Longtime civil rights activist Tom Moffett died on Sunday, May 27, 2018. He was 94 years old. Back in 2016, we took a deep dive into the life of the man in the telltale red sweater. What we found was a story about faith, empathy and dedication. Read on below. —Ed.

There he is again. First or second row, usually. The hearing aids he’s worn since the ’90s don’t help much these days. From behind bronze-framed glasses, dark blue eyes focus on whomever is speaking until, occasionally, eyes slowly drift down, lids following, his head the last to fall, almost wilt, into his hand. He’s not sleeping. Just resting. Then, a charge, a call to action — “African-Americans since slavery have been experimented upon in some way or fashion!” And the hearing aids will catch at least the sentiment if not the words and his head will snap up, give a nod, a smile. He’ll applaud. “Yes!”

Always with the red sweater on. How old is the man in the red sweater? Eighty-something? Ninety? He’s lost nearly all his hair, save for gray wisps and a fuzzy brown patch that survives behind his left ear. Age has dispatched all mechanics to the surface — bones, veins, no youthful pulp left beneath the pale skin that coats whatever spirit flickers so strong that there he is again.

Since moving to Louisville a little over four years ago, I’ve often found myself wondering about Tom Moffett, studying him. Everything I’d attend regarding housing, education, poverty or, really, any social-justice issue, he was there. Everything I didn’t attend, he was there. Sometimes I’d catch a glimpse of him on the news. Oldest guy in the room, the TV cameras love him. (“If I lose track of him, I’ll find him on the news,” a friend of his jokes.)

There he is, June 19, 2014, at a Metro Council budget hearing, looking each council person in the eye, gesturing his hands for punctuation: “This budget reminds me of the saying ‘penny wise, pound foolish.’ The big money is going to stuff we don’t really need.”

There he is at a September 2015 school-board meeting talking achievement gaps between poor minority students and their white counterparts. “These gaps remain unchanged despite decades of effort by JCPS to achieve equity,” he says, his wobbly voice often lifting to a near-shriek. “I have to call that a crime.”

Policies often remain static — it’s all rules and order and “Mr. Moffett, you have three minutes; a bell will sound at two and a half minutes.” Bureaucratic tedium keeps most citizens far away. Not Tom Moffett. He’s been showing up since 1966.

There he was in the late 1960s, marching in south Louisville, where some white supremacists had been intimidating black families trying to move into the neighborhood, his wife having to tell their school-aged daughter that Daddy might not be coming home tonight. He might get arrested and go to jail, but not because of a bad thing; sometimes, people go to jail for doing good.

On a recent hot August afternoon, there he is with his Black Lives Matter sign on West Broadway at a rally, this after holding a Veterans for Peace sign for an hour in the Highlands, pumping his fist every time a car would honk in support.

A former Presbyterian pastor, Moffett’s been described to me by his close friends as a social-justice warrior, a worker bee, even a saint. (Moffett packages his life in far humbler terms.) He is not as well known as some Louisville social-justice icons he worked with for decades who have since passed away, like Anne Braden or the Rev. Louis Coleman. Leading the pack, that’s not Moffett’s style. But he is there, engaged. Moffett often pencils three to four events into his blue pocket calendar that’s always tucked in his dress shirt’s front breast pocket — readings, rallies, an elder counsel gathering, a meeting of advocates for a single-payer health system. “Let me check what I got going on,” he will say to me many times while working on this story.

In the last two or three years, the 92-year-old has slowed down. Just within the last year he’s contracted pneumonia twice, a cough and fatigue forcing Moffett to remain more still than he’s ever been. But when he’s well, there he is again.

In early May, I meet Moffett for the first time. When I mention who I’m visiting to the woman at the front desk of his apartment building, she smiles and purrs, “Enjoy.” Another worker says, “Such a gentleman — they don’t make them like that anymore.” Moffett, who spent most of the last 50 years living in west Louisville, moved to an assisted-living tower near downtown five years ago after falling down some stairs in his Park DuValle condo. In his building, there’s 1940s-era jazz in the lobby. A daily sign advertises such activities as Wii bowling, a ladies’ coffee or Bingo. Walk along the sixth floor, where doors mostly stand bare, maybe a wreath. Until you reach the end of the hall. A sign declaring “I HATE WAR” is taped above a knocker. Below, a colorful poster reads “Love Thy Neighbor” and, in bubbly lettering, lists everybody — homeless, Muslim, black, gay, white, Jewish, atheist and so on. This is Moffett’s door.

He greets me, as he will in later visits, with a kind, open-mouthed grin that reconfigures age lines into smile lines. He’s a spindly 5-foot-11, barely 115 pounds. His long legs, probably coltish in his youth, have stiffened. He sits, one leg crossed over the other, on a green couch that he’s had for 56 years, a University of Louisville blanket draped on the back. Over the summer, his daughter will bring him a new, puffy gray one. (“I was worried I wouldn’t be able to nap on it,” he says. “But it’s working out just fine.”)

