Photos by Mickie Winters

Cover photo: Dogs Helping Heroes founder David Benson trains a service dog.

|

| Fourteen-year-old Trayceton Harmon with German shepherd Tommy. |

Tommy, a young German shepherd, stares at the closed bedroom door, ears up like two exclamation points. From the living room of the compact home in Tompkinsville, Kentucky, just north of the Tennessee border, Wendy Dickens asks, “Is he over by that door?” She gets up from the black leather couch and sees Tommy at the end of the hall. “You want Trayce?” Dickens asks the dog. She opens the door, and Tommy jets into the darkened bedroom. “Sometimes Tommy has to get in there just to look at him,” Dickens says. The dog will come out later and play with Trayce’s brother and sister for a while, then it’s back to spend time with 14-year-old Trayceton Harmon, who has been too sick to get out of bed for most of the miserably hot summer. For much of that time, Tommy has kept him company.

In Corydon, Indiana, Hoss growls quietly as he sits beside Darren Bennett on the couch, his head on the big man’s chest. The dog’s golden eyes watch everything. When Bennett stands, the dog stands. When Bennett walks into the kitchen to retrieve some paperwork, Hoss is so close that Bennett could reach down and touch his head at any time. When Bennett returns to the couch, Hoss sits on the floor and stares at him, waiting for permission to jump on the couch, to maintain full-body contact. They go everywhere together, which is saying something. Before Hoss joined his family, Bennett went nowhere at all.

In a yellow house in St. Matthews with pink hyacinth bushes along the sidewalk, a big black Labrador named Johnny Cash lies on the floor of a wood-paneled back room, chewing noisily on his toy. At a nearby table, John Wells rolls out story after story about his dog’s gentle exploits. “I went up to the VA hospital to visit this one guy. I walked into his room, and his daughter was in there. She’s 15, 16 years old, rubbing on her father’s hands, weeping.” Without a word from Wells, the dog walked to the girl and put his big square head under her arm, snuggling as close to her as he could. “The nurse starts crying. There weren’t too many people who weren’t crying,” Wells says.

