This story originally appeared in the April 2007 issue of Louisville Magazine. Click here to subscribe.

The gravestone is simple. It's not a detailed statue depicting a Thoroughbred extended into full stride. A famous quotation isn't chiseled into its surface. Flowers don't even decorate the snow-covered ground in front of it. It merely displays a horse's name and the years he lived: SECRETARIAT 1970-1989.

*

It’s a cold February morning and Tony Battaglia, one of five stallion men at Claiborne Farm in Paris, Ky., steps through an opening in the shrubbery at the horse graveyard's entrance. Winter has tightened its icy grip and snow hides the L-shaped, gravel pathway that cuts through the cemetery. The sun glows behind a hazy sky like a dull spotlight. Each tombstone is basically the same, although moss sprouts from those dated before 1977. As Battaglia passes each headstone — BOLD RULER 1954-1971; PRINCEQUILLO 1940-1964; RIVA RIDGE 1969-1985 — he rambles off a why-this-was-a-great-horse story. Secretariat, who won the 1973 Triple Crown, is one of the 20 buried behind Claiborne's main office and one of five whose bodies are whole. (The tradition is to inter only a horse's head, heart and legs, so to be buried in entirety is considered the ultimate honor.) In front of Secretariat's grave Battaglia uses the fewest words: "We'll never breed another Secretariat."

*

The elevator’s doors slide open, and Helen "Penny" Chenery, who owned Secretariat and 1972 Kentucky Derby and Belmont Stakes winner Riva Ridge, steps onto the third floor's green carpet. She has just finished dinner (a lamb chop and mashed potatoes), dessert (warm apple pie and vanilla ice cream) and a glass of Pinot Grigio in The Academy's dining room. Its brochure calls The Academy, in Boulder, Colo., a "boutique retirement community," but Chenery insists that it's "an apartment with a really good restaurant downstairs." She turned 85 on Jan. 27, and one memorable birthday gift was a poem from her youngest child John titled The Ballad of Henny Pen (an Epic Doggerel). As Chenery travels down the hallway toward her apartment, the standout line is, "To the challenge you rose."

"I don't use a cane because a cane is a nuisance," she says, fixing her eyes straight ahead. "As long as I look forward and swing my arms back and forth, I can walk and not wobble." She moves past the reupholstered, cushioned chair. Past the grandfather clock. Past the picture of the magnolias. She makes it past all the other apartment doors and into her place at the end of the hallway, without grasping the handrail and without teetering. The apartment is spacious, with a kitchen, television room, master bedroom and main room that has five windows, three of which peer out at the Flatirons rock formations to the south. Although it's getting late and the day trip she made to Denver has worn her out, Chenery wants to do something before going to bed.

"I don't know where I hid the key," she says as she rummages through a few cabinets. Eventually, she pulls from a drawer a keychain that's shaped like the outline of a horse's head. "I had to ask permission to put a lock on this door," she says. As she opens the closet, it's clear why it's nicknamed her "treasure chest."

The halter of Somethingroyal, Secretariat's dam, hangs in there, as does Riva Ridge's. In the shadows rests a mahogany box that, when opened, reveals Riva Ridge's gold 1972 Derby trophy. Two cardboard boxes stacked on the floor are stuffed with memorabilia, items that trigger memories of the years Chenery has dedicated to horse racing. There are editions of Sports Illustrated and Time with Secretariat on the cover, both dated June 11, 1973, two days after his Triple Crown victory. Dozens of black-and-white photographs capture Chenery, trainer Lucien Laurin and jockey Ron Turcotte. A matchbook reads, "The President and Mrs. Ford." There's a datebook that Chenery once scribbled all over. Hair appointments. Luncheons. The Kentucky Derby. Her June 9, 1973, penciled note reads, '"Sec Wins Belmont 2:24 Flat Triple Crown."

“I just didn't want to put this stuff in storage," Chenery says. "This is my life."

It's been 34 years since Secretariat, the chestnut colt with three white feet, by Bold Ruler out of Somethingroyal, stormed to his historic 31-length Belmont victory to become the first horse to take the Triple Crown since Citation in 1948. Secretariat's time at the Derby (1:59 2/5) and Belmont are still standing records, and many consider his official Preakness time (1:54 2/5) inaccurate given that two Daily Racing Form clockers timed him running what would have been a record finish. Secretariat was named U.S. Horse of the Year in 1972 and '73, and he's still earning awards postmortem. On May 2, the horse will be inducted into the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame, marking the first time an animal will achieve the honor.

"He's one of those horses where you'd look at him and he'd just take your breath away," says Billy Reed, who spent much of his career writing about horse racing at the Courier-Journal, the Lexington Herald-Leader and Sports Illustrated. "I watch that (Belmont) victory, and I still get goosebumps."