His bookshelves have no room for fluff. There’s the Bible, a collection of social justice and historic nonfiction books, Anne Braden’s book The Wall Between, which explores Southern racism. Old Courier-Journal newspapers and editions of the Louisville Defender are scattered here and there. Medicine bottles and mail clutter a kitchen table, and whatever protest signs have just made their way home fill chairs.

This apartment is where I’ll spend several hours with Moffett, talking but often just listening. He warns me on my first visit: “I have a hearing problem that hearing aids just don’t really fix. My brain doesn’t process the sounds as quickly as it used to.” So I keep questions to a minimum. I like listening to him, anyway, the thoughtful reflections scattered, long and wandering. Always interesting. I send a lot of questions by email. Moffett’s quite adept at modern technology. Former Metro Councilwoman Attica Scott was used to receiving emails from Moffett on hot issues like the budget or increasing the minimum wage. But when she received a friend request from him on Facebook, she had to call a mutual friend. “Is this the real Tom Moffett?” she asked. It was.

At first, Moffett seems surprised that I want to write about him. (When introducing me to friends, he hesitates: “This is Anne. She’s writing about — um, me.”) I’ll learn that is classic Tom Moffett, shrugging off much of his activism. “I was never a mover or shaker,” he’ll say. “I was sort of a follower.” And he repeats how “so many African-Americans risked more than I ever did.”

But get out of his apartment, meet his friends, and a more complete history emerges. One morning we visit Mattie Jones, a feisty civil-rights activist and longtime friend. “Tom Moffett!” the 83-year-old exclaims as he walks through the door of her elegant, 105-year-old west Louisville home. “To talk about the contributions Tom has made, especially as a white man,” she says, pausing. “Of course, we (African-Americans) don’t see him as a white man. We see him as a human being who stands for rights and justice.”

“Brave” is one way Jones labels Moffett. “The most impressive thing I’ve ever seen from Tom,” she begins, recollecting an anti-war demonstration at Fifth and Jefferson streets sometime in the early ’90s. “A guy came up. He tried to fight another guy. And Tom, he put himself up as a human shield. Every time this guy would raise his fist and try to hit this other fella, Tom would just move. That was a day that really touched me. He couldn’t get around Tom. He left.”

“You know, Mattie,” Moffett says, chuckling (it’s a distinct laugh, like a gleeful, high-pitched gasp for air), “I didn’t even think about it. That was just instinctive.”

“Tom always stands up,” Jones says, adding a firm nod.

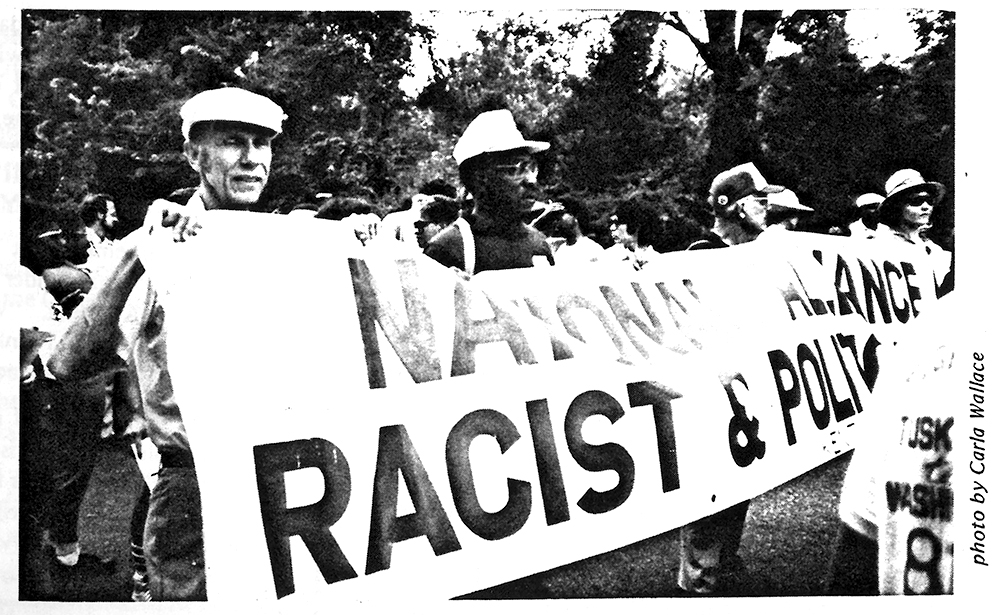

This photo of Moffett (left) appeared in the July 1987 Kentucky Alliance newsletter. Moffett is protesting the death penalty in Montgomery, Alabama.

Perhaps Tom Moffett’s face doesn’t appear familiar. His name might. He remains a regular in the Courier-Journal opinion section. I could probably fill every page of this magazine with letters Moffett has written to the C-J and still some would go unpublished. There’s finger-wagging:

April 19, 1993: Dear Senator McConnell,

It may be foolish for a dyed in the wool Democrat to think I can have any effect on a determined Republican Senator but I feel that I must try . . . THE REAL WELFARE WASTE THAT IS BANKRPUTING OUR COUNTRY IS GOING TO PERPETUATE A LEVEL OF MILITARY SPENDING THAT IS NO LONGER NECESSARY.

