Introduction by Anne Marshall

Interviews by Arielle Christian

Photos by Jessica Ebelhar

Public-school teachers have endured a bruising year across the country, and that includes Kentucky and Jefferson County Public Schools. When they protested Gov. Matt Bevin signing a controversial pension-reform bill, he cursed Kentucky public school teachers on the regular, accusing them of being “selfish” and “ignorant,” even labeling their efforts as a “thug mentality.”

When on the defense, it’s helpful to lock arms, find support. For teachers, that’s the positive takeaway from 2018. “Teachers have found the voices and we’ve found each other,” says Kelsey Hayes Coots, a language-arts teacher at Marion C. Moore School, a middle and high school on Outer Loop. In March, she helped organize teachers in Jefferson and surrounding counties to protest a last-minute pension overhaul by legislators. The night that happened, she received 750 Facebook friend requests from frightened educators seeking guidance and comfort. The hashtag #120strong was born, the 120 referring to the number of counties in the state. In reaction to a possible state takeover, “Our JCPS” signs popped up in front yards.

“If our students name-called like (Bevin) they’d be in lunch detention,” Coots says. “It’s disheartening.” (Lest we forget, it was politicians who mismanaged the public retirement system, leaving it as one of the most poorly funded in the country.) Then, of course, came that late-Thursday-night passage of a 291-page pension-reform bill, sneakily stuffed into a bill dealing with sewer-system regulations. Angry chants from teachers — “Do the right thing! Vote them out!” — echoed for hours in the state capitol.

When teachers statewide called in sick, striking, Bevin suggested they were leaving children open to harm, even sexual abuse. Coots watched that news clip four or five times in the parking lot of a grocery store, stunned. Tears well in her eyes when she talks about it. “That’s a despicable thing to say,” she says.

Scrutiny, that’s nothing new for teachers. Parents, politicians — we all weigh in on education. Maybe it’s because most of us spend 13 years — kindergarten through 12th grade — in the classroom. School feels nearly as familiar as home. The teacher: an often loved/sometimes despised/hopefully cheerful/occasionally wicked/at best, inspirational dispenser of education. The school years are formative, carried with us forever. We’ve all been there. We know it. So there it goes, Bevin breezily labeling JCPS an “unmitigated disaster,” and, this year, deciding to shuffle the state school board and hire an education commissioner eager to push for charter schools and a state takeover of the district, something that was ultimately avoided.

“We’ve always had a sense that we’re not treated like professionals, like we’re semi-professionals,” Stephanie Cutler says. Cutler is a kindergarten teacher at Slaughter Elementary in Newburg, a school in which most children qualify for free and reduced-price lunch and half are not native English speakers. Nearly every week, she prepares 76 different lessons. There are the classroom core lessons, small group lessons, lessons for English language learners, lessons for students who are behind and pulled for extra intervention, lessons for her advanced kids. She has embraced new initiatives on the district level involving equity and project-based learning that encourages students to think and solve problems on a deeper level. Some teachers resist the change, bristling at the lingo and souring at the stress of it all. Not Cutler. “We have to teach them to be independent citizens,” she says.

That’s the goal. But, for now, they’re still kids. Cutler packs snacks into backpacks for students who might not have enough food at home. She does laundry at school when parents don’t have the means to wash clothes. She’s a shoulder to lean on, a steady adult who absorbs hurts and worries and fears. “I don’t know any other profession where people stay up late at night worrying about someone else’s child,” Cutler says. “I’m not their mom, but some call me their ‘school mom.’”

She’s not alone. Over the following pages, you’ll meet teachers who live, breathe and wholly commit to their profession, just seven of the more than roughly 6,700 JCPS teachers, in a district with more than 98,000 students. Nominated by their principals, they have felt the stress and heard the noise that 2018 delivered, but every day these teachers show up with eager purpose, undaunted by the task of educating students with diverse, sometimes challenging, backgrounds. Never mind what the world thinks. They’re here, charged with helping students mature, in mind and so much more.

