H&D BRASS POLISHING

2219 Frankfort Ave.

Damon Adkins, owner of H&D Brass Polishing, knows he buys too much — something every day. Pickers will call, talking about this fireplace piece or that pretty door hinge, and Adkins will add it to the room that glows gold when the sun shines through the windows. Quite the cluttered opulence here. Hundreds of candlesticks and chandeliers shimmer. On one wall, lamps are shelved floor to ceiling. Light fixtures have even been mounted to the front door of the showroom.

Despite the mess, Adkins knows exactly where the push plates are when an inquiring customer navigates the narrow path to the counter. To get there, the customer squeezes past Adkins’ wife, who’s at the tool-laden worktable unwiring a lamp before polishing. When Adkins’ son steps in to give him a break, he’ll sometimes call, say, “Dad, Ms. so-and-so is here and I can’t find her order….” Adkins will know it’s under the microwave or wherever. Adkins, now 56, was 15 when he began working at H&D Brass with his dad, who opened the shop in Clifton in 1979.

H&D owner Damon Adkins.

The opposite of the downstairs sheen is the upstairs polishing room, added on 25 years ago. Dust layers like thick wigs on the chandeliers. “Dust bunnies,” Adkins says. “All the dirt is from where the polishing wheel spits off dust when it licks a piece of metal. The dirtier, the better. Right, Victor?” Victor Bradley is his main man, has been with him about 17 years, the only non-family employee.

It’s like magic watching Adkins put a doorknob to the soft wheel, which turns at the humming command of the machine his dad built. One minute, the doorknob is dull and discolored, then it’s winking. Adkins learned all the ins and outs from his father, who polished in a factory beginning in 1949. Adkins knows to use a slower, less aggressive wheel on silver, because it’s more sensitive. Flimsier stuff demands polishing by hand. Real curvy stuff, too. When you’ve got texture on a piece — engraved flowers, for example — you’ve got to polish it in four different directions, to hit all the edges. He can lighten the dark, darken the light. His father also taught him how to weld. One day recently, Adkins wielded the welder his wife got him one Christmas and fixed 40 pieces that had piled up on the workbench, including a broken cowbell from a woman’s grandpa’s farm.

Adkins’ friends joke, “You make a living polishing brass? Really?” And the answer is, yes, he has his whole life. Only one in the city doing it. He gets orders from Florida, snowbirds wanting their brass kick plates shined before they return to Kentucky for Derby parties. One guy from New Jersey with 450 spittoons sends them eight at a time to be finished. Adkins once welded a finger back on a $250,000 statue for the Speed Art Museum. He has polished elevator doors. Distilleries make Adkins’ wife jump up and down when they ring: “Guess who called! Guess who called!” Last summer, Adkins, his son and Victor went to Woodford Reserve and cleaned up the 35-foot-tall copper stills top to bottom — especially the green buildup from a bad seal. Six days, $49,000. “We kicked our butts,” Adkins says.

A good life, but Adkins is ready to semi-retire. He doesn’t know if his son — who makes good money at Ford doing metal finishing (“Swear to God,” Adkins says) — will take over the business or not. Right now, he focuses on the small stuff. Like these medals. When a woman brought in her father’s ribbon-tattered WWII honors, they were solid green. You couldn’t even read the writing on the metal. But now, after Adkins has got his hands on the neglected pieces? “She’s probably going to cry,” he says. “Most do.”

KLEIN BROS. SAFE & LOCK

1101 W. Broadway

“My most cherished early memory of Klein Brothers is more of a feeling than an event,” says Robert Klein Jr., the owner of the locksmith business that has been in the family since 1914. It was a pride thing. Pride: How Robert Sr. would talk about working with his father and uncles at the lock shop after school at St. X and, later, after classes at U of L and after returning from the Navy. Pride: Junior coming in with Senior on Saturdays and filling the Coke machines out front or playing with the homemade lockpick his dad made for him. If Junior was lucky, they’d stop at Kupi’s Restaurant for breakfast on the way in. The only son, Junior was expected to work at the store — which he started doing at 15 — and eventually take over, which he did in 1991 at age 32. Klein, now 59, has “really narrowed down my job description.” He’s in and out of the shop on West Broadway, leaving the day-to-day to general manager Jaime Davidson, who has been with the business for 23 years. On a recent Tuesday, Davidson reviews some of the to-do’s: the safe work for a JayC grocery in Indiana, and the PNC Bank job, which is usually something like replacing a desk lock or changing out a keypad.

