In late 1967, Ken Clay opened up the first black culture shop in Louisville at the corner of 28th Street and Greenwood Avenue, in Parkland. The Corner of Jazz, it was called. Posters of Malcom X and Muhammad Ali in the display windows enticed customers. Clay sold everything from music to jewelry to clothing to sculptures. He even rented the building from a black owner and got the inventory from black merchants across the country. It was a slice of pride — of hope.

Several months later on April 4, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, and places like D.C., Chicago and Baltimore broke out into chaos. Burning and looting bubbled up like a clogged sink, exposing dirty, neglected issues, like police brutality and discriminatory housing policies. In Louisville, though: Shock. Sadness. More grief than anger. King had spent time in Louisville. His brother A.D. was the pastor at Zion Baptist Church at 22nd and Walnut streets (now Muhammad Ali Boulevard), and families knew King, had books signed by him. Activist Sam Hawkins helped organize a group to go to King’s funeral in Atlanta. Hawkins had been a Southern Christian Leadership Conference staff member and founded the Black Unity League of Kentucky, which at first fought housing and police discrimination and pushed for better education and history in schools, and evolved to promote pride and the “black is beautiful” mantra.

Even before that rifle took King’s life, the Civil Rights movement had somewhat split on strategy — over whether nonviolence should be a principle or merely a tactic. In many activists’ minds, if the police were going to continue to be violent, there’d be pushback. “Black pride was rising,” Hawkins says, “and we were saying: OK, we’re not gonna just let you walk right over — those days are over with, the day of Jim Crow and all of that, where we bow down and say, ‘Yes, sir; no, sir.’ All of that’s over with.”

A month after King’s assassination, Manfred Reid got into a scuffle in Louisville with a police officer named Michael Clifford. Reid had intervened when it seemed Clifford was unjustly arresting Reid’s friend at a traffic stop, and Clifford started punching Reid in the face before arresting him. Clifford was suspended for excessive force. Weeks later, though, he got reinstated, and Louisville’s own boil surfaced, ready to pop at any moment.

Hawkins helped organize a rally at 28th and Greenwood, the same corner as Clay’s shop. The artery of 28th in Parkland had become a thriving replacement to Walnut Street, the black business and entertainment center closer to downtown that urban renewal had wiped out. Groceries, shoe stores, dry cleaners, butcher shops, record shops, banks, hardware stores, restaurants — Parkland had it all. By many accounts, it was on the up, even as white residents fled to southern and eastern parts of the county.

For the rally, on May 27, Hawkins had helped put Black Power leader Stokely Carmichael on the lineup. Hundreds showed up. Clay says that he had record sales that day. “It was as if they wanted souvenirs to show their friends that they had been there,” he recalls in a book he’s been writing.

District 5 councilwoman Cheri Bryant Hamilton, who since 2000 has represented parts of west Louisville, remembers that Monday well. It was her 18th birthday. Her senior prom had been the weekend before. Her mother, Ruth Bryant, was active in the community, and Hamilton went with her mother and grandmother to the rally that afternoon. Hawkins and some others stood atop a car and preached their gospel of justice and pride. But Carmichael didn’t show. According to Tracy K’Meyer’s book Civil Rights in the Gateway to the South: Louisville, Kentucky, 1945-1980, it was rumored that the FBI wouldn’t let his plane land. Others assert that the man who had claimed to be connected to Carmichael, James Cortez, was instead an FBI informant. Or maybe he was a fraud who didn’t even know Carmichael. Either way, the rally ended and the crowd began to disperse. Now, the chronology of events gets a little murky depending on the source, but here’s how Clay and others remember it. A young man had been sitting on the roof of Clay’s store to get a good view, and he threw an empty bottle on the ground. Hearing what sounded like a gunshot, an unmarked police cruiser muscled its way to the intersection. Officers had been waiting in the alleyways and side streets. Within moments, some in the crowd flipped the car over and set it ablaze. “I think it was a culmination of a lot of pent-up emotion and rage about King, about conditions, about housing, about jobs, about economics,” Hamilton says in her City Hall office, surrounded by posters of Obama, African art and the Dirt Bowl basketball tournament. “You know, it just exploded.”