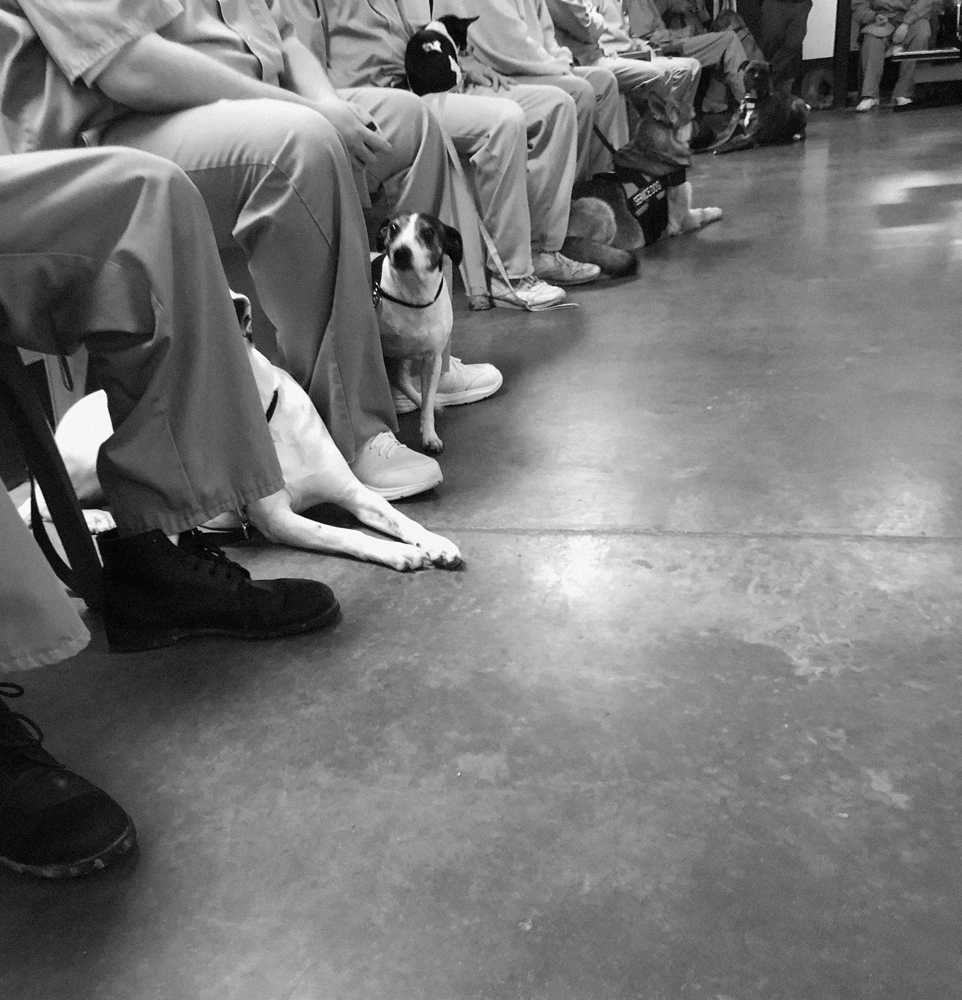

Twenty-four men clad in khaki sit along the walls of a big room in the Kentucky State Reformatory near La Grange. At the feet of each man, a dog waits quietly. There’s caramel-colored Tank, a moose of a dog with a puppy’s face, his handler one of two men in the room to top seven feet. There’s a shy little beagle peeking out between her handler’s legs. There’s Reese, a German shepherd with black-tipped fur. He’s so alert, he seems to be plotting something. Then there’s black-and-white Sarah, who, her handler proudly asserts, doesn’t have a thing left to learn. And then he demonstrates, walking her off-leash around the room, asking her to stay in the middle of a clot of men and dogs, and then calling her from across the room. It’s a perfect performance. Nothing distracts her. And then there’s Tommy, who in a few weeks will be introduced to Trayceton Harmon.

Finally, there’s David Benson. On a hot July morning, his own dogs — Boss, Wren and Pete — are out back while he sits on the shady front porch. His Jeffersonville, Indiana, home is on a green and leafy lot tucked behind an almost treeless subdivision. Benson is 39, just a shade under six feet tall and neatly built. His bald cranium seems domed to accommodate a little extra brain; he keeps his remaining hair trimmed to a fuzz. A few years ago, a call from his sister led him somewhere he hadn’t planned on going, which in turn led him to Trayce Harmon and his mom, Wendy Dickens; to Darren Bennett and the golden-eyed Hoss; to John Wells and Johnny Cash; to scores of inmates in a Kentucky prison; and, in the last few years, to a growing number of men and women who say their lives will never be the same because of his work. And the funny thing is, it all sort of started with cats. And television.

“As a kid, I spent a lot of time at my house with nobody there but the cats,” Benson says. “I think there was just a level of comfortability. They were just always there, always hanging out.” Besides the cats, there were hamsters and gerbils and Guinea pigs, and he talked to all of them. “The animal connection was constant because there was nothing (else) constant.” His sisters were out with friends. His mom, divorced, worked three jobs. It was him and the cats and the television at home in Franklin, Pennsylvania, about 90 miles north of Pittsburgh. He would watch TV shows about animals. And from a television show, he got the idea that he might want to train animals. His cats, however, proved too independent to tame.

David Benson poses with a service dog.

He kept the notion of animal training tucked away when his family moved to Louisville when he was 16, and when he enrolled at Eastern Kentucky University, and when he left school and worked as a server at the former TGI Fridays on Linn Station Road. He mentioned it to a regular at the bar one day. “You need to go see Matthew Duffy,” the customer told him. Duffy is a dog trainer and runs Duffy’s Training Center in Jeffersonville. Benson thought he’d get into dog training, build up his resume and who knows where that might lead.

Matthew Duffy, 60, wears a leash over his shoulder like a bandolier and gives off an aura of compressed energy, as though he might, at any moment, dash from the room, or fly around it. The center’s big training rooms echo with the smallest sound, but on this May afternoon they are mostly quiet. When David Benson showed up at Duffy’s 16 years ago with Spiral — a dog named for the Nine Inch Nails album The Downward Spiral — Duffy saw a young man with “a very happy, open spirit interacting with people and with dogs.” He was impressed by Benson’s desire to know more about communicating with his own dog. Duffy began teaching him; Benson was a quick study. When Duffy had an opening, he hired Benson part-time. Eventually, the job became full-time, and, in time, Benson was lead trainer.

Although Benson learned dog training from him, Duffy says the younger man has given it his own flavor, as any good trainer will. But at first, Benson says, he simply copied Duffy, using even the same words and tone. “His family used to make fun of me. They said they couldn’t tell who was in the training room, if it was me or him. Even my voice started to alter,” Benson says. But where Benson and Duffy are most unalike, Duffy says, is compassion. “I like the company of animals much more than I like the company of people. My good friends, my family, I love them, but I wasn’t nearly as empathetic toward the human condition as David has been all his life,” Duffy says. “I have grown into a much more compassionate human being because of my experiences. David came into the world that way.”

