By Betty Bayé

I expected my mom and Aunt Evelyn to be worn out after their long trip from New York to Louisville riding the Greyhound, aka “the dog.” On the contrary, Mom and her elder sister bounced off the bus like schoolgirls, excitedly going on about their lovely ride through the mountains. My aunt actually squealed with delight when she spied the Louisville Gardens sign; Aunt “Ebby” and Uncle Buss were huge fans of professional wrestling. I suspect all she knew about Louisville were the wrestling broadcasts from the Gardens; that Muhammad Ali was born here; and that her niece, that would be me, moved to Louisville from New York to be a newspaper reporter. That visit during the summer of 1986 was my mother’s first and last to Louisville. In fact, it was the farthest she would ever travel.

It was blazing hot the day Mom and Aunt Ebby arrived, so hot that the chocolate candy bar my aunt was holding melted in her hand. Even worse, my car’s air conditioning had gone out shortly before their arrival. Mercy! I hustled the VIPs to my house. My being the operative word because 2306 W. Chestnut St. in west Louisville’s Russell neighborhood was the first home I’d ever owned. I might have eventually become a homeowner had I remained in New York, but the greater likelihood is that, like the majority of New Yorkers, I would have been a lifelong renter.

|

| Bayé's Aunt Evelyn (left) and mother, Betty Jane Winston, with a school friend. |

My parents, George and Betty Winston, met in Harlem in 1944, and, in today’s parlance, they would have been classified as working poor. In the 1950s and ’60s, they worked hard, but homeownership wasn’t in the cards. My father worked as a trucker’s helper in Manhattan’s old Garment District. In early 1983, he wept and said to me, “Boopie Girl, I’ve never made more than $6,000 a year in my life.” This was the man who walked miles from East Harlem to his job downtown because he’d given me his 15-cent subway fare to buy a notebook for my stenography class at Benjamin Franklin High School. I was studying to become a secretary.

My mom was assistant to Mrs. Sarah Walton, the head cook in the daycare where my two younger sisters were enrolled. Mom’s job had significant perks. She could walk to work, so she didn’t need money for carfare. She could keep an eye on my pre-school-aged sisters throughout the day. Her job provided paid holidays and vacations and a retirement plan. My dad had no benefits. If he didn’t work, he didn’t get paid. The other significant benefit not formally included in Mom’s compensation package was the leftover milk, juice and food she brought home most evenings. A running joke was that if anyone ever asked What’s for dinner?, the Winstons could say, “Whatever the daycare served for lunch.” Working poor or not, my parents earned too much to qualify for public assistance or for us to receive free school lunch. But with three children to clothe and feed, there wasn’t money for such “luxuries” as owning a home or summer vacations. They didn’t own a telephone until I had graduated from high school in 1963.

So, doggone right, when my mom and aunt came to town, I couldn’t wait to show off my historic, all-brick, two-story, Federal-style townhouse, with its original pocket doors, three fireplaces, 12-foot-tall ceilings and two first-floor front windows nearly as tall as the ceilings.

Catherine Guest, my realtor, was a pioneering African-American entrepreneur. She and Joe Hammond, an influential businessman and namesake of the popular nightclub Joe’s Palm Room, were partners in the real estate business. I considered buying a house in the Zorn Avenue area where I was renting a condo, and Catherine showed me houses in Shively and the Shawnee and Chickasaw neighborhoods; they were traditional two-stories and ranches. But none captured my heart like 2306 W. Chestnut St. I fell in love at first sight. The townhouse sat far back from the street on a deep, narrow lot that had three buildings: the house itself, a cement garage and a cement storage shed. It even had a koi pond I never stocked and several nut- and fruit-bearing trees.