Anger at hypocrisy:

March 1991: God places no more value on an American than on an Iraqi. Our nation has never threatened war during the 40-year rape and pillage of black South Africans under the torture and terror of apartheid.

Moffett will scribble pen to paper often, drafting thoughts, editing with slashes. He hands me a packet of such writing one afternoon. Eight pages from 1986 read raw and articulate:

We still have a school system that suspends blacks disproportionately and refuses to investigate whether part of the reason is that white teachers react differently, more fearfully to behavior of blacks than to that of whites . . . unemployed black young people have been held hostage not for one or two years but for decades. The headline always says unemployment rises to 10 percent or it falls to 7.1 percent. The real headline that never gets printed is . . . black teenage unemployment stays at 45-50 percent!

Choosing social justice as a pastime, that’s a slog. Take, for instance, one of Moffett’s major concerns — police brutality. In the months reporting this story, the issue of police shooting black males simmers. Moffett and other local activists have hammered away at this for decades. The organization Moffett most aligns himself with is the Kentucky Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, a group that formed in the late ’70s.

I’ve found Kentucky Alliance newsletters dating back to the ’80s and ’90s calling out police for questionable shootings and beatings of young black men. Plenty of fliers advertising protests on the matter, too. In 1999, the Alliance helped push the Board of Alderman to approve a civilian police review board. But that plan collapsed after the city-county merger. Activists kept pushing. In 2004, Moffett wrote a letter to the Courier-Journal. It begins:

Is Mayor Abramson doing all that needs to be done to stop the string of police killings that continue to fall disproportionally on African American men?

And now here, in mid-July 2016, there’s Moffett unfolding his walker’s padded seat, sitting down outside Louisville Metro Police headquarters, holding a picture of Martin Luther King Jr., repeating dozens of names of minorities killed recently by police across the nation. After names are recited, rally participants, most of them white, are encouraged to step to the microphone and share why they “show up for racial justice.” Moffett shuffles forward with the help of his friend Carla Wallace, who braces one elbow. “I show up for racial justice because 400 years of black resistance and resilience inspires me!” he says. A young, bearded man cheers, “Yes, sir!”

Wallace’s whole body smiles. She gives Moffett a thumbs-up. Wallace, a middle-aged brunette whose entire family is cut from activist stock (her father, Henry Wallace, is remembered as an ardent civil-rights supporter and opponent of the death penalty), co-founded Louisville Showing Up for Racial Justice, or SURJ, an organization that urges white people to do more than just claim they’re not racist. Moffett’s presence, Wallace says, motivates. “It gives people an idea that it is a long road,” she says. “And you never have to think you’re too old.” I will hear a version of this a lot too: “If I ever feel like not coming to something, Tom inspires me because I know he’ll be there. Here’s this 92-year-old taking the bus to get there.”

And that’s the answer to: Why always the red sweater? Age has turned him a bit cold-blooded, yes. And he likes the color red. But Moffett’s been around long enough that he’s a symbol, a reminder to fight injustices, wrapped in comforting Mr. Rogers fashions. “I came to realize it doesn’t hurt to be recognized,” Moffett says.

A young Moffett outside a relative's home in Madison, Indiana

Moffett is the son of a pioneer Presbyterian missionary who helped establish the Korean Presbyterian Church. Samuel Austin Moffett arrived in Korea in 1890, focusing his missionary work to the rural, rugged north, moving permanently to Pyongyang in 1893. There wasn’t another Christian for 150 miles. At first, the missionary was not welcomed, enduring stones thrown at him. He used to tell his children that he was glad he was a thin man — it made him a bad target. But the lanky, blue-eyed man in a black suit and hat pushed on. Korean Christians came to know him as the “looking-up-the-road man,” a visionary who bought 110 acres and built a college, seminary, hospital and churches. Forty-five years later, when he retired, there were roughly 1,000 churches and 150,000 Christian believers. Samuel Austin Moffett is largely credited with that conversion.

The youngest of five boys, Tom Moffett was born May 18, 1924. As a child, he recalls, the family read a chapter of the Bible and prayed after breakfast every day. At night, one of the brothers would occasionally overhear their parents praying for the children, asking that they would grow to be wholly committed to Him. All five boys ended up in some form of missionary work.

For Moffett, the ministry came after a brief stint on a Navy destroyer in the Pacific during World War II — “I wasn’t fit to be an officer; that’s not what I was meant to be” —and graduation from Wheaton College and then Princeton Theological Seminary. He wound up pastoring a church in Four States, West Virginia, a tiny mission congregation posted at a mine camp. For the first time in his life, he witnessed intense division between blacks and whites. Miners of all races were “brothers underground, but when they came out they went their separate ways,” he says. In the four hills surrounding the camp there was a hill for the bosses, two hills for working whites and the fourth designated for blacks. When Moffett encouraged black children to come to the vacation bible school, a member of the congregation protested.

At this point, in the 1950s, Moffett’s Christianity started recalibrating. Preaching salvation, that’s all fine for some. But Moffett felt the itch to do more than holler from a pulpit. “You can say, ‘Lord, Lord!’ But what do you do?” Moffett likes to say.

