Update: River City Drumbeat will have a virtual cinematic release nationwide on Friday, Aug. 7. More information on screenings is available on the documentary's website.

In the summer of 2010, Zambia Nkrumah beckoned her husband, Edward “Nardie” White, to her bedside. Nearly two decades earlier, the pair had formed the River City Drum Corp, a program for Black youth. Now Nkrumah was dying from late-stage cancer.

The River City Drum Corp had been White’s life’s work, a calling, if an unexpected one, that had impacted the lives of hundreds of Black kids in west Louisville. Nkrumah knew he couldn’t imagine continuing without her.

“When I close my eyes,” she said to him, “you’re going to quit the Drum Corp, aren’t you?”

“Soon as you are gone, baby,” he admitted. “I’m gonna get in my car and I’m leaving this place. I don’t know where I’m going. I’m gonna shut it down.”

“No, you’re not,” she replied.

She made him promise.

River City Drum Corp founder Edward "Nardie" White (left) with his successor, Albert Shumake.

White, who is now 67, wears gray dreadlocks, colorful shirts and African necklaces. He recalls that critical crossroads for the group while discussing River City Drumbeat, a new documentary about the River City Drum Corp. The film follows White in 2016 and 2017 as he hands over the RCDC reins to successor Albert Shumake, who joined RCDC when he was eight years old and stayed for years.

Currently on a film-festival circuit, the documentary is bringing renewed attention to the Drum Corp, formed at the Parkland Boys & Girls Club in 1991. (River City Drumbeat, produced by Owsley Brown III, has postponed its Louisville premiere at the Palace as part of the Flyover Film Festival. See site for details on postponement.) RCDC teaches pipe and drumline percussion to boys and girls up to age 18, along with African cultural traditions and academic skills. The students, who must keep a 2.5 GPA, practice twice a week and attend a culture class twice a month. They travel for competitions as they grow older.

The film tells a story about the transformative power of arts and community against the backdrop of a disenfranchised, predominantly Black west Louisville, long saddled with higher rates of poverty, ill health, educational struggles and violence. Many of the kids come from single-parent homes that struggle financially and face barriers from under-resourced schools and low expectations, White says. “We give children a level playing field, and guess what?” White says. “The competition rises.”

The filmmakers — Marlon Johnson and co-director Anne Flatté — aren’t from Louisville, but both had worked on movies about music and community, including a web series about Louisville Orchestra conductor Teddy Abrams. Johnson says he connected with the subject partly because of his own participation in arts programs while growing up in the Liberty City neighborhood in Miami, Florida. “A place not unlike the West End,” he says.

Shumake, who is now 37 and director of RCDC, shows off the troupe’s power on a cold February night in the group’s base behind the Immaculate Heart of Mary Catholic Church in west Louisville. The building is part of the church complex, in a former rectory where nuns once lived. Wearing a self-knitted cap, several silver chains (one holding an Egyptian ankh, the hieroglyphic symbol representing life) and rings on all fingers of one hand, he pushes past a battered metal door in a hallway dotted with trophies, photos and a quilt with a patch reading, “Practice like you’ve never won, perform like you’ve never lost.”

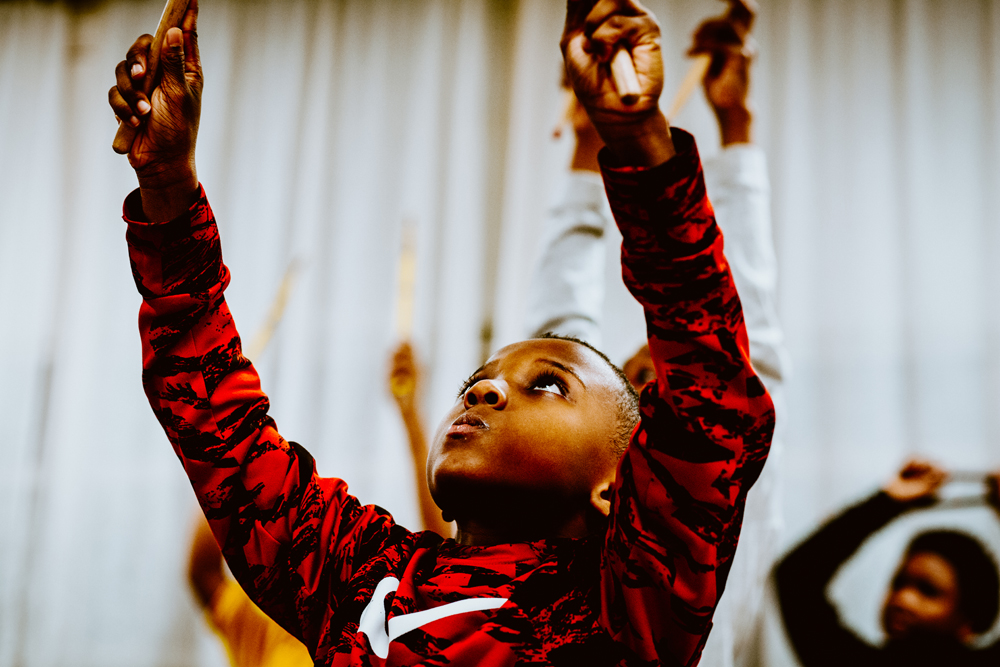

Shumake, sharing hellos and nods, carries a pair of drumsticks into a large room where nearly 30 elementary and middle-school students in tennis shoes and school sweatshirts form several rows. Before each kid stands a drum, many painted in African-themed green, yellow and red. The children made the drums themselves out of PVC piping, a rite of passage when starting the program. To do so, they stretch cowhides over the pipes with retaining rings made at Falls City Ironworks; the hooks and brackets are acquired from an Ace Hardware store at 26th and Market streets.

