The buildings have nothing left to give. Half sit empty, awaiting demolition, awaiting what’s next. So archeological excavators claw. Brick and siding crumble, messily but obediently. The Beecher Terrace public-housing complex, built in 1941, is a 760-unit barracks-style development now long out of fashion and well-worn. Watch the methodical deconstruction and thoughts gallop forward — to the $264-million renovation of the site and revitalization of the surrounding Russell neighborhood. What will it all look like in five or 10 years?

Glance one block over, to the Old Walnut Street Park at Ninth Street and Muhammad Ali Boulevard. A bundle of hard hats and bright-orange safety vests busy themselves in the dirt — not just surface dirt but deep dirt, layers of dark brown, light brown and yellow brown, a tiramisu of silt, sand and clay. These workers are only preoccupied with the past. They are archeologists examining life before Beecher Terrace even existed, back into the mid-to-late 1800s and early 1900s, when the neighborhood was a dense cluster of Jewish, German and Irish immigrants alongside African-Americans, many of whom were established professionals, like the 25 black doctors, three black photographers and two black dentists who called Russell home in that era.

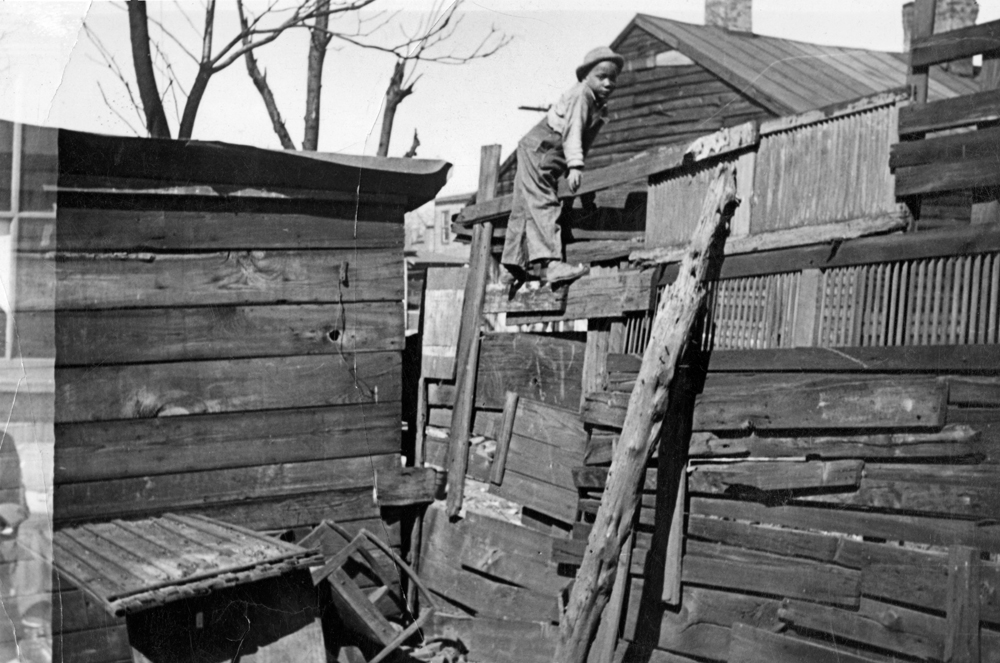

The Russell neighborhood in 1939, just before Beecher Terrace construction began.

When the city received a $30-million-dollar federal Choice Neighborhoods Implementation Grant in 2016, helping to kick-start the massive Russell project, part of the grant required a historical review of the land. Would planned construction damage historic elements, including artifacts below ground?

Enter Corn Island Archeology, a local team of veteran archeologists delighted to scoop at the earth, several shallow scrapes at a time with a trackhoe, as not to destroy anything precious. On the good days, trenches they’ve carved produce piles of dirt dotted with artifacts like porcelain dolls, pieces of ornate dishware (perhaps from a German household particular about their Victorian-era dining), pigeon bones likely tossed by a poor family ripping the meat for use in a stew, and toothbrushes made of hog’s hair and bone.

“We’re hoping we can tell the story about how these people lived,” says Anne Bader, principal investigator at Corn Island Archeology. “This is the biggest urban archeological project in Louisville.” The project will take a couple of years to complete. In a little more than one year, they’ve discovered more than 4,300 artifacts.

|

|

| Top: Jefferson and 12th streets following the 1890 tornado. Bottom: An 1890 photo showing the entrance to Baxter Square, where a park and community center are now located. |

In the early 1900s, the footprint of Beecher Terrace had about 380 individual lots. Corn Island (named for the now-submerged island near the Falls of the Ohio) will excavate only 23. And the group will focus on the back portion of the lot, where the outhouse or privy would have been located. Why? In an era without garbage collection, the toilet served as trashcan. “You wouldn’t believe some of the most amazing, beautiful things we find in the toilets,” Bader says. “Anything they couldn’t burn, they threw in the toilet. They were about 20 or 30 feet deep. You get this slow buildup over time of artifacts, kind of dated with the earliest stuff in the bottom.” (Let’s address the burning question: Yes, most of the waste has decomposed, but, as Bader says, “There’s a reason we call it night soil.” It’s dark, rich and occasionally a bit stinky.)

She has found one lot that had four privies on it, perhaps because as the neighborhood suffered from an economic crisis in the 1890s and affluent families started leaving for neighborhoods to the east, grand Italianate-style homes were divided into tenement housing or lots were split up. Several privies would’ve served multiple families, and, at the time, even the outhouses were segregated — blacks in one, whites in another.