In June 2005, Benson’s brother-in-law, Army Maj. Chuck Ziegenfuss, was in Iraq. It was his first trip there but one of many deployments in a 22-year career. They were on patrol, following up on a report of an improvised explosive device. Then they found it. “It went off about three feet from where I was standing,” Ziegenfuss recalls. Launched from the bridge he was on, he landed in a canal that was more like a drainage ditch. His second-in-command dragged him from the water. “I started giving orders, telling people where to go and what to do. They were kind of looking at me, like, ‘Uh, boss? I think you might want to lay down for a bit.’” He’d lost part of his left hand and suffered major trauma to all of his limbs. The nerves in his arms were damaged. His right thigh was injured. His eardrums were blown. Shrapnel pierced his face. The concussion of the explosion caused traumatic brain injury. He needed skin grafts. He was rushed to the major trauma center in Iraq and evacuated to Germany, where doctors re-stabilized him and sent him to Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. He was there nine weeks. It seemed longer. For the next four years, he was in and out of hospitals.

Ziegenfuss is unemotional as he talks about the explosion, his descriptions clinical. But there was nothing matter of fact about any of it. Eighteen months after his injuries, he was a changed man. “I had been a pretty social person, whether it was going to the movies or going out to dinner, going for a walk, going out hunting or fishing,” he says. Now, he did nothing. “I was just home. It was work, then home, work and home.…I wasn’t really being a part of life, even of the life of my family.” (He has two children.) “I was sort of on pause,” he says. “Life had kind of stopped.”

Without Hoss, Bennett is sure his life would be limited. “I would still be sitting in the house,” he says. “I’m still very hypervigilant, but I know I have my buddy with me. I consider him my battle buddy.”

That’s when his wife Carren called her brother — David Benson. “What would you think about helping me get a service dog for Chuck?” Carren said. Benson began visiting breeders. He wanted to find a dog with a happy, friendly temperament and moderate energy. After comparing breeding pairs and their litters, he settled on Major, a little butterball of Labrador retriever. Ziegenfuss was caught in a fluffy trap. “The beauty of getting a puppy is you’re forced to get up and do,” Ziegenfuss says. For the first year, Benson advised his brother-in-law over the phone about basic obedience and manners training. When Major was a year old, Ziegenfuss brought him to Benson to work on service-dog commands. Ziegenfuss’s experience with Major planted an idea in his brother-in-law’s mind, Ziegenfuss says. “I was really excited about it, and David saw that growth over time.” It was the impetus for what came next.

Actually, several things came next. First, two more veterans asked Benson to train service dogs for them. Then, in 2013, the local chapter of the Military Order of the Purple Heart gave Benson their Patriot Award for obtaining and training a dog for the second veteran. A local television station picked up the story. Over the next two weeks, three people approached him and asked, “Have you ever thought of starting a nonprofit?”

He mentioned the idea to Duffy. “We talked about what it would entail, what it would mean, how I could help him,” Duffy says. Finally, one afternoon Benson and a friend sat on the tailgate of her truck in downtown Jeffersonville and brainstormed. Benson realized he already had most of the pieces in place: He had a supply of dogs through local rescue groups. He had trainers: the inmates at the Kentucky State Reformatory who train dogs rescued by the Humane Society of Oldham County. He had the support of Duffy and the training center. He had supporters in the people who had approached him about starting a nonprofit.

His mission, he decided, would be to provide dogs to veterans, first-responders and the families of veterans killed in service, the Gold Star families. Dogs Helping Heroes was born.

Although research on the efficacy of using dogs to help people with post-traumatic stress disorder is in its infancy, evidence suggests the intervention makes sense. No other animal bonds with humans the way dogs do. In fact, studies show dogs are a natural high and then some. Play with or pet a dog and your brain releases neurochemicals inexorably tied to well-being. Among these are oxytocin, the hormone released in contact as basic as a hug and as profound as sex. It’s also critical in mother-infant bonding. Also part of the alchemy are the natural pain-killers known as endorphins, often associated with the euphoria of a runner’s high. Dogs also trigger the neurotransmitter dopamine, which has a principal role in feelings of pleasure. Even prolactin levels rise in human-dog interactions; although the hormone is best known for its role in milk production after childbirth, it contributes to metabolism and immune function and sexual health in both men and women. It’s also involved in feelings of nurture.

A study published in 2015 in a leading research journal, Science, suggests that dogs have hijacked the circuits of human bonding. The researchers uncovered a feel-good feedback loop in action when we gaze into our dogs’ eyes. Levels of oxytocin rose in both dogs and humans after dogs and their owners locked eyes. The longer the look of love, the higher the rise in oxytocin levels. (Cats show some of this bonding, too. Their oxytocin levels rise when they play with us, but only by about 12 percent, compared with nearly 60 percent in dogs, one study showed.)

