames says that she doesn’t “see as many kids walking around with red bandanas because, you know, this is Blood country,” it’s a real observation.

Violent crime and robberies have decreased over the last three years. After a record seven murders in 2016 (a particularly violent year citywide) there haven’t been any murders since 2017. LMPD Major Josh Judah, who oversees Shelby Park and surrounding neighborhoods, says the decrease in crime is a result of more targeted policing, an effort to lock up the “worst of the worst.” Drug crime remains high, but Judah says it’s not disproportionate to other inner-city neighborhoods in his division.

After decades spent avoiding the park just down the street, Ames has started visiting again, often with a few of her 16 grandkids. It’s a lovely benefit of progress. It even softens the blow of her property taxes rising from about $200 to $500 annually in the last five years. She tries to keep track of families shuffled by the revitalization of Shelby Park and Smoketown. “A lot of them live out by Churchill Downs now,” Ames says. Her husband died at home this past fall after 55 years of marriage and a long struggle with pulmonary disease. Neighbors, old and new, fed her, prayed with her, hugged her. It’s hard living alone. But she can’t imagine detaching herself from Shelby Park. “I’ll be going out the way Ed did,” she says. “Out the back, down the ramp and into Bosse’s (funeral) car.”

In my time in Shelby Park I am asked, “Have you talked to Chip?” at least a dozen but maybe 100 times. As president of the Shelby Park Neighborhood Association, those who know Chip Rogalinski describe him as “Mr. Shelby Park,” and as a “force of nature.”

His M.O., in brief: Gather involved neighbors, bundle all the goodwill, push, push, push and voila — this place looks a lot nicer! Plant 500 trees in five years? Done. Ask Metro Councilwoman Barbara Sexton Smith to get eight of those $600 iron trashcans with the neighborhood’s name on them? Check. Pole banners? Yes. Historic markers? Let’s get four or five. Next? How about an elegant entrance to Shelby Park?

Rumor has it that Rogalinski convinced Mike Safai, an entrepreneur and owner of Safai Coffee, to go through with the Logan Street Market, in the space that was originally going to serve as Safai’s roasting headquarters and a beer hall. Rogalinski and neighbors also helped influence the decision to include a weekly farmers’ market, where low-income customers can pay what they can afford for fresh food. (Save-A-Lot closed abruptly last fall in Shelby Park and several residents voice to me the need for a grocery within walking distance.)

Chip Rogalinski, aka "Mr. Shelby Park."

Rogalinski spent his childhood mostly in the South End, and when he bought a renovated shotgun (“My shotgun mansion,” he calls it) eight years ago in Shelby Park, he says he didn’t know much about the neighborhood. A fan of Billy Hertz, he liked that the gallery was nearby. “My parents thought I was crazy,” he says with a smile. “They didn’t see the value in it.” They do now. Vacant properties have decreased to about 200. New walkways and play equipment were added to the park this year.

Rogalinski is an empty-nester, only two dogs — Halen (as in Van Halen) and Sahara — with him. He has thrown himself into the neighborhood for the last seven years, officially and unofficially. “We want this to be the epitome of a true, blended neighborhood,” he says. He connected House of Ruth with River City Housing, a nonprofit housing developer, and urged along a project that’s under construction on Kentucky Street — a duplex that will rent to low-income men and women with HIV or AIDS.

Rogalinski recruited River City Housing into the neighborhood by taking its executive director, Becky Roehrig, on a walking tour a few years ago. (He adores walking tours.) River City has plans to work on a total of five properties in the neighborhood. Roehrig says her goal is to ensure Shelby Park residents — those who earn 80 percent of the area’s annual median income or less — can move into River City homes. This summer, a woman who has rented in the neighborhood for years will take part in a federal homeownership program that permits her Section 8 voucher to go toward mortgage payments. When the five houses are complete, Roehrig says that will likely end her group’s time in Shelby Park. Acquiring properties is near impossible these days. “We would probably get out-bid,” she says. “So that’s why it’s important that what we are working on in Shelby Park goes to people in the neighborhood.”

Blending old and new is tense work — not fights-and-snarls tense, but gut-check tense. Perhaps that’s why the suburbs appeal to many, all easy living and uniformity. At a recent Shelby Park Neighborhood Association meeting, the issue of neighborhood kids riding dirt bikes and scooters in the park is discussed. Extra police patrols might help, it’s suggested. A few at the table lean in, worry scribbled on their brows. Could this lead to juveniles getting slapped with disorderly-conduct charges? “This is their park too,” a young woman says.

Shelby Park is in Louisville, a place where change inches along. The neighborhood won’t erase as we know it. But Rogalinski and others are concerned about Shelby Park’s designation as an Opportunity Zone, a 2017 federal program that incentivizes investment into poverty-stricken areas with large tax breaks for investors. (Access Ventures is part of a national bi-partisan group working with legislators to create Opportunity Zone regulations.) Rogalinski believes guidance and limitations are necessary to ensure investors don’t go Wild West on Shelby Park. Kelly Kinahan, the U of L professor, wonders, “Who is going to benefit from the tax breaks associated with the program, beyond the super-wealthy making the investments?”

Rogalinski emails me in mid-May. The first line reads: This does not seem to be the managed growth we seek . . .

I open a link to a real estate blog that lists the top five “hot” Louisville neighborhoods. Number one? You guessed it: Shelby Park is “smoking HOTT!” a realtor writes, adding that it “has become an investor’s gold mine…Want to know the profit investors are making? A house located on S. Shelby St. was purchased last year for just $60,000 (an AMAZING mortgage payment btw) and it sold this March for $220,000! Not only is this a hot area for flips, it’s also becoming a popular neighborhood for AirBnB.”

Rogalinski writes: My personal reaction? Never thought I would see this day…

He goes on to stress that many of the renovation efforts underway by nonprofit developers are saving historic homes that would likely end up demolished if untouched.

How do you not try to preserve our shotgun housing stock and balance having a neighborhood with a large number of vacant houses…and later call it gentrification when other neighborhoods blatantly continue to vote down affordable living options?

Lifting up an inner-city neighborhood of 3,300, who would volunteer themselves for such a task?

He continues: Still believe our neighborhood association has set a city and national model for inclusiveness.

Hope today is a good day!

This originally appeared in the June 2019 issue of Louisville Magazine under the headline "Have You Seen Shelby Park?" To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.