Photos by Mickie Winters

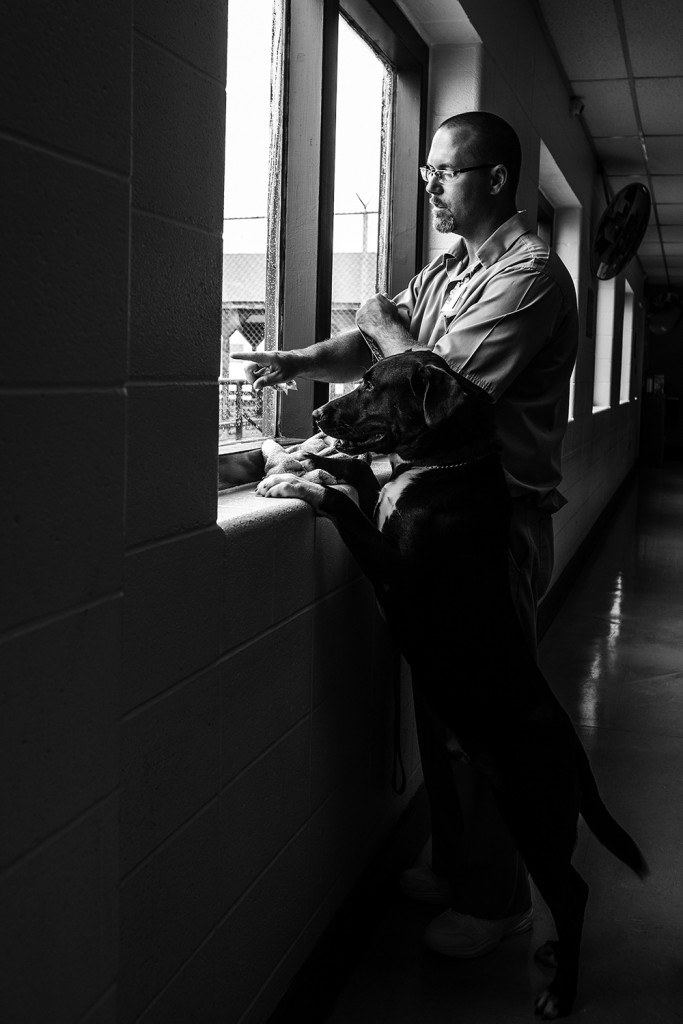

When Joey Johnson got Kenzi, a setter mix with dark, soulful eyes, she was skinny and dirty. “She looked like she’d been sleeping in a ditch,” he says. “Her fur was brown, ears were back. She was really scared.” Twelve days after Johnson and Kenzi met, I visit them at the Luther Luckett Correctional Complex, the state prison in La Grange where Johnson, 40, is serving the remaining four years of an 18-year sentence. Kenzi is groomed but seems down. “They took some puppies from her. She’s walking around whining a lot, looking for them,” Johnson says. “She’s in her shell still. I haven’t seen her personality yet.”

Johnson works for Paws Behind Bars, a state-run dog-training program for inmates facilitated by Adopt Me! Bluegrass Pet Rescue. Johnson and 11 other inmates — serving time at the minimum- and medium-security prison for things like robbery, murder, arson and drug trafficking — are each assigned one dog at a time to train and care for around the clock. Bluegrass Pet Rescue pulls about 300 dogs from shelters each year and 100 of those go through Paws Behind Bars, one of several such programs in the state. “We try really hard to screen the dogs that come in,” says Lisanne Mikan, who founded the rescue and helps run the seven-year-old program. She looks for healthy dogs that don’t show aggression but maybe lack confidence. “And they all come from shelters where euthanasia was gonna happen on Friday,” she says.

Joey Johnson with Kenzi

The inmates earn $2 a day to train the dogs, focusing on leash training, visitor control (not running up to people) and food control (not eating unless given the go-ahead). “Manners, composure, to sit here and not bother us while we talk,” says Johnson, who has trained 20 dogs over the course of his three years in the program. “See how she keeps getting up and I keep” — he pushes his hand on her back so she’ll sit by him. “I’m not focusing on her; it’s just repetition and being patient. I’ve made her sit probably a hundred times since we’ve been in this room.” Kenzi finally sits still for a moment. “That’s the composure.”

To be eligible for the program, inmates must have six months of clear conduct (no write-ups for getting in a fight or in any way breaking prison rules); have a high school diploma or GED; have a good institutional work history; have at least two years left on their sentence; and can’t have committed any kind of sex crime or have abused animals or children. The perks, other than living with a companion, include having a single cell. Angela Howard, the program coordinator at the prison, weeds out applicants, looking for cleanliness and social skills. Out of the current 980 inmates, she estimates that she has 50 applications.