Copious research determined the 23 lots Corn Island will sample. Maps, census records and every archived document Bader and her team could locate helped them choose, for instance, a lot belonging to Dr. Sarah Fitzbutler and her husband Dr. Henry Fitzbutler. Sarah became the first African-American woman to receive a medical degree in Kentucky, and her husband was Louisville’s first black physician. In 1888, he also opened the Louisville National Medical College, the only medical school in Louisville open to African-Americans at the time.

Archeologists have also pinpointed a section that once had a “female boarding house” or brothel on it; a lot belonging to Lithuanian immigrants; and one that was home to a black newspaper editor in the late 1880s. The Old Walnut Street Park site is Corn Island’s first stop, as it’s already clear of buildings and will be the first area developed as part of the Choice Neighborhoods project.

Most of what they’ve found so far is kitchen items — dishware, copper-alloy spoons, clay storage jars. When coins surface, Bader wonders if they were accidentally dropped into the outhouse’s deep, unforgiving pit. She marvels at intricate, hand-painted marbles and an almost-intact plastic mantilla hair comb that a century ago elegantly fastened a woman’s hair away from her face. At some point, she lifted it out of place. At some point, down it went, a few of the comb’s teeth either cracking off before, during or after its passage below ground.

Russell witnessed great change in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the Beecher Terrace footprint, businesses grew from 65 in 1884 to nearly 160 in 1920. In the late 1800s, most immigrants settling in the area came from Germany and Ireland, with a few from England. As the number of German and Irish households declined from 1900 to 1920, the percentage of immigrants from Eastern Europe and Russia rose. Bader says Russell was a diverse, eclectic area, a mix of working-class and upper-class white and African-American families.

In 1890, a tornado tore into Russell and then east through downtown. A few years later came a financial crisis, the worst in United States history at the time. It was the result of inflation, heavy farm debts and falling crop prices. In the spring of 1893, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad and the National Cordage Company, two of America’s largest employers, collapsed, setting off financial panic in banks and the stock market. Unemployment soared. More than 400 banks suspended operations as they struggled to meet withdrawal requests, selling assets and calling in loans, which resulted in the bankruptcy of more than 15,000 businesses.

Bader says that Russell grew into “one of the worst slums” in Louisville, blemished by poverty, residents packed into unsafe tenement housing. By the Great Depression, with so many working-class Americans out of a job, low-rent public housing surfaced as a way to help. In the early 1940s, Beecher Terrace was built for blacks and Clarksdale, in the Phoenix Hill neighborhood, was built for whites, at a combined cost of about $5 million. Both projects were lauded not only for addressing a housing issue but also for clearing out what had become notorious, dangerous neighborhoods. Down went the old, up went the two-story, boxy buildings that have now met their own expiration date.

Baxter Square, that’s one site within Beecher Terrace that will remain untouched as renovation occurs. It is home to a spray park, basketball courts and a community center, and Bader and her team were curious about the open, green space. In 1880, this park — Louisville’s first public park — was built atop Louisville’s first public burial ground. Bader wondered: Are gravesites still there?

According to an 1870 Courier-Journal article, relatives of those buried at the Baxter Square burial site had an option to relocate the deceased. The article reads: “Everybody in the city is aware that some years ago the remains of most persons buried there were removed . . . but for some cause there yet remains a number of aged time worn monuments and tombs marking the sleeping places of slumberers among the dead.”

Bader found other articles, one telling the story of young French immigrant lovers who fled to America in the late 1700s. Unable to marry due to political differences in their families, they created a life in Kentucky, supposedly surviving an attack by Native Americans but ultimately succumbing to some kind of illness. As the story goes, they were buried beneath elm trees that twisted together, and, during preparation of the site for the park in the late 1800s, their skeletons were found holding hands.

In late October, Corn Island archeologists found an old tin-type photograph from the 1860s. Upon putting a filter on the image, they were able to see the face of a former Russell resident staring back at them.

Last year, Bader and her team dug, finding 25 grave shafts. The city stopped using the site as a burial ground in the 1830s, Bader says, so it’s likely the interred are some of Louisville’s original settlers, dating back to the late 1700s. At Corn Island’s office in Jeffersontown, located (naturally) in a house that’s more than 200 years old, Bader saves a small chunk of a tombstone they collected. It belongs to a woman, maybe Isabel, maybe Mabel. Her full name, once etched in stone, has broken over time.

Every artifact Corn Island finds gets tenderly transported in a brown bag. In a dimly lit back room at their office, trays upon trays of history sit, most pieces scrubbed with a toothbrush and cleaned over a sink with a large, low belly and steady trickle of water. It’s painstaking work — the research, the trenches, the sifting of dirt, the sorting, the investigation of the historic worth of shards and fragments. “You can sit in a chair and read history, or you can be outside in the dirt and reveal history,” Bader says. “I prefer to reveal it.”

Eventually, some of the artifacts may land at the University of Louisville for further study or storage. Perhaps a Russell welcome center might want to showcase items someday. But that’s thinking too far ahead, to the Russell that will be, the one that exists mostly in the abstract. There’s so much hidden truth about this place yet to discover.

This originally appeared in the November 2018 issue of Louisville Magazine under the headline "Tossed and Found." To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Photos by Joon Kim, studiojoon.com