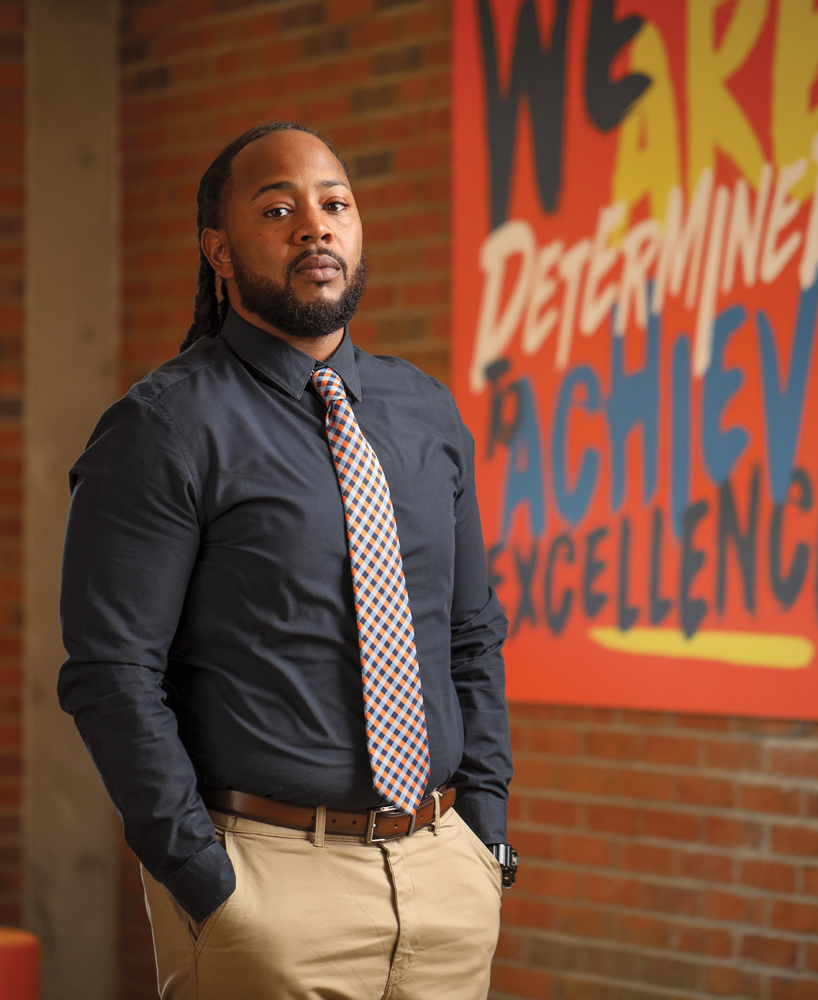

TROY DUNCAN

Eight years teaching

W.E.B. DuBois Academy, sixth grade

What are some things you’ve learned teaching at DuBois, which opened this school year and mostly consists of African-American males?

“My background has been with high school students. My approach has had to change. I’m an upfront, honest teacher. Sixth-graders can’t handle that as well as 16- and 17-year-olds. I’ve had to tone it down to reach younger children. They’re a harder group to reach, because they’re right in the middle of that transition between a small child and pre-teen. The best thing I’ve done is to genuinely listen to my students and allow them to take more control of the class, more of the flow.”

You’re very involved with the kids — conducting home visits, staying after school with them.

“I am extremely involved. And a lot of the teachers here are. I’m ECE (“exceptional child education,” for students with learning disabilities) and my background is with special-needs students — I taught at schools where students were lower functioning. So, literally, as a teacher, I’ve cut hair, I’ve clipped toenails, I’ve given rides — I’ve done everything. Not just me, but at the DuBois Academy, the line between teacher and parent is blurred. We’ve been called to a position where we do a lot of parenting to children who aren’t ours so that they can be successful. Sometimes you have to have staff that can pick up the student to go to a basketball game. Or go to an event on Saturday to help students. It’s above and beyond the call of duty, but for these young men to be brave, they need to see us doing it.

“It’s teaching these young men how to be young men. How to carry themselves. How to respect themselves and respect others. How to live. How to function through this world as minority men. Because our experience in this society is different. I pride myself on teaching them things that aren’t publicly spoken on that they need to know. For example, it’s something as small as — I don’t like seeing these young men walking around with hoods on their head. Yes, they have all the right in the world to do it, but if you know that makes people uncomfortable or suspicious of you, make the wise decision and don’t walk into the store with a hood on your head. It isn’t right that people in our society are so uncomfortable with you dressed like that, but I want you to be wise enough to know that, so you can make a wise decision. Because what matters more at the end of the day: walking around with a hood on or making it home safe? It may not be in a book, but it’s things they need to know to survive in society.”

Can you talk about the DuBois Academy’s mission of “culturally responsive teaching”?

“I’m an African-American man. I know I may be pre-judged because I’ve got long braids, dreads, whatever you want to call it. But I pride myself on being a well-rounded man. I tell my students all the time: I can go in any setting in this city, and I know how to blend in. I can go to the art museum and fit in fine or I can go to Shawnee Park and fit in fine. My ultimate goal is to make opportunities for these young men. Whether that be going to college or being a plumber.”

In high school you were in a Men of Quality group at Male High School. Do you see similarities between that and DuBois?

“In a nutshell, Men of Quality is a small version of what we’re doing at this school. Men of Quality takes young African-American men and pairs them with an African-American mentor to expose them to new things. It taught me how to dress myself. How to code-switch, which is a huge thing — or, as I tell my gentlemen: knowing when to turn it on and turn it off. Men of Quality taught me that how I present myself at a football game with my buddies is different than how I present myself at a job interview or when I’m sitting down with my principal and discussing my grades. Knowing how to switch my language, switch my looks. That was the main thing: learning how to adapt to the environment that I’m in.”

That had a big influence on you. Is there a specific teacher who really influenced you?