A typical day sees 25 or 30 jobs: basic lock changes, which can take about 45 minutes; rekeying a whole apartment building, which is a weeklong affair; fixing the locks on U-Scans, automatic doors or in the customer-service area at one of 200 Kroger locations, from Southern Illinois to Knoxville, Tennessee. Klein Bros. services all things doors in the Louisville Metro Government buildings. In high-traffic areas, the door closers (the elbow-like joint that pulls a door shut) abrade constantly. “Ever been to the Hall of Justice?” Davidson says. “Pretty hefty crowd. That door’s opened over 500 times a day.” They’ll replace those closers every 10 to 12 months, right down to the hinges. Sometimes they’ll drill open safes when a commercial customer forgets the combination, or when the police or FBI call, maybe six times a year. Davidson says one of the toughest jobs is when domestic violence leads to a lock change.

The front room of Klein Bros. stretches narrow but long. Rows and rows of blank keys — almost like shiny wallpaper — fill pegboard panels. Some are skeleton keys, which remind Davidson of the time 20 years ago when he had to pick a lock to save a two-year-old who’d trapped himself in a bathroom. He says the lock business is steady and knows it won’t go away. “People will always get fired,” he says. When that happens, Klein Bros. changes safe combinations, door locks. “Sooner or later, a house will get broken into, a business,” he says. “Crime is always going to be there.” It’s the lock mechanisms that might change. He sees trends on houses in the northeast U.S., like drill- and pick-resistant high-security locks. Technology advances, too. Davidson mentions retina scanners, and thumbprint readers, which Klein Bros. installed at Brown & Williamson Tobacco Co. in North Carolina.

“The mechanical part will never stop,” he says. “Things will always wear out.”

A-1 VACUUM

1523 Bardstown Road

A-1 co-owner Jimmy House

|

You name it, Jimmy House has pulled it out of a vacuum cleaner. Cat toys, socks, undies. “I’ve pulled dead mice out of there,” House says. He’ll wash the vacuums in a big tub of deodorizer in the “dirty workshop” at the back of A-1 Vacuum on Bardstown Road, where there are cabinets for pumps and wheels, rows of various-sized replacement belts, and, one day before Christmas, 29 vacuums waiting to be picked up. “People come in here all the time and say, ‘Clean my vacuum; it’s dirty,’” House says. “We’re working on other people’s dirt.”

His grandfather was a Kirby salesman in the 1950s and his grandmother started the business off the trade-ins. House’s father would fix them up in the garage and, in 1974, opened A-1 in the Highlands. When House was home sick from school, he’d go to the store and watch TV on the play mat behind his dad’s desk. As a teen, he’d ride his bike over from Hikes Point. Now Jimmy and Matt, the older brother who has worked at A-1 for 16 years, take turns running the shop. Dad, now 71 and an expert on vintage vacuums — like the one from 1918 in the store that doesn’t have any cords, just an air turbine that fills when you push it — works Thursdays to help catch up on labor and to keep himself motivated. Out front, he stacks a delivery of Bissells onto a dolly.

|

“A lot of people don’t think a vacuum store can stay in business, but we’re going strong. Our numbers go up every year,” Jimmy House says. “You know, Amazon can’t make a customer happy by repair, labor and customer service.”