After the divisiveness in West Virginia, he sought out a position that might allow him to unite blacks and whites. In the early ’60s, he landed as associate pastor at an urban congregation in Kansas City. Determined to welcome black members, he walked door to door, forming friendships with individuals who, on the surface, were wholly opposite to him, a white man of Scottish descent raised in Korea. “Getting to know African-American people as people, black people as people — that has shaped the rest of my life,” Moffett says.

While in Kansas City, Moffett got in on his first “action,” traveling to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, for a week in 1964 with a van full of white ministers supporting African-Americans in their efforts to register to vote, a right that was often thwarted by police or hurdles manufactured by local officials. There were marches around a courthouse, gospel songs at night in a gymnasium where the pastors slept. “It was exciting,” Moffett recalls. “It gave me a taste.”

The church in Kansas City eventually combined with other congregations, leaving Moffett looking for work. He moved to Louisville in October 1966 as pastor of the New Covenant Presbyterian Church. The brick building with concrete pillars hidden by shade trees still stands at 37th and Broadway (though it’s no longer New Covenant). Just a few blocks from the church, Moffett, his wife and two daughters — one in high school, one barely school-aged — lived in the church manse, a boxy two-story home near Shawnee Park.

Moffett in Kansas City with his family: wife Prudence and daughters Margie and Anne

When Moffett arrived, Louisville was more progressive than much of the South. Three years earlier, black-community pressure resulted in the passage of an ordinance that desegregated public spaces. But racism still gripped the city. “The civil-rights gains of the ’60s were largely legal,” Moffett says. “Which were very significant. But they were not societal changes.”

Moffett quickly jumped into the open-housing movement that had arisen in the early ’60s, marching for the rights of blacks to live wherever they wanted, even in the newly developed subdivisions south and east of downtown, spaces popular with fleeing whites. Much of the neighborhood surrounding Moffett’s home and church was falling victim to “block breaking,” a tricky scam of sorts whereby real estate agents would sell one house on a block to a black family. Frightened whites would then jump to put their houses on the market and African-Americans would buy these homes at an inflated price.

One of the open-housing protests (Moffett can’t recall a year) marked Moffett’s first arrest. “I didn’t want them to take my fingerprints,” he remembers. “I was objecting to the notion that I was a criminal because I was standing up for my beliefs.” (Moffett’s been arrested a few times since then, like in 1997 while protesting a lack of minority contracts for the construction of Papa John’s Cardinal Stadium.)

Quickly, Moffett’s connections to the social-justice scene expanded. The late Georgia Davis Powers, the first African-American to serve in the state Senate and confidante to Martin Luther King Jr., was a member of Moffett’s church. She was on the committee that listened to his test sermon and hired him for the job.

Moffett met Anne Braden at a zoning hearing. Braden and her husband Carl were both passionate civil-rights leaders and founders of the Kentucky Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression. They are best remembered for helping purchase a home for a black couple, Charlotte and Andrew Wade, who could not get anybody to sell to them. The action resulted in the Wades’ home being bombed and the Bradens facing charges of sedition. Anne Braden encouraged Moffett and his wife Prudence to join the West End Community Council, an organization working to stem white flight from west Louisville.

Moffett then gravitated toward the efforts to integrate schools. While courts mandated integration in Jefferson County schools in 1973, anti-busing demonstrations shook the city two years later. That’s the year Moffett recalls his only physical harm. As he made his way through the demonstration, an anti-busing protestor slugged Moffett in the ribs. “It wasn’t a hard blow,” he says. “I moved on.” Moffett admits that his social-justice work took priority to his duties at New Covenant. “I wasn’t a good pastor,” he says. “I was interested in a lot of non-churchy things.” He had a hard time galvanizing parishioners to support his causes. Eventually, in 1975, he decided to quit the pastorate altogether, one of the most “surprising” decisions of his life, he says, considering the family he was born into.

Bob Cunningham, a longtime activist who has known Moffett since the early ’70s, calls Moffett “a quiet storm.” The two have marched in who-knows-how-many marches together, sat in too-many-to-count Kentucky Alliance meetings together. “Tom had a way of bringing a room together,” Cunningham says. “He’d think before he spoke. If there was a dispute in the room and people were not connecting on things, Tom could make it so at least we respected each other. He’s a little afraid of hurting your feelings. But he doesn’t have to threaten you in order to get something over to you. And I think that’s what I got from him. You don’t have to yell and scream.”

Cunningham and I are sitting at the Braden Center, a two-story former home with aging white siding on West Broadway that still serves as the Alliance’s social-justice outpost. Over Cunningham’s shoulder hangs a painted portrait of Moffett. Next to that is a framed collection of mug shots — the Valhalla Ten — activists (including Carla Wallace and the Rev. Louis Coleman) who got arrested in the ’90s while protesting a lack of minority workers at the golf club and PGA Tournament. (On a recent afternoon Moffett clapped when he saw it. “Oh, I was out of town that day! That’s the only reason I missed that.”)