“Hands down, Kevin Nix. He was my fourth- and fifth-grade teacher. I believe he retired from JCPS four or five years ago. (He briefly served as an interim principal earlier this year.) He was my first male teacher. Until that point, I was a pretty rough kid. I had been referred to be in an ECE room, self-contained. I was an angry kid. Even till this day, I don’t really know why I was angry. But in fourth grade, I was placed in Mr. Nix’s class. I guess maybe it was the authority or his deliverance — he had a certain way of reaching young men. That’s when I started getting it together in school. I haven’t seen him since I was a child, but I still credit where I am now to him. He was the cool teacher, the understanding teacher. The teacher that, even though we were from the city and rough around the edges, he still treated us the same.”

Are there classes where you’re teaching African-American culture?

“No specific classes, but I find ways to incorporate that into it. Great example: For the last two weeks, I’ve been teaching unit rates, or calculating the rate of sales for anything — miles per gallon, how much apples cost per pound. A unit rate that I taught was BPM, beats per minute. How they measure the tempo of a song. Well, a way for me to embed African-American culture into that is through rap music. They love beat-making. They’re beating on the tables constantly, rapping any chance they get. So, I made a math lesson incorporating beats.”

Did you play them music and have them analyze it?

“Oh, yeah. There’s music going constantly. My students work to rap instrumentals. That’s been one of my tools for being effective as a teacher. I’m only 31 years old; I’m relatable. That’s probably the biggest advantage I have. I look like these gentlemen. I dress like them. I like Air Jordans like they do. I listen to Lil Wayne like they do. I make it a point as a teacher to stay relevant. I hate using this word, but: hip. When you can’t relate to the students, it’s harder to teach them. Or you find yourself getting on them for something they enjoy.

“I meet the students where they’re at. If you need rap music to learn math, I’m going to bring in my whole hard drive. Clean music, of course. Or — a lot of my students live in poverty. They face situations where they go to the grocery store and mom only has 50 dollars for the week. How is she going to budget it? I wouldn’t say, ‘Well, Johnny’s going to the store and wants to buy some apples.’ They can’t relate to Johnny. They relate to mom going to the store and making the money stretch. That’ll stick with them.

“You know what Fortnite is? There’s a silly little dance in the video game that the boys love to do. In any other school setting, if one of the boys broke out in that dance, they might be reprimanded. In my math class, if a kid gets a question right and they want to do the Fortnite dance, I’m not going to stop ’em. They’re not hurting anything. You’re having fun, you’re learning. Matter of fact, if you give me four great days of learning, we may play Fortnite on Friday.

“These things that I’m teaching them are the things that were taught to me by my father. That’s what made the difference between me being here doing this interview and me doing federal time like some of my buddies. When I was growing up, being in rough situations, I had my father’s and Mr. Nix’s voices in the back of my head.”

Tell me about “brotherhood,” which is a word I’ve heard used to describe the school.

“We actually pride ourselves on that. We post live videos every day. Every morning we have a five-minute session called Pass the Love. Our principal, Mr. Gunn, will usually stand up on the table and he’ll play ‘Lean on Me.’ For that three to five minutes, every gentleman has to stand up and go to another gentleman and pass the love. They hug, tell each other, ‘Love you, I appreciate you.’ It’s not an option to sit down. Even if you’re having a bad day. There’s going to be three or four other young men that are going to love you through that rough moment. We intentionally do things to break that mold of men having to be cold and thorny and not show love. As a man, I can’t stand that. It doesn’t make you any less of a man to show love.”

ASHLEIGH GLICKLEY

14 years teaching

Hawthorne Elementary, fifth grade

What got you into teaching?

“You know when you’d have those career days in elementary school and they’d tell you to dress up as the career you’d like to be? I can very clearly remember dressing up as a teacher when I was in, like, fourth grade. Hair in a bun, glasses, a little sweater on — not far from what I’m wearing right now! My mom’s a teacher. We have a lot of educators in my family. It’s just been something I kind of knew from the start. The more classes I took in college, the more it affirmed that this is what I really wanted to do.”

You’re teaching classes in Spanish?

“Here at Hawthorne, we do Spanish immersion, kindergarten through fifth grade. (Glickley taught in Guatemala and established the first Spanish-immersion school in Florida.) Our students spend half the day with a math and science teacher who only speaks Spanish in that classroom. It’s a bilingual education model where the students are immersed in the language. The content expectations are the same — the same standards as in regular math and science; they just do it in Spanish. The other half of the day, they do language arts and social studies in English. We focus specifically on math in Spanish because it’s such a visual subject area. Like writing the numbers — we’ll teach them how to spell the numbers in Spanish — but when I’m teaching and putting numbers on the board and speaking in Spanish, it’s still clear what we’re working on. But we have a literacy component within the class. Our goal is for students to be bilingual and bi-literate by fifth grade.”

Is the population at Hawthorne mixed or mostly Spanish speakers?

“We currently have a lot of native Spanish speakers in the classroom. It’s really special for them, because they become the experts in the classroom for the language. It’s nice, because the other students are all looking to them to help classmates express themselves better. In my fifth-grade class, we play games, set a timer, see how long we can go to speaking Spanish. Really challenge the students now that they have had five or six years of Spanish to speak to each other. Which can be the biggest obstacle, because you look at your friend and they speak English. You have to challenge them to speak in another language together.”