Built in 1880, my Chestnut Street house wasn’t technically a brownstone, but its tall exterior doors and narrow front windows reminded me of the classic brownstones I’d grown up admiring in Harlem and Brooklyn. A New York brownstone would have been unaffordable on a reporter’s salary, especially one that’s 100 years old and requires extra-special care. But in 1985 Louisville, I could afford the $39,000 asking price for the three-bedroom, with updates that included a guest bath with laundry and a closet off the master that was itself as large as a bedroom. My closet even had a window. One of the first things I did in my new house was to transform one of the upstairs bedrooms into a den. I had floor-to-ceiling bookshelves installed on either side of the fireplace. The carpenter made a small ladder I could climb to reach the books up high. The cozy den was where I hung out before bed, and on chilly winter nights I would fall asleep watching TV or reading.

A present-day photo of the West Chestnut Street home the author owned in the '80s and '90s. // by Joon Kim

Shortly after I moved in, Arnold Gibbons, my former professor at Hunter College in New York, came to visit. He and his wife owned a brownstone I adored in Brooklyn. I never dared to ask how much they paid for it; that would have been gauche. But when I shared with Arnold that I had made a $2,000 down payment for my Chestnut Street house, he was incredulous. “By god,” he said in his lilting Guyanese accent, “one can buy a house in Louisville with a f***king credit card!”

My house impressed Mom and Aunt Ebby, despite the steep steps to the second story. Looking back at old photos, it occurs to me that the furniture I brought with me from New York looked dollhouse-sized in those high-ceilinged rooms. In one photo, my six-foot-tall artificial Christmas tree looks like an unfed potted plant.

I showed Mom and Aunt Ebby around the newsroom, where the air was stinky and thick because so many editors and reporters, including me, smoked at our desks. The C-J and Louisville Times were at full strength then, so practically every desk chair had someone’s behind in it. From my car without air conditioning, I showed them City Hall, the Belle of Louisville, some parts of the West End and Bardstown Road. The bohemian vibe and general eclectic funkiness of Bardstown Road’s small shops and restaurants reminded me of New York’s Greenwich Village before it was de-funked and gentrified.

It was hell-hot in Louisville, and Mom and Aunt Ebby were eager to get back to my house, where the central air was humming. Aunt Ebby ventured out into my backyard one day and planted some flower seeds. I’m not a flower person, so I didn’t know then and don’t know now what variety those yellow flowers were. But they bloomed every year. It was a reminder of Aunt Ebby, but also of an African proverb about planting trees that one may not live long enough to sit under.

|

| The author with her dog, Spike Lee. |

I smile even now recollecting Mom and Aunt Ebby coming down the stairs each morning of their weeklong stay, toting shopping bags filled with their medicine, wigs and other incidentals they anticipated they might need during the course of the day. They weren’t about to climb those stairs again until time for bed. Plus they had me, the youngster, to climb up and down the steps to fetch whatever they might need. It was nice having family in town. Though Mom and I spoke just about every day, she would inevitably rush me off the phone because she didn’t want me to be saddled with sky-high long-distance bills. I got back to New York as often as I could afford, but after living in Louisville for two years, I really missed our meandering conversations. And her fried chicken and potato salad. I was not at all embarrassed about missing my mommy.

I missed my father too. He died in 1983, the year before I moved to Louisville. One of the many things my dad despised while growing up black in Richmond, Virginia, was, in his words, “all those damned Confederate statutes.” Some of the stories the Courier-Journal covered during my early years in town would have mortified my father. I wrote about the racially motivated firebombing of a black family’s home in southwest Jefferson County, and was assigned to cover the ensuing Ku Klux Klan rally. “Ms. Bayé, I can’t guarantee your safety,” a Klansman said during a chilling conversation that included him referring to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as Martin Luther Coon. I hung up the phone, went to the night editor and said, “The Klansman told me not to come. I suggest you send the biggest, whitest reporter we have.” In the mid-’80s, another big C-J story was the discovery of Klan members in the old Jefferson County police department.

This was the 1980s, not the 1880s.