Cunningham is thoughtful, funny. “I don’t want (Tom) to leave me,” the 82-year-old jokes. “I don’t want to be the oldest guy in the room.” After about an hour of talking about his friend (like that time Moffett got right in the face of a Klansman!), he pauses. “In a way, I’m glad he’s white,” Cunningham, who is black, says. Moffett’s made a leap. Cunningham explains: There might be a poor black kid on the corner with “the cure to cancer in his mind.” If we don’t get that kid to medical school? What a loss. “That’s what I get from Tom. You’re helping yourself when you help others. I don’t hear that from many white people. Oh, sure, you want to help black people. Well, that’s great. Do you realize you’re helping yourself too?”

It’s early June, the week of Muhammad Ali’s death. Moffett was given tickets to Ali’s Muslim prayer service and invites me along. As we make our way into Freedom Hall I’m amazed at how nimbly Moffett moves. Curbs that I fear his large feet will clip, he clears with ease. The three-pronged cane he clutches, but barely seems to need, claps along with each hurried step. (We’re an hour early.)

The service is in a cold, gray, concrete, hangar-sized space. Children in colorful hijabs chase each other. A pack of dapper men march in with The Rev. Jesse Jackson. Moffett spots a young man in all black limping with a cane. “You know, I’ve had a very fortunate life,” he mutters. Moffett accepts that his time is limited. “Death, for me, isn’t heart-wrenching,” he says, the only exception being when his eldest daughter died at 30 from cancer. He’s not even so nervous about what’s on the other side. “There are passages in the Bible that say, in essence, that heaven is where God is. That heaven is within your heart now. If we feel the presence of God, that is what heaven is.”

Moffett’s recognized instantly — a friend from a local peace program, two women from church — but it’s Ann Reynolds who waves Moffett over to sit next to her. The two met 18 years ago after her son Adrian was severely beaten by a Jefferson County corrections officer, who stepped on the prisoner’s head. The 34-year-old Reynolds died six days later. (The officer stated Reynolds was combative and was found innocent of murder in a subsequent trial.) Moffett, along with other social-justice leaders like the late Rev. Coleman, protested Reynolds’ death for months. “That’s how I met Tom,” Ann Reynolds says. “And he’s had my back ever since.”

Reynolds, a pretty 75-year-old with gray chin-length hair and thick glasses, gets up from her chair to snap photos of the prayer service with her iPad. Reynolds and Moffett volunteered countless hours side-by-side at the Kentucky Alliance, he as treasurer, she as a community organizer. Moffett relishes talking about the Alliance — its actions, its ability to bring whites and blacks together, even if sometimes racial tensions surfaced.

“As a society, we can’t get over the fact that black and white has trouble working together,” Moffett says. “We don’t always agree. Sometimes there’s infighting and that gets personal and someone says, ‘Well, you white people don’t understand!’”

“You white people don’t understand,” Reynolds, who has returned to her seat, echoes, deadpan.

Moffett turns to her. “You were eavesdropping on me,” he says, laughing.

“Sometimes I have to remind myself, I talk about ‘we’ when I talk about black people,” Moffett says. “But I have to be careful about that.”

“See, you been around them so long, you think you’re one of us,” Reynolds teases.

“Well, I am one of you,” he says.

“You are,” she says. “I said you were. I’ve told him he’s black and doesn’t know it.”

“Then again, I have to remember I see through white eyes,” Moffett says, later elaborating, “I can’t ever forget I’m an adopted member of the community. I still exist in a privileged cocoon that the African-American community doesn’t know anything about.”

This whole idea of Moffett’s race comes up often, mostly in jest. Once when a friend was giving him a ride home from a Black Lives Matter rally, Moffett saw the 300-plus crowd spontaneously marching down Broadway. He got so excited in the back seat of the car that he told his friend: “Hurry, put your Black Lives Matter sign in the window!” She teased: “Yes, Miss Daisy.” To Moffett, humans built the race wall; they can knock it down. “We all came from somebody in Africa. Our DNA all goes back to the same place,” he says. “We’re all one.”

After leaving New Covenant in 1975, Moffett joined Grace Hope Presbyterian, a historically black congregation in Smoketown. He still worships there. Moffett can’t hear much of the sermons anymore. But every Sunday he slides into the third pew to the left of the pulpit, tapping his right foot to the organ music and spiritual hymns, even singing along by memory: This is the day, this is the day that the Lord has made . . .

As Ali’s prayer service is set to begin, thousands of Muslim worshipers and curious revelers squeeze together near where the casket will roll through. The density reminds Moffett of the Million Man March, a mass gathering of primarily African-American men (and some women) in Washington, D.C., in the fall of 1995 that intended to display a united, positive side of the black experience. Moffett helped organize a busload from Louisville to attend. (“Only white dude on the bus,” Cunningham recalls, laughing.) Moffett closes his eyes at the memory of the march. “Like something you couldn’t believe,” he says, eyes still closed. “A whole pack of brothers and sisters.”

