Photos by Jessica Ebelhar

Magic. That’s how Churchill Davenport describes the Kentucky College of Art + Design at Spalding University.

Davenport, the school’s founder and chancellor, grew up here but spent most of his years away studying and teaching at what many consider top art schools: Yale, in New Haven, Connecticut; New York City’s Pratt Institute; Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), in Baltimore. He’d meet students from Kentucky and wonder why they all decided to come out east to get a good art education — and why few returned to Louisville. On trips back here he’d think: Louisville is an art town. Louisville needs — deserves — an art school. Around 2007 he was in town visiting his mother and told her, “I’m gonna start me up a little college.”

A white-haired 73-year-old in classic professor attire (blazer, jeans), Davenport tells the story on an August afternoon at the Spalding campus, just south of downtown. He first came to Louisville in the 1950s when his father, the Rev. Stephen Davenport, moved the family from Boston so that he could head St. Francis in the Fields Episcopal Church in Prospect. The minister went on to found St. Francis School. His name appears in many New York Times wedding announcements. The St. Francis congregation included the late Brown-Forman chief executive Owsley Brown II. Another Brown, Laura Lee, was in the choir. Churchill Davenport’s wife, Laurie Fader, says that his family founded New Haven in 1638. The ministry goes back 13 generations of Davenports. “He’s got it in his blood,” Fader says.

Davenport didn’t take the divine path like his father and brothers did. At 21, he was still in high school, suffering from dyslexia long before it was a widely recognized disorder. But he felt he could understand art. “Just all of a sudden I’d bump into Picasso and — whoa, what’s this all about? I’d go to shows in Baltimore and New York and I’d bump into Cezanne,” he says, before casually explaining his family’s connections to the upper echelon of the art world: “My mother knew the Whitneys and stuff.” He ended up attending MICA in Baltimore, where he watched the school’s president at the time, who happened to be from Louisville, grow that campus from one to 30 buildings and revive a whole section of town.

Photo: Founder and chancellor Churchill Davenport.

Ever since Davenport got the itch to start his own school, he’s seemed to do nothing but preach. His mission is twofold: create an art school as a regional hub that competes with the biggies — the ones that art-minded kids across the country aspire to attend, such as the Rhode Island School of Design, Savannah College of Art and Design and others in art hubs like the East and West coasts and Chicago; and make the school an open door for all students who seek a creative practice, regardless of academic achievement or socioeconomic status. “The thing about art,” Davenport says, “I think of it like prayer, right? Anybody can pray.”

Davenport called up every potential backer in Louisville that he could. “They’d say, ‘Sounds cool, Churchill, but starting a college is kind of a hard project,’” he says, his eyes twinkling at his brashness. He met an artist named Bryce Hudson, who had a space in Portland and invited his artist friends to come hear Davenport’s spiel.

“I got a call from Bryce,” says Skylar Smith, who was teaching at the University of Louisville and Jefferson Community and Technical College at the time. “He said, ‘There’s this guy Churchill Davenport in town,’ and I’m like, ‘First of all, is that a real name?’” The lights in the building weren’t working, so the group of about eight sat in the dark on the floor and had a conversation.

The year before, 21c had opened. Developer and filmmaker Gill Holland had recently come to town after marrying a Brown and was helping transform East Market Street into NuLu, a district with new galleries and restaurants. The New Center for Contemporary Art sprung up (in what’s now Revelry). There were rumblings of an addition to the Speed Museum dedicated to contemporary art. “You know, they always say Louisville’s weird,” Davenport says. “I don’t quite go for all that. It’s too simple for me. But it’s a crossroad. There’s a lot of curious people here and there’s a yearning.” To Smith, who attended MICA and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Louisville had been a performing-arts town, but not until that point in her life did it seem to have any contemporary visual-art flair. Having gone to the art schools that modeled Davenport’s vision, Smith saw “the dream,” as many at KyCAD describe it. “Every person at those schools wanted to be an artist,” she says. “No one was majoring in anything else but art. There were a million majors, but all within the visual-art discipline. No Greek system. It’s a different vibe. I was like, ‘I would love to teach at a place like that.’”

Photo: KyCAD sculpture class.

Davenport didn’t have the business acumen to launch a school, so he reached out to his networks and found Kasey Maier. Maier worked in banking and had suffered through the financial crash of 2008. She had been jobless for nine months when a family friend, Tom Pike, who founded St. Francis High School, mentioned that Davenport had been calling him looking for a business operations person. Maier reached out blindly. After a couple meetings, Davenport told her he’d hire her to get the school off the ground — only he didn’t have any money. It didn’t take but a day or two for him to find a donor. Maier says that she and Davenport drove out to Harrods Creek one afternoon to get on a guy’s houseboat. They walked in and four or five men were sitting there with their bourbons. Maier grew up on a houseboat. Her dad was connected in the “river rat” world, so she mentioned that to a guy and they ended up knowing a lot of the same people. “And that was it. That was the selling point,” she says. “It wasn’t about my skillset or anything like that.” The next day Davenport called her and said the guy agreed to pay her salary for six months.