*

The horse was foaled just past midnight on March 30, 1970. It was late, so Howard Gentry, Meadow Stable's manager, decided to hold off on calling Chenery until morning. When he did contact her, he said, "You’ve got a great-looking, big chestnut colt from Somethingroyal. " Chenery wasn't particularly excited on the telephone or when she traveled to Virginia the next week and saw the foal. "I just thought, 'He is too pretty to be any good,’" she recalls.

*

By the 1950s, Chenery's father, Christopher Chenery, had transformed The Meadow, more than 3,000 acres of land in Doswell, Va., into a horse racing powerhouse. He owned and bred 1950's second-place Derby finisher Hill Prince and 1959's third-place finisher (and Riva Ridge's sire) First Landing. From 1951 to 1960, the horses from what became known as Meadow Stable won more than 200 races and raked in more than $2.5 million. But by the late 1960s, Christopher Chenery wasn't thinking as clearly as he once had. What today we would call Alzheimer's was crippling his judgment. When he sold four of his most valuable broodmares for $40,000 apiece, the decision worried those closest to him. Some thought his declining health would eventually force the Chenerys to sell the farm.

Penny, his youngest child, who at the time had the married name Penny Tweedy, was a housewife in Boulder raising four children when her father was admitted to a hospital with an acute kidney condition in 1968. It was where he'd live out the rest of his days until he died in 1973, before Secretariat won the Triple Crown. The Meadow's board held an emergency meeting in 1968 and selected Penny to take over. Sure, she'd been riding since she was five years old and had been attending board meetings four times a year, but was she ready for this?

"I was doing diapers and meals," she recalls. "I was a wife and mother doing what I was supposed to do. I was playing the acceptable role. I didn't have any personal ambitions. It didn't occur to me that I'd have a career.

"But I knew that, of (his three) children, I had been groomed to succeed Dad. So I just thought, ‘Well, there's a lot to do here, but this is what I'm supposed to do.’ I really didn't doubt myself."

As a child, Chenery and her family (which also included her mother Helen, brother Hollis and sister Margaret) lived in a Tudor-style, granite mansion in Pelham Manor, N.Y., a suburb that was a "28-minute train ride" from Grand Central Station. In the 1880s, just north of Richmond, Va., her father grew up impoverished, having to go barefoot in the summer to save shoe leather. He swore his family would not do the same and became a successful public utilities executive. "We were probably one of the wealthiest families in this small town, and that sets you apart a little bit," Chenery says. "During the Depression, everybody still needs water and gas and light. So we didn't suffer. I was young, but I remember I was the only one in the class who got new dresses."

Christopher Chenery had been fond of horses as a boy and while Hollis or Margaret didn't follow in his footsteps, the youngest child, a "daddy's girl," gravitated toward his interests. She spent most Saturdays and Sunday mornings on horseback or watching her father's fox hunts and polo matches. In the mid-1930s, her father purchased back The Meadow, which his cousin had lost in 1922 because of financial troubles. While he replenished the dilapidated land and built stables and a home, Penny attended Madeira School in nearby Fairfax, Va., and then Smith College. As Meadow Stable started producing competitive Thoroughbreds, Chenery was involved only as a board member — she worked for a naval architectural firm that built the Normandy invasion's landing craft; joined the Red Cross in France, where she served soldiers doughnuts and coffee; attended Columbia University's business school; and married Jack Tweedy, a Columbia law student. They moved to Boulder, and by 1950 she was pregnant with the first of their four children.

*

Chenery needed a horse-racing crash course when she took charge of Meadow Stable. To familiarize herself with the business, she studied The Blood-Horse, Thoroughbred Record and Daily Racing Form cover to cover, trying to absorb as much information as her brain could soak up. She also met with Bull Hancock, who owned Claiborne Farm and had been one of her father's close friends. Living in Boulder, Chenery got Bluegrass updates about three times a week from secretary and family friend Elizabeth Ham. She also took monthly trips to the Virginia farm, supervised breeding plans and, in the beginning, followed her father's blueprint. He had been breeding his older mares to First Landing. That's why Iberia went to First Landing, a match that created Riva Ridge. Her father had also formed a deal with Ogden Phipps, owner of Bold Ruler, at Claiborne. So Chenery sent Somethingroyal to Bold Ruler, the result being Secretariat.

As Chenery immersed herself in the sport and began learning its intricacies — How often should this horse race? How long does it take this horse to recover from injury? — she obtained the confidence needed to have the final word. "I think I was able to achieve things that helped women in their quest for acceptance as functioning individuals in the business world or in the sporting world," she says. "The industry is a very old-fashioned one, and they didn't like having a woman in charge. . . . I did, when I had to, go in and say, ‘This is what's going to happen.’"