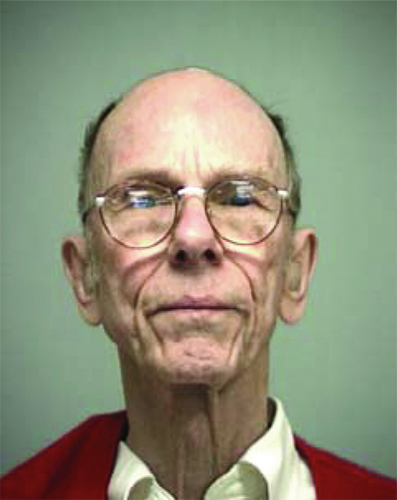

Moffett's red sweater makes it into a mug shot of him

following a disorderly conduct arrest in 2001.

I have a few favorite moments from getting to know Moffett. Here’s probably my second favorite: It’s a hot Sunday afternoon at the Douglass Loop. We’re walking to a Veterans for Peace rally. Moffett’s looking like a true Scotsman, wearing a tartan cap (his second-most recognizable accessory after the red sweater). We pass a yoga studio, which reminds him that he tried yoga a few years back. “It wasn’t for me. No group interaction. I like group interaction,” he adds. When we meet up with a half-dozen other protestors, Moffett slips on his black Veterans for Peace vest, grabs a sign. The others chitchat, harmless catching-up. Moffett commands: “Well, let’s get out on the street.”

This protest is one of those semi-regular small protests, not high on the urgency scale. But for Moffett, action is action. War continues. People suffer. Taxpayer money pays for weapons. So let’s get to it. Longtime friend and Alliance member David Horvath says it’s often Moffett who is “standing up in a meeting urging for massive civil disobedience.” This past fall, Moffett helped rip up blueprints for a Metropolitan Sewer District basin project that would’ve never been proposed for a ritzy suburb but was slated for Smoketown. He did it to show solidarity with concerned neighbors. Plans were soon scrapped.

Moffett’s role as peaceful agitator and 2007 inductee into the Kentucky Civil Rights Hall of Fame is a bit of a plot twist when learning more about his early years in Korea. “We lived a totally privileged life,” he says. Being a leader of the church, Samuel Austin Moffett’s house was among the biggest on the missionary compound. “Gobs of rooms,” Moffett says. There was a basement with a coal-fired furnace and running water, a front yard the size of a soccer field, where the Moffett boys played endless softball games. There were chestnut trees and strawberry patches, a clay tennis court (Moffett played well into his 80s), tulips, parallel bars, a lively Irish setter. In the half hour between supper and bedtime, young Tom would crawl on his dad’s lap in the living room and hear bedtime stories, a fire crackling if the night demanded extra warmth.

Every summer, the Moffetts would vacation on a simple houseboat made up of two rooms and a thatched roof. Kids would sleep on straw mats on the floor and spend days swimming and exploring caves with the houseboat parked at a sandbank. When Tom was young, his father would sometimes throw a stick in the water and then yell, “Tommy overboard!” All able bodies would dive in, practicing a rescue just in case Tom fell in.

Six or seven Koreans were in charge of pulling the boat up the Taedong River. They lived on the houseboat as well. “We lived the life of Riley,” Moffett says. He thinks the journey may have been as far as 50 miles. (The boat then floated back downstream, with the crew packed into small quarters on the boat.) “I do remember some uneasiness between us and the crew,” he says. “One thing that helped me pick that up was my mother was not as comfortable with the crew as my father. And she didn’t want me to associate with the crew.”

Moffett remembers his parents as conservative Republicans. They didn’t drink alcohol (neither does he) and wholeheartedly opposed President Roosevelt’s New Deal. One afternoon Moffett hands me a July 1954 issue of Presbyterian Life. A picture of his father — graying, serious, reading a newspaper — is on the cover. When Moffett was born, his mom was 45 years old and his dad was 60. He died when Moffett was 15. Great influences last and last, though, through the years, over generations, creating parallels. In the pages, I read a story about Samuel Moffett as a young missionary needing to borrow a house so he could bathe in a tin tub he carried: “There followed quite a hullaballoo as the Koreans gathered, wetting the mulberry paper windows (which were not transparent) with their fingers and poking little holes — all to discover whether or not the foreigner was white all over.”

On the July evening I meet Moffett’s daughter, Anne Thompson, she’s nearly bursting. She just has to tell me something funny before she forgets. “I came out of my childhood with the impression my daddy had fixed everything….I thought, you know, all those civil rights were fixed,” she says, smiling. “It wasn’t until my early teenager-hood when I realized he had not. That’s just how a child thinks of their dad, especially a dad like mine.”

Thompson, a friendly 54-year-old who shares her dad’s blue eyes, says that even as a young child she knew her father was tackling big, important matters. “Like there were things in his life that were more important to him than us. But not in a bad way,” she says. “He had a mission.” She never felt unloved. Moffett “spoiled” her, often trekking over to the Fontaine Ferry amusement park for a swim. (Moffett tells me he always felt guilty using a park that for years excluded African-Americans.)

Thompson remembers her father going off to meetings, writing sermons at the kitchen table near a large poster of Martin Luther King Jr. When two girls from down the street saw the poster in the Moffett house, they called Thompson “a nigger lover.” It only happened once. But by six or seven, other difficult concepts entered her world. She has recollections of her mom explaining what a Molotov cocktail was, why that was a scary, awful thing, why someone would stake a burning cross in someone’s yard. That’s why daddy went to a march. Thompson works as a nurse at the Phoenix Health Center for the Homeless. “I’m sure I wouldn’t have gone into that kind of place were it not for my dad,” she says.