In those early days, Maier and Davenport would work out of Maier’s house in St. Matthews. She’d have coffee ready and they’d say “Who do you know?” and build a database of names — artists, wealthy folks, movers and shakers. “The next thing you know, I got 200 names,” Davenport says. They’d meet with anyone willing to spare some time, Davenport’s pulpit often being a coffee shop. His childhood friends Owsley Brown II and Laura Lee Brown backed his idea, as did Owsley’s son Owsley Brown III, and Davenport’s cousin knew Humana founder David Jones. “I didn’t realize he had this whole friggin’ Humana situation, but he was a really nice man and he gave me some money,” Davenport says.

“I guess knowing these wealthy people is helpful,” Davenport says, often projecting a kind of nonchalance when mentioning his connections to influential people, “but I don’t think — once you meet (Owsley Brown II’s son) Owsley, he’s a spiritual character. Laura Lee is. They’re all like that. They’re magical people and they’re into the arts.”

Skeptical of the school’s potential for success, Davenport’s wife remained in Baltimore while he’d go back and forth between cities. “Churchill kept saying, ‘Come out.’ I said, ‘No way!’” Fader says.

“I had about a hundred bucks in my pocket,” Davenport says. “I was bumming money off my brother to come here.” He says his being gone all the time was hard on him and his wife. “She would say, ‘What about some income?’”

In 2009, 21c owners Laura Lee Brown and Steve Wilson offered Davenport, Maier and Smith, who had come on staff, office space in the basement of the building next to the hotel for one year rent-free. Davenport lived there for about six months. Owsley Brown III, a filmmaker and producer of the Festival of Faiths who splits his time between Louisville and San Francisco, picked up on Davenport’s floating lifestyle and offered him space in the Hadley Pottery House on Story Avenue. “He gave me this gigantic mansion,” Davenport says.

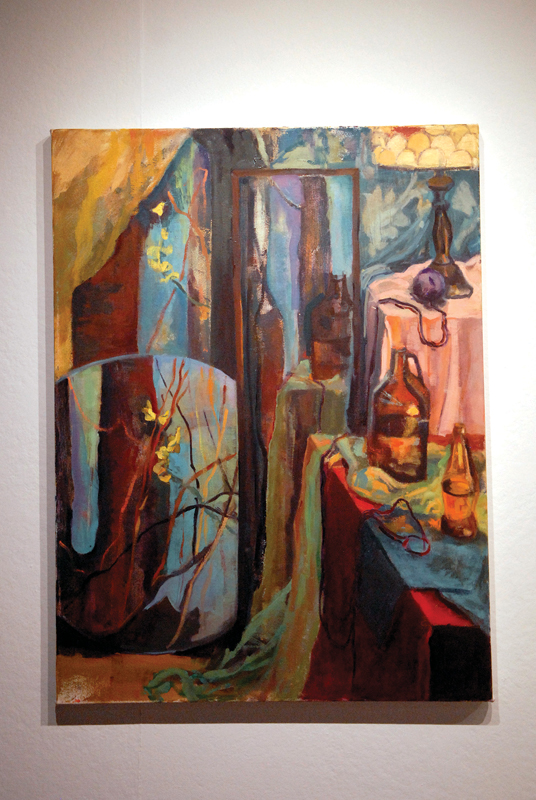

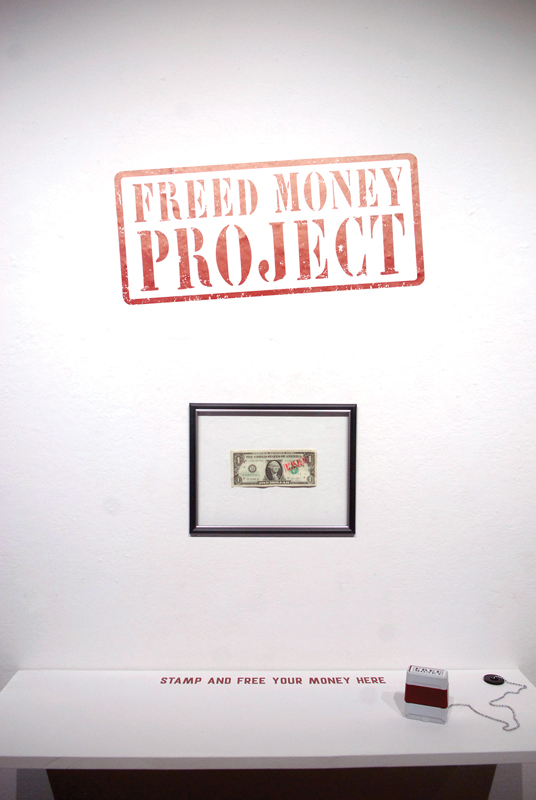

Photo: Art by Anthony Sweeney from KyCAD's 2017 senior thesis exhibition.