As for the rest of the afternoon, maybe House will check out that vintage Shark steamer that came in. Maybe he’ll finish fixing the vacuum he’s checking for a bad motor; it looks like it’s undergoing open-heart surgery — its belt, brushes and wiring all exposed. Maybe he’ll update the company’s Facebook page, which the brothers keep lively with funny pictures, like the one of the Purina dog food bag somebody used as a vacuum bag, a hole in the back for the tube that sucks up dirt. Or the one of House’s newborn, sweetly swaddled next to a yellow Miele.

MAGNETIC TAPE RECORDER CO.

601 Baxter Ave.

Technician and tube specialist Barry McCullum inside Magnetic Tape Recorder Co.

This place has always amazed Charlie Green. In 1991, he used to sit in the empty lot across the street from the big brick building at the corner of Payne Street and Baxter Avenue with his Thermos of coffee and some doughnuts and watch people walk in and out of Magnetic Tape Recorder. He was jobless then, after the engraving company where he worked, a union shop, closed down. He’d gone back to tech school to learn computer electronics — a continuation of his high school education at Ahrens Trade School — but hadn’t found anything he liked. His father had always said, “If you learn electronics, Charlie, you’ll have work all your life.” And he did, minus Vietnam and those days in the vacant lot. He was handy with anything. Why not try stereo repair?

When Green bought Magnetic Tape from ready-to-retire Gene and Hazel Dillingham later that same year — selling his house and all his rental properties and moving above the showroom — the place was a mess of acquired stuff. When he told his grandma he was going to make the backroom storage, she said, “Charlie, are you going to live long enough?” Every night after closing up shop, he and his wife Marlene would carry boxes of record needles upstairs, sit on the floor and sort through thousands of them, labeling them while they watched TV. On weekends, they’d pull the blinds shut, organize the front room the best they could, Marlene forming a road map of the store in her head. After about three months, Marlene cuddled up next to Charlie and told him she didn’t want to go back to work at TGI Fridays, where she’d been a longtime waitress.

“But I don’t know nothing about running a store,” Marlene said.

“Did you know anything about waitressing when you started?” Charlie said.

“Well, no,” she said.

“You started off slow, now look at you!” he said. “We’ll find a way to make this work.”

Folks would bring in their Vietnam War-era turntables or ’70s speakers that were huge, thanks to what Magnetic Tapers call the “size wars” of the era, when everyone wanted monster receivers like the old wooden-cased Pioneer or a 60-pound Sony. They’d bring in those sleek rack speaker systems from the ’80s. Lots of repairs despite being the ’90s, when surround-sound home theaters were hot. For attorneys and doctors, Green worked on reel-to-reel dictation and transcription equipment, which used the magnetic tape that gives the business its name. Gene Dillingham wanted something that sounded hi-tech when he opened up shop in 1956.

In ’93 or ’94, in walked James Hall, a skinny boy in big teardrop glasses. “Hell, if you coulda seen a picture of him,” Green says. At first he just worked the counter, answering phones. As time passed, Green learned that Hall is a fix-it guy. Cars, toasters, anything. Hall has a mind for it. He’d sit in a cramped corner, work on Green’s old units. Then he moved on to fixing blown-out or dried-up capacitors for customers. Twenty years later and he’s still back here in the something-shoved-everywhere work area, clicking another part into his online shopping cart, like some aluminum heat sinks to keep transistors cool. Harder and harder to find parts these days. Still, Hall has his mass of service manuals, with their foldout diagrams that look like a city layout. He bought them from other stereo shops as they closed down. On this mid-December day, he hopes to work on a “delicate little motor” in a turntable.

Current owner of Magnetic Tape Recorder Co., Joseph Hanna.

Ben Smith has worked here for about five years. He’s traditionally a TV guy but has tinkered in everything: stereos, cordless phones, answering machines, tape decks, CD players, VCRs. Right now, he’s working on a Sony stereo for resale. Already cleaned all the controls, re-soldered weak connections inside the amplifier, replaced the memory capacitor. Moving to Magnetic Tape was a natural switch for Smith after he and his brother closed down their store, Bailey TV. He’s a member of LETA, the Louisville Electronic Technicians Association, which is how he met Green, who has just walked in from upstairs to pick up a package.