She carried that attitude when dealing with Casey Hayes, her father's longtime trainer. Few horse farms today breed and also race their progeny, but Meadow Stable was among the group that did in the '70s, which meant the training track was as important as the breeding shed. Chenery didn't trust Hayes, didn't like how he overworked the horses, didn't like how easily he went along with the broodmare sales her father made for $40,000 each. Although Meadow Stable was struggling financially for the first time in years, it had turned into an enough-is-enough situation. "At first I had to restrain him because he was pushing our horses too hard," Chenery says. "The biggest thing that I did was to fire Casey and to hire Roger Laurin and then, when he left, to hire his father Lucien" in 1971.

Although Secretariat had entered training while his elder, Riva Ridge, "saved the farm" financially as a champion two-year-old and a Derby and Belmont winner, Chenery didn't expect much from her chestnut colt. "When Secretariat was training, Lucien said, ‘Your big Bold Ruler colt don't show me nothin’. He can't outrun a fat man.’" Secretariat's first race, a maiden at New York's Aqueduct Racetrack, came a few weeks after Riva Ridge's Belmont victory. The future Triple Crown winner finished fourth, and Laurin launched a chair across the box seat. That uncharacteristic behavior signaled to Chenery that her trainer expected more from the colt.

"It surprised me because Lucien had not told me what he really thought," she says. "It was then I started to pay close attention, because Lucien knew how to lose — 'You win some; you lose some.' But the explosive reaction really surprised me. I said, ‘Maybe I need to take another look at this horse.’"

Secretariat went on to become U.S. Horse of the Year as a two-year-old, and by his Derby morning, the media swarm buzzing around Chenery was thicker than it had been the year before. She was now a well-known figure in the horse-racing world, a spokeswoman who was always smiling and fielding questions. "Secretariat would have been a different story without Penny," says Ed Siegenfeld, Triple Crown Productions' executive vice president. "Penny was the bright, attractive, articulate, sparkling woman in front of the camera. Penny was the thing that put it over the top."

Chenery says the timing was right, for her and her horse. "It was the time of Watergate and Vietnam, and here was this red, white and blue hero. He wore blue and white blinkers and was a bright red horse," she says. "Riva won two out of three and Secretariat was a far stronger horse than Riva."

By mid-afternoon of Derby Day 1973, Chenery had already spoken to everybody she knew. But there's only so much idle chatter one can handle; then it's wristwatch-glancing and trips to the ladies room until race time. "When you have something as extraordinary as Secretariat, you want to keep up a game face for the public," she says. "But inside you're really very tense, and nobody else really understands how you feel except the trainer. So Lucien and I got to be very good friends."

Secretariat unraveled the tension as he blazed his way to victory at Churchill Downs, sprinting each quarter-mile faster than the previous one. Then he won the Preakness. As a result, the press coverage was smothering leading up to the Belmont. "That week was hell week," Chenery says. "Everybody wanted an interview. I couldn't go to the market without (first) having my hair done. People would recognize me and ask for an autograph at the A&P. There was just no peace."

Her horse didn't disappoint. The image of Secretariat's dominant 31-length victory to win the first Triple Crown in a quarter-century, along with Chenery in a box seat flailing her arms and smiling that famous smile, is burned into fans' minds to this day. It's something Chenery couldn't fathom until after the race, at an Italian restaurant Lucien had picked for the post-Belmont meal.

"It was over dinner that we really started talking about the race itself," she says. "I thought, ‘My God! Thirty-one lengths!’ I'd never seen anything like it."

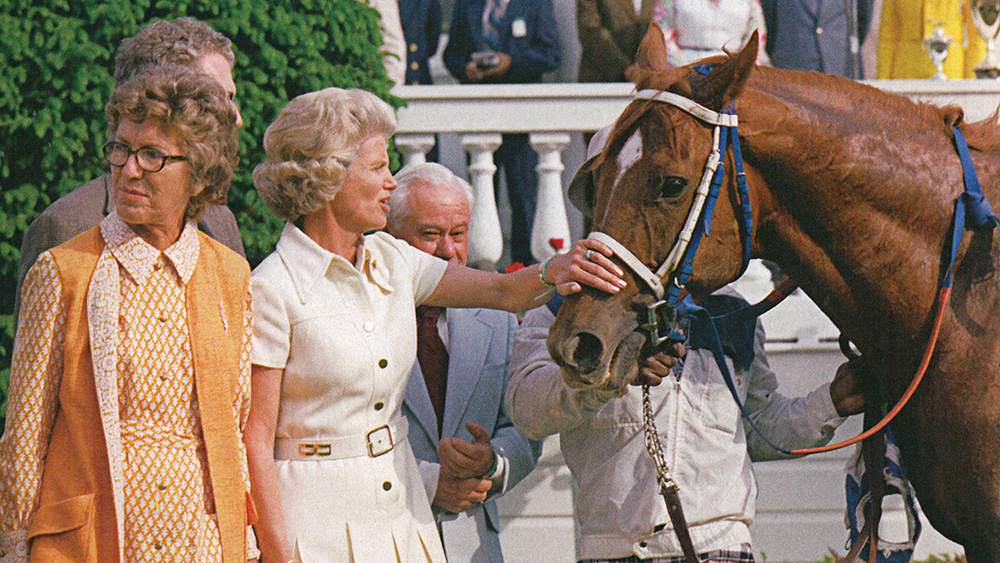

Chenery strokes the nose of Secretariat after his record-setting 1973 Derby win. // Horsephotos.com

