This article originally appeared in the December 2015 issue of Louisville Magazine.

To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, please click here.

When Napier had the surgery to remove his stomach and spleen in May 2013, he and Stacey had been dating a little over two months, yet she was the one who sat up with him through the night in the VA’s intensive care unit. She didn’t want the vigil left to his son; she wouldn’t want her own two kids, both in their 20s, thrust into that lonely role. Randy’s sister and three brothers had to work the next day, so she took it on. Sometimes Napier would shake. Sometimes she had to remind him to breathe. The next day, as she fell into an exhausted sleep, she asked herself for the first and last time, “Can I do this? I don’t know if I can do this.” Josh stayed with his dad that second night.

If the surgery scared him, Napier never showed it. Online, he was optimistic, even ebullient.

April 20, 2013: “Day five after being diagnosed with my stomach cancer, and I must say I have never felt more alive. Plus the love from my friends and support and love from my family is more than any man could ask for. I’m truly blessed.”

April 21, 2013: “I used to hate mornings but now there’s just something special about watching the sun come up.”

April 22, 2013: “Realizing what life is about too late is a sad thing. Figure it out now.”

April 22, 2013: “I’ve got cancer, it don’t have me!”

April 25, 2013: “Live every day like you stole it!”

April 28, 2013: “Nothing makes you feel more alive than when you are facing death.”

Behind the scenes, though, he acts on an apparent innate sense of his true odds for survival.

“Yeah, I already bought my casket,” Napier tells me.

“It’s in the van in the driveway,” Stacey says.

Why isn’t the funeral home hanging onto it?

“Well, the way it was, I found a good deal on a used one. . .”

It takes me a moment to realize he’s kidding.

“It was a really good deal,” he continues. “I’m fairly frugal on these things sometimes, and I got a really nice cherry wood, Amish-made casket for eighteen-hundred bucks. They are about eight grand if you just go buy a casket like that. I asked around and found somebody that sells them wholesale.” He tracked the casket down before surgery. Not long after his operation, he and his brother Dave Moody drove nearly as far as Chicago to pick it up. When he got it home, he even climbed in to make sure it was comfortable. Talk about confronting death.

“That’s part of life,” Napier says.

“It’s been in my face since day one,” Stacey says.

“Dying’s part of living. I don’t want to die,” he says.

Stacey talks over him — “He took care of everything before surgery…” — but he keeps talking. They’re both talkers, and neither is shy about taking the floor.

“I don’t want to die,” he says. “It ain’t like, ‘Hey! Look at me! I’m dyin’!’ But I don’t want them having to make — ‘Would he have wanted this? Would he have wanted that?’”

The day before his surgery, Stacey had posted to her own Facebook page: “God doesn’t put someone special in your life just to take them away, right?! Especially someone who has made his way deep into your heart and soul!!! I would say no way!!!”

“I’ve always known it would get me,” Napier says. Stacey starts to say something and pauses.

Just for a moment, she looks lost.

At some point during his illness, Napier made a half-hearted attempt to send Stacey on her way. “I didn’t want her to go through this crap, to have to go through this. That ain’t right to put somebody through this,” he says.

“He was actually trying to push me away,” Stacey says. “I didn’t notice.”

“Maybe I suck at it. Maybe I didn’t try hard enough. Maybe I was hoping you would stay,” he says.

Stay she did. On Nov. 1, 2014, they married. It’s his third marriage, her second. On Nov. 16, 2014, Napier posted: “I had a hard time deciding to get married. I asked Stacey, ‘If you knew I was to die in six months, would you still want to marry me?’ And she said, ‘It would hurt either way, so why not be your wife?’”

Officially, he’d been in remission since Nov. 1, 2013, but as the end of 2014 neared, every photograph he posted marked the inexorable advance of his illness. Napier was in and out of the hospital dealing with the various complications with his feeding tube and esophagus. He worried that malnutrition was as likely to take him as cancer. It was all exhausting. On Dec. 10, 2014, he wrote, “Nobody wants to live more than me to one day see my grandchildren, to see my son, who’s a great musician, playing a stadium concert, or to grow old with my beautiful wife, but I am just tired.”

Then, on March 18, 2015, he learned his cancer was back. “Today I was told I have three months to a year to live without chemo, and (they’re) not sure if chemo will even make a difference at all.…Please, no pity. Just prayers. Thank you.” Bravado about beating cancer vanished. His goal now, he wrote, was to reach his first wedding anniversary on Nov. 1.