Maier, Smith and Davenport spent a year applying for nonprofit status, which they needed to be able to get donations, as most donors don’t like to give much money if they can’t write it off on their taxes. They named the school the Kentucky School of Art (KSA) to broaden its identity beyond Louisville. They’d host potluck dinners, anything to spread the vision and raise money. Maier remembers lining the walls of that basement space with white paper and asking guests to draw their vision of an art school. The result was “some funky-looking stuff, some spaceship-looking stuff,” Maier says, “but it was very much about open spaces and community.” The team held community art classes and portfolio prep for high school kids, looking to attract potential students. Davenport brought in well-known artists, such as realist painter Bill Bailey and installation artist Judy Pfaff, for lectures and critiques. “I know famous people in New York. I know Chuck Close,” Davenport says of the renowned artist. “I would call them up and say, ‘You wanna come down to Lewis-ville and help me out with something?’” The crew made bumper stickers that read: “Love an artist” and attended the holiday festival Bardstown Road Aglow. Davenport says, “We were like a marching band walking around — ‘We want an art school.’”

It’s often hard to tell whether Davenport is joking or being serious. He seems to embellish some elements and downplay others. (“I’m a character,” Davenport says.) “When you listen to Churchill talk about the dream, nobody else could do that,” Maier says. “It was so much from the heart, about him and how he learned. Some of these young artists struggle in a big system. They look at U of L and go, ‘I can’t do that.’ Churchill could talk their language.”

According to several sources, there were naysayers in the art community. “Churchill would get upset,” Maier says. “I used to tell him, ‘Put your blinders on. Cover your ears. Focus forward. In three years they’ll all want to be your best friend.’”

Owsley Brown II, who died in 2011, helped Davenport hire a consultant to develop a feasibility study, which concluded that to become an accredited institution they would have to graduate several classes of students — and nobody’s going to a school where they aren’t getting credits but have to pay tuition. Their best option would be to partner with an existing university. In 2009, a KSA board member who knew the then-president at Bellarmine University started discussions with the school about partnering. By several accounts, a deal looked promising.

Prepping for the first official year, Maier and others cold-called high schools, seeking permission to make presentations to classes, and they’d meet with potential faculty. Maier, whose son went to an art school in New York and has gone on to work as a video-game artist, worked to soothe parents’ fears of the impracticality of an art degree — not to mention one coming from a school with no history or reputation.

Photo: Art by Edward Taylor from KyCAD's 2017 senior thesis exhibition.

By spring 2010, Bellarmine had officially declined. “We were impressed with the concept, but ultimately concluded that it wasn’t the right fit for us,” the school recently noted in an email. (The school’s president at the time, Joseph J. McGowan, has since died.) “All three of us were sitting there one day and were like, ‘Oh, my gosh. This whole thing is about to fall apart,’” Maier says of herself, Davenport and Smith. “It really felt like it was just sucking down the drain.”

Maier fired off an email to Joyce Ogden, an artist and professor who has worked at Spalding University, a 200-year-old private college, since 1993.

A little history: In high school, Ogden moved to town with her family from Long Island. While her sister went to an art school in New York, she says, “That to me seemed stifling in some ways. I wanted to go somewhere where I could figure out completely on my own what kind of artist I was without that pressure or influence of the city.” In the early 1980s, she attended what she calls the “funky” Louisville School of Art, an independent entity that had been around in some form since the late 1920s and offered a bachelor’s degree in fine art. The school, predating U of L’s art program, went through several partnerships, including one with what is now the artist outreach organization Louisville Visual Art. Gordon Brown, the retired president and CEO of the Home of the Innocents, who is on KyCAD’s board, also attended the school. Over the years it moved from downtown to Anchorage and back downtown. By 1983, according to the Encyclopedia of Louisville, decreasing enrollment and increasing maintenance fees forced it to close and become absorbed by U of L’s Department of Fine Arts, which was founded in 1937.

Photo: KyCAD introductory 3-D and sculptural process class.

Ogden says she sensed that the city couldn’t support that kind of art-focused school at that time, but that over the next couple of decades she saw the city grow. “I’m like, ‘The city needs this. The city can handle this now,’” she says. She arranged a meeting with Tori Murden McClure, who had recently become president at Spalding. Maier and Davenport went to the meeting thinking they were just going to propose the idea, then were surprised to see a table full of lawyers and recruitment and financial-aid officers. “(Tori) took a blank notepad, pushed it across the table and she said, ‘You write it and I’ll sign it.’” Maier says.

“I have a soft spot for trying to do things that everyone else says is going to be impossible,” McClure says. “I just fell in love with the notion of: Here’s this madman who hasn’t a clue what he’s asking.” (Davenport says of McClure, who famously was the first American to row solo across the Atlantic Ocean, “She said she rowed a boat across the ocean. I can’t quite believe that one. It’s kind of crazy.”)

“You can’t afford — literally afford — to spend $40 or $50 million that you would need to start from scratch,” McClure says. “Campus safety, IT, dining, dorms, student life — all things a school needs to become accredited as a separate institution.”

