Where do puppies come from?

Southwest of Louisville, past the steaming towers of LG&E’s Mill Creek power plant, past the 19-foot-long fiberglass bass at Pepper Tackle, through the woods of Fort Knox and into rolling hills and cornfields, which almost look like they could be in Pennsylvania Amish country. Breckinridge County, population 20,000. Beyond the old storefronts in Hardinsburg (pop. 2,200) and the jail lies the Breckinridge County Animal Shelter. If you have a rescue dog and live in Louisville or Cincinnati (or even Kensington Palace, but we’ll get to that), there’s a good chance it came from a place just like this.

The shelter is a low white building, with a tin roof over the front door, like the porch of an old country store, only there’s no porch and no store. An old gray GMC Safari that’s decked out in pet decals sits parked out front. A round man with a Duck Dynasty beard and a hunting-camo ball cap exits the building and removes a pack of Marlboro Golds from his shirt pocket. This is Randy Miller, one of the shelter’s two full-time employees.

|

| Breckinridge County Animal Shelter technician Randy Miller holding Hazel. |

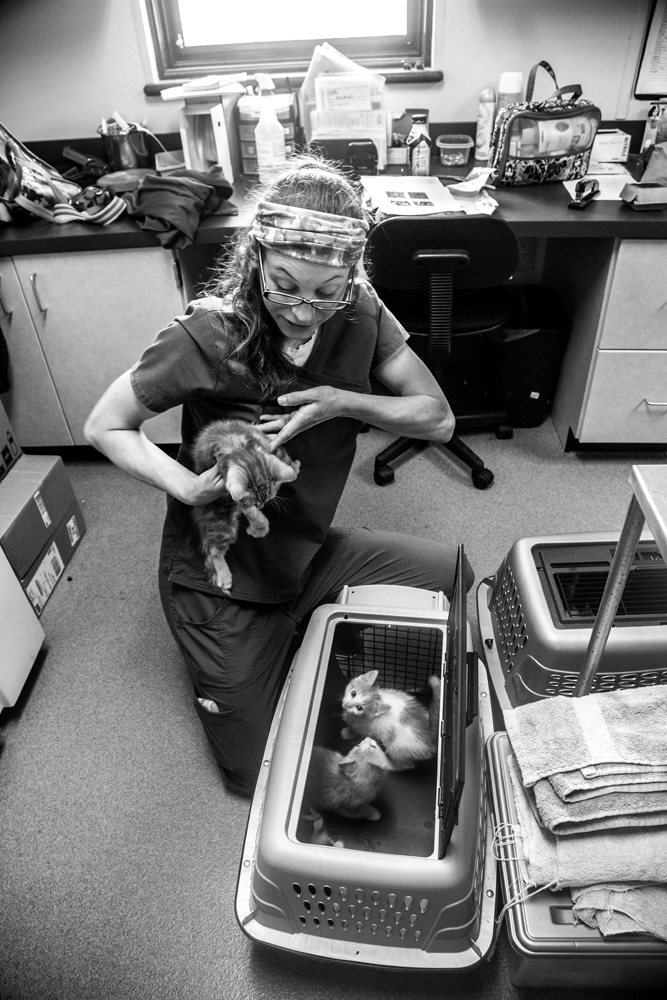

It seems empty inside until you arrive at a room at the end of the hallway that bursts with purposeful busyness. Three women are readying eight fuzzy kittens for a transport. An industrious 28-year-old with curly blond hair smiles and sticks out her hand. This is Nicole Shor, who runs the shelter. She grew up outside Chicago but went to high school here in Breckinridge County. As a kid, she had lots of pets — dogs, cats, hamsters, turtles, rabbits — before getting a zoology degree at Kentucky Wesleyan College. Today, she’s got her hands full with kittens and puppies who’ll travel by van to Louisville. The shelter does transports like this every week. Over the past four years, for example, the Breckinridge County Animal Shelter has sent 621 dogs to other places. “There are transports driving everywhere, every single day,” says Mandy Franceschina, who runs an animal-rescue nonprofit in Cincinnati called Paws and Claws, one of many groups that takes in dogs from Breckinridge County.

As it turns out, where puppies come from is a vast, complex supply chain, run largely by volunteers and a few dedicated staff in rural shelters. I wanted to see it. Because, thanks to Shor and Franceschina, I’d become part of it.