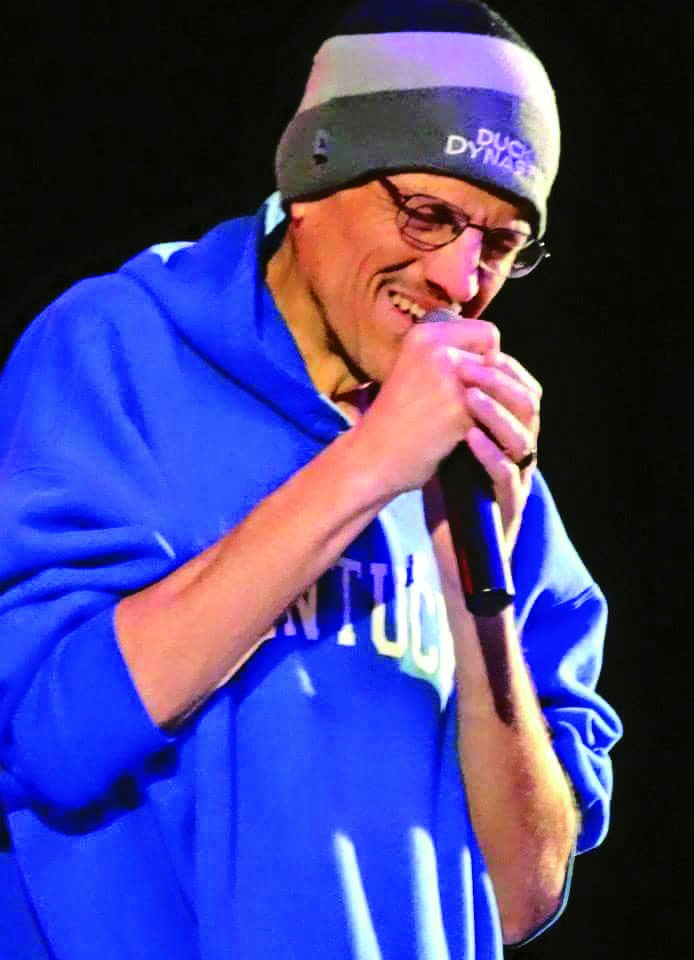

Other than that, nothing changes. He’s out on his motorcycle. He’s skydiving for the second time — something he wanted to do long before he got sick. Here he is with Stacey at the beach, his gigantic surgical scar like a puckering face etched into his torso. He takes his grandson Brayden Simmons to visit the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. Up-and-coming country music performer Shane Dawson of Mount Washington, Kentucky, and Louisville songwriter Terry Hall meet with Napier and together they write a song about his life called “I Hope I Made Them Proud.” The YouTube video of Dawson singing the song drew 60,000 viewers within days of its release. It’s been reposted many, many times. A man in England asked to have it played at his funeral.

Napier hosts his second Randy’s Band Aid fundraiser and raises $28,000 for Shirley’s Way, a Louisville nonprofit that helps local cancer patients pay the bills. (The year before, Randy’s Band Aid raised $6,000 for Shirley’s Way. It takes place again June 5, 2016. Proceeds from “I Hope I Made Them Proud” also go to Shirley’s Way.)

But he grows weaker by the day. In each photograph he is thinner. It seems impossible he can lose more weight, and a few weeks later, he is gaunter still. Deep hollows where muscles once shaped shoulders and arms. The keyboard of his ribs lies exposed just beneath the skin. The intensity of his high-wattage smile, which often reveals both uppers and lowers, becomes softer, quieter. By October, Stacey’s family takes turns staying with the couple. Any posts on Napier’s Facebook page are now from friends and family. They send encouragement and prayers that he can meet his goal and live until his first wedding anniversary.

Some days Napier is strong enough to sit up in bed and talk; other days, nothing goes right. Each time he wakes up, several times a day, he asks, “What day is it?” One Sunday in October, Stacey helps her husband to the bathroom and he collapses. Stacey’s mother rushes to him with pillows and blankets as Stacey guides him gently to the floor. Gradually they work a sheet beneath him to pull him up and get him back into bed. From somewhere deep in his fog, he tells Stacey, “I’m ready to go home.” She and Josh grasp his hands, prepared to say goodbye. “It was quiet. We sat there — it was like 20, 30 minutes,” Stacey says. “Then out of the blue, all of a sudden, Randy just opened his eyes and said, ‘What are you doing? I’m not going anywhere yet.’”

“We just looked at each other like, what the hell just happened? And that’s when he started coming out of it. Monday, when the hospice nurse came over, he was sitting up in bed.”