When Thompson was about 10, her parents divorced. (Moffett admits he married his wife in college more as a way to prep for life as a pastor than out of passion. “I went searching for a wife my senior year,” he says, laughing. “I wouldn’t recommend that.”) Mom lived in the Highlands, Dad at an apartment in Shawnee, then over in Park DuValle. Juggling single-parenthood and social activism led to one minor sitcom-type debacle. “I’m going to get in trouble with my daddy for this,” she begins. “He was always going to one thing or another. And I called him at church (one night) and said, ‘Daddy, did you forget to pick up my babysitter?’” Thompson says with a laugh. “Daddy’s always thinking of bigger things.”

This time in Moffett’s life, the ’70s, was full of change. When Moffett quit his pastorate, he went back to school and eventually became an accountant for the Park DuValle Health Center, a job he held for 40 years and then some. He retired in the ’90s, only to be recruited back in the early 2000s after some troublesome bookkeeping plagued the center. “It’s certainly legit to earn a living being a pastor,” Moffett says. “But I just wanted to be Tom.” Being “Tom” has become harder as Moffett has aged. “He’s still got more energy than I do,” Thompson says with a chuckle. “(But) when your 92-year-old father says, ‘Every year I seem to have a little less energy and I just don’t understand that…,’” Thompson says with a sigh.

Six years ago, when it was time to move to assisted living, Moffett made it clear to his daughter that he didn’t want to end up in some East End fancy home for white folks. He’d be miserable there. He needed a place on a bus line, important because he no longer drives. The tower he moved into is a good fit. This past spring Moffett organized a party for a streaming Bernie Sanders event, handing out fliers to residents. He had a couple takers.

“I suspect he didn’t tell you about the time he got mugged,” Thompson tells me. He had not. A few years ago, Moffett was leaving the Braden Center, waiting for the bus. It was dusk. A man asked him for money. Moffett brought out his wallet. The guy grabbed it, pushing Moffett onto the sidewalk in the process. “We made a trip to the ER and did lots of X-rays,” Thompson recalls. “He landed on that bony hip of his.” Everything was OK. But friends and family urged Moffett to stop giving money on the street. “He put his foot down and said, ‘No,’” Thompson recalls. “‘I’m not going to say I’m not going to give people money again; I’m just going to do it in a safer way.’” Now Moffett carries a few spare dollars in his pocket.

Thompson pauses for a moment, reliving the whole incident. “He doesn’t want to give things up for what he considers one bad apple, one bad experience,” she says. “Things like that are difficult for my dad to accept emotionally, I think, because he’s invested so much of his life and energy into trying to improve things for African-Americans and trying to change the minds of white people. So when a black person does something that’s going to cause the racists to say, ‘See, we were right,’ it hurts him. He always wants to look on the best side.”

That reminds me of a story Moffett told one morning while I drove him around west Louisville. Back in his pastoring days, New Covenant had a great basketball gym that kids would often break into to play in. “Very early in my pastorate, the police caught (some kids) doing it and called me,” Moffett remembers. “I didn’t want (the police) to take them down and book them. But they went ahead and did anyway. So the next day I went down and refused to press charges. About 40 years later I was climbing on a bus in the Park DuValle area and the bus driver said, ‘I know you! I’ll never forget you! You got me out of jail!’” Moffett gleefully laughs at the memory.

One day Moffett wonders out loud if maybe his desire to fix hurting people amounts to co-dependency: He likes the way pleasing others makes him feel. Whatever reason, Christie Swan Kelly adores the man she considers a pseudo-parent. She occasionally dabs tears when talking about Moffett. The two met 20 years ago through the Alliance. At the time she was a single mother in her early 20s. She had grown up in the Park Hill projects and was estranged from her own mom. Kelly describes herself back then as “angry.”

Moffett embraced Kelly. And her children. When two of her sons were charged and convicted of serious crimes, one of them for manslaughter related to a drug deal gone bad, Moffett sat through the trials, visited the young men while in the county jail, writing them letters once they were sent to prison, a gesture he’s made with other inmates as well. You are important. I care about you.

Moffett’s the one who showed up at the hospital when an ex-boyfriend hit Kelly in the head. “I never believed in saints,” the 45-year-old with dark skin and dimples says. “If I did, Tom’s the closest person I can say that can meet that criteria.” Moffett encouraged Kelly to go to college, fulfill her dream of becoming a teacher. He put her on his car insurance, managed her money, sat by her side at his computer (because she didn’t have one) and nudged her not to give up when challenging assignments flustered her. “He carried me,” Kelly says. Moffett let her move into his condo when he moved to assisted living and even took out a loan to help pay for her school. Some of Moffett’s friends and family worried he was being too generous. “She had such a lack of love and support in her life. I was her last hope under God,” Moffett says. “And God had not really told me to stop yet.”