Trayce’s mom, Wendy Dickens, at home in Tompkinsville with son Trevor and Tommy.

This interlacing of human and dog began long before recorded history. Dogs were the first instance of domestication, before cows, pigs and chickens, and also before corn, wheat or rice. Just how long dogs have lived with humans is a contentious subject among researchers, with some concluding that dog domestication occurred as recently as 12,000 years ago and others placing the date as far back as 135,000 years ago. Either date appears to be long enough to make the interspecies relationship unique.

There’s no question that early humans (and later ones) put dogs to work. And dogs were also on the menu for many. But even 12,000 years ago, dogs were part of the family. In the 1970s, archaeologists uncovered a 12,000-year-old burial site in Israel where a dog lay in the arms of a human. Earlier this year, an archeologist/veterinarian studied a 14,000-year-old site in Germany in which a puppy was buried with a family. He concluded that the 28-week-old pup had been cared for by humans after it contracted distemper.

All of this makes dogs likely candidates for working with people with PTSD. But most of the evidence in support of their use is based on personal testimony. As compelling as those stories are, they don’t meet the standard of evidence-based medicine that places like the Veteran’s Administration demand. A preliminary study published this year, however, begins to build a case in dogs’ favor. Marguerite O’Haire of Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine measured levels of the stress hormone cortisol in 73 military veterans with PTSD, 45 of whom had a service dog.

In most of us, cortisol levels are low when we wake, but within a half hour, as we anticipate the coming day, cortisol rises, O’Haire says. For people with PTSD, however, cortisol levels don’t rise because they never dropped. “They’re always in a state of hyperarousal. They’re always on alert. So we don’t see the normal rise in cortisol,” she says. Veterans in her study collected saliva upon waking and again 30 minutes later, and overnighted the samples to Purdue. “What we found is that individuals who had a service dog — that cortisol rise appeared again,” O’Haire says. Service dog owners also experienced fewer PTSD symptoms than those without. But it will take further research to determine just what is going on.

Not that any of this research would matter much to Darren Bennett. He’s already a believer.

Darren Bennett and Hoss. |

It’s Friday, so Bennett is wearing red, which stands for Remember Everyone Deployed. His own deployment never lets him forget, even though he came back from Iraq a decade ago. Bennett is 6’3” and 300-plus pounds, with soft blue eyes. He’s the kind of man who can’t let his kids leave the house without telling his sons — 18-year-old Thomas and 16-year-old Trevor — he loves them. “Bye, son. I love you. Be careful! Fill your truck up!” Real dad stuff. He has an arm thrown around his other charge — his service dog Hoss, 90 pounds of watchful canine.

It’s hard to see Bennett and Hoss together without thinking of the Philip Pullman novels in which every character goes through life with an animal that is the external expression of the inner-self. Because if Bennett is the big softy to anyone who meets him — he greets strangers with hugs and will unself-consciously tell you that Laura, his wife, is an angel sent to help him — inside, he’s on high alert. He wakes up at night and, with Hoss, walks the property on which his mother’s and his own house sit. He’s making sure all is secure. When he attends classes at the University of Southern Indiana, where he’s working toward a sociology degree, he and Hoss sit by the door so he’ll be the first person to confront anything bad that might come into the room.

Bennett re-enlisted in the Army in time for the surge in Iraq, even though he’d already served for 13 years, because he felt a debt to a buddy who had just been killed in Afghanistan. He also believed it was his duty to protect and serve the nation. Even in Iraq, he put himself in harm’s way, volunteering to be a turret gunner, the soldier most exposed to enemy fire in a Humvee, his torso poking through the top of the vehicle. “I was the oldest out of all the people in my truck. The driver was 21. The truck commander was 23. I was 40 or 41, I don’t remember. I felt that if something was to happen, it should happen to me, not the younger people,” he says.

This month will be one year since he and Hoss were paired. In the beginning, David Benson taught Bennett basic obedience commands: how to walk Hoss on-leash, how to make him heel, how to call him. Hoss had learned both basic obedience and service-dog commands from his handler in state prison. Then it became Bennett’s duty to work with Hoss and polish his performance. Anyone who receives a dog through Dogs Helping Heroes has 10 lessons with Benson and other qualified trainers in order to earn three certifications, including the National Service Animal Registry Public Access Test, which allows the animals to go anywhere and is re-evaluated every two years.

Now, with Hoss at his side, Bennett can go out with his wife. He can go to the store. “I didn’t realize this,” Laura Bennett says, “but before Hoss, he never went into a Walmart by himself. There are just things you assume. When he would say he went to the store, in reality he would wait for the kids to come home to go to the store. He would go with them, or he would send them in.” It’s different now, Bennett says. “Now, with Hoss, I walk right into Walmart. I know he will get me out of a situation if something happens.”

