Photos courtesy of Randy Napier's Facebook Page.

This article originally appeared in the January 2016 issue of Louisville Magazine.

To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, please click here.

Randy Napier posted a video to his Facebook page on July 2, 2014. Beneath it he wrote, “This song says it all. I’m sorry that I screwed up, but it is what it is.” In the video, the Taylorsville man sits forward on his living room couch holding a microphone. Because of the camera angle, his knees rise like knobby foothills in the foreground. Atop the back of the couch, stacks of laundry wait to be put away. “OK, I’ve tried this a couple times,” Napier says to the camera. “I’m gonna try it one more time. Hopefully we can get through it. If I cry a little bit, heck, we’ll deal with it.”

He reaches out of the frame to flip a switch, and as the music rises, he grabs a towel and wipes it across his eyes and nose. The song he’s about to sing is by country artist Tim McGraw. Napier could have written it.

“He said I was in my early forties

With a lot of life before me

When a moment came that stopped me on a dime.”

“I spent most of the next days

Lookin’ at the X-rays

Talkin’ ’bout the options

And talkin’ ’bout sweet time.”

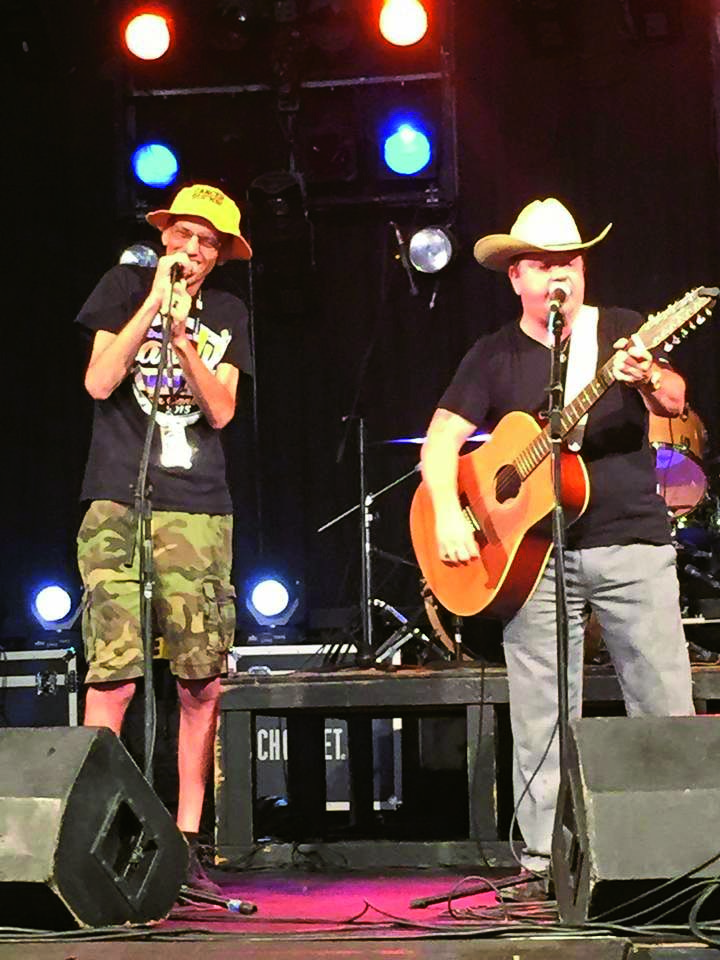

More than a dozen online videos feature Napier’s singing. They show him breezing through the National Anthem, gliding over the high notes with a country lilt, performing with his brother’s popular rock cover band, Jefferson TARC Bus, and singing on his living room couch in a voice rich and full, one country standard after another — Conway Twitty, George Jones, Charlie Rich. But this time he struggles, his voice uncharacteristically thin, with a slight off-pitch warble. Yet this is the recording people watch. The flawed one. One hundred and sixty-nine people have “liked” the original; 302 have shared it. No telling how many people have liked it and shared it from there.

As the next part of the verse starts, Napier steadies, grasping the mic with both hands.

“I asked him when it sank in

That this might really be the real end.

How’s it hit ya, when you get that kind of news?

Man, wha’d ya do?”

Napier’s right knee bounces with the music. He leans forward into the refrain:

“I went skydiving

I went Rocky Mountain climbing

I went two-point-seven seconds on a bull named Fu Manchu

And I loved deeper

And I spoke sweeter

And I gave forgiveness I’d been denyin’

And he said some day I hope you get the chance to live like you were dyin’.”