What’s a tool or trick you like to use in the classroom?

“We’ve been having a lot of conversation about keeping kids engaged at our school. Doing more project-based learning. Having more choices in the classroom. Last year, I went to the principal and was like, ‘I really need Chromebooks. We need more technology in the classroom, so that students can develop these projects to prepare them for the future.’ Just to give them that knowledge and experience. Now we have a class set of Chromebooks. They’re working on projects with a lot of choice and individual decisions about how they’ll learn the material they’re learning. That’s been amazing, because last year, some students were really turned off; I was really fighting to get them engaged. They’re excited now. It was neat to see how meeting the interest of that child changes them completely.

“The other thing we always work on here is developing relationships with our students. The biggest thing is letting them know I care about them and want to get to know them. You can’t ask someone to do something if they don’t have that confidence and trust in you. That was a transition in my career to be able to say, ‘OK, this is classroom management — to create these relationships with my students.’”

What’s a project you’re currently working on?

“We are writing a story. We found this really cool story about this little girl who opens the door into her imagination. We’re using that for inspiration during our Spanish literacy — they’re writing a story about what it’s like to go into their imaginations, and if they were to let somebody into their imaginations, what would that person see? One of my students is using a spiral staircase to lead to her imagination. I’ve honestly had to tell them, ‘OK, please put this away. We’ve got to work on something else now.’”

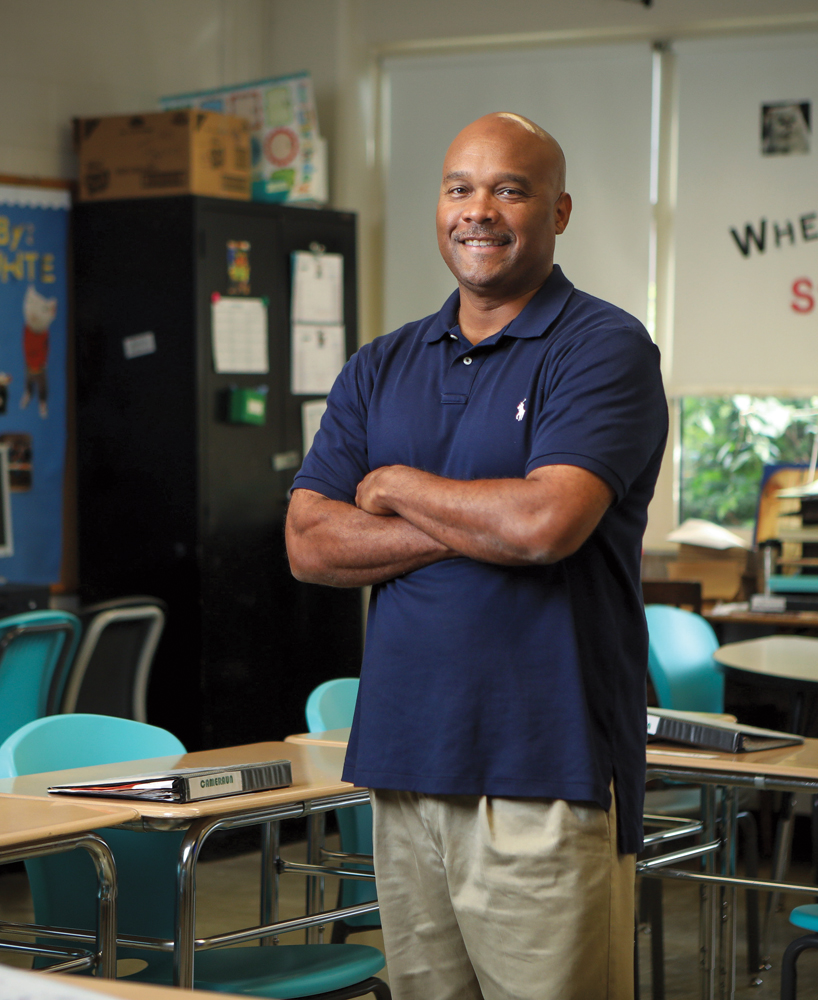

CHARLES MUCKER

Six years teaching

Binet School (for kids with a range of learning disabilities)

Why did you become a teacher?

“I’m a retiree from the Louisville Division of Fire, Louisville Metro Government. I was an assistant chief there. My mom was a retired teacher. I’d always coached football. I’ve always loved working with kids. I went back and got my teaching credentials at Spalding in 2013. As far as Binet, it’s a special place. You have to love the kids where they are — with the gifts they have or don’t have. We have about 100 students. About 80 percent are on the autism spectrum. It’s kindergarten to 12th grade at this school. The students age out at 21 as opposed to graduating at 18.”

What are you teaching?