In a way, Hoss came just in time, because Bennett’s symptoms were about to grow worse. In addition to anxiety, hypervigilance and other PTSD baggage, he started developing frightening neurological problems. He began having seizures and blackouts that include vivid flashbacks. In January, Laura noticed her husband stuttering on a word or two when he was anxious. Within two months, those occasional stammers became a constant stream. By July, Bennett’s speech was wracked by stuttering that grew more pronounced when he was nervous, which made him self-conscious on top of everything else. Even with all of this, Hoss has given Laura breathing room. When Bennett had a seizure one night after she had gone to bed, Hoss rushed into the bedroom and got her. “He’s not even trained to do that,” Bennett says. “He just knows.”

“It’s been great,” Laura says, “but it’s an adjustment. For the wife side of it, when a service dog comes into the picture — and it’s not negative — but you notice that he provides some of the things that you were doing. I didn’t stop doing what I did, I just know there’s extra help there. Hoss is by his side 24/7. I feel more at ease when I’m at work, knowing Hoss is with him here, that he’s taken care of.”

Without Hoss, Bennett is sure his life would be very limited. “I would still be sitting in the house,” Bennett says. “I’m still very hypervigilant, but I know I have my buddy with me. I consider him my battle buddy. He gets me through.”

Inmates are dog trainers at the Kentucky State Reformatory

Skyler Dorsett, a father of two with a tousle of curly hair, couldn’t believe his good luck when Benson called. When he applied to Dogs Helping Heroes, in the back of his mind were the Belgian Malinois dogs used by the U.S. Special Operations Command teams during his second deployment in Iraq in 2013-’14. “I instantly wanted a Malinois. I just fell in love with them,” he says. But when he said that to one of the military dog handlers, they discouraged him. “If you don’t have any training, and you don’t know how to do any training, I wouldn’t recommend getting one.” The Malinois, which looks like a lean German shepherd but with ears big enough to hear signals from extra-terrestrials, are known for their high drive, confidence and need for work and exercise. Dorsett figured he’d probably be just as happy with another breed, but he loved those dogs. Then Benson said Dorsett’s new dog would be a Belgian Malinois. “I about did a back flip!” Dorsett says

Dorsett tells Benson that story when the men meet at Bass Pro Shops in Clarksville, Indiana. It’s one of the 10 dog-training sessions each veteran goes through to win service-dog certification. Dorsett says his dog, Lyric, has already changed his life in the month he’s had her. “It’s really boosted my confidence going back out in public and going out in bigger areas like this,” Dorsett says, gesturing around the cavernous and noisy store. “Before her, I didn’t like going out. Panic attacks would spike.”

Skyler Dorsett and Lyric |

The training sessions are designed to bring both handler and dog into increasingly challenging situations, so that Lyric is prepared for whatever comes up and Dorsett experiences their competence as a team. Today, one challenge is the store’s pounding waterfall, something Lyric hasn’t seen before. The object is to help the dogs adjust to new things in a non-confrontational way. First, they walk up to the waterfall, then away. Benson explains what they’re doing: “If you take them right up, then they have to deal with it full throttle. That’s too much. But if you walk up and walk away, it takes the pressure off. It allows a brief introduction to noise, sound and smell, but there’s a quick exit.” Within 15 minutes, Lyric is able to hold a “sit-stay” right next to the waterfall, waiting for Dorsett to call her.

In another exercise, Dorsett pitches his floppy gray hat for Lyric to retrieve. It takes a few tries with little corrections before she executes it perfectly, shaking the hat like it’s her prey. Benson wants Dorsett to understand what just happened. “The big teaching piece here is increments,” Benson tells Dorsett. “You just keep putting all the pieces together.” During training, Benson says, “I want her to be successful. I want it to work, so if I’ve got to get in there — even if you would have had to walk all the way back to the hat and actually point at it, you do whatever you have to do to get it completed, to make it successful.”

Dorsett is delighted. “She just did better right there then she has done the whole time I’ve been working with her. That was lights-out. That’s not how it typically goes.”

“So what did you change today before you did the exercise?” Benson asks him.

“Maybe warmed up with things she’s comfortable with?” Dorsett says.

“There you go!” Benson says. “You’ve gained her respect. You’ve built your relationship. You showed her: We’re working together as a team.”

It can feel like Benson is a bit of a dog whisperer. When a dog doesn’t do what it’s asked, Benson figures out why and works that into his solution. “David really understands canine behaviors and psychology,” his brother-in-law Ziegenfuss says. But it’s more than that. “He also has that inner-peace and calmness that dogs absolutely respond to.” (Since bringing home his own service dog, Ziegenfuss has started Hero Labradors in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, which raises puppies to be used as service dogs.)