In the song’s final moments, Napier fights back tears. Viewers have already given up that battle.

It was 1:30 p.m., April 16, 2013, and Napier, at 47, was a little older than the man in “Live Like You Were Dyin’.” He already knew the chest pains that had sent him to the emergency room more than once had nothing to do with his heart. A few days earlier he had visited the Robley Rex VA Medical Center off Zorn Avenue for an endoscopic exam of his upper gastrointestinal tract. Doctors had sent a scope down his throat to just beyond his stomach to take a look around. What they found was an ulcer. Napier’s doctor told him it was the biggest one he’d ever seen. They’d know more after a lab analysis of a tissue sample. Those results would determine what came next.

Napier tells this story in July, sitting on the same living room couch seen in so many of his videos. There are a few more stacks of laundry around the room and a small table near the couch cluttered with medicine bottles. Napier gestures toward the master bedroom, just beyond the dining room’s burgundy walls. “I think I was in my bedroom when the phone rang,” he says. “I like to walk around when I’m talking to somebody, and I was walking back and forth.” As he neared the front door, the far end of his pacing circuit, the doctor delivered the news: You have stomach cancer.

“It was like somebody hit me,” Napier says.

That was a Tuesday. On Thursday he talked to a surgeon. On Monday he visited an oncologist. On May 17 the surgeon removed his stomach and spleen.

Thousands of people know this story. Napier told them on Facebook, creating an autobiography in single lines and short paragraphs, the last words of a man facing an illness with an inevitable course. And with these messages, he moved into the vanguard: As so many of us take to the Internet to register minor irritations and major pleasures, the meals we eat and the marriages we end, the children we bear and the anniversaries we celebrate, a growing number turn to Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and blogs to write their final chapters, to shape the public perception of perhaps the last private sphere. Randy Napier is part of that — the first generation to die out loud.

We no longer go gentle into that good night. And that is a good thing, says Amy Tudor, a poet and professor at Bellarmine University. Tudor has spent several years exploring the subject of death and teaching it to college students. This fall she led a six-week series at the Louisville Free Public Library called “The Death Class: Exploring the History, Attitudes and Culture of Death in America.” “We were expecting maybe 40 people. I got 300,” she says. And more people kept coming. “It was a madhouse. It was a fantastic experience, but it was really, really intense. We had dying people who attended. We had people who were talking about death for the first time,” Tudor says. “I did not know what I was getting into, but at the end of it, I was so glad I did it.”

Tudor sees something both inevitable and welcome in the impulse to share one’s last moments with the online world. It’s not death on the Internet that’s the weird thing. What’s weird is the private unspeakable that death has become.

“Before the Civil War,” Tudor says, “a single person’s death was a communal event. Everybody came to you. Everybody came to say goodbye. Everybody was aware that somebody was dealing with death. Everybody pitched in and helped. We don’t have this community anymore. We’re not living next to our families anymore, most of us. When we do go to keep vigil over somebody who is dying, most of us are separated from everybody else we know.” The World War II generation grew up with death in the home. Grandparents died in bed and were laid out in the parlor. Yet that generation’s own deaths have often taken place in hospitals and nursing homes, far from the public sphere. Detached from communities, they slip away in silence, in a strange and profound seclusion.

When her own father lay dying in 2008, Tudor traveled to Washington, D.C., to see him. It was a rushed dash, a trip she took alone. “I saw my father for the last time on my birthday, Nov. 2. I had to teach Nov. 4. He died on Nov. 4,” she says. So instead of a lengthy vigil, she had back-to-back 11-hour commutes. “It’s not that Bellarmine was like, ‘You must be at work!’ But because I teach, it’s just that kind of job. Everybody’s got that problem. The death vigil can take two, three, four weeks in intensive care or in a hospice setting. Whose work is going to give them four weeks off?”

Social media changes that. Now, we can all be at the bedside, at least virtually. Even the bedside of a stranger.