I can just imagine my dad’s reaction, had I been able to tell him about my interview with big-band singer Rosemary Clooney one Kentucky Derby. I was taking notes on Millionaire’s Row at Churchill Downs and, as she talked, one of the guests (who was a little tipsy) crept up behind me, tapped me on the shoulder real hard and said, “We need drinks at table 14.” Clooney, to her credit, was embarrassed for me. “She’s a reporter, not a waitress!” she said.

My dad loved history and would have enjoyed chatting with my next-door neighbor, former state Rep. Mae Street Kidd, who lived for years on West Chestnut Street. The daughter of a black mother and an absent white father, Mrs. Kidd was born in 1904 east of Louisville in Millersburg, Kentucky. She was nearly six feet tall, had blond hair and was light-skinned enough to pass as white. She chose not to. Of her mixed race, her biographer Wade Hall, in his book Passing for Black: The Life and Careers of Mae Street Kidd, quoted her as saying, “I don’t mind my white blood — it’s an important part of who I am — but what’s more important is what I did with my life.” And she did a lot with her long life.

Mrs. Kidd was in her 60s when she entered politics. She had retired from successful careers in sales and public relations. She was a Democrat who didn’t suffer fools gladly. When I moved next door, she reminded me that, as a young black professional and resident of her street (which had been home to many fine, upstanding and accomplished negroes), I had to carry myself in a certain way. She said a West Chestnut Street address signified that one had arrived — or, at a minimum, was on the way up. I imagine that my being a reporter for the Courier-Journal gave me at least a little cachet, by her estimation. One day, however, I was on the large deck I had added to the house. Mrs. Kidd beckoned me over to the fence. She’d heard me speak somewhere and felt obliged to tell me that there were too many “ums” throughout my talk. I wasn’t even aware that I was frequently and audibly hesitating between thoughts. Mrs. Kidd was in her 80s, and I wasn’t about to get snarky with an elder. I simply said, “Thank you, Mae” — she let me call her that — “I’ll remember that the next time.”

Mrs. Kidd and her first husband, Horace Leon Street, purchased their home on Chestnut decades before I moved onto the block. She enchanted me with stories about the sundry black professionals — educators, doctors, lawyers, preachers, politicians, entrepreneurs and so forth — who once lived up and down Chestnut Street. Samuel Plato, the first black architect contracted to design U.S. post offices, resided on West Chestnut. She recollected how, to get ready for the Derby, she and some of the neighbors spruced up their yards and gardens and painted the tree trunks along the street white, to give Chestnut an even grander air. “It was beautiful,” she said, wistfully.

Mrs. Kidd told me about lavish parties and that out-of-town guests, including Martin Luther King Jr., held meetings and lodged with Chestnut Street’s residents. Such were the times that African-Americans — for all their talents, fame, professional accomplishments, fancy cars, and even money to burn — weren’t welcomed at segregated downtown hotels.

Mrs. Kidd’s Chestnut Street memories jibed with the reporting and research I did for a special 1989 Courier-Journal series on Louisville’s neighborhoods. She seemed to enjoy my company, though I suspect some of Mrs. Kidd’s visits were prompted by the handsome gentleman I was dating at the time. I believe that she had a little crush on Charles Douglas. One time, she noticed him on my deck, came over, sat down, crossed her legs and openly flirted. “Mae, you’re still a vamp,” I teased. She didn’t deny it.

Many of Louisville’s movers and shakers of the era beat paths to Mrs. Kidd’s. She was friends with state Sen. Georgia Powers, the first woman and first person of color elected to the Kentucky Senate. Kidd and Powers were a dynamic duo in Frankfort, lobbying for and sponsoring civil-rights and fair-housing bills designed to increase opportunities and the quality of life for black Kentuckians. Mrs. Kidd sponsored the bill calling for the Kentucky legislature, finally, to ratify the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution. The amendments abolished slavery, defined citizenship and granted all men the right to vote. Though largely a symbolic gesture in 1976, Kentucky’s failure to join the majority of states in repudiating America’s ugly past was a lingering stain that needed to be erased.