Benson exudes calm intensity. He holds eye contact. He listens. He provides no glib answers. Yet he says he was a hyperactive kid determined to always do the opposite of what he was told. When a gym teacher told the class to stand with their heels together and toes pointed out, without a moment’s hesitation Benson did the opposite and stood toes together and heels out. In every conversation, he mentions some idea he’s studied — Jungian archetypes, microexpressions, the ManKind Project — or some book that has influenced him — Autobiography of a Yogi, Nonviolent Communication, The Highly Sensitive Person, Decades Behind Bars. Yet he says he rarely reads a whole book, and instead just browses the index, picking out the parts that interest him.

One letter Wells wrote said, “I went out into this minefield to get a soldier that had his leg blown off.” “I don’t remember any of it,” Wells says. “It’s that PTSD.”

When he gets into something, he wants to master it. “I’m going to go full speed,” he says. His backyard testifies to his interests: there’s a slack line for tightrope walking suspended between two trees. He points to the back part of the lot, which he used for a while when he was bouldering (a kind of rock climbing). When he took up yoga eight yeas ago, what really caught his attention was a pose in which the yogi becomes sort of a human coffee table, performing a plank with the entire body balanced on one hand. (He demonstrates the move during two different conversations; it doesn’t feel like he’s showing off.)

He’s ambitious about Dogs Helping Heroes. “My ultimate goal is to be the largest nonprofit service-dog training program in the Midwest,” he says. How big would that be? “The ones in New York or Florida are placing about 20 dogs a month.” Those organizations have full-time paid staff and training facilities. They charge somewhere in the neighborhood of $20,000 for a service dog. Although Benson took a stipend from Dogs Helping Heroes last year when it cut deeply into his full-time duties at Duffy’s, normally nobody is paid. And he won’t be this year. The organization has no building, just a van. And it charges nothing when it gives a dog to a qualified veteran, first-responder or Gold Star family. Interviews, background checks and home inspections help determine who gets a dog. This year, Benson hopes to give away 20 dogs, but says it’s more likely to be 16. Last year, Dogs Helping Heroes trained and gave away 10 dogs; in 2016, it was four dogs; in 2015, two; in 2014, one.

Wells, who lives in the St. Matthews house with pink hyacinth bushes, returned from Vietnam in November 1968 after a year on the Da Nang Air Base as a Navy corpsman (like an Army medic) to a Marine division. Thirty-five years later, he was diagnosed with PTSD.

Wells has bright-blue, wide-open eyes, a mustache and a thatch of wiry gray hair. “I don’t really remember leaving Vietnam,” he says. “They had a party ready for me here at the house” — he lives in the house where he grew up — “and I didn’t even show up. I don’t know why.” He has reread the letters he wrote to his father while he was overseas. “I went out into this minefield to get a soldier that had his leg blown off,” one letter said.

“I don’t remember any of it. It’s that PTSD. It kind of kicks everything in the ass. You don’t realize how much it affects you until 20, 40 years later,” he says. He didn’t understand why he didn’t trust people, why he was hypervigilant, why he spent parties in the corner of the room watching everyone else. “I just put up a wall.”

About 8 percent of Americans will have PTSD at some point in their life, according to the National Center for PTSD. The number of diagnoses among members of the military is much higher. In one study of 60,000 veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan wars, 13.5 percent tested positive for PTSD, although other studies found rates as high as 30 percent in Iraq and Afghanistan vets. The National Center reports that some 15 percent of Vietnam veterans have PTSD now and 30 percent of Vietnam veterans experience it at some time in their life. Dr. Courtney McEuin works with veterans with PTSD at the VA Hospital in Louisville. She says PTSD is characterized by four kinds of symptoms: intrusive thoughts such as the occurrence of unwanted memories of trauma; avoidance of places that might trigger thoughts and feelings of trauma; negative thoughts and mood, such as persistent negative beliefs about oneself, others or the world; and hyperarousal, which can include irritability, reckless behavior, hypervigilance, and trouble concentrating or sleeping. PTSD symptoms often lead people to avoid taking action because they don’t want to think about it. “Sometimes, they’re in denial that there’s anything wrong,” McEuin says.

Although Wells was late in learning that he had PTSD, he was early to benefit from Dogs Helping Heroes as the second official dog recipient when he was paired with Johnny Cash. “It was like having a baby at first,” says Wells, who has two children and five grandkids. “I just got to know Cash, and what he can do to help me manage my problems, and everything started falling right in line. I started feeling a little better about myself.”