While Spalding, with its business, teaching, nursing and several other majors offered to its 2,200 students, appears to be very much a practically oriented school, McClure says that Spalding’s MFA-in-writing program set an example for how the art school could succeed. She was a trustee at Spalding in the late ’90s when the program was being proposed and she voted against it because she thought it was “off-brand.” “I’ve never been so proud to be wrong,” she says. She got her undergraduate degree at Smith College in Massachusetts, a master’s in divinity at Harvard and a law degree at U of L, but calls getting her MFA at Spalding “the academic high point” of her life.

The agreement from the beginning was to get the art school up and running — as a department of Spalding by all legal and technical definitions — to a point where Davenport and the staff could re-evaluate whether the art school wanted complete independent accreditation, to remain an art department or to find some sort of independent-while-still-partnered middle ground, which several other art schools around the country have done.

A word on art schools and departments: At 400 students, U of L touts having the largest studio-art program in the state. Studios for its budding MFA program are under construction in the Portland neighborhood, across the way from where Louisville Visual Art now operates. U of L’s is a department, rather than a division like the University of Kentucky’s College of Fine Arts, which includes performing arts. There are two main accrediting bodies that most art schools want on their name: National Association of Schools of Art and Design and the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design. The AICAD schools: MICA, Pratt, Rhode Island School of Design, Art Academy of Cincinnati — around 40 schools total across the U.S. NASAD accredits closer to 400 schools, including some AICAD members, plus four Kentucky schools: Morehead State University, Murray State University, Western Kentucky University and UK. Some schools, such as Yale and Savannah College of Art and Design, which was founded almost 40 years ago and has made a name for itself among artists, are accredited by neither. Then there’s the difference in tuition. Most of these highly regarded programs cost $35,000-a-year-plus. KSA set its tuition at $24,000, with the assumption that most students would receive financial aid. U of L tuition for this school year is $11,000 for in-state students.

Davenport and those working with him weren’t thinking in terms of an art department, though. McClure told him: “Louisville needs an art school; Spalding does not need an art department.” That’s not to say that nothing was in it for Spalding. To McClure, the art school, it seemed, would further inform the growth that the school and neighborhood had been experiencing. Spalding, mostly situated on urban asphalt, is in the midst of an aggressive greening initiative, 7.5 acres of it in the form of sports facilities for its growing athletics department. It has acquired new buildings and torn down dilapidated ones. It has updated the struggling heating and air systems — all while crawling out of the $14 million debt that McClure inherited.

Photo: Art by Sam Adair from KyCAD's 2017 senior thesis exhibition.

Spalding had vacant space in an old science building for the art school to use. Maier and Smith remember going over, peeking in the windows and seeing dead things in jars. Gurneys sat unused. Davenport’s son ripped out affixed tables and sinks. (Both of Davenport and Fader’s children live in Louisville. Their daughter majored in sculpture at MICA and their son attends the U of L Speed School of Engineering.) Friends and family painted the walls. Maier was able to get some furniture donated and found a couple of inexpensive Moroccan rugs at a yard sale to go in Davenport’s office. One room had partitions with curtains from a nursing class. A maintenance guy offered to remove them, but Maier told him, “No, don’t take them down. This is perfect!” In the fall of 2010, those would become the studio spaces for the first class — three students out of the 25 or so high schools visited.

After some convincing, Laurie Fader, who has taught at Yale, Pratt and MICA, agreed to come down, help build the curriculum and chair the department. The way Spalding is set up, classes are arranged in seven sessions per year, rather than two semesters, so classes are described as fast-paced and challenging. Art students would spend three hours a day in a studio classroom.

For the first couple of years with Spalding, accreditation remained in question and the school wasn’t even sure if the students were going to get a bachelor of fine arts degree. They knew it most likely would happen, Smith says, but she calls those first students “totally brave.” The original degree was a bachelor of arts under Spalding’s School of Liberal Studies as an interdisciplinary degree with a concentration in art. Courses included light, color and design; drawing; three-dimensional design; four-dimensional studies; several electives; and a senior thesis/exhibition.

Steph Parks found out about the art school through her sisters, who attended Spalding. Parks originally started college the fall after graduating from high school, in 2007, but it wasn’t a right fit and she had some personal events pop up that led her to drop out and work instead. The only thing she cared about at the time was making art, so she decided to apply to what was then still KSA. She submitted a portfolio of mostly digital photography and a couple paintings. She went in for a portfolio review and got a tour of the facilities. “At the time I was in wonder,” she says, mentioning how she thought the converted chemistry labs were cool. The admissions process wasn’t as rigorous as she expected — the school wanted to beef up its enrollment. (Davenport jokes that “120 applied and we accepted 140.”)

Her first year, Parks says, professors seemed well-versed and pushed her hard — often having her redo her work completely. “It was a little hurtful at first, but I was producing better art,” she says.