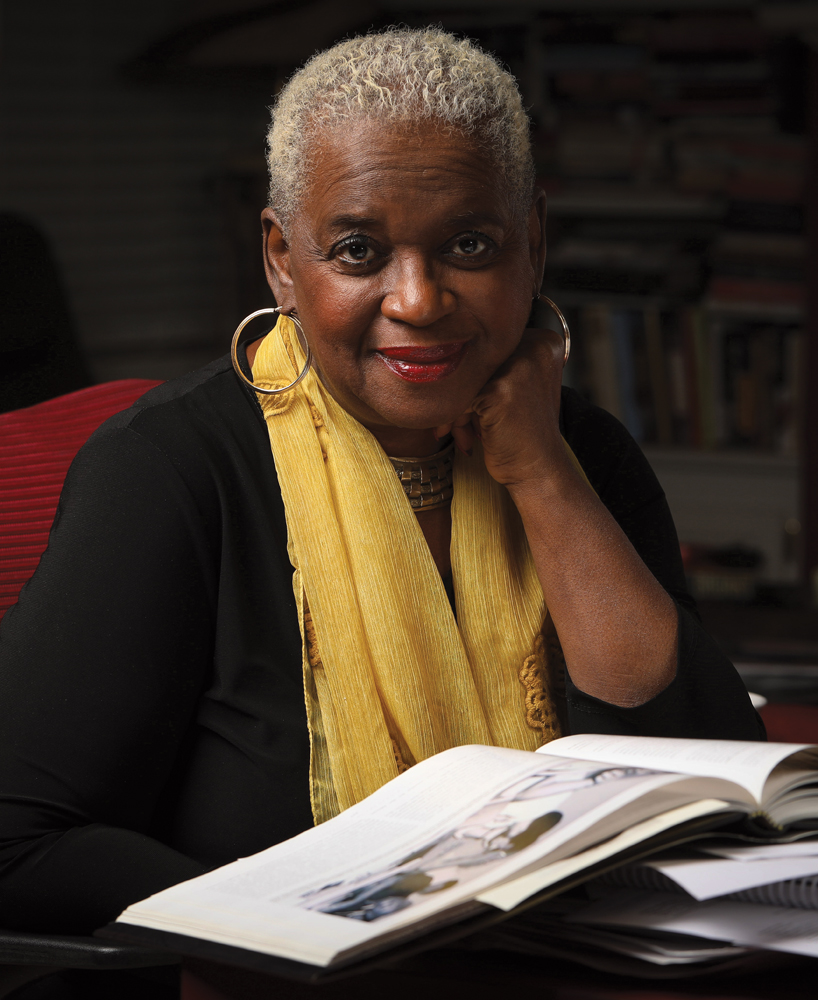

The author today. // by Joon Kim

Until I moved to Chestnut Street, I had never lived in a majority-black neighborhood. East Harlem and the Bronx were racially and ethnically diverse. Life had never before been just black and white. But I loved living in such a fabled neighborhood.

The old Quinn Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church building is boarded up now, but it was the jumping-off point for many local civil-rights demonstrations and meetings in the 1960s. Next door is the Chestnut Street YMCA, aka “the black folks’ Y.” The building, completed in 1914, was the original headquarters of the black Knights of Pythias Temple and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. The Y’s neighbor is the Western Branch of the public library, the first built expressly for African-Americans.

Central High School, for years Louisville’s only public high school for African-Americans, is at 11th and Chestnut streets. Plymouth Congregational Church, where Mrs. Kidd was a member, and its settlement house, which has served African-American kids in Russell for generations, is at 16th and Chestnut. Mount Lebanon Missionary Baptist Church, at 22nd and Chestnut, is where I finally got to experience the majestic preaching of Dr. Frederick G. Sampson II, who had moved to Detroit but returned to town to give a sermon. Midway through, I was stomping, waving my hands and doing a dance as Sampson expounded on the numeral one. Math had never before been interesting to me.