Though Shor and Franceschina have never met in person, about two years ago they were connected, as they have been many times, through a series of events that began with two unfixed dogs.

On a perfect October day in this gorgeous part of Kentucky, somebody drove to a boat ramp with two blue heeler-beagle puppies. The unknown driver was likely the owner of an un-spayed female beagle or blue heeler (officially known as an Australian cattle dog) that had a litter of puppies. Each puppy had a salt-and-pepper flecking that looks bluish from a distance, known as a “blue tick pattern,” and the tricolor markings, floppy ears and sweet face of a beagle. Brother and sister, they would have been about three months old.

The driver put the puppies on the ground near the boat ramp and drove off, actually a common occurrence in Breckinridge County. “Prime dumping ground,” Shor says, explaining that boat ramps can be out of sight. Plus, people often take their dogs on their boats, so if anyone did happen to drive by, they wouldn’t think it strange to see dogs on the ground next to a car. Breckinridge County is bounded by the Ohio River to the north and Rough River Dam State Resort Park to the south, so boat ramps are everywhere.

|

| Breckinridge County Animal Shelter technician Kala Hardin. |

Shor and her staff and volunteers have found dogs in all kinds of places — sinkholes, a storage unit, a boat. They’ve rescued dogs being shot at for straying onto the wrong property. They have found skinny dogs living in the woods, subsisting on squirrels and rabbits and whatever else they could find. They’ve found dogs that were literally mangy, suffering from a disease that makes them lose their hair and turns the skin pink, caused by unchecked mites. A recently rescued pit bull was covered in castor oil, a woefully misbegotten attempt at mange care. Once treated, the dog’s color went from rosé to champagne.

Of course, not all dogs end up in the shelter because they’re abandoned; sometimes they land there because they ran away (there’s a three-day hold to give owners a chance to claim runaways), while owners themselves sometimes surrender animals they can no longer care for.

Shor shows me around the shelter, which was founded in 2004 and has spartan, kennel-lined spaces for cats, puppies and quarantined dogs. One bowlegged bulldog has been here for nine months (old and sick dogs often have a hard time finding homes), and an Australian shepherd with behavioral issues will need to be trained before he can be adopted out. A coonhound named Luka has been here four days. He bays like a forlorn seal. Ouwww, ouwww, ouwww! “I know, we hear you, man!” Shor says. “He’s been on his own — look how skinny he is.” Hound dogs like Luka are common. “If they’re not a good hunter, people just let them go in the woods instead of turning them in,” Shor says. “Then we have to chase them, so that’s even more fun.”

The shelter only has room for 45 dogs at a time, so it must keep them moving out faster than they’re coming in. Otherwise, they’d have to euthanize for space, which the shelter hasn’t had to do since Shor arrived two and a half years ago. (The shelter does have to euthanize about 10 dogs a year in cases of severe injury or severe aggression.)

A typical dog’s stay is just two weeks. This is a way station.

It’s time to load the animals.

“Zeus and Bubbles will go right here,” Shor says. “It’s like a Tetris game trying to fit them all together.” In all, this transport is going to have 18 animals — three adult dogs, seven puppies and eight kittens.

Two volunteers from Animal Friends of Breckinridge County arrive in a gold BMW. They look like they could have just finished playing tennis in Naples, Florida. Ginny Hamm — gold hair, gold jewelry, sunglasses — introduces herself like a vaudeville comedienne: “Two of my favorite things — gin and ham.” The other, quieter volunteer is Melissa Kampars, who is one of the founders of Breckinridge County Animal Friends, which started in the early 1990s and now owns the van and runs the transports.

Everyone says “awwwww” as the shelter workers bring out two of the six Chihuahua-Jack Russell puppies. “I love it when we take loads of puppies!” Hamm says. “This is the best part of being a volunteer — puppy kisses.” The air is full of barking and howling coming from inside the shelter.

Bubbles, a two-year-old white German shepherd, pants and pulls at his leash. He sniffs at Randy Miller, then at a resident shelter cat, who gives him a good right hook to the nose. The volunteers gasp. “Bubbles! Oh!” They load Bubbles into the van before he can get smacked again.