A few years ago, Kelly was hired as a middle school teacher in Jefferson County. “A load has lifted off of me,” Moffett says, “because if I die tomorrow, she’ll be a much different person than she was.” This past Father’s Day, Moffett, dressed in a gray three-piece suit and crimson tie, walked Kelly down the aisle on her wedding day.

Moffett and a friend at the 2015 Pride Parade. Photo courtesy of Sonja Farah deVries.

Bright balloon plumages, as colorful as Skittles and fanning out like tentacles, keep hitting Moffett in the face. We’ve made our way to the Pride Parade on a Friday in June, and around us skin and beer and Rihanna music swirls. Moffett glows, his open-mouthed smile frozen in place, his blue eyes grazing and gazing. This is my favorite day with Tom Moffett.

It’s a muggy night. The parade’s a bit late starting. Moffett sits on his walker’s padded seat, a tattered Black Lives Matter sticker stuck to his checkered dress shirt. I was so worried about him walking in tonight’s parade that I forced him to hydrate beforehand with a cup of water from McDonald’s. But he appears to me to be the happiest 92-year-old in Louisville at the moment. “Anne,” he says, “there’s a part of me that positively wishes that the movement for African-Americans could move as fast and as far as the one for gays and lesbians. But there’s something about it that’s just a different story.”

Moffett’s a longtime ally of the Fairness Campaign, even serving as a marshal in one of the first Pride Parades. He often wears a Fairness pin on his red sweater. But in the late ’80s and early ’90s, when the local gay-rights movement was picking up momentum, Moffett struggled. Carla Wallace, who co-founded the Fairness Campaign, remembers overhearing a conversation Moffett had with another Christian reverend on a bus that was headed to Alabama for a protest. “(They) were sitting together and Tom was like, ‘You know, I have questions,’” Wallace recalls. “He’s like, ‘How does it fit with our faith?’”

A tug between Christian beliefs and human equality. You can say, ‘Lord, Lord!’ But what do you do? Moffett dove in, befriended those in the gay community. “I was coming to realize they were ordinary people. A lot of them were as forward-looking as I was. When someone called me and asked if I wanted to be a marshal in the parade, I took a gulp and I said yes. I had to stand up for their rights.”

A man with a Quaker-type beard and straw hat stands behind us.

“You show up everywhere,” he says to Moffett. The two have met at various events. The man, a white reverend, pastors a primarily black church in west Louisville. “I have to ask you a question,” Moffett begins. “Have you had any luck getting members of your congregation to come out and support something like this?”

“Most of them don’t have a radical faith,” the reverend answers.

“Well, they pay a higher price for doing it,” Moffett replies.

“Have you ever asked for your FBI file?” the reverend asks, indicating that his is quite thick.

“No,” Moffett says, his voice cracking into a surprised high octave. “I need to do that!”

“Tom!” Carla Wallace yells, jogging over. She strokes his shoulder. “The parade is complete.”

Another voice from far away shouts: “We’re moving!” A siren wails. The mob presses forward. Moffett gets going, youthful bodies speeding past, many that he’s never seen before, a thrill for him. Moffett grows quite tickled at the sight of younger generations embracing social justice. A couple times this summer after an event, he’ll say, with a smile, “I didn’t recognize anybody. That’s wonderful.”

Tonight, Moffett plans to walk the whole route. The sun hides behind downtown buildings, rays of light forming a crown between rooftops and blue sky. Moffett doesn’t say much, but he marvels at the 15,000-plus people out to support the LGBTQ community a week after the shooting in Orlando that killed 49 people at a gay nightclub. He spots a sign: GOD LOVES YOU. SHE THINKS YOU’RE FABULOUS. “I like your sign!” Moffett says, voice almost a shout.

Moffett’s been a perfect companion for this past summer, one that seemed to hit with daily news tragedies— terrorist attacks, police shooting citizens, citizens shooting police. I’d occasionally mention the latest horror. He’d shake his head but would never dwell in the dark. “The human spirit, I’m convinced — with its divine spark or whatever you want to say — is invincible,” he says. “I don’t know if the world will go down with a nuclear catastrophe, but the human spirit is invincible. I just can’t look at the negative side and say it’s going to win.”

Cheers and whistles fill our ears. Men in kilts run by. A woman in a red headband pats Moffett’s shoulder: “You are the cutest thing here!” she exclaims. Bubbles waltz in the air. Near First Street, Moffett starts to slow down, his feet dragging more with each step.

A longtime friend of Moffett’s, David Horvath, who often drives him to events, has noticed something about Moffett recently. “He’ll get into the car and be just tired,” Horvath says. “What he’ll inevitably say is, ‘You know, I feel like I can’t accomplish anything some days. Then I realize I just have to do more.’ And then he says the thought of doing more and attending more things actually helps him feel less tired and more alive.”

By Second Street, Moffett lets out a weary, “Oh, boy.” A woman runs up and drapes green beads around his neck. “Anne, I think I need to call it quits,” he says, a few blocks shy of the parade’s finish. I run to get my car, and as we head home he sighs a pleasant sigh.

“Wow,” he says. “That just worked out beautiful.”

This story originally appeared in the October 2016 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.