“I’ll miss the place,” says Green, now 70 and retired. His interest in the business started fading away several years ago when Marlene was diagnosed with cancer. He spent less time selling stuff on eBay to China, England, Ireland and places in South America, and more time with his wife, listening to her soft Irish music on KET. “I called it angel music,” Green says. He showed up at the shop less, handing the reins over to Hall. When Marlene died in 2012, Green considered closing the shop, one of the last of its kind in Kentucky. But there was something about this tradition, the novelty. People coming in with their father’s record player, wanting to, in a way, bring back Dad.

Some younger folks were interested in stereos older than themselves. Take Joseph Hanna, for example, the kid who came poking around in June 2013 talking about turntable motors and meters and volts. The kid who never stopped showing up. Green hired him part time, then full time, and, as of last year, Hanna — a U of L music major who has been buying records since he was 11 — owns the company. First things first, he’d like to get the business on the computer. “Everything we do is on pen and paper,” the 28-year-old says. “Which is endearing. People love that repair ticket. But it’s hell on organization. We’re always asking, ‘Where’s the ticket? Where’s the ticket? Does anyone have the ticket?’” Hanna never met Marlene but sees her writing on some of the old tickets. He’d also like to see some organization amid, as Green puts it, “60 years of stacking up.” The crew constantly digs through boxes in the store and the even messier warehouse next door. Sometimes they’ll find something magical: an old tube amp, or a mid-’50s amplifier Green bought at a yard sale for $20 and sold for $900 on eBay. Hanna wants this place as clean as the ’60s photos of original owner Gene Dillingham, pictured answering the phone while smoking a cigarette inside.

On this day, customers flow in and out. One talks about how “Doc” across the river just died, how Doc’s daughter is slowly but surely learning some of the repair work, so she can potentially continue the business. Hanna says, “If there were other people out there, we’d send folks to them.” Everything’s falling on Magnetic Tape now. Hanna disassembles a speaker for a customer. It needs a replacement tweeter — the part that filters higher notes through a speaker, the opposite of a woofer for bass. Hanna recently “worked his keister off” trying to talk a guy into giving him the sentimental speakers, everything dead but the tweeters. Hanna told him, “Look, if you leave these with me, they’ll save someone else’s stuff.” Kind of like being an organ donor.

As for Green, he won’t go far. He bought the duplex beside Magnetic Tape and has plans to “jack that sucker up 12 foot, put a garage under it, and make a house of it.” Says it’ll be the home he dies in, the last addition to what he calls “Charlieville.”

Hanna says, “Charlie World.”

Hall says, “Charliewood.”

WANG'S WATCH REPAIR

9310 New LaGrange Road

The door to the little white shed swings open and a young man walks into Charlie Wang’s time machine, clocks scattered over the plywood walls, watches overflowing shelves in the cases.

“Hi,” the man says. “I called you about my Rolex Submariner flaking.” He seems unsure of the somewhat smoky-smelling Wang’s Watch Repair, in Lyndon, which he found by reading online reviews like most newcomers. Wang takes the watch, puts it under his work lamp bent low and bright.

“Usually the dial doesn’t flake,” says Wang, who has been repairing watches since his broke 30 years ago and he couldn’t find anyone to fix it. It quickly became his thing. He’d buy broken ones to practice on — sort of like his version of tuition to school. Cheap ones, at first, then into the thousands of dollars. He’d talk to old watch people in town (though many are now retired or dead) and read books, learning how to remove rust from a piece, why watches give false readings, when to use what tiny screwdriver. How to spot a fake.

Watch whiz Charlie Wang at work.

“It’s fake watch!” Wang says. Frustrating — the fakes, the junk, the “cheapies.”

“That’d explain why I got a really good deal on it,” the guy says, a little awkwardly.

