As with any culture, African-American culture is full of and rich with powerful, irreplaceable contributions its people have made to the world. It is important that we all attempt to take a step back and truly appreciate the African-Americans that have helped make this country what it is today. Educators, inventors, business men and women, activists, artists, leaders, and other pioneers throughout Black History deserve to be spotlighted and celebrated. Unfortunately, contributions from influential individuals are sometimes overlooked and forgotten. This is true no matter what culture is in question. Thankfully, there are those who dedicate their lives, or a substantial part of their lives, to enlightening the masses about past people and events that have made an unmistakable impact. One such dedicated individual lives here in Louisville, and he is sculpting a remarkable path from the past to the present.

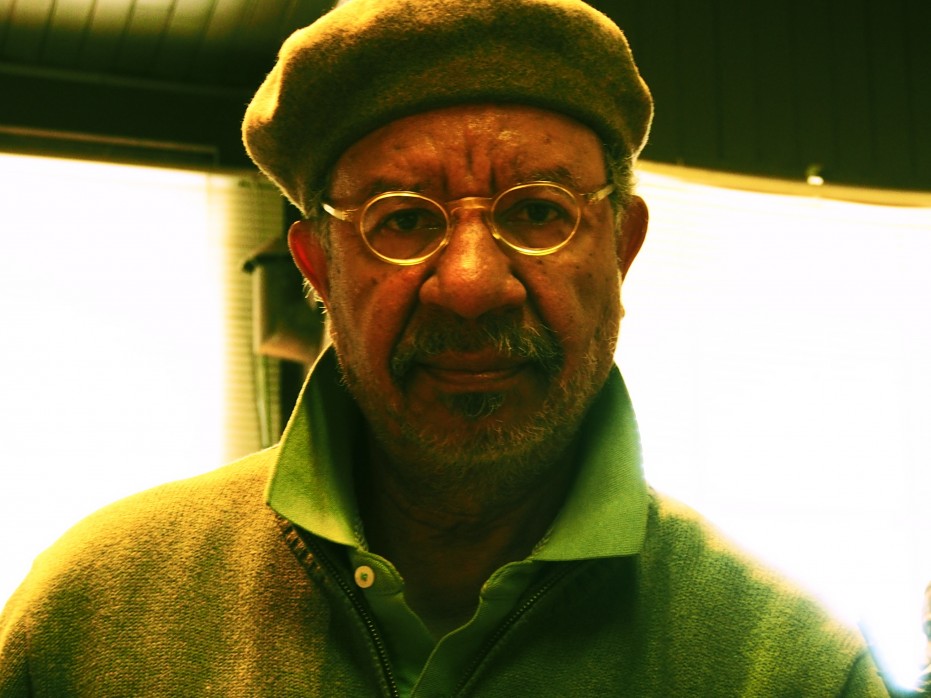

Keeping the impact of Black History literally in the faces of the masses with his art is a man, and nationally recognized sculptor, who calls Louisville, Kentucky his home - Edward Norton Hamilton. Although born in Cincinnati, he has lived nowhere except Louisville since he was two years old, and has created numerous sculptures for public venues from here all the way to Washington D.C.

When I asked how he came to live in Louisville at such a young age, Ed Hamilton encouraged me to read his book, The Birth of An Artist: A Journey of Discovery, to discover the staggering, yet heart-warming story of how he came to call Louisville home. Following his lead, I won’t divulge the story enveloping his life and relocation, and will encourage all to read the story of the young boy who grew up on Walnut Street (now Muhammad Ali Blvd.), who blossomed into a treasured figure in public art, and who relearned the meaning of faith, family, and true love well into his adult years.

The question that Ed Hamilton was more apt to answer was: Why Louisville? This city is not (and was not during the beginning of his career) exactly a bustling hub for the arts, let alone for the art of sculpting. Hamilton explained frankly, “We [he and his wife, Bernadette} could have gone anywhere. If you’re trying to make headway in an art career, obviously, there are several states you could approach that: New York, Chicago, L.A. But what happened was I discovered a sculptor here in town while I was still teaching out of Iroquois High School. Through him and his mentorship I engrained myself in Louisville.”