Play with or pet a dog and your brain releases neurochemicals inexorably tied to well-being. Researchers found that the longer we gaze into a dog’s eyes, the higher the rise in oxytocin levels.

Central in the training of the Dogs Helping Heroes dogs is the “at-ease” command. A veteran will say “at-ease” or use some signal — often putting their head in their hands — and the dog responds by giving the vet his full attention. He may jump up and cuddle, or paw gently or lick. Many dogs learn to recognize the anxiety that brings an at-ease command before the veteran does and will perform the at-ease behavior before the veteran realizes he needs it.

But Cash has taken it a step further. Wells is committed to helping veterans, so he and Cash are at the VA Hospital at least weekly and at many Dogs Helping Heroes events that attract veterans. And this is where Cash shines. For instance, Wells and Cash were at a meeting at the U.S. Veterans Outreach Center on Third Street when Cash walked across the room and began pawing another man. “Are you OK?” Wells asked the man after the meeting. The guy said he was fine. “I said, ‘Look, Cash does not get up and come over to just anybody and give what we call an ‘at-ease’!’” The man Wells was talking to broke into tears. “He was having a flashback,” Wells says.

“I’ve seen Cash get up on the bed with patients (at the VA). It just blew me away. My thing is, I promised them that if I get this dog, I would give back to veterans. I’m adamant about helping veterans.”

So is Cash, apparently.

One February morning, Benson stands in a room full of men and asks them to name the one thing they’re waiting for their dog to learn. The answers are varied: to respond more promptly when called, to bond more with his trainer, to show more confidence, to ignore other dogs. Then, over the next 2½ hours, Benson works with the men to reach those goals. He does this every week at the Kentucky State Reformatory as part of the Humane Society of Oldham County’s Camp Canine program. Although most of the dogs trained here will become family pets, a few will go to Dogs Helping Heroes applicants. Matthew DiBenedetto, an inmate serving 60 years for two murders, says there are other beneficiaries. “As much as we think these dogs are changing somebody else’s lives, these dogs are changing our lives,” he says. “It’s teaching you empathy, compassion, responsibility to care for another life. A lot of people don’t have those skills.”

The dogs help more than just the 20 men in the dog-training unit. “You’ve got guys on the yard — who’s not gonna smile when you see a dog wagging his tail?” The inmate dog trainers take their charges to the prison nursing-care unit weekly and to the psychiatric unit. “That’s the highlight of their week, seeing these dogs,” DiBenedetto says. Prison staff members have adopted many of the dogs that come through the program. And employees having a bad day often find their way to the dog-training unit for some canine therapy.

DiBenedetto singles out the inmate training Boaz, a tough-looking German shepherd with ragged ears. When Boaz came into the program, he was spoiling for a fight with any dog he saw. “The guy who’s got him, he’s an experienced handler. His timing for correcting Boaz on his behavior is phenomenal,” DiBenedetto says. Michele Culp, president of the Humane Society of Oldham County, says Boaz’s rehabilitation was considered a longshot. “When we first saw him, we wondered if he was save-able,” she says. He was. A few months later, his new owner’s Facebook page is full of photos of Boaz playing with puppies as though he were a puppy himself.

Benson has worked with inmates since 2010. They are his toughest assignments. “Inmates challenge me more than any other person I talk to,” he says. “Any chink in your armor, they’re going to find it. That was a hard lesson for me.” For instance, when he changed wording from one week to the next, his students were quick to call him on it. “They got out their notebooks. They came up. It was this whole big back-and-forth. It triggered my insecurities,” he says. “But it made me grow as a trainer.” Even after eight years training inmates, he’s still learning. “Not only are my leadership skills improving, the inmates’ leadership skills have been improving.”

DiBenedetto has trained dogs with several different rescue groups over 10 years. So far, he says, none of the training has been as successful as Benson’s. With other trainers, he says, “All throughout our training class, the dogs would be barking and just losing their minds. Whereas here, you’ve seen it for yourself, they’re just laying down. They’re quiet. They’re composed. It’s all due to Dave’s training and the amount of teamwork that we have.”

No one could figure out what was wrong with Trayceton Harmon when he was born. No two doctors told his mother, Wendy Dickens, the same thing. “They at first thought he was having seizures. Then they thought it was strokes. At one point they told us he had leukemia,” she says. He was developmentally delayed. “He didn’t walk until he was 18 months old. He didn’t say words until he was four. He didn’t talk in sentences so that you could understand him until he was six or seven. We were in and out hospitals with pneumonia, bronchitis. He had migraines. We could just not keep him well.”