Wang knows how kids these days love that Submariner — popular, sporty, big, with a chapter ring that turns. They wear it for fashion, for looks, without understanding any of the complications — any function that exists in addition to telling time, like displaying the day and date. In the old days, people used watches practically. If you were a pilot, you’d buy the GMT watch with dual-time feature. If you were a diver, you’d get a watch with a chapter ring that registers when you go underwater. If you were a cook, you’d use a chronograph (think: stopwatch) to time the pie.

“It’s fake! Only real one never flakes out!” Wang says, popping the band apart, then using a baster-like contraption to clean the insides by pumping out air. “Yeah, this a Chinese movement that copied the Swiss model.”

“So, it’s a fake?”

“I know the watch very well,” Wang says. “You cannot lie to me.”

Wang doesn’t like working on the fake watches. His specialty is vintage pieces. Sometimes 300-year-old watches, like the early English pieces with the ivory, tortoiseshell, silver or gold cases, or the Swiss pocket watch with enamel inlay. Doesn’t see many of those here, though, because Louisville’s “the country.” Wang, 58, opened the shop 12 years ago, when he returned to Kentucky following a stint in his homeland of Taiwan. He’d moved there — and had a repair shop for 13 years — so his son could grow up in the culture.

Mostly he deals with the jewelry stores, like Merkley Kendrick, which has been around for 180-something years. Last night, he finished a couple watches, including an old pocket watch, for Merkley Kendrick. He was out here at two in the morning, rounding out his 14- or 15-hour workday, which also included fixing the Rolex, Omega and Timex sent in from Lexington. He’s waiting on a crystal for the piece on his desk that he’s already taken apart, put in solution, oiled and polished.

Wang’s pet squirrel rattles in its cage. The squirrel is Tom. Wang found him and a baby chipmunk, Jerry, in the backyard last summer. Tom and Jerry. He’ll sometimes play with them after he’s done working or watch them cuddle up together at night. “They’re buddies,” he says.

Right now, as he’s working the kid’s “Rolex,” another man walks in, this one shiny-shoed, his Lexus locked. The Rolex Yacht-Master he has worn on his wrist for 15 years sparkles.

Wang's pet squirrel, Tom. |

Wang, comfortable in his navy shirt, jeans and flip-flops, says, “So, what can I do for you, sir?”

He’s looking for a Rolex President.

“Oh, I have just one. Not a quick sale. The President model? On the second shelf,” Wang says, nodding toward the long glass case of watches upon watches, several with Mickey Mouse behind their glass faces, one with the moon, some bands blinging, others dulled, no movements ticking. “Most of mine are old. I don’t have modern watch.”

“Plenty of things here,” the man says, searching for the real Rolex. His eyes finally find the navy face of the vintage watch he’s after, new ones retailing for $40,000. This piece is from the ’70s — 18-karat gold then and now. “You know, oughta have a prize — someone comes in here and guesses how many watches…”

“I don’t even know,” Wang says, knowing that case is only some of them. “I have no time to figure it out. I buy watches every day on the internet.”

“Do you really?”

“It’s all I do.”

HEIMERDINGER'S CUTLERY CO.

4207 Shelbyville Road

Carl Heimerdinger sharpening a chef's knife.

Augustus Heimerdinger is a ghost on the wall. His portrait — the first in a line of family cutlers — fades in its frame. Augustus’ great-great-great grandson, Carl, who is 64 and now heads the cutlery, still doesn’t know how Augustus, whose dad was a tailor, got into the business of sharpening and manufacturing knives and scissors. No records. Carl just has the knowledge that Augustus married up near Cincinnati, got on a boat down the Ohio, traveled as far as the Falls, then planted his feet in Louisville and started Heimerdinger Cutlery Co. in 1861. The knife cut down the bloodline to Carl Heimerdinger. Apron on, gray mustache tips curling up, he is soft-spoken as he helps an old man salvage some knives that were a gift from a past employer.