“I teach reading to 10th grade. Math. Social studies — that’s probably my strongest subject. I teach world history, a cultures class. But I do a lot of job training with the students as well. We take our students out in the community and train them on doing jobs. How to be socially appropriate in public. How to actually do the jobs. We have students who work at the zoo or UPS. Where some of our students may have met their academic potential, we train them for life after Binet. We have a jobs program that’s part of our focus. We go out three days a week in the community working with their skill set. This week we’ll go to the C.B. Young and Dawson (school-services centers). We’re responsible to fill the Coke machines there. The students will take inventory of the product there. They’ll collect the money out of the machines, count it, turn it in to our bookkeeper. They fill the vending machines. They’ll transfer inventory from one location to the other. I have two students on Monday and Thursday who are in that training program. We also have students on Wednesday that go to Dare to Care and put together food packages for disaster relief or to feed locals. That’s teaching them how to be a productive citizen. How to have an independent job.

“When I was hired, I was assigned a very difficult student. When I first started working with him, he was only able to function in the classroom environment for five minutes. I worked with this student for three years, and by the time I was done working with him, he was doing a full day of school. We went from five minutes to a full day of school. We took this student out on job sites. I shared some of these strategies that I used with him, to pass this on to other teachers to use with other trying students.”

What’s the best way to handle difficult students?

“I’ve had students with severe hygiene issues. They’ve been self-mutilating. Being able to deal with students that would pee on the floor and try to kick it on me. I was an EMT at the fire department, so I was used to dangerous or hazardous environments. Having a student in crisis, or seeing blood — I had over 20 years experience dealing with emergency incidents. It didn’t really shake or rattle me.

“When the fire’s going through the roof, you have to be able to function. With a student in crisis, you have to be calm. The way you handle the situation can either escalate it or calm it down. I’ve got to be able to take a step back, give it time, not antagonize it. I’ll be the voice of calm while everything is going 100 miles per hour around me.”

What makes a good teacher?

“I think the key to teaching — whether school or football — is genuinely caring about your kids. If your kids know you care about them, they’ll run through a wall for you; they’ll really try to learn the material.”

What do you make of so many teachers on this year’s electoral ballot?

“Statewide, the pensions teachers are working for, that’s an incentive to teach. That being under attack is pushing people to the forefront. One of my friends is running, Ronel Brown (a retired firefighter and now an instructional assistant with JCPS, who lost in the November election subsequent to this interview). Part of his platform is involved with saving education. I think that’s why you’re seeing more teachers, first-responders, engaging in the political process. Some of the teachers in the building went to the protests. I didn’t, but everyone is shaken by it. When you give all that teachers give to the profession, and for someone to say you don’t deserve a pension, you don’t deserve to be cared for, it’s hurtful to educators.”

JAMA VOGT

17 years teaching

Atherton High School, ninth grade

Why did you become a teacher?

“It’s interesting, because I remember, even as a little girl, setting up my stuffed animals and teaching them the things I’d learn at school. Even as a kid, sometimes in class there were times other kids wouldn’t be catching on, and I felt like I could help them. The teacher would always ask me to help other kids. I’ve always had that interest in me. I love to read and write, so the idea that I could work with students and help them become better readers and writers was appealing to me.”

What were some of the best tools you picked up as the resource teacher? (Vogt teaches freshman English and leads Atherton’s newly created freshman International Baccalaureate (IB) Academy. She has held several positions in JCPS, including as a district resource teacher.)

“You know, when you step back and look at a classroom through a different lens, when you’re not the official teacher anymore, you just notice things. I’d notice teachers who made sure that every single student’s voice was heard, even students who didn’t feel confident and didn’t want to share. It’s so easy to call on the hand-raisers. Watching people make their students feel confident and understand challenging content, being able to step back and have time to have the conversation about lesson design — it made me make sure that my own lessons are challenging, that I’m providing good interventions for students who aren’t getting it. Am I differentiating so that the students who get it are being challenged, and those that don’t, can? It’s funny: I don’t teach a file cabinet of lessons. I don’t use my lessons from year to year. I don’t want to become that teacher who’s using the same yellowed copies. Every year to me feels like a new year. I may teach the same text, but I’ll always try to approach it a little differently.”

Can you talk about being an International Baccalaureate school?

“The bar is set very high for them. The kids want to feel like that bar is high. From the moment I stepped foot in Atherton, it was very obvious to me that the kids in the building — even the ones who weren’t in IB or AP classes — were proud to attend this school. One of the things we wanted to do is make sure our incoming freshmen understood what it meant to be IB. When we look at the IB learner profile, the students are balanced, good communicators, knowledgeable, open-minded, reflective, risk-takers, thinkers. We’re really trying in the freshman academy to see how they fit into those categories. What did you do today that made you a risk-taker? Why is it important that you did that? When the kids here see that you’re not just looking at them as a student, but as a risk-taker going out into the world, a positive global citizen who’s making change, it changes the atmosphere. The kids feel a sense of belonging and purpose.”

Have you seen major changes in kids through the years?

“These kids are growing up in a world — they were born after September 11th, mostly. I don’t even know how I’d deal with that world. Because I’m older — I mean, I didn’t even have a cell phone in school. If we don’t teach these kids how to be a positive influence, we’re really doing them an injustice.

“It’s forcing me to grow. I’m having to get with it in the 21st century. I’m having to learn new technology, and it’s not easy for me. Kids have access to the world. Internet, phone, social media. I have to be able to keep up with that pace. It can be a beast sometimes. Especially when you’re teaching kids who don’t find reading the most appealing. It’s hard to get kids to slow down.