I have fond memories of Chestnut Street in the 1980s, of former neighbors. Rachel Goatley was an NAACP activist. Beverly and Sherman Morrow (a caterer and a police officer, respectively) lived next door to Mrs. Goatley. Educator Minor Daniels, for whom a JCPS school is now named, lived in the biggest house on the 2300 block with his wife Jessie, a grant writer. Chuck Cowan, a black belt and tower of power, lived across the street from me, which always made me feel safe. Beatrice McHenry, a retired educator who purchased and renovated the twin home attached to mine, kept me on my toes when it came to keeping up my side of the fence. It just so happened that one of her daughters, Susan McHenry, and I had become acquainted in New York when I freelanced for and hung out with the amazing women behind Essence magazine. Who knew I would end up living in Louisville and next door to her mom?

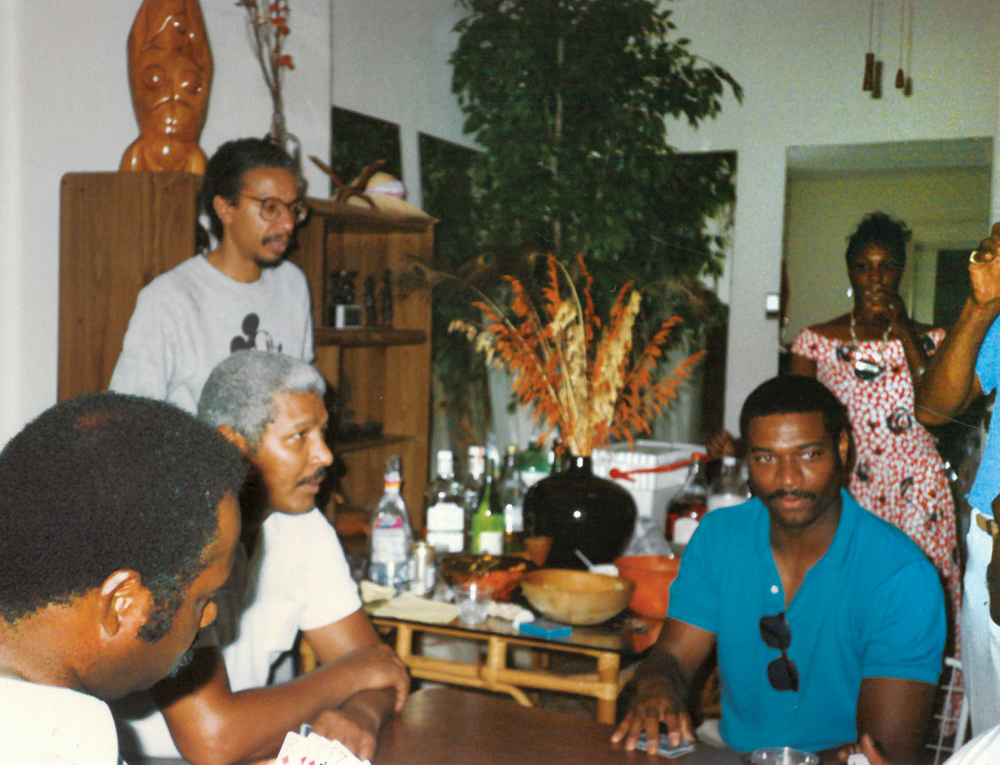

Friends (including sculptor Ed Hamilton, standing) at a party in the author's former home.