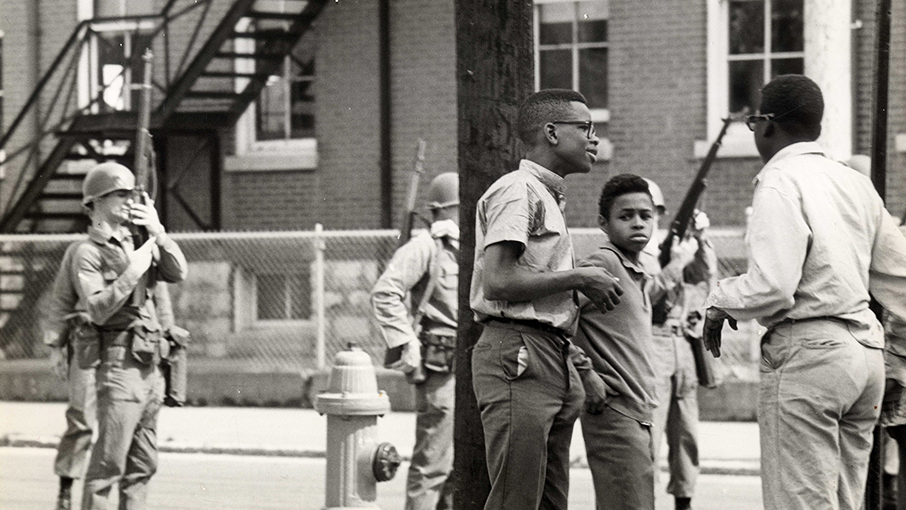

From there, angry youths turned to the businesses, looting and burning everything in their path. Hamilton and her family ran to find their car and leave the scene. By the following morning, the Kentucky National Guard had shown up with M14 rifles, on orders from Mayor Kenneth A. Schmied and Gov. Louie Nunn. This agitated the rioters even more, and more burning, looting and destruction occurred for several days. Hawkins remembers being in a pool hall and seeing people throw balls at officers. Clay went to check on his store and the guardsmen wouldn’t let him past their human barricade. He walked around a back way and some kids who were playing and throwing rocks made a loud thud, calling the attention of a guardsman who pointed his shotgun at Clay’s face, lowering it only when a friend of Clay’s from the mayor’s office came over to de-escalate the situation.

A branch manager at the Bank of Louisville packed up the bank’s assets and fled through the shattered front window as guardsmen patrolled the outside, according to the Courier Journal. The manager told the paper, “Right now, I’m washing my hands of the area.” He wasn’t the only one. The neighborhood that had already been bandaging its white-flight wound succumbed to full-on abandonment and disinvestment over the next five decades. Clay’s store closed about four months later.

Cortez, A.D. King and others got on WAVE, “urging people off the street for their own protection,” according to Civil Rights. White activists like Anne Braden and the Rev. Charles Tachau tried to negotiate with the city, according to the Courier Journal, calling for the mayor to come to the West End and appease the rioters and to meet some of their demands, such as firing Clifford, lifting the curfew that had been imposed and bettering the housing and schools in the black community.

By the end, according to Civil Rights, 472 were arrested. Fifty-two people were injured and two black teenagers were fatally shot. The neighborhood suffered 119 fires and $250,000 in damages. “A lot of people are not comfortable with the term ‘riots.’” Hamilton says, wincing at the word. “Disturbance.”

Soon after, Hawkins, Bryant, Cortez, Reid and two others, Robert Kuyu Sims and Walter “Pete” Cosby — all local leaders in the Civil Rights struggle — were arrested on conspiracy charges. Dubbed the Black Six, their trial went on for two years before they were acquitted. “People in the police department, on the inside, told us things,” Hawkins says, “so we knew that the city was trying to set up a situation where they were trying to get young black people — agitators like us — off the street.”

“I don’t think burning anything down accomplishes anything — because obviously we have not rebuilt,” says Hamilton, who once got thrown out of City Hall for demonstrations in ’67. “I think that’s one of the reasons why I got involved in politics — you can change more inside the system than outside the system, but then the two forces have to work together. You need that outside pressure and that inside know-how to accomplish what needs to be accomplished.”

In 50 years, though, not much has changed. Parkland development plans from the ’80s mirror those found on the city’s website today, both calling for shopping and food amenities, and access to jobs and better housing. The intersection remains deserted, with a weedy vacant lot and boarded-up buildings. It’s difficult to lay blame solely on the destruction that bled into early June 1968, as suburban developments like the malls were already sucking sales from the inner-city. “There was a Family Dollar on the corner and that closed down,” Hamilton says. In its place is the Arabian Federation Martial Arts Academy, which recently opened and is working to build respect, self-confidence and a sense of community pride among the dozens of kids it serves.

On May 27, Hamilton, Reid and Hawkins, along with State Sen. Gerald Neal and House Rep. Reginald Meeks, will gather at that somber corner for what Hamilton calls a commemorative dialogue. “People have to have hope and they have to have pride,” Hamilton says. “It bothers me so much when I see people littering, just throwing something out the window, just putting a mattress on the curb like somebody else is gonna pick it up — not taking responsibility for your neighborhood or the community. I think it has to come from within. Nobody’s gonna give that to you.” She says the neighborhood needs a lot of help. “It’s not about blame. A lot of white people today are like, ‘Well, I wasn’t alive back then, that was history, wasn’t my people or we didn’t own slaves’ — or whatever. OK, fine, well and good, but what are you gonna do now?”

This originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of Louisville Magazine on pg. 26 under the headline Unrest in the West. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Cover photo: Guardsmen patrol the Parkland neighborhood during unrest in 1968. // by George Beury, Beury Civil Rights Photograph Collection, the Filson Historical Society.