“But I’m trying to teach kids to slow down and read more closely. We’ve been in such a habit of trying to read a lot very quickly. Kids get rushed even on timed tests. I’m trying to get kids to look at the reading in smaller chunks, to interact with the reading. For example, right now my students just finished learning about allusions. Rather than teaching about allusions and looking for them in the text, I want them to think about why an author would use allusion. What would be the purpose of using this? What if the author hadn’t done this? How would that change the text? I teach them to stop and interact with the text, so they can really focus on it.

“I had a young lady at the beginning of the year who admittedly said that she just wanted to sleep; she didn’t want to read. I started talking to her about some of her interests — TV shows, movies. I pulled her a stack of books. I’d have her read a paragraph of some of the most exciting parts in the books, so that she could see where it was going. I think she told me the other day she was at five books, which, for November — that’s amazing. This was someone who was adamant about hating reading. I’m really proud to help a student feel more comfortable. I’ve set a goal for every kid to work toward reading 25 books by the end of the school year. She may not read 25 books this year. She may — who knows! I can’t wait to find out.”

KAMALA COMBS

30 years teaching

Maupin Elementary, fourth grade

Why did you become a teacher?

“When I was a little girl growing up, I always had the knack for sitting down and playing with kids. I was one of the youngest in my family. I could never fit in with the older kids — you know how that goes — so I would end up with all the little guys. As I got older, I taught Sunday school. I went to camp. I always felt that it might’ve been my calling in my life.”

You’ve been teaching for 30 years. How do you persevere?

“Over my career, I think I’ve been in 19 different schools. I’ve taught in four counties in Kentucky, and I taught in Florida for 11 years. Just meeting different people, learning different cultures — that’s part of it. I didn’t get caught in that rut and stay there. That’s helped me the most. Have there been times in the past when I thought, ‘You know what? I don’t know if I can continue doing this.’ There have been. Working with kids can be stressful, but never to the point where I’m going to walk out.

“I started my teaching career in sixth grade at a school in Eastern Kentucky. It was way out. Way out. I drove 45 minutes to get there every day. I had 12 sixth grade students in a nurse’s office — and you know those rooms aren’t very big. We had tables crammed in there. I was there for a year. I taught special education for two years. I taught music and the arts to kindergarten through eight grade. I’ve taught just about every grade level except for kindergarten.”

What major changes have you seen in education over your career?

“Oh, gosh. I was thinking about this the other day. Education — it seems like a cycle. Things I saw 30 years ago when I started to teach — like using textbooks — went away for a while. Then they came back. Then using workshop models. They’re all things we’ve done in the past and it’s circled back through with a different name. It’s just one of those things. Education has been really, really tough. Working in Jefferson County, the pay is extremely good here, compared with any other school district I’ve ever taught in.

“There’ve been counties I’ve taught in where it’s all about the numbers, all about the testing. How far can you push your kids to go this year? In Florida, as I was leaving there, they were going to do performance-based testing. Your pay was going to be based on how well your kids did. That was crazy.”

What’s the most important thing in guiding the classroom?

“I’ve done a lot of reading about positive mental attitude, about how to get the best out of people. I could name book after book. When I came to my classroom at Maupin, I decided — let me just load this down on you, girl. I was setting my room up before school started, putting my scissors out, my glue out, containers. I had someone come to my room and say, ‘Hey, Mrs. Combs, you might not want to do that. The kids will take them and you won’t have any to work with.’ I automatically put lids on the containers or put them back in the cabinet. I kept getting the feeling that the kids couldn’t be trusted, that it was really a bad school. Even when I was leaving Shelby County, a lot of people were making comments. ‘Why would you want to go to a school like that?’

“You know, I work with a lot of Kentucky Refugee Ministries families, and that was one of the biggest reasons I decided to come back to elementary. I missed teaching kids to read and write. Trying to get my room set up and get everything going, I realized that the kids that I work with here, they need to feel a sense of belonging. They want to be a part of something. We all want to be a part of something. I wanted them to fit in my classroom, to feel wanted and loved in my classroom. And, of course, I’m white and all my kids are all black. Last year, I had one white girl. But they’re no different than I am, and they know that. They know Mrs. Combs thinks that. So in the morning when I have my morning message up, it always says things like, ‘You are the best.’ I want them to believe they are the best. Because they are. They work hard and I believe if we instill in them the value of who they are and who they want to be, I believe they’ll rise to the occasion.”

How do you help kids who come from a bad home and might live in trauma?

“It’s hard, I’m not going to lie to you. I could cry right now, because — oh, my gosh, don’t go there. There are nights that I don’t sleep, because I want so much for these kids. I want more for them than they can see. Right now, they can’t see what’s out there for them. Because of their life situations. And they’re young right now. They really don’t know what they’re missing. Sure, they watch TV. Sure, they can see out there, but they don’t really understand. A lot of these children don’t leave the city of Louisville. The only way they get out is if we take them on a field trip. Even going across the Ohio River, they’ll ask, ‘Is that an ocean?’ ‘No, baby, it’s a river.’ You know what I’m saying? That’s the kind of things that I hear. They don’t really understand what life can be for them.