“It’s going to be a noisy trip!” Hamm says. “Hopefully it won’t be a poopy one. For some reason, they always poop for us.”

Breckinridge County Animal Friends volunteers Ginny Hamm (left) and Melissa Kampars.

Kampars chimes in: “One time, we had — what? — four bloodhounds, and they started howling and pooping, and we were on the Gene Snyder and we had to roll down all the windows because we couldn’t breathe, and people were really giving us funny looks.”

“We were howlin’ and smellin’,” Hamm says. She gestures to the staff, which consists of Shor and Miller full-time, plus two part-time kennel technicians. “This may be the best little shelter you’ve ever been in,” Hamm says. Miller, she says, “can take the orneriest dog in the world and turn it into the right dog. He’s a whisperer. And that gun,” Hamm says, referring to the holster on Miller’s belt, “is probably full of Kool-Aid or something.”

|

Bubbles snarls at Zeus, a year-old black lab mix, who has been loaded into a crate right next to him. Grrrrrrrrrrrr.

“Now, now,” Hamm says. “We’re gonna have to separate those two.”

They find a blanket and a piece of cardboard to put between the crates.

“See what happens? You don’t get to talk to each other!” Kampars says.

More barking.

“Is it that people don’t spay and neuter enough?” I ask, trying to figure out where these dogs come from.

“They don’t,” Kampars says. “We have spay-neuter clinics in January for cats, and we’re trying to get one for dogs. And our organization sponsors a low-cost spay-neuter clinic for low-income (pet owners).” Is the main barrier the cost or the access? “I think it’s the cost,” Shor says. (In rural areas, spaying or neutering your pet can cost as much as $300.)

“But there’s an attitude among some people — they don’t want to neuter a male dog,” Hamm says.

The dogs yelp from inside the van.

“We probably need to get going,” Kampars says.

That day in fall 2016 when those two blue heeler-beagle puppies were dumped at a boat ramp, I was texting my wife Brooke pictures of adorable goldendoodles.

Partly, I blame it on Hound Dog Press, the Louisville print shop on Barret Avenue, which has a sweet basset hound named Daisy. When I went in one day, she came up and said hello, head down, tail wagging, with a face so melted it looked like a Dalí painting.

A few months later, a co-worker told me about why bulldogs have up-turned noses: “It’s so they could hold on to a bull’s nose with their teeth and the blood would drip down their faces but they could still breathe,” she said. That’s crazy, I thought. And then . . . I got pretty obsessed with dogs. How they have co-evolved with humans for at least the last 10,000 to 15,000 years. How smell is their primary sense. (They’re as hardwired for smell as humans are for vision, with 220 million olfactory receptors in their noses, compared to our five million.) How they’re all so different — all the breeds, each developed for a specific purpose over centuries of selective breeding. Dogs, like food or music, are repositories for human ingenuity, culture and genius built over generations and generations.

I wanted one.

|

| Writer Eric Burnette's dog, Tesla. |

Brooke was not convinced that we needed to add a dog to our already chaotic life of two small kids and two busy jobs. Someone in our family had been sick literally almost every week for a year and a half. Our four-year-old son was still waking us up frequently in the middle of the night. Mentally, I was hunkered down. I was caught in an endless loop of worries and chores. A dog would drag me out of the house every single day.

I sent Brooke pictures of basset hounds, both cute puppies and fat adults. Nope. “I read a story once about how a basset ate someone’s face off,” she said. Which was true — I’d sent the article to her. But most bassets don’t have sudden-rage syndrome, I reasoned. They’re sweet, docile creatures. More like cows, really. “But they can’t run,” she countered. Also true.

I tried pictures of puffy, regal Chow Chows, especially those that resemble little snowballs. Pictures of our son snuggling with my parents’ redbone coonhound-boxer mix. Pictures of Maltipoos that looked like Ewoks and goldendoodles that looked like teddy bears.

I got the kids involved, too. I took my son to the Louisville Metro Animal Services adoption center, Animal House, on Newburg Road to play with dogs. And at the park, we would play with other people’s dogs, which I discovered was a nice way to make friends with strangers.

On Nov. 14, 2016, I ran across one of the two puppies from the boat ramp on Petfinder. I emailed my wife in all caps. “LOOK. AT. THIS. BLUE HEELER/BEAGLE. I