Napier was already a Facebook addict when he received the diagnosis of a stomach cancer called linitis plastica. Sometimes referred to as “leather bottle stomach,” it invades the stomach’s muscular walls, turning them rigid, incapable of expanding to accommodate food, unable to churn to break food down. It’s a rare version of a disease already uncommon in the United States. This year, an estimated 1.6 million people will be diagnosed with cancer, according to data from the National Cancer Institute. Of those, 1.5 percent, or about 25,000, will be stomach cancer cases. There’s no breakdown for how many cases of linitis plastica will be among the stomach cancer diagnoses this year. But NCI data from 2008 to 2012 provides a clue. During that period, linitis plastica accounted for .006 percent of all stomach cancers. Bottom line: The number is tiny.

The chances of surviving linitis plastica are beyond discouraging. One research group, which tracked 120 people, recorded a median survival of eight months from diagnosis. (The median represents the middle point in a series, so half of the patients died sooner, half later.) If the patient had surgery similar to Napier’s, median survival rose to 17 months. If treated with chemotherapy alone, another study showed, median survival barely crested the one-year mark. But the number of patients in the second study was so small, the authors acknowledged, the results failed to reach statistical significance, which is another way of saying these results have the validity of a coin toss — but a coin engraved with “bad” on one side and “worse” on the other. Napier would eventually have chemotherapy twice and radiation.

Before the diagnosis, Napier’s online shtick was one-liners. He was funny, maybe even a little crazy, the guy who might do anything. And Facebook was his family photo album. Here he is at the Kentucky Speedway preparing to drive 168 mph — a privilege one can buy for a few hundred dollars. Here he is out on his BMW motorcycle, cruising with friends. Here he is in Honduras with his son Josh, now 25. When he wasn’t putting up photos, he was making jokes, several times a day, usually borrowed from other sources:

April 8, 2011: “If it’s stupid but it works, it isn’t stupid.”

Later the same day: “The only honest people in this world are small children and drunk people.”

April 11, 2011: “Do these pants make me look interesting?”

Dec. 31, 2012: “Sometimes for fun, I slip condoms into the carts of little old ladies at the grocery store and then watch the clerk’s reaction.” (Posts have been edited for clarity.)

Amid the jokes were a few serious messages, most honoring the military. Napier entered the Army at 17 with a goal of earning his GED and qualifying for the Air Force, which he did, serving a combined total of 12 years. The rest of his Facebook feed was a mix of conservative political beliefs — “United Nations is Satan” or “I was anti-Obama before it was cool” — and inspirational messages: “When something bad happens you have three choices: You can either let it define you, let it destroy you or you can let it strengthen you.” Much of it was entertaining, little of it intimate. This was Napier at his most personal: “My mom makes the best potato salad in the whole world, I’m just saying.”

But in early April 2013, a more disclosing man emerged.

April 12, 2013: “This ulcer is killing me. I can’t sleep because of the pain. I just hope they can do something about it quickly.” Still, he could never be completely serious. The next day he posted a photograph of an infant curled up with three pug puppies.

Then, on April 16, 2013, hours after he learned it himself, he broke the news of his diagnosis on Facebook:

“OK, I don’t know how to say this, so I’m just going to say it the best I can. I found out today that I have stomach cancer. Everything is fine. I haven’t found out everything about it, but I am a fighter and I have a great support group in my family and friends. I am a pretty private person, but it is going to come out eventually and I would rather it come from me. So if you would, say a few prayers for me that everything works out. Love, Randy.”

He also changed his Facebook profile to show his profession as “Cancer fighter (killer).” Before that status change, he was retired from the post office. A series of knee surgeries had forced him into an early retirement, although he asked to be given a job in maintenance, where, he believed, his knee problems wouldn’t be an issue. “They’d rather see you go than to use you,” he says. He’s still angry. But that anger never seeps into his online persona. Ask him about bad news, and he has a stock response: “It is what it is.” The post office. The retirement. The cancer. It is what it is.

When he chose to take his illness online, Napier joined a growing group of people publicly confronting lethal illness, some of them celebrated. When Roger Ebert, the Pulitzer Prize-winning movie critic for the Chicago Sun-Times and cohost of "At the Movies," lost his voice to cancer, he began an online journal that covered everything from movies to recollections of growing up Catholic to thoughts of his own death. NPR news host Scott Simon tweeted his mother’s death in 2013:

Her passing might come at any moment, or in an hour, or not for a day. Nurses say hearing is the last sense to go so I sing & joke.

Mother cries Help Me at 2:30. Been holding her like a baby since. She’s asleep now. All I can do is hold on to her.

Heart rate dropping. Heart dropping.

