A referendum on the ballot this November in

First off, don’t worry — the library of the future will have books in it. Despite breathless predictions of a coming Brave New World of paper-free, book-free libraries in which all the world’s knowledge will be contained on one computer chip, there will still be books on the shelves of the library for at least the next several decades.

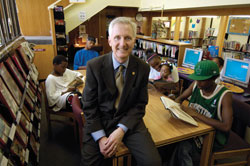

“We see the life of books in libraries extending at least a hundred years and beyond,” promises Louisville Free Public Library director Craig Buthod. “One of the things about think-tankers and futurists — and we do need to hear the things they are saying — but the place I disagree with them most is when they write off the printed book. I think that’s just too easy and too glib to say, and they’ve been saying it for 20 years. And I don’t see any indication of it.”

Which is not to say that the digitized, etherized, wizardized flow of information isn’t already a fact of life in modern libraries — the LFPL has placed hundreds of computers in its libraries, and they’re busy most every minute the libraries are open. Plus, everyone realizes that computerized information delivery is only going to expand in the future — even if they aren’t exactly sure how.

Library director Craig Buthod touts the system’s increased circulation and upsurge in card-carrying users.

Library director Craig Buthod touts the system’s increased circulation and upsurge in card-carrying users.

The

But keeping up with the explosion of technological possibility is just a part of the LFPL’s plan for the future. The primary thrust of the plan is new buildings. Buthod says the library felt that if it were going to ask the city to approve a referendum to create a modern library district, it had to present voters with a very complete plan for just exactly what it planned to do with its new authority and new funding. “We couldn’t just ask voters to trust us,” says Buthod. “We had to give them a plan.”

A big part of that plan, conceived back in 2004, is the construction and staffing of three new “regional” libraries — in Valley Station, Okolona and Lyndon — placed where large amounts of people can use them conveniently. “We need to make sure we have great libraries in the suburbs,” says Buthod. “That’s where a lot of people live now, and that’s where new libraries should be.”

The plan also involves building new “branch” libraries in Newburg and Pleasure Ridge Park, expanding or replacing 13 existing branches that are already strained past capacity, and upgrading the main library’s space, services and materials. “What we find today is that people want a range of services,” Buthod says, “and you can’t really offer a full range of services in a little dinky space.”

After consulting the

With the exception of a library built for the library system by the City of

The question arises, of course — is this grand expansion actually warranted by usage? The answer certainly seems to be yes. Business at the library is booming.

“Demand is through the roof,” says Buthod.

One doesn’t have to take the director’s word for it. A quick peek inside, say, the Bon Air branch, or Eline St. Matthews, or the Shively branch reveals the current high level of usage. The libraries are buzzing — with programs in place to further increase patronage and book circulation.

In each of Buthod’s nine years at the helm, the LFPL has increased its numbers of users and numbers of books in circulation. Currently, the library boasts nearly 500,000 card-carrying members. In 2006, the system registered 3.8 million visits, with more than four million books checked out. Inside those numbers, 1.4 million children’s books were borrowed and 202,000 children attended library programs, with 28,000 completing summer reading programs. Meanwhile, 951 people took their GED exams through the library, and 43,000 people attended 2,929 meetings at

Amenities for library users are part of the plan for the future, including more comfortable furniture and maybe even some sort of coffee service. “We want to find out what attracts people to the library and reward them with what they want, to bring them back,” says Buthod. “For example, one thing libraries have found is the students of today want to work in groups. They want to push chairs and tables around to get the setting the way they want it. So there are some living-room aspects to it.”

“It’s as much about how you build new buildings as what you put in them,” says Garvey. “When you look at how much libraries have changed in the past 10 years, and continue to change, the best thing we can do is build a flexible space that will work for us in the future. So that we are making a sound investment when we build these buildings.”

With its new flexible spaces,

“We’re about education; we’re about lifelong learning,” Garvey says. “The public library has always been, and I believe will continue to be, the people’s university. It’s where anyone can go to learn something.”

In

“We strive to be very community-centered,” says Telli. “Our neighborhood is particularly urban, with people grappling with the ‘digital divide.’ They need help with the requirements of immigration, learning about citizenship, applying for jobs. Today, people have to apply for jobs on computers, and while many of us take that skill for granted, computers are not ubiquitous in everyone’s homes. Those are people we work with everyday.

“And,” Telli adds, “we’re always trying to bring in new people we would not normally attract, with author visits and workshops. We have very strong programs in which we partner with

Which is not just a

“We hired someone at Iroquois for ‘outside sales,’” as Buthod puts it, “somebody to get out into the community telling what the library can do. It’s a really clear example of people who come to this country with no history of what the public library is all about, so we had to tell them and show them. And at the same time we had to be responsive to people who had been in the neighborhood a long time.”

At the

“

FYI: You know those “A Library Champion Lives Here” signs that have sprouted up in yards around town, like the ones political candidates plant before elections? Well, it turns out they don’t go to folks who have pledged $50 at a fancy fund-raiser, or something like that. The signs are individual trophies students earn by completing the summer reading program. It’s not their parents’ sign. It’s their sign.

Young library readers are rewarded with a sign of accomplishment.

Young library readers are rewarded with a sign of accomplishment.

“For a long time librarians assumed their job was to open the doors and be responsive to the people who came in the doors,” Buthod says. “But that’s not enough. We have to show the library’s value in the community and help people realize the library can help people in their lives.”

One city’s library system has proven to be an exemplary model for Buthod. “

“The mayor was saying the libraries and firehouses are emblematic of a permanence of the neighborhoods — that we’re here for the long run,” says Buthod. “He was saying that in this community we are about education. And he delivered the goods.”

The

Buthod says he’d like to make the library “a 24-hour shop, so you can deliver content around the clock,” and also have librarians available online for chat-session support.

One special dream of the LFPL is to offer its extensive Kentucky Room collections online. The room is a veritable treasure house of rare books, paintings, letters, manuscripts, recollections and other exclusive sources of information about

“Where we would be really interested in the technology of the future is in digitizing our Kentucky Room, getting into electronic format information that is uniquely held by our library,” says Buthod. “It’s stuff we could make available for the whole world to see. We especially want to make our files from the Kentucky Room available here in every school and at home by computer.”

The LFPL website continually adds new services, an example being practice SAT and ACT tests students can take online. The program scores the student’s test effort, then offers evaluations of which areas test-takers scored strongly in and which they did not. Another nifty example: An on-the-road library member with a Windows-compatible laptop can download books on tape and play them through the car’s radio. For the library there are no disks or tapes to break — and nothing’s ever late.

“If the basic operation of the library staff a few decades ago was to check in books and check them out,” says Buthod, “we want to automate that so the staff will be able to help kids with their homework and teach them to understand the importance of reading, as well as to answer the research questions of adults.”