Carl grew up in the store. His dad, Henry, would bring him in on Saturdays or during the summers. He wasn’t allowed to touch anything in the retail showcases, the surfaces of which he’d clean. This was back when the business was downtown, before urban renewal, before 1983, when Heimerdinger moved to its current location in St. Matthews. Eventually, there were barber clippers for Carl to work on. He’d tear them apart, figure out what was wrong. “There’re probably very few people in this part of the country that have more experience repairing and remanufacturing hair clippers,” says Carl, who tried engineering school for a couple years before deciding it wasn’t his bag. “You have to go several hundred miles away to find anything that closely resembles our shop,” he says. “It’s become almost a thing of the past.”

Presently, Carl sharpens a chef’s knife in the dim back room, split by a cluttered “pack rat” shelf into two sides: the “knife-sharpening department” and “scissor-sharpening department.” He has developed a following among Louisville chefs: Matt Weber at Uptown Cafe, Daniel Stage at the Louisville Country Club, Edward Lee. Carl holds the knife gently against the grinding belt as the old machine softly whirs. It runs on the same motor from when Carl was 12. His dad — a woodworker at heart — rebuilt its wood frame in the ’60s, and they’ve used it ever since. A carbon-steel cleaver causes sparks to fly at the grinding wheel. Carl sharpens in the mornings, rounds out orders in the afternoons, like for the stylist from New York who sent in her shears. Sometimes Carl finds so much nostalgia in this peaceful, solitary job: polishing then honing a grandmother’s sewing scissors, or that special knife she used for cutting chicken, or a grandfather’s pocket knife.

Sentimentality dulls in the throwaway age. He isn’t sure how much longer shops like his will be around. One of his favorite German suppliers has quit making several scissors. “Between living in a disposable society and finding enough skilled labor…” — he trails off. “It’s sad.” In Germany, you’d apprentice for three years for this job. Carl has no understudy. His daughter helps out some, has learned some of the sharpening tricks, but is happy with her job as a supervisor at Buca di Beppo. His wife Glenna, who co-runs the shop — the way Carl’s mom did with his dad — isn’t sure how much longer they’ll keep the storefront open. “If he decides to quit, it’ll be the end,” Glenna says. Carl will always sharpen, sure. He can take that with him. Really, the two have been wanting to travel. They want to go to Germany, get to their German roots, visit Carl’s family in Göppingen. And Solingen, where all the good knives and scissors are made.

ROUNDHOUSE ELECTRIC TRAINS

4870 Brownsboro Center

Kevin Cook was five years old in the late 1950s, riding on the Pennsylvania Railroad, wide-eyed as the train slowly inched toward another engine coming from the rail yard’s side track. The engineer on board saw the wonder mixed with panic in the boy’s blue eyes, said, “Do you want to pull the brake?” Without hesitation, the boy stopped the train so fast that everybody ended up against the wall. Cook’s dad — a brakeman and conductor, like his dad had been, and his dad’s dad — yelled: “Don’t you ever big-hole it without telling someone first!” Big-hole — to lose all air in the automatic brake valve in an emergency stop.

By then, Cook already had a toy train, an “HO” scale set. (HO is the most common train model size.) He was so obsessed with it that he broke it trying to pull it off a shelf one day. At age eight, he used a ping-pong table to build a 5-by-10-foot layout with houses and trees, wiring his own switches so one train would stop at a cross while another passed. A couple years later, he was back on a real train with his dad, two brothers and great-uncle, who was in charge of the line running from Orrville to Columbus, Ohio, where Cook grew up. Cook was part of his uncle’s impromptu crew when the pickup call came from Killbuck. He’ll never forget pulling the throttle that day, even if it only upped the speed to 15 miles per hour in the slow zone.

Roundhouse owner Kevin Cook.

At 14, it took him six months of payments to buy a miniature brass engine. He disassembled it the first night he had it, its pieces spread on his dad’s workbench, his mother in dismay until he had it all back together hours later. As a transportation major at Kent State, he wrote his thesis on railway transport versus ground transport, about how the friction of a steel wheel on a rail is much more efficient than a rubber tire on asphalt. Books like Trains of the Old West amassed in Cook’s collection, now displayed in a room at Roundhouse Electric Trains, which opened in Windy Hills in 1983, and which Cook has frequented for parts for forever and has owned for eight years.