When Trayce was 10 years old, he began losing his hearing. Then his vision started to go. They made an appointment with a neuro-ophthalmologist in Louisville, who spent 30 minutes examining Trayce. Then, for the next 3½ hours, he repeatedly sent a nurse into the room with more questions about Trayce. “I think he just saw the helplessness,” Dickens says. “I didn’t know what to do anymore. I think he just had a heart.” Trayce was only 63 pounds and slept 18½ hours a day. He had deteriorated so badly that Dickens worried she was about to lose her oldest child.

Four hours after they arrived, the doctor returned to the exam room and handed Dickens a piece of paper with his assessment. From what the doctor could tell, the little power packs inside of every cell — organelles called mitochondria — weren’t working right. It’s a devastating diagnosis. It isn’t simply one organ system that’s off, or one bodily function. It is a malfunction of the body’s most basic machinery that every organ and system requires for life.

The diagnosis came the year after Trayce’s hero, his uncle Army Sgt. Michael Cable, was killed in Afghanistan. Cable, Dickens’ youngest brother, was 26 years old. Somehow, the family thought that when Cable made it unscathed through his Iraq deployment, Afghanistan wouldn’t be a problem. “When he was in Iraq, we worried the whole time,” Dickens says. But they convinced themselves Afghanistan was no big deal. In the fog of magical thinking, they told Trayce that his uncle wasn’t in harm’s way. “When we found out, it was just crazy, when he was so close to coming home!” Dickens says.

“It really just rocked Trayce’s world,” Dickens says. “He was so confused since we told him it couldn’t happen, and then it did.”

Cable could get Trayce to do anything. One effect of Trayce’s disease is that eating can be difficult. He has trouble absorbing nutrients. But if he doesn’t eat, it can bring on life-threatening problems. When Cable was home from Iraq, Trayce was refusing to eat. So Cable bought him food from McDonald’s. “He told him it came from the Army. Of course he ate it. He thought everything Michael did was magical,” Dickens says.

Dickens’ family is remarkably close. Not only does Trayce’s dad go to all doctor visits with her (they’re no longer together), so do her parents. As the family tried to understand the implications of the new diagnosis, Dickens’ mother recalled a conversation she’d had with someone from Army Survivor Outreach Services after Cable was killed in Afghanistan. They had offered the family an emotional-support dog. Dickens wondered: Could they instead provide a dog to help Trayce? With the help of Mark Grant, then with Outreach Services, Dickens applied for a service dog.

Tommy arrived in February, just as Trayce was recovering from surgery to put in a gastric feeding tube, an ordeal that had depressed the normally upbeat boy. “It could not have been better timing,” Dickens says. And boy and dog were almost instantly inseparable. “The first week, it cracked me up, but every time Trayce would take a shower, Tommy would lay at the bathroom door and whine,” she says. They finally let Tommy stay in the bathroom with Trayce. They had to move Tommy’s crate so he could see Trayce at night. “Before Tommy, I was not a dog person,” Dickens says. “I was a little nervous. I never had a big dog in the house. He’s just like a kid now. He knows he can come and get us if he needs something. If I’m in my room and Trayce is crashing, he lets me know. They picked the perfect dog for him.” With Tommy at his side, Trayce is making friends at school for the first time. One day, he came home with phone numbers for two girls in his class. “It’s increased Trayce’s confidence,” Dickens says.

Tommy can pull Trayce in a wheelchair, retrieve things off the ground and help him get up when he needs help. It has made their frequent doctor visits easier on Trayce; they often have two or more appointments a week with doctors in Louisville, Cincinnati, Toledo, Atlanta and Nashville. With Tommy along, Trayce no longer hates the visits. He loves introducing his dog to his doctors.

Dickens’ two other children also tumble and play with Tommy. Her youngest, six-year-old Trevor Johnston, also has mitochondrial disease, so he has his share of doctor visits too. Her daughter, 10-year-old Brianna Dickens, is healthy. Dickens pointed out her daughter’s blue hair. “She never asks for anything. I feel guilty — for about a third of her school year we were gone. So when she asked if she could dye her hair blue, I said yes.”

In Tompkinsville, people were so interested in how Trayce and Tommy were doing that the family had a community barbecue. “When I worked for a diner in Summer Shade, we had customers who followed the whole story. They were so happy for Trayce. They really wanted to meet Tommy. That’s the difference in a small town — people here treat us like family.”

Recently, the family completed plans for Trayce’s Make-A-Wish trip to Disney World. Tommy will be allowed to ride any ride without height requirements. For one night of the trip, they’ll be in Daytona Beach. “Part of Trayceton’s Make-a-Wish was to take Tommy to see the ocean,” Dickens says. “Trayce has seen it, but he wanted his dog to see the ocean.”

This originally appeared in the August 2018 issue of Louisville Magazine under the headline "Creature Comfort." To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.