“Girl, this is the toughest job. You don’t sleep at night, and you’re laying there thinking about, ‘How am I going to teach this lesson? How am I going to tie this in?’ Even being here, the expectations are the same as they are at Manual High School. I have to teach to standards, even though a lot of my kids are on the second-grade reading level. Do I back up and teach them what they miss? Or do I teach them fourth-grade stuff that they can’t even read? It’s a balancing act. But, to me, if they grow, as a student — yes, on tests, but more as a young person — that’s what is important to me.

“Every bit of the positive we can give these kids is needed. It’s needed in every school. You have people who look for the nitty-gritty little things that I think are petty. Who cares if you’re out of dress code — you’re here today. I’m not worried about it. I’m not real sure why they are (out of dress code), but it’s usually one of these things: one, they didn’t have anything clean, or two, they didn’t sleep at home last night. It’s not their fault. I read this book, I Wish My Teacher Knew, and I learned a lot. You’ve got to learn to say I’m sorry, especially to these kids with trust issues. There’s so much more to teaching than teaching. That’s why with our governor — I don’t understand his thinking. I don’t understand it. He has no idea how hard, on a daily basis, it is to come in and teach.

“I have one little boy who just had a baby sister who was born three months early. His mom is in the hospital with the baby. His dad works long shifts. He’s between his grandma and aunt and bouncing all over the place. Everything’s really confusing to him. To come in here and sit for six hours — that’s not going to work for him. We have to do a lot of getting up, moving around. These kids, their culture is very verbal. It’s loud. I had to get used to that. But they’ll learn that there are times for quiet. Like at a restaurant. I’ll eat with them in the cafeteria every day. I don’t have to do that. But I sit with them and we have a conversation to learn a little more about each other because we can’t do all of that in the classroom. You’re teaching many aspects to their lives.”

JENNIFER WADE-HESSE

12 years teaching

Olmsted Academy South (all-girls middle school), sixth grade, language arts; seventh grade, Young Authors Greenhouse creative-writing program

Why’d you become a middle-school teacher?

“It’s not what I started with. I got a master’s in education at U of L, in specifically college personnel. I worked at several universities. I ended up as an academic advisor for students on academic probation. Some of those kids would say that they hadn’t enjoyed school since middle school. I thought: What are we doing wrong? Why were we losing students in middle school?

“Since I got my job in 2007, I haven’t looked back. It’s amazing. Even on my worst day, I never think about quitting, or moving up in education, out of the classroom. I picked the right age. They have all the basics down and now we get to talk about real things, explore real issues and figure out who we are. That’s part of it for me. It feeds my soul.”

What is your classroom’s focus?

“I have this strong desire that the girls leave my room seeing themselves as people who have a voice and a contribution in the world. Women haven’t always had advantages that these young women not only have, but demand. I want them to know that they come from that history and culture, as well. We research influential women. Our independent reading is geared toward strong, female protagonists. It’s not a girly room. But we explore the idea all year long: What does it mean to be a girl in the 21st century? That’s kind of the undercurrent in my classroom.

“A couple years ago, we started the year with Malala Yousafzai, the young woman who was shot by the Taliban for continuing to not only go to school, but for advocating for girls’ education. You know, sometimes kids don’t want to be in school, but we can show them, no, look, it matters that you’re here. What you’re doing here has purpose beyond you. I get the students in sixth grade and they’ll go on, so I don’t always get to see the results of these seeds that I sow, but I’m pleased to sow them anyway.”

How ethnically diverse is your classroom?

“We’re 16 percent English-language learners. It’s a wonderful mix. We have a number of Somali students, Middle Eastern students, girls from Myanmar, South and Central America, Cubans. We’re almost entirely free or reduced-price lunch. But that doesn’t slow anyone down. They’re just as capable, engaged, interesting. We fly under the radar in the district, but anyone who walks into our building knows it’s something special.”

Any unique aspects to your teaching style?

“What I love about language arts is that I can teach the standards using anything that is of interest to the students. Anything that requires them to read, critically think, communicate those ideas. It’s awesome to just step back and stay out of the way. My real job is to set up the circumstances where the girls are engaged and they construct their own understanding of the world. I’ll give them a subject, or they’ll pick one, and I’ll give them resources and guide them, but they develop their learning.

“In the Young Authors Greenhouse program last year, we did a ‘What makes me angry?’ poetry activity. Incredibly powerful. It was shortly after the Parkland (Florida) shooting. Some of the girls wrote about school shootings. Some wrote about their relationships with their parents. I saw this kernel and thought about taking it further. What kind of argument can I craft to make this situation better? A big part of my class is sharing. Standing up and sharing what you’ve written. Sitting in a Socratic seminar and sharing your thoughts, responding to others. I said: You can present your argument however you want. You can write it as an essay. Create a website. And this girl was like, ‘Can we do this as a TED Talk?’”

What do you think about lockdown drills?