On this night, the children begin by reciting a call-and-response pledge, to their ancestors and families, to foster “a oneness in my soul, a healthy mind, a body strong, where the love might unfold.”

Shumake, among several adult leaders, shows a stern demeanor as he looks on like a general inspecting troops. “Y’all need to face front,” he says, looking at one child. “Square your body. Talking to you.”

Soon, Shumake is demonstrating a beat. “Boom. Boom-boom. Boom. Boom. Boom-boom,” he says. “Everybody!”

Drumsticks fly. Kids’ faces squeeze in concentration. The beat grows stronger, louder. It rises, tightens, then seems to loosen and begins to fall apart. “You lost your tempo,” Shumake says.

|

The beat rises again, the energy building as a big oil-barrel drum and cowbells kick in. Drumsticks pound. Bodies are unable to resist swaying. Some begin nodding back and forth with huge grins breaking out on their faces. A mysterious, cathartic force seems to have been loosed.

What is it about drumming? Shumake has a ready answer, which White reflects in the documentary: We are born into the world with this sound. “It’s the first song you hear in your mother’s womb,” White says in the film, referring to a mother’s heartbeat heard by a fetus.

Shumake says his path to lead the program began when he was eight and spent time at the Boys & Girls Club. He was like many of the kids in his Parkland neighborhood, but he also faced substance abuse at home and danger in the streets. Everybody else, it seemed to him, wanted to play basketball and football and listen to gangster rap. But he found his place playing drums and learning about African arts. “We played drums, ran around wearing African dashikis,” he says. “It created a safe haven for us alternative kids.” He says it instilled in him “a worldview bigger than the Gene Snyder Freeway.”

White, a former commercial photographer, had started working at the Boys & Girls Club, where he introduced a Kwanzaa program. That’s where he met his future wife, Zambia Nkrumah, a public school teacher. The Parkland Drum Corp, which later became RCDC, formed; she was educational director, White was director. (White and Nkrumah had been friends for years before they married in 1997.) “Zambia is the one who turned me on to the richness of African history and culture and, within that, drums,” White says in the film. “The children said, ‘That’s what we wanna do.’ From there it just kind of took off, and the whole art world opened up.”

Shumake says his experience with RCDC figured into his college essays. The group has helped spur many others to college, with White estimating that about half of participants at least attempt college. “I’ve got lawyers, I’ve got policemen, and I’ve got a guy who works at NASA,” White says.

Shumake, who has worked as a DJ and textile artist, was tapped to take over RCDC, perhaps because White said he saw a similar heart and love for art and empowerment. The two worked together for a time, with White tapering back his duties beginning in 2016 and ending his work by 2018. “It’s in good hands,” he says.

Once he began filming in 2016, Johnson and his crew came to Louisville on weekends for more than 18 months, followed by another year-plus of editing. But the first step was convincing the group that he and his associates were the right ones to tell their story. “The first time I met with Mr. White and Albert, we talked about our backgrounds, our worldviews,” Johnson says. “It was important that they felt like I was the right person.”

His crew soon became a regular presence that eventually faded into the background. “We’re in their homes, their places of worship. It’s about investing time, not rushing,” he says. “It’s about knowing when to allow the person to just tell their story. As time went on, they became more comfortable with us.”

River City Drumbeat, which follows the students through drumline battles like the Da’Ville Classic Drum Line Showcase, also shows RCDC members at home and at practice as they navigate the end of high school. In one scene, White visits the nationally lauded Louisville sculptor Ed Hamilton in his downtown studio. Hamilton talks to his friend and fellow arts leader about encouraging teachers from his past. “Somebody had to say, ‘You got something,’” Hamilton says to White. “That’s what you do.”

Peppered throughout are scenes of the West End, with its boarded-up properties and teddy bears marking the sites of homicides. The movie also notes how, in 2012, White’s 24-year-old granddaughter, Makeba Lee, was shot and killed near 32nd Street and Greenwood Avenue in the wake of another shootout that left her boyfriend and another young man dead. In the aftermath, the other man’s girlfriend allegedly walked up to Lee and shot her.

“Never in 100 years did I think I’d lose a granddaughter to violence,” White says in the film, bemoaning his inability to remove her from danger. “No matter what I tried.”

Although White pledged to keep going in 2010 after his wife died, he knew he couldn’t continue indefinitely serving as disciplinarian, cleric, teacher and mentor while constantly raising money to keep the nonprofit afloat. He moved from the couple’s three-story Southern Parkway home back to the small Portland home he still owned, where he lives among artwork, books and photographs. After about five years, he lured Shumake back from Lexington, where he’d been living since graduation from the University of Kentucky.

The children that Nkrumah had nurtured were moving on, and White believed he had contributed to what the African proverb that starts the film says: giving children both roots and wings.

“It was timely for me to come back and for him to pass it along,” Shumake says.

These days, White makes ceramic bowties and is converting a shed into an art workspace, while still teaching drum programs at a couple of middle schools.

The event at the Palace will include a post-screening celebration. That, White says, will be “the best going-away party I could ever have. I just wish my lovely wife was here to see it.

“She’ll be standing right beside me, saying, ‘Now you can quit.’”

This originally appeared in the March 2020 issue of Louisville Magazine under the headline “Sticking to It.” To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Photos by Mickie Winters, mickiewinters.com