Behind the scenes, McClure struggled to be a hands-off president and let the art school flourish while still keeping it in line with regulations. “I remember one of the early days I was furious with Churchill,” McClure says. “I can’t even remember what it was about. I stomped across the street and I was gonna give him a piece of my mind and I sort of skidded to a stop at the doorway of a classroom. Churchill was teaching and those students were hanging on his every word. I was like, ‘OK, that’s what this is about.’ I sort of hung my head and turned around and came back to my office.”

Davenport soon was named president. “Lots of folks at Spalding really bristled at that,” McClure says, “but honestly, I thought, well isn’t he cute.” She explains that the title went with the nonprofit component of the school and was more of a marketing effort. In terms of the Council on Postsecondary Education, in terms of Southern Association of Colleges and Schools accreditation, McClure says, “It was Churchill a little in costume. I was OK with that. It certainly helped with the ability to raise funds for the school of art.”

Not all has been cute and rosy. In 2013, Maier left. Davenport wouldn’t say exactly why, but Maier says it got too tough to work with him. “He would come in yelling at us over nothing, and Skylar and I were working our butts off,” Maier says. She says he’d sometimes promise scholarships or jobs without proper procedure or considering the finances. She says she would then have to clean up the mess and get yelled at for it. It got to the point where she spent most of her time looking at transcripts and managing recruitment. “One day I thought, you know what? I’ve become a school administrator. We went from startup nonprofit — I just thought, this isn’t what I want to do.” (She is now the executive director at Waterfront Botanical Gardens.) Until I mentioned Maier to Davenport, she didn’t appear in his telling of the story. Even though the two didn’t part ways on the best of terms, he says, “Without Kasey Maier, there wouldn’t be a KyCAD. She was dynamite.”

Photo: Art by Brittney Rice from KyCAD's 2017 senior thesis exhibition.

For Parks, Maier’s exit caused the school’s climate to change. She saw Maier as a “mom figure” who organized social activities for students. Accreditation wasn’t solid. Of the 30 students who showed up at orientation her freshmen year, half were gone for various reasons by the second year. “I noticed that the class before us were still kind of like hanging in there but not really,” she says. (Less than a third of students who enter U of L and Spalding graduate in four years.) Furthermore, Parks had taken a photography class and decided that was what she wanted to fully pursue, but the school only offered a couple of basic courses. “I’d found out that U of L had toy camera photography, alternative and historical process photography, experimental — all of this stuff,” she says. She transferred and got her degree at U of L — having to start over because her credits wouldn’t transfer due to Spalding’s different schedule. She’s now in grad school for social work, pursuing a degree in arts administration.

For other students, though, the school clicked. One kid, Edward Taylor, came in with the intention of using the school as a launching pad to get into a reputable out-of-state art college. “Just a year,” Taylor told the staff. Taylor graduated last spring with a focus on fashion design (which fell under the school’s current interdisciplinary sculpture concentration) and has since been interning with a local fashion designer.

By 2014, it became clear that the art school was struggling without a business-minded leader. “I’d get a new board member and say, ‘Can you give me a little $20,000? I gotta make payroll,’” Davenport says.

One day, businessman Terry Tyler went to lunch at the home of Bill Blodgett, a lawyer, early supporter and board member. Len Moisan, president and CEO of the fundraising organization the Covenant Group, was there. “So I grabbed my wallet as soon as I walked in,” Tyler says. But what they were really after was filling a job. “Churchill said, ‘I’ve been through 46 payrolls. I can’t do it anymore,’” recalls Tyler, who had retired after 35 years at Mercer Human Resource Consulting. At first he declined.

Turns out, his and Davenport’s mothers knew each other — they’d met at summer camp in Maine as kids. “There was some magic there,” Tyler says. “I realized this is a once-in-a-lifetime deal for Louisville, Kentucky.” Plus, he spent a good part of his time working with underprivileged kids. The school’s mission, he says, “really grabbed me.” Tyler became the president, Churchill the chancellor. “Again, titles that are not appropriate in an art department at Spalding,” McClure says. (During one interview I ask Davenport, who isn’t teaching this year, what he does all day. Communications director Cary Willis interjects, “He chancells.” The room of about four KyCAD staffers laughs. Events and marketing manager Kevin Wilson calls Davenport the school’s “spiritual advisor.” No matter his title, Davenport remains one of the school’s biggest fundraisers.)

In the spring of 2015, five years after the original class began studies, the school saw its first graduating class of nine (a mix of students who began classes in the school’s first and second years). The following fall 65 freshmen entered, putting the total enrollment for that year at 140.

Photo: KyCAD introductory 3-D and sculptural process class.

The goal from the time the school merged with Spalding was to change its name to something that would: 1. communicate that it’s a college and not a high school or community art center; and 2. express a design component. The Kentucky College of Art + Design at Spalding University, or KyCAD, would do that. “Design was sort of a code for jobs,” Tyler says. Artist and KyCAD professor Ezra Kellerman says, “People bring their kids here and are like, ‘How are they gonna get a job?’ Well, how are you gonna get a job with a business degree? I don’t know. It doesn’t guarantee you employment.” (A Kentucky Art Council report from two years ago shows that creative jobs account for more than 100,000 jobs in the state, or 2.5 percent of the total market, and generate almost $2 billion in earnings for the state.)