“For me, it’s all about keeping them calm. One year, I had an encyclopedia of mysteries, and the plan was, if we had a lockdown drill, I’d read it to keep them focused. I hate the thought that it happens. I do everything I can to keep them calm and keep them safe. We talk about our options. The district is unveiling Alice (active shooter response) training to allow folks more freedom of choice in how they respond. I’m trying to wrap my head around it. I have a three-year-old and she is at a preschool and they have these drills. She was explaining to me, ‘This is what we do when the strangers come.’ I was like, ‘Dear, God. What? What?’ This is the world we live in.”

Anything else?

“I remember being around the sixth-grade age, sitting on my mother’s bed. I was crying, I was angry. I don’t remember why. And she said, ‘I don’t understand, I don’t understand. Maybe I don’t remember what it’s like.’ I remember clearly thinking, ‘Not me, I’m going to remember. Don’t forget what this is like. You’re going to need to remember this.’ I can see these feelings in my students and I have empathy. It’s usually around March when I’ll have to have this conversation with the girls. We’ll have the conversation, ‘Have you noticed that you’re really mad at your parents?’ They’ll smack the table, ‘Yes, ma’am.’ I’ll say, ‘Have you noticed that you’re mad at all your teachers?’ And they’ll groan. ‘And your friends?’ Then I’ll say, ‘Guess what, guys? It’s not them. This is just part of the process. This is where you are. This is what seventh grade is. You’re frustrated, because you want to go fast and slow at the same time. It’s OK to be frustrated, but let’s go a little slower with our frustration.’ It usually buys me five or six weeks. A lot of my kids, I can see them where they are, and they cut me some slack.”

THERESA REILLY

30-plus years teaching

Noe Middle School, eighth grade

Why did you become a teacher?

“I felt like I could make a difference. I teach math — and I feel it gets a very negative light. If I could help people understand it, or look at it in a different light, that would be awesome. As I’ve continued, I’ve learned a lot about ‘growth mindset’ and ‘mathematical mindset.’ My focus the last few years is helping students understand that it’s OK to make mistakes in math. Mistakes just help you along the way; it’s not a time to give up. You’re actually growing your brain and understanding at a much deeper level.

“I feel like it changes a lot of my students’ attitudes. It helps some of them work harder. It helps some of them feel better about their struggle. I had a parent who said, ‘Oh, my daughter doesn’t think she’s good at math.’ I said, ‘Have you checked in with her lately?’ She said, ‘No, it must’ve been last year or so.’ I said, ‘Check in with her again. I see her working hard, being OK to make mistakes and ask questions.’ I hope I’m changing views over the long run that people are more interested in math. Especially underrepresented populations, so they can get higher-paying jobs and reach higher levels.”

Why have you chosen public-school teaching?

“It’s more challenging. I taught in Catholic schools for four years. But here there’s a whole lot more room for growth — for me as a person. Learning to deal with a variety of people and trying to meet their needs. I’m over 30 years teaching, and I’m never bored. I have lower-performing eighth-graders, advanced-placement algebra, and gifted and talented geometry students. I’m teaching a wide range of abilities.”

What’s the most difficult part of being a teacher?

“I think it’s challenging to help kids to learn math who are struggling with one of their parents being killed in a shooting over the summer. Or if they’re homeless and don’t know where their next meal is going to be. Our kids deal with issues that are far more important in their life than education. We try our best to (make them) feel comfortable and safe, but it’s challenging to meet that many needs at one time.

“I do the best I can to develop a relationship with them. I’ll check in with them if I know something’s going on, see what the status is. I have one kid who — I have peanut butter crackers in the room, and she’ll ask for them. She’ll usually ask for them at the end of the day, and I wonder if that’s what she’s taking home for her supper. Or if we think a kid needs a coat or something, we’ll send them to the Youth Service Center. You try to meet as many of those needs as you can. No matter what they dish out, every day they come in, they have a clean slate. They might have cussed you out the day before, but the next day they come in and you say, ‘OK, today we’re going to be successful.’”

How do you handle outbursts?

“Sometimes it’s standing close to them. Sometimes it’s asking them what’s going on. Asking, ‘Who or what has hurt you today?’ Sometimes they need a break, and I’ll let them go work in another person’s room, if they want. As far as trying to get the academics in, I’ll do extra math help once a week and invite them to come to that. Sometimes they will, sometimes they won’t. You do what you can. You know, not having a pencil is not a big deal. Not having paper is not a big deal. I make it clear that that’s in the room, if you need it, go get it. You make the little things inconsequential. There’s a solution to that that’s no big deal.”

In what ways have you seen education and students change in your 30 years teaching?

“The struggles that kids have today, I feel like there’s more now that they have to deal with that they didn’t 30 years ago. There were still kids who had a difficult home life, abuse, but I don’t think there was as much homelessness. Or if there was, I wasn’t as aware of it. Substance abuse wasn’t as prevalent then. There are some factors in society that make it really challenging for kids to grow up these days. We have to acknowledge that they’re doing the best they can, get them the help we can, then try to work on the academics.”

This originally appeared in the December 2018 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.