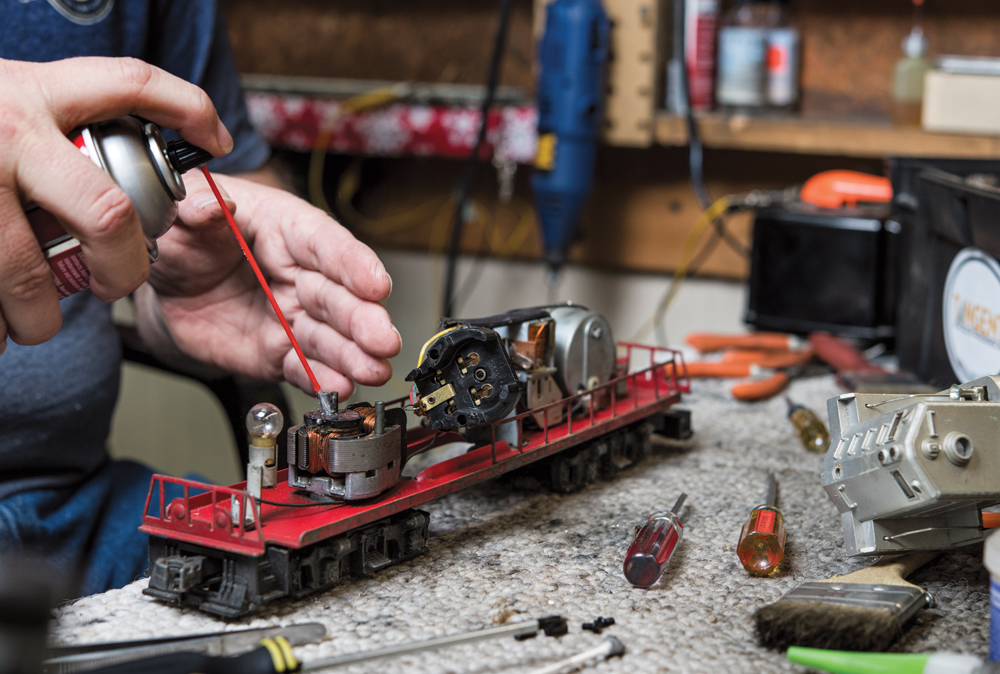

When Cook bought the place in the Brownsboro Road Shopping Center from founder Tom Bundiak — who has a photographic memory when it comes to postwar Lionel model trains, and who can fix a train before most people can diagnose what’s wrong — three other shops like it still existed in town. “We’re the last man standing,” says Cook, 64. He didn’t know then that it’d grow into 10 rooms that unfold like a maze. One room contains stuff to build scenes: fake trees, old warehouses, little cars with working headlights and taillights, tiny people, a sheep. In another: pre-WWII vintage trains and G trains — the big ones that can run outside. Cook throws out a bunch of fractions, says, “If you do your math right, you know that the HO is 1/512th of a G-gauge.” In a garage next door, the crew — including Bundiak and a rotating cast of usually retired 50-somethings who want a hobby — builds layouts. The main room has $1,400 locomotives, aka big steamers, like the CSX model that resembles the train that rolls from Frankfort to Louisville during Derby, and the beloved L&N model.

In the office, some repairs wait to be picked up. Some trains just needed a “C&L” — clean and lube — while others had wheels replaced. Some light bulbs — marble size, pearl size, down to peppercorn size — burned out, were swapped out. The crew replaces lots of couplers, those pieces that fit the train cars together; kids often bang them together.

“Working with trains teaches you so many things,” Cook says. “The wiring, mechanical engineering. The form, fit and feel of how things go together. How to work with your hands and tools. Game Boys and Xbox don’t help anybody.

“I call it therapy. You get to build your own world that works here the way you want it to. At your own speed. The real world is pretty messed up at times, but this is a retreat.”