“Art school” doesn’t necessarily come to mind when you see the FLAB, or fabrication lab, in what used to be a storage room. Boxes of 3-D printers, donated from GE Appliances’ design space FirstBuild, and laser cutters pile up on the concrete floor. The students will soon work on coding. “At that point you’re going into the digital realm even though it is sculpture,” professor Andrew Cozzens says. “If a student came into a (job or internship) with understanding of how to use a 3-D printer, laser cutter and basic coding, they’re extremely employable. Companies are actually starting to come out with a lot of dialogue in regards to wanting art majors, creative problem solvers. We got this donation exactly for that reason.”

The school’s BFA in studio art offers five areas of study (digital media, general fine arts, graphic design, interdisciplinary sculpture, painting/drawing) and two concentrations (pre-art therapy, illustration). (Ogden is now the chair of the department. Spalding still offers art classes separate from KyCAD to its students in other majors. KyCAD classes aren’t yet available to those students or to anyone in the public wanting to take a painting class, for example. That’s something the school is working to offer.) Contemporary art and art education is all about interdisciplinary, Smith says. “Art with business, with health. What if we connected art and the city’s obsession with sports together? I don’t know what that would look like. When students get this BFA degree, they need to be able to adapt in the environment that they’re in, which means that they’re not just in their studio making art 24/7 when they graduate. This is an opportunity to create an art school in the 21st century.”

Photo: Art by Jennifer Williams from KyCAD's 2017 senior thesis exhibition.

During the 2017 summer break, KyCAD held an event it called the Summer Soirée. The accent over that “e” pretty much describes the level of sophistication in the room. It took place at the school’s recently renovated 849 Gallery on South Third Street, in what was originally a car dealership in the 1930s. Freshly painted drywall displayed art — all kinds, including some impressive Dali-esque works — from the senior exhibition. The room of about 100 included board and committee members, dressed in summer cocktail attire, as though they were attending a Vanity Fair party. Brown-Forman beverages flowed from a chicly lit bar. In other words, people with checkbooks and pull in the art community were in attendance. Board chair and investment-management company owner Todd Lowe stood behind a podium and touted some of the school’s recent successes: a graduating class of 25, some of whom were heading to faraway schools for post-graduate studies; an incoming freshman class of 60; students accepted to prestigious out-of-state summer art programs. Owsley Brown III stepped up to the mic and announced that Davenport couldn’t make it because he was painting in Italy all summer long.

“Generally speaking, we think that this is sort of a miracle school,” Brown began with the enthusiasm of a motivational speaker. He took a few minutes to thank everyone for their support, financial and otherwise. Then he pitched P2E, or Pathway to Excellence, which is what KyCAD named its fundraising campaign that began in 2014. Out of the $8.5 million goal, they had raked in $5.5 million, he said. (After the soirée, that would reach $6 million. A year ago, Brown gave a million of his own money in honor of his late father.)

As rah-rah as the soirée was, Tyler acknowledges the height of the financial hurdle the school faces. For the 2016-2017 school year the budget was $3 million — without a lot of cost sharing for the back-office expenses that Spalding has largely covered.

If the 140 currently enrolled students all paid their tuition in-full, that would about cover expenses for the year. But the open-door mission means that most are there on financial aid, either from the government, Spalding or the art school. Tyler says that the school could break even at 600 students, a tough ask considering it has roughly the same enrollment as it did two years ago.

“We only got a couple people that are making contributions to this school,” Tyler says, “and we don’t have enough students to sustain the budget for operations. Why would anybody come here? It’s a huge risk.”

The way everyone at the school talks about Moira Scott Payne, she might as well be the deus ex machina in this story, swooping in to put the school on its proper path. At one point during the soirée, Payne, the new president and dean, stepped up, having been in town for only a few days, and talked about how excited she was to be here and how impressed she was with what the school had been able to achieve thus far. McClure stole the stage briefly to emphasize Payne’s role. “I have a reputation to be something of a risk-taker,” she said. “The riskiest thing I have ever done was shaking hands with Churchill Davenport and saying ‘yes’ to KyCAD. Churchill understands the art; Terry understands the business. Nobody understood academia.”

Spalding recently had its 10-year review with SACS. “I was really riding hard on our poor artists about, ‘No, no, I have to have syllabi. No, there have to be grades and learning outcomes,’” McClure says. “You have to prove why you gave that student a particular grade, not that you liked their work. The naiveté was so frustrating sometimes about — ‘Oh, accreditation’s just a little piece of paper.’ No, it’s not! It’s millions and millions of dollars in federal financial aid your students have now that they wouldn’t have access to. Every once in a while one of their board members will say something casual like, ‘We don’t need Spalding.’ It’s like, good luck without federal financial aid. Good luck without general studies.”