For Bellarmine’s Tudor, all of this makes sense, including the way Simon made his mother’s death public. “To me it felt very natural. That’s exactly what someone would do if they were spending all that time in the ICU or all that time in that waiting room,” she says. “To watch somebody go through that process as unflinchingly as (Simon) did has instructed us really helpfully.” Witnessing someone else go through a loved one’s last hours helps us understand what we may face. “We don’t talk about how to deal with dying. Are you supposed to just know? Having steps, having a pattern to follow, I think really helps people. I don’t think we have that.” In the 1860s, Tudor says, people believed that a good death followed a formula. First, the dying person had to be told he or she was dying. The dying person was to profess sorrow for sins and a belief in Christ. Because people believed that a dying person couldn’t lie, deathbed confessions were a serious matter. People were to die surrounded by family, not friends, and the dying person was to pass his or her last instructions to children and spouse, along with wisdom to guide them. The "Ars Moriendi," the art of dying, essentially a manual for a good death, had been around in some form since at least the 15th century. Even Robert Bellarmine, the Jesuit cardinal for whom the university is named, wrote two volumes on the subject.

Probably few of us would take comfort from some of the deathbed rules in vogue around the time of the Civil War. The dying were called to be stoic. “People had this magical attitude that how you looked as you were dying showed the state of your soul, in terms of your salvation,” Tudor says. “So if you were screaming, yelling, whining, writhing in pain, it meant you had something unresolved that you hadn’t dealt with.” The expression on your face when you died would be the one you took into eternity.

That’s not how we approach death today. Today, the dying must be optimists. Cancer patients are called to become “warriors,” Tudor says. “You do battle. You don’t die; you lose your battle. You have your fight,” she says. Even people with late-stage cancer avoid hospice in the belief that turning to hospice means giving up. It’s not that fighting cancer is wrong, Tudor says, but looking for that beat-all-odds cure, thinking about the one guy who got better once, can be impoverishing. Tudor talks about the work of Stephen Jenkinson, who teaches about “dying well” through his Orphan Wisdom School in Ontario, Canada. Tudor, paraphrasing Jenkinson, says the dying person is like someone “put in a boat on a very vast ocean. Do you ask the person to set the course by the Milky Way, the stars that you always see? Or do you ask them to set the course by Halley’s comet?

“A lot of our medical approach is, set your course by Halley’s comet. What that does is, people die not dying. They die not dealing with their death until the last 24 hours, when they realize it’s too late,” she continues. “And dying is a wonderful opportunity for you and your loved ones to make meaning of your life. And if you spend all that time denying what’s happening to you, you’re not doing that.”

Stacey Napier, 48, has long gold-brown hair that reaches nearly to her waist and eyes shaped like the sun setting on the ocean. But when her husband says she has the eyes of a child, he’s talking about her outlook. She’s trusting. She sees promise. She rarely worries that someone is working an angle. Maybe that quality had something to do with the way she was swept into Napier’s story, because when his April 2013 diagnosis came through, they’d been out exactly twice. Ask her why she didn’t run right then, and she can’t say. She talks and talks, trying to work it out, but never reaches an answer. They met when she went to see Jefferson TARC Bus play. Afterwards, Randy tried to “friend” her on Facebook; she ignored it. When she finally accepted, he asked her to call him. She wouldn’t. When she finally did, he asked her out. In a rare instance of pessimism, she called a friend instead.

“I don’t know him. I don’t want to be chopped up in little pieces,” Stacey said.

“He’s a great person. You’ll have a great time,” her friend replied.

On their first date, he declared, “I’m not marrying you.” She told him she’d never live under another man’s roof. They both lied.

On their third date, Napier took her to a funeral home. “He said I was lucky that he let me in on it,” Stacey says. “So we’re sitting (in the funeral home) making plans with the lady about how he wants his funeral to go.”

“And we’re laughing,” Napier says.

“I don’t know how we did that,” Stacey says.

“I try not to take things too serious.”

“But it was serious! You were taking it serious. You were taking care of business.”

“Yeah.”

“I actually took a picture of the funeral home sign and said, ‘Yeah, this is our third date,’” Stacey says.