*

As a repairman tinkers with Chenery's fax machine in her television room at The Academy, he glances at the apartment's walls. A single frame above the bedroom's doorway contains Secretariat's Sports Illustrated, Time and Newsweek covers. Pictures of Riva Ridge after winning the Futurity Stakes (the first major Meadow Stable stakes win under Chenery) and Secretariat after winning the Man O' War Stakes (his last race in the United States) hang on the wall too. Not to mention that the "first lady of racing" is sitting at her desk behind the man as he works.

"So, you're into horses?" the man eventually asks.

"Yes. My family was very involved with them, " Chenery replies. "And we had quite a bit of success."

"Oh, really?"

"Have you heard of Secretariat?" she asks.

"Yes."

"That was our horse," she says modestly.

"Oh, " he says, uninterested, as he answers his cell phone and scratches some notes into his binder.

*

Chenery wishes it were easier to find people who can talk horses. While The Academy's other residents — retired chemists, geologists, physicists and others — all have interesting histories, "They just don't know anything about horse racing," she says. To satisfy her passion she converses with friends on the telephone or reads The Blood-Horse and Thoroughbred Times. She keeps up with breeding trends and best-selling yearlings. "It's really pointless for me to continue my involvement, but, you know, I've got a mind full of it and the energy to be interested in something," she says. "I've tried to quit. I can't. It's what I do."

Chenery returned to Boulder and took up residence at The Academy in August 2005. Shortly before that, she'd been living in Lexington for more than a decade, but suffered a heart attack and two transient ischemic attacks (mini-strokes). Eventually, it became impractical and expensive for her children and six grandchildren to constantly fly from Colorado to see her. So Chenery settled in closer to them. "I hated it at first; I was seriously depressed," she says.

She completed cardio-rehab sessions, talked to a therapist (whom she still sees about twice a month) and started exercising regularly. "Getting old sucks," she admits. "But it's been great fun to find that I can regain my health and regain my energy." Now she participates in women's circles and current-events discussion groups and chats with her neighbors. And, of course, she still loves voicing her opinion about the sport she and Secretariat once controlled.

"Horse racing needs a good horse. They need a colorful, attractive owner, trainer, jockey — anything connected with the horse," Chenery says. "The horse is the hook, and then (fans) have to get interested in somebody in the racing world to identify with it. Otherwise it's a gambling game, and that's why we're losing. Gambling is impersonal."

Chenery speaks out because she still truly cares. It's why she currently owns two horses — a three-year-old colt named Spanish Galleon and a four-year-old filly named Cotton Anne. It's why she has www.secretariat.com, which sells merchandise and provides information on the super-horse. It's why she signs Secretariat Beanie Baby tags with a blue Sharpie pen until her hand cramps, hoping that she can somehow make a difference. "She's been the best ambassador for this sport that you could possibly imagine," Reed says.

Some may consider it a life less glamorous than the one she once led. Although she possesses a Churchill Downs box, she hasn't gone to the Derby in a decade. The day is too long. The crowds are too large. Her trips to the racetrack are now via a television set and a navy-blue-upholstered recliner. It is in this chair that she'll sit to watch Derby 133 on May 5. Alone. No flashbulbs. No questions.

"I'm really very intent on the race. People cheering — 'Come on big boy!' or 'He's making a move!' — that's just distracting," she says.

So she'll watch alone, or perhaps with a couple of friends — "if they promise that they won't say anything." As the gates crash open, her eyes will sweep over the whole field, trying to locate the winning horse as he makes his move. Then she'll peruse the reruns to see what happened to the favorite, see how the winning jockey controlled his horse.

After that, though, others are free to ask about her memories. About how she wept after Hill Prince didn't win the 1950 Derby and her father said, "Don't embarrass the horse." About how that same father, who was lying unresponsive in a hospital bed seemingly unaware of what his daughter was doing, cried when a nurse told him Riva Ridge had just won the Derby. About how, during his championship season, Secretariat perked his ears when the camera bulbs popped.

Chenery will smile her famous smile and talk for hours about the life she once lived. The life she's still living.

This story originally appeared in the April 2007 issue of Louisville Magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Cover art by Suki Anderson