Photo: President and dean Moira Scott Payne.

Talking to the crowd at the soirée, McClure called Payne the “whole package: someone who can take KyCAD from the dream that has somehow succeeded in staying alive to something that really will pass with gravitas and grow into something the city can be very proud of.

“I was trying to explain to my husband the difference between Churchill and Moira,” McClure said, “and I said I would never give Churchill Davenport my car keys.” The room laughed. “Moira can have the car.”

Born in India and raised in Scotland (her accent could tell you that), Payne was most recently vice president of academic affairs at Cornish College of Arts in Seattle, a century-old AICAD-accredited institution. KyCAD found her through a national search firm. The fledgling art school is, for lack of a better metaphor, her blank canvas.

She and Davenport are planning to visit art schools that could model how KyCAD is structured in the future. Two of them are Kansas City Art Institute, which is its own four-year college and is not affiliated with any university, and Tyler School of Art at Temple University, which has a separate art community while facilities and general curriculum at Temple are shared. The freedom to mark itself with a specialized program gets Payne excited. She mentions a school in California that recently received a $70 million endowment from a tech company to combine art with politics. “Everybody associates artists as having active political agendas, so to actually finance a school that looks at activism and politics in art is genius,” she says. Researching what others colleges have done is something she’ll be tackling this year. “Or,” she says, “we might do something that people won’t recognize. That’s the excitement of the potential for it.”

In the meantime, the school is real-estate hungry. “We can’t afford to be producing studio after studio for them and making it only for art,” McClure says.

The students have individual studios inside the residence hall and dotted about campus, but Payne says, “We desperately, desperately need our own art spaces so we can have gorgeous facilities. I couldn’t believe it — when I came in they were painting on a carpeted floor. I thought, no!” They won’t go into detail, but Payne and Davenport have been seeking out potential campuses in other parts of town.

The first week of classes for the 2017-2018 school year, KyCAD students, faculty and staff met in the 849 Gallery for pizza and a welcome address. The place smelled like a school cafeteria — unlike on the soirée night. It was easy to spot the students, who made up the majority of the 150 or so people. Body piercings were prevalent, dyed hair and unconventional cuts the norm. Payne spoke to the group, warning them of her Scottish humor and saying that she plans to host tea gatherings. She encouraged the students to go out and take advantage of visual- and performing-art shows. “There’s a lot happening in this city and it’s one of the reasons that I came from Seattle. It’s on the up, and I think as this art college develops this city will be growing with us and we will be part of that regeneration.

Photo: Art by Edward Taylor from KyCAD's 2017 senior thesis exhibition.

“I love to tell everyone that the arts produce something like $407 billion toward the U.S. economy,” Payne continued. (It was actually $704 billion, in 2013, according to the National Endowment for the Arts.) “We are active,” Payne said. “We will have jobs and we will engage with society in ways that are meaningful and important.” Following the uplifting kickoff, another administrator stood up and bulldozed the students with things they should have on their to-do lists: remember to schedule classes on this date, and meet with advisors before this date, and the bursar is expecting tuition by this date. The crew then got on TARC buses and headed to the Speed Art Museum, where they spent the afternoon exploring.

Thanks to an aggressive recruiting initiative, most students come from outside of Louisville in other parts of the state. “The students from these small towns in Kentucky, boy they are poetic beyond belief,” Davenport says, calling it part of the “magic.” He says that a lot of high schools have healthy art departments but aren’t very sophisticated, “and maybe that’s a good thing. At MICA, the kids I’m teaching are like, ‘Are you the teacher? Tell me what you know,’ like I’m trying to impress them or something. Here, they’re just like baby birds wanting something to eat.”

Last winter a group of faculty took 19 students on a trip to New York to visit museums and soak up the culture. “Some students that come have never stepped into a museum,” Fader says.

Beginning in the ’80s, Peter Morrin was director at the Speed Museum for 20 years, and then, until recently, he led U of L’s Center for Arts and Cultural Partnerships. He says the city’s arts show signs of strength. Many leading arts organizations have experienced turnover in leadership in recent years, bringing about new energy, as the leaders — such as the Louisville Ballet director Robert Curran, Louisville Orchestra director Teddy Abrams and Fund for the Arts president and CEO Christen Boone — view their roles as beyond the institutions themselves to serve the city and state. Morrin sees the continued growth of the restaurant scene and health of galleries as signs that the city’s arts are thriving. He can’t say enough about the expanded Speed and its current staff. Amenities and activities like the skate park and the gallery hops, both of which began under Mayor Dave Armstrong’s administration, enrich the culture as well. And in Morrin’s opinion, the quality of the city’s art has improved. But he also sees negatives. For one, the city’s wealthy art collectors buy from outside Louisville. A recent blow, he says, has been the Courier-Journal letting arts critic Elizabeth Kramer go. “The cultural ecology is outwardly strong, but it’s also extremely fragile,” he says.