The Napiers live in a small subdivision of newer brown and beige brick homes plopped in the middle of farm fields a few miles north of Taylorsville. There are four cars and a van in the driveway and a BMW motorcycle and a gleaming red 1972 Corvette in the garage. Just inside the front door is the hospital bed where Napier sleeps, and above it, two small framed prints, one of Snoopy flying his doghouse, the other of Snoopy hugging Charlie Brown. Sometimes, Stacey will creep into the narrow bed with her husband. “We wake up the next day,” she says, “and that makes everything better.”

Since his stomach was removed, Napier has relied on tubes for his nutrition, first with a tube through his nose and now via a giant syringe pushed into a port in his belly. Keeping on weight is impossible. Around the time of his diagnosis, he weighed about 250 pounds on a 6-foot-3-inch frame — too big, he admits. But now he’s 130 pounds, with hollows around his eyes and sharp cheekbones. “I hate what I’ve become,” he says.

“But it cured your diabetes,” Stacey says.

“And my cholesterol.”

While we speak in July, every now and then Randy extends his arms to lift himself slightly from the fat couch cushions. He’s searching for a more comfortable position. But there is no comfortable position. Across the room, Stacey shakes her head briefly, signaling me not to fuss over the look on his face, the evident pain. His voice is weak, sometimes like an old man’s, other times like a small boy’s. I have to sit beside him to hear him. Then Stacey says to him, “Sing my one song.”

“What’s your song?”

“You know. It’s a George Jones.”

The transformation is instant. His voice resonates in his chest “He said I’ll love you ’til I die,” he begins, singing the first line of “He Stopped Loving Her Today.” He stops. “I don’t want to do that,” he says. “It makes me cry.”

Stacey is comfortable with her husband’s life online. When he started a Facebook group for cancer patients and their families, Faces of Cancer, she had only one request: “That phone’s in front of your face enough. Just promise me it’s not gonna take over our time too.” He uses his smart phone to create an almost documentary view of his own illness. No matter the procedure, he wants pictures. Some are tough to look at. In one he slumps over in a chair like a defeated boxer. He is bare-chested, with a blanket across his lap. Tubes and wires run everywhere. Another reveals the abdominal opening where his food goes in. Another is a close-up of the chemotherapy port in his neck. It’s all part of the story, so it goes on Facebook.

Randy’s son Josh works at Market Street Barbers in NuLu. I stop by late one chilly afternoon and we sit out back and talk. I ask him about his dad’s Facebook posts. Josh squirms in the cold metal chair before clasping his hands in front of him. “No comment,” he says. “Let’s just leave it there. No comment.”

For some families, these extended online goodbyes start as a purely practical matter. In 2010, a former co-worker of mine named Kathy English, of Bay City, Michigan, began posting Facebook messages about her eight-year-old son, David, who had recently been diagnosed with advanced glioblastoma — a brain cancer. I hadn’t lived in Michigan for more than a decade by then. Pre-Facebook, I’m certain that years might have passed before I learned of her son’s illness. There’s a fair chance I might never have learned of his birth. Now I held a strangely intimate ringside seat to her family’s struggles, drawn into this world of two-hour treks to a hospital in Ann Arbor, school assignments completed at home, and a smart and funny boy whose life was ending just as I was meeting him.

“I just could not talk about it in front of him,” English said when we talked last year. She was always with him, staying in his room at the hospital. “Some things you just can’t say in front of your kids.” So Facebook provided a space for grown-up conversations. More practically, it eased the burden of keeping everyone up to date. “Everybody calls and they want their own private conversation with you. Thank you, but gosh, there’s like 50 people who could be calling at any given time, and that’s just family. I can’t do that every day,” English said.

Being public about David’s treatment left the family vulnerable. In 2012, all of English’s Facebook connections knew David was having an MRI. The exam showed his tumor was back. “People were like, ‘How’d it go?’ A week passed before I could say, ‘Not good.’ By that time, we were back in the hospital because he was having such pain and symptoms from the tumor,” English said.

“I wanted time alone with David before all of the I’m-so-sorrys came in. I wasn’t ready to think about that.”

When David died, at age 10, social media no longer seemed adequate. “I thought, ‘I can’t put that out there,’” English said. First, she needed to call family members. By delaying a public announcement, she also shielded the family from the barrage of phone calls that were sure to follow. “It was many, many hours later that I posted that he died, after the family had been notified,” she said. It’s hard to believe, but not everyone contacts family first. “All the time I’m seeing posts by people about ‘Thanks for letting me know dad died — had to read it on Facebook,’” she told me.