Then, on Oct. 22, someone posts a photograph on Napier’s Facebook page that shows how far the journey to his first wedding anniversary really is. He is lying on his back in the hospital bed in his living room, his mouth wide open, his eyes sunken and dark. The tendons in his face and neck stand out like a drawing in an anatomy book. Stacey is curled up beside him, her eyes closed, her face like a mourning Madonna from a Renaissance painting. Four days later, Steven Randall Napier is dead. His wedding anniversary is five days away. He was 49 years old.

The fact that Napier didn’t live long enough to celebrate his one-year anniversary has important consequences for Stacey. Because they were married five days short of a year, she is ineligible to receive her husband’s veteran’s benefits. She’ll have to give up the house. She can’t afford it. A former hairdresser, she has fibromyalgia and has been on disability for the last several years. Shirley’s Way is trying to pitch in. When Napier was dying, someone told a complainer it was time to “Randy Up,” says Shirley’s Way founder Mike Mulrooney. (He named the organization after his mother, who died of liver cancer almost three years ago.) “It means suck it up and stop complaining and tough it up a little bit,” Mulrooney says. So the organization made a special T-shirt that shows Napier singing, with the words “Randy Up.” The profits will help Stacey. Every day, she still posts to Randy’s Facebook page, as do friends and family, but like most things on Facebook, it’s a curated kind of grieving. The real, soul-crushing stuff — she keeps that offline.

Last summer, Napier told me that cancer had made him a better person. “It was all about me. I mean, seriously, I was all about me. Everything was about me. I didn’t like who I was,” he said. “That’s the one thing, why I wish I could make it, be around longer, because I’m a bit better person now. So I wish I could have more time.” Josh walked through the living room as his father said this. I asked Josh if that was true. Had he seen his father change? Yes, he said. “But you were always giving,” Josh said.

“I think all humans have this inner self-guilt over things we do,” Josh tells me later, after his father has died. Recognizing that guilt, Josh says, is a sign that his father was self-aware. “A lot of people aren’t self-aware. I think he was.” He was an example of something Ernest Hemingway said, Josh tells me. “There is nothing noble in being superior to your fellow man; true nobility is being superior to your former self.”

Outside the Newcomer Funeral Home on Dixie Highway, there are no more parking places. Inside, the chapel is packed. Men line up along the walls and more form a knot at the back. Several people wear the bright-orange “Cancer Sucks” T-shirt that Shirley’s Way sells to raise money. Some of the people at the funeral only knew Napier from Facebook. “People came up and said, ‘I know you don’t know me. I never met you. I never met Randy,” Stacey says. But the crowd would have been large even without the Facebook connections, his brother Dave Moody says. For Moody, the whole Facebook thing was a little hard to take, at least at first.

“The pseudo world, Facebook, seemed silly to me,” he says in his eulogy. “Randy’s fight was very public, and it was hard to watch some days. I didn’t want to share him with anybody but my family. How could you know somebody through Facebook? How could you love somebody you only know through Facebook? I’ve known him 44 years! In the pseudo world of Facebook, we don’t know anybody but by what they’ve told us. We don’t know anybody deeper than that. There’s no scratching the surface. How could y’all know Randy? I know Randy. I know Randy.”

It took another cancer patient to change his mind, a young woman named Lauren Hill, a freshman basketball player at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati. She died earlier this year after a very public fight with brain cancer. “I was all about Lauren, rooting for her. I had no idea who Lauren really was,” Moody says in his eulogy. She had raised more than $1 million for pediatric cancer at the time of her death. Moody came to realize that his brother’s nearly 3,000 Facebook friends, and the nearly 5,500 others who knew him through the Faces of Cancer Facebook support group, felt the same way about Randy as he had about Lauren.

“Randy was loved by everybody. He was loved regardless of Facebook. Believe me when I say, he was an astounding human being,” Moody says. “He lived an interesting life. He finished up as good as any human being could finish up. He showed everybody how to live with an illness and not let it define you, not let it control your life.”

Shane Dawson steps up to the lectern in the crowded funeral chapel, an acoustic guitar across his chest. To his left, Napier lies in his beautiful bargain casket, the cherry wood no worse for the two years it spent in a van in the driveway. He had the interior customized to honor two things he loved: the United States military and the University of Kentucky Wildcats. Stacey sits right in front of the lectern. She barely knows anyone else is there as Dawson begins to sing.

“You’ve got to fight this fight,

You’ve got to live this life

One minute at a time.

You’ve got to laugh, and you’ve got to cry.

So don’t let a second pass,

Live every minute like it’s your last.

I’ve lived free, and I’ve lived wild,

But at the end of the day, I hope I made them proud.

I hope I made them proud.

I hope I made them proud.”

At the end of the day, Moody tells the assembled, “Randy belongs to all of us.”

This article originally appeared in the January 2016 issue of Louisville Magazine.

To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, please click here.