The city’s downtown hotels, restaurants and bars were desegregated when I moved to town, thank goodness, and many African-Americans could afford to dine and hang out after work. Many did, but black Louisvillians didn’t abandon their old haunts and habits in west Louisville. Come Sunday, many of the partygoers joined the elders, children and teetotalers by worshipping at their “home” churches. That wonderful cycle of black life in Louisville was largely unseen and unknown by outsiders, and it was new and exciting to me. Before I came to town, Old Walnut Street (now Muhammad Ali Boulevard) had been the cultural and economic hub of west Louisville, with its black-owned small businesses and vibrant nightlife. By the time I moved to Chestnut Street, urban renewal, aka “negro removal,” had eviscerated Walnut Street, but the good times still rolled west of Ninth Street in the ’80s.

Joe’s Palm Room, which retained the name long after Joe Hammond had sold the club, was where the powerful, the powerless and the curious converged to listen to live jazz, blues and R&B, have a few drinks, talk business and talk trash. It was a long and narrow space with a party room on one side and two levels of seating on the other. The top level was called a balcony, even though it was more like a two-step riser. Many people liked the balcony because they could observe who came and went. Musicians and singers practically performed on top of each other on a small raised stage up front. My favorite was Vic Frierson, who covered Luther Vandross’ music with the respect and reverence it deserved.

As is true at many churches, Joe’s regulars had preferred spots to sit. For example, I don’t drink, so I rarely took up space at the bar, which ran nearly the length of the club. I could be found most often sipping soda, smoking Marlboros and not conversing but conversating at one of the tables near the rear door closest to the parking lot and back patio. The after-work matinees at Joe’s featured live music, and if you didn’t get there by 5:30 you were liable to have to stand all evening. The place would be so packed some evenings that one had to say “excuse me” many times to get to and from the restrooms.

Club Cedar, which wasn’t nearly as fancy as the Palm Room, often catered to some of the same crowd. It sold delicious fried fish and chicken sandwiches from the window of a tiny kitchen. I ought to know how good the food was because I wasn’t doing much cooking at home. Club Cedar, only blocks from my house, was my go-to spot and could explain why I began packing on the pounds. On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, a lot of people who had ridden in the holiday motorcade through west Louisville would afterward ease on down to Club Cedar for free chicken wings.

Coming from New York, life west of Ninth Street felt like living in a small town within a small town. For a city of its size, Louisville had quite a few black journalists in the 1980s. It also had one of the most active chapters of the National Association of Black Journalists. Many journalists, black and white, eventually found their ways to the pool parties and barbecues at the Southwestern Parkway home of my C-J colleague Merv Aubespin.

|

| Friends hanging out in the side yard of the author's former home. |

One year, I managed to snag an invitation to Dr. Ralph and Lois Morris’ Kentucky Derby party, which I had heard was the Derby party. Most of the partygoers were much older than I was at the time. As I wound my way through the slivers of space between bodies and furniture, it was clear to me that Louisville’s pioneer black professionals sure loved to ball.

Bob Douglas, then a professor at the University of Louisville, and his wife Laura, an attorney, opened their home off Southwestern Parkway for Christmas Eve and Fourth of July parties. Bob’s running buddy Carman Weathers, an educator who loved to argue, would always lure someone into a heavy political debate that would end with him and his opponent standing shoulder to shoulder at the bar, exhausted and no closer to agreement. James “Stretch” Ealy was a tall, lanky, suspendered, funny-as-hell school security officer, and he would always crack us up. He was Louisville’s own Richard Pryor. At one party, a certain woman showed up with a certain man. Stretch, may he rest in peace, looked the woman up and down and, with a straight face, hollered over the din, “Damn, girl, you must be the loneliest woman in Louisville to be out with him.”

State Sen. Gerald Neal and his wife Kathy drew epic crowds to their annual backyard Derby parties over on Winnrose Way near Chickasaw Park. They’ve since turned the event into a scholarship fundraiser and moved the festivities to the Kentucky Center. But the Derby parties on Winnrose were magnets for politicos wanting to get up close and personal with their African-American constituents.