LANE & EDWARDS VIOLINS

315 Wallace Ave.

Master luthier Matt Lane inside Lane & Edwards Violins.

“Bass-neck destruction!” Matt Lane shouts as a man enters Lane & Edwards Violins, the luthier shop that resembles the inside of a shiny wooden heart. The top part of the customer’s black nylon upright bass case is flopped over, sadly drooping. Lane looks at the instrument in its two pieces and knows right off that it’ll be a fairly simple repair. The neck broke clean off the body. Best to reattach it tightly with a lag screw through the heel, at an angle. Some Gorilla Glue, too. The bass joins the lineup of broken instruments leaning against country-kitchen-looking display cases, which Lane salvaged from a closed candy shop next to what was Lynn’s Paradise Cafe.

|

Lane has seen instruments arrive in pieces. Like that very sad child’s cello, which had been left behind the family car before it pulled out of the driveway. “A jigsaw puzzle with splinters,” Lane says. Or the violin that came in disassembled, saved from the rising waters of the 1937 Flood by a family’s grandmother. It was only missing one rib (the side plank of the instrument). “We heard that violin play for the first time in 70 years or more,” Lane says.

This was back at Mark Edwards’ shop in Fern Creek, which opened in 1973. Lane worked there for a dozen years before opening his own spot in St. Matthews in 2004. Edwards taught Lane, now 35, how to set a sound post, a small peg that goes inside a violin’s F-hole. Lane learned the Renaissance-era geometry associated with fixing a cello’s 77 different parts. Learned to tell when an instrument was made correctly or badly — of good maple and spruce, or cheap plywood or softer-grade hardwood. He saw how weather warps wood, how high humidity loosens the water-based glue that holds violin plates in place, how winter’s cold cracks contracting wood.

In the store, Lane is wearing his “Game of Strings” T-shirt (in the Thrones font). A teenage girl plays a concerto on a cello as Lane sands down another cello. He works gently, as if it were his own instrument. The girl’s dad will either buy her the one at Lane’s fingertips (used but with good maple) or the one at her fingertips (more expensive but with a deep resonance she’s already fallen in love with). The space where Lane works at the back of the shop is a collection of clamps, woodcarving tools and jars of varnishes. He inherited most of the tools from Edwards, who back in the day inherited some of them from a Louisville Orchestra retiree. A line of violins drapes across the back wall like a garland — some as small as six inches stern-to-stem for the two- and three-year-old players. They look like toys for teddy bears. The shop is also a repair vendor for JCPS and private schools such as Collegiate and Sacred Heart.

|

At 66, Edwards — who learned from the “cantankerous old man” at now-closed Shackleton’s downtown — is retired but still works every day because he wants to. He does nothing but restring bows in his corner. He’ll pull strands of Mongolian horsehair hanging nearby like a fat tail. He likes the hair to be strong, elastic, not too smooth. Only way to re-hair a bow is by hand. One hundred and sixty-two hairs per bow, and Edwards works fast. He taught himself this traditionally closely guarded secret. He’d dissect bows, see how the hairs lay over the wedges and angles. He has worked on a Tourte, which he describes as “the godfather of all bow makers.” He has worked on the famous Dutch violinist Michel Samson’s $500,000 17th- and 18th-century bows, Samson standing beside him as he did it, afterward saying: “Vonderful, you’re only one of two people in the world who can do this.”

“Sometimes I get goosebumps when I pick up a violin,” Edwards says. The quality, the history. Some made in the 1600s, 1700s. You look inside and find all of these repair labels. Paris, Budapest. Instruments that have traveled around the world. Sometimes with gypsies. It’s like that movie The Red Violin. “Then you put in your label and, 100 years from now, someone will read Louisville, Kentucky,” he says. “And they’re in Moscow or who knows.”

This originally appeared in the February 2019 issue of Louisville Magazine under the headline "The Fixers." To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Photos by Andrew Hyslop

Cover photo: H&D Brass owner Damon Adkins