That sculptor was the late Barney Bright. During the 1950s, '60s, and '70s, Barney Bright was really the only sculptor here in Louisville being recognized for and making a living from being a sculptor. Mr. Bright was an invaluable person in Ed Hamilton’s life and career. In his book, Hamilton explains: “Barney opened the door of sculpting and I walked through it to become the sculptor that I am today. I hate to think of where and what I would be today had it not been for Barney – probably still teaching high school art, indeed, an honorable profession, but not one I would be happy doing. Barney was a master craftsman, sculptor and friend. He passed away in 1997 and I miss him very much.”

Beyond Barney Bright’s remarkable impact on his life, Hamilton’s decision to stay in Louisville was a combination of his family and personal roots that are so deeply anchored in this great city, and the desire to show the people of Louisville that he was - and is - a gifted enough talent to thrust his art out of here and onto a national stage. “If you do it [art] outside of your own arena, the people here, now, look at you different. So, I’ve always said, ‘You gotta get something outta here to make the people here know who you really are and what you can do.’ Then, all of the sudden, you get the ‘Boom!’ You get the stamp. You get approved. That’s only because you got something out of here, and now the outside world can see what you can do.”

Hamilton standing next partial bust of William E. McAnulty Image: Chris Gray

The pieces of art that Ed Hamilton has been able to share with the entire world are those that depict the struggle, perseverance, brilliance, and triumph of African-Americans throughout history. Through the Booker T. Washington Memorial at Hampton University; The Amistad Memorial in New Haven, Connecticut; The Spirit of Freedom Memorial in Washington, D.C. and several other public sculptures Hamilton has granted new life, purpose, and recognition to events and people in Black History. In a February 2015 issue of SoIn (Southern Indiana) Food and Entertainment magazine, Hamilton explained that he didn’t originally set out to make a career out of creating African-American centered art. “I didn’t choose it. It chose me,” he said. However, Hamilton couldn't deny that “there’s a lot of public art in the public sector. There’s not a lot out there that looks like us.” Here in Louisville, Ed Hamilton’s public art does not deviate from the unsuspectingly bequeathed path his career has taken him down.

The York Memorial on the Belvedere plaza downtown depicts the slave York, a black man who was vital to the success of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Although, he initially was not recognized for his indispensable contributions to the expedition – he was not even allowed to meet the President (Thomas Jefferson) upon the group’s return to Washington – York now stands as a heroic-size bronze statue overlooking the Ohio River. Not too far from Louisville, at the Kentucky State Capitol in Frankfort, Hamilton created the bust of Justice William E. McAnulty. McAnulty, who began his career in Louisville as a juvenile court judge in Jefferson County in 1975, became the first African-American judge to serve on the Kentucky Supreme Court in 1977, and he became the first African-American justice to serve on the Kentucky Supreme Court in 2005. Other Louisville works completed by Hamilton include the Lincoln Memorial at Waterfront Park and the Migration to the West statue in the lobby of the Frazier International History Museum.

What’s next for Ed Hamilton? Upon entering his teeming studio on Shelby Street, between Chestnut and Madison, filled with busts, miniature models, abstract pieces, and other intriguing creations that seemed to graciously receive me as I was happily overwhelmed by their presence, I saw what looked like four figures walking out of one of the back walls of his studio. A cutout that he’s working on, he told me, that he did not elucidate any further. However, it isn’t the only work-in-progress Hamilton is set to complete. He pointed out a small head of a man named George DeBaptiste that will become a larger bust for a soon to come park in Madison, Indiana. George DeBaptiste was a key individual in helping to free slaves through the Underground Railroad in Madison, and he became a prominent abolitionist in Detroit after he moved there in 1846.

Despite not initially choosing to give a voice and platform for outstanding African-American figures throughout our history, he continues to be an artistic emissary of Black History through his works. Edward Norton Hamilton is a talent that cannot be denied and whose impact cannot be overlooked.

Hamilton standing next to partial face model of LincolnImage: Chris Gray