I threw a few parties at my house on Chestnut. My soirees tended to be informal and centered mostly on conversation, music and card games, especially bid whist. My sweet and thoughtful friend Charles Douglas, Bob’s younger brother who passed away last summer, colluded with my homegirl Lynette Taylor to pull off a surprise 40th birthday party for me at the house. They designed the cake to look like a newspaper.

I said yes when my hairstylist asked to have her wedding in my backyard. We erected a small tent on the deck, which is where the actual ceremony took place. We festooned the deck with crepe-paper streamers in her wedding colors, baby blue and white, and decorated the tables with matching paper tablecloths, napkins and centerpieces of white artificial flowers. We piped in music from speakers standing on the steps to the side door. It was a low-budget affair. The marriage didn’t last long, but my backyard never looked more beautiful.

I loved my house and I loved my life west of Ninth Street until some time in the mid-1990s. That’s when ill winds blew in, and my sweet Chestnut Street was in its path. Several of my elderly neighbors had fallen ill or passed on. Mrs. Kidd, bless her heart, had lost most of her vision by then, and other infirmities required her to leave the home she had meticulously taken care of for so long.

Hundred-year-old houses need a special kind of care that wasn’t forthcoming from the new players in the neighborhood, particularly the absentee landlords. An alarming number of Chestnut Street’s once-grand homes were abandoned, boarded up and sometimes set afire by squatters. Unscrupulous contractors, in the middle of the night, began to dump huge loads of construction debris in the alleys behind our homes, creating unsightly messes, inviting critters and blocking, sometimes for days, residents’ access to our driveways and garages.

Right before my eyes, the community I loved had become a dumping ground and was abandoned, it seemed to me, by everyone with the power to stop it. Eventually, I had the heartbreaking realization that the thrill was gone, and that I, too, would have to abandon the first home I ever owned. After 10 years, I reluctantly decided to put my Chestnut Street house up for sale in 1994. My decision included the fact that my mom and Aunt Ebby were right when they predicted the daily treks up and down the stairs would take a toll. After a year on the market, the house sold (for less than I had hoped), and I retreated to a single-level condo in the East End.

"I have fond memories of Chestnut Street in the 1980s, of former neighbors." // by Joon Kim

I’ve been following the news about the plans to revitalize parts of west Louisville, including the Russell neighborhood. My excitement is tempered by my fear of gentrification, my fear that the community I fell in love with — and where, as a young woman, I could afford to buy my first house and patronize black-owned small businesses — will gradually disappear.

I want to see Russell cleaned up and revitalized, but will the residents who’ve hung on through the lean years be forced out? Will they have a real say in what’s coming? Will they be allowed to move back when all is said and done? I fear gentrification because I have seen the heart and soul ripped out of the Harlem that I once knew and other black communities. I fear that outsiders will make all the major decisions, suck up the majority of the government and private-investment dollars, and then pitch pennies to the organizations and churches that never abandoned the West End. In a recent speech, Sadiqa Reynolds, president and CEO of the Louisville Urban League, said something that resonated: “We can’t only be focused on pretty buildings. Black ownership has to be a priority.”

I grew up in a public-housing project that was paradise compared with the slums my family had moved out of. I watched my mom and dad work hard but never earn enough to buy a house or even a car. They wanted the best for me, and I want the best for other African-Americans in Russell and other neighborhoods being eyed for revitalization. I want other African-Americans to experience the joy and the sense of accomplishment that I did 34 years ago, when I put a key into a lock, opened the door of my first house, stepped inside and said, “This is mine.”

Every now and then, I ride past my old house and recall the good times. Maybe one day I’ll get out of the car, knock on the door and ask the owner if I can look inside. I wonder if the flowers that Aunt Ebby planted are still blooming.

Betty Winston Bayé is the author of the forthcoming memoir The Book of David: An East Harlem Love Story.

This originally appeared in the March 2019 issue of Louisville Magazine under the headline "Sweet Chestnut Street." To read more from our 2019 West End Issue, click here.

To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Cover photo by Joon Kim, studiojoon.com