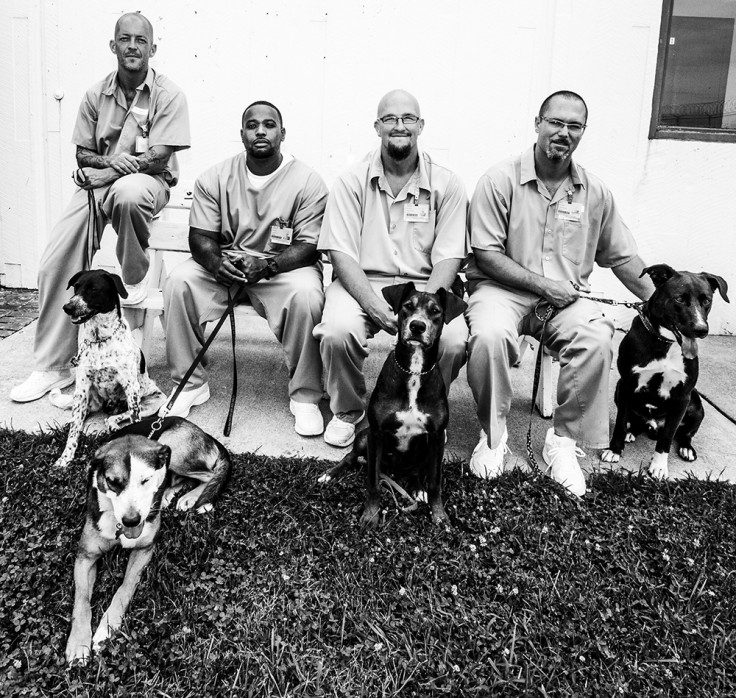

We’re in the visitor’s area, where I meet Johnson and three other inmates with their temporary dogs. There’s Apollo, who greets me with his chin on my leg, with Michael Johnson; Dunkin, a high-energy black Labrador/pit mix who came in five days ago, with Doug Hall; and Brixx with Carl Johnson. (No relation between the three Johnsons.) All four dogs behave better than my dog, who pulls on his leash, barks at houseguests and eats tissues out of the bathroom trash can. Motivated by treats and positive reinforcement, these dogs learn not to enter a room unless told to do so.

Doug Hall with Dunkin

“They can take their dog everywhere except the chow hall,” Mikan says. If a dog can handle the hundreds of inmates coming up to pet them all day, it’s ready for adoption. It usually takes six to eight weeks, but it can take as long as the dog needs. The adoptive families come to Luther Luckett for a meet-and-greet with the inmate and dog. Michael Johnson says that he tries really hard not to make any missteps, to make the dogs look as good as possible so that they don’t end up in the same rotating door of being unwanted. David Benson, who trains the inmates every few weeks to keep their skills sharp (they also attend seminars on grooming, first aid and stress management), is the executive director of Dogs Helping Heroes, which provides dogs to veterans, many of whom have PTSD. Carl Johnson, 36, recently trained a collie mix named Ace, who went on to be a calming companion for a little girl with autism. “I used to get down on my hands and knees and act like I was crying,” Carl says, explaining how he’d create possible situations the dog could encounter with the girl. He’s now training Brixx, who used to submissively pee whenever somebody tried to pet him. Brixx is going to a home with a girl who has cerebral palsy. “I have to teach him to stand strong for when she feels like she’s gonna fall,” he says. How does he do that? Carl sighs heavily. “Lots of patience. Lots of patience,” he says. “It’s not easy. Sometimes it’s stressful, but it pays off to see that family with that dog and know how much he changes them.” He also likes that he’s giving the dogs a second chance at life. “Kind of like me,” he says. “I didn’t have any education. Now I’m three classes away from getting my associate in science.”

Carl Johnson with Brixx

The four inmates I interview mention wanting to continue this kind of work when they get released. Doug Hall has two years left of a 25-year sentence for robbery in the first degree and manslaughter in the second. He was the driver at a drug deal gone awry. “I got charged with complicity,” he says. “I wish I never did that. This program right here helps me to stay away from nonsense, to better myself.” The 38-year-old has been in the program since 2012 and has trained about 50 dogs. He keeps a baggie of treats near as he repeats “sit” to Dunkin every few seconds. “This really is a skill, a trade, and I could take it out there and do so much good with it,” he says.

“I had an attitude problem toward staff for a long time,” 38-year-old Michael Johnson says. Brown-haired Apollo sits obediently at his feet. “This has softened me a bit.” He has seven years left on his 20-year sentence. He started the program 17 months ago. “I laid around and didn’t have a purpose, just waiting to get out,” he says. “I’ve done the typical stuff like be a janitor, sweep floors. This breaks up the monotony, and it’s pretty rewarding.”

Michael Johnson with Apollo

The inmates take their dogs outside to the courtyard of the visitor’s area that’s dotted with chairs and tables. All four dogs are on leashes, but two of them play, tackling each other on a patch of grass. The program recently added an agility course for the dogs in one of the yards.

“This is like a resort for the dogs,” Joey Johnson says. “They have it made here. Not that it’s the same as a family setting in a home, but they have it made here.”

Joey Johnson with Kenzi

This originally appeared in the September 2016 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find your very own copy of Louisville Magazine, click here.