Though Morrin’s association with U of L might make him a little biased (and in his opinion, the work of KyCAD students has so far been inferior to that of U of L students), he says that as long as KyCAD is here, it will do good things for the city and broaden access to visual arts. “The more the merrier,” he says. “I think unless it’s endowed heavily within the next five years, I don’t know how it’s gonna survive.” He pulls out a rumpled postcard advertising a solo exhibition of a KyCAD grad at Moremen Moloney Contemporary Gallery in Butchertown. “This young man would not have a show if KyCAD didn’t exist,” he says. “He was the most impressive artist in that first show.”

Photo: Art by Shelby Thompson from KyCAD's 2017 senior thesis exhibition.

The grad’s name is Vinhay Keo. He grew up in Bowling Green after his family emigrated from Cambodia when he was 10. He knew he wanted to do something with his life that didn’t involve a 9-to-5, and he was interested in film. At first he thought about going away to a big school in California but realized the expense and competitiveness of that. Then a KyCAD recruitment officer visited his school. Keo, who was the first in his family to graduate from college, is now a KyCAD success story. He has attended two competitive summer programs: at Yale, which he says invigorated his ideas as an artist, and at the Anderson Ranch Art Center in Colorado. His interdisciplinary work incorporates photography, multi-media and installation and expresses his experience of living in two different cultures. For his senior thesis, he spent more than six months going to all the dumpsters on campus collecting shredded paper, which he used in one of the spaces he built for his show. In several photographs, Keo has painted himself white and is reclined among mounds of the paper. After seeing the show, Susan Moremen later reached out to him about creating an installation for her gallery. The opening reception was in September. Keo is now an admissions officer for KyCAD. He gets to keep a studio space on campus, which he shares with another grad who’s also an admissions counselor. He’s currently researching MFA programs he’d like to attend.

Overall, though, the city seems to be in a good position to support the school — and vice versa. Earlier this school year, the students had a show in the ArtxFM space, down the street from campus. They’ve been involved with programs at LVA. Payne, who has bonded with many of the arts leaders in town, says the school is working on a collaboration with the ballet. It helps that the 13 professors, who all have degrees and work histories from recognized art schools, are also working artists and often have their own shows and projects in town. One of the newest professors, Gwendolyn Kerber, started last year as a rotating faculty member — she would come in for six weeks and teach a course — and then got a permanent position. She’s spent her career between Berlin, Germany, and the New York area. For the past 10 years she’s been a working artist, but she says she wanted to teach again for a while and was impressed with the students, energy and vision for the school. “We’ve got a long way to go, but not in terms of the quality of the education we provide. We have first-rate faculty,” she says.

Fader's color and design 1 class is calming. The room is silent, apart from an old air-conditioning unit that hums in the corner. It’s full of natural light and overlooks a gleaming landscape across Breckenridge Street. Fader has the undivided attention of her 10 or so students, mostly freshmen. She takes a pin and tacks one student’s work, a drawing of a green walnut shell, to the wall and invites the others to critique it. None really has the vocabulary to say what they think of it or how it makes them feel. “It’s aesthetic,” one girl says. “I don’t know. I just like it.”

Fader says to the class, “There’s like this little energy in there, this little flickering because it’s made with so many different colors. And the other thing that I’m really impressed with is what’s going on around the edge in terms of the figure ground — if we squint, the edge disappears. I think it’s a feast for the eyes.”

Photo: Art by Brittney Rice from KyCAD's 2017 senior thesis exhibition.

“I’m a painter,” Fader later says to me. “The most ambitious painting I could ever imagine was building this school. It’s starting to feel more like a school rather than an experiment that was a chance.

“(Churchill and I) were talking a couple days ago — ‘Back in 2002, would you have ever imagined you’d end up in Louisville with a school like this?’” She’s 62. He’s 73. Is this where they’ve landed for good? “I don’t think a day goes by when I don’t think about that,” she says. “I’m not sure.”

Before the start of the 2017 school year, Payne set up a PechaKucha, or creative gathering, with school faculty and board members and leaders from the arts community. Each person went around and gave a presentation on who they are as people and artists, as parents and pet owners. Payne talked about herself as a painter. “Terribly nostalgic for it,” she later says in her office, which is painted blindingly white and has nothing on the walls, save for an old Kentucky School of Art logo stamped in red on the back of the door. (In early September, Payne’s belongings hadn’t yet arrived “off the lorry” from Seattle.) She mentions how, during the interview process, McClure showed her her basement workshop. “Underneath the whole of her house is this massive space with tools,” Payne says. “She’s building boats in her basement. I kid you not. It was immaculate. I was so impressed by that. I thought, wow, if the president of Spalding can do that, maybe I could get myself back into a place or a position where I might be an artist in a studio again. That’s kind of a dream.

“But not yet,” she says. “When I come in and I see the work that has to be done here, this will be my artwork for the next few years.”

This originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Cover Photo: Art by Jennifer Williams from KyCAD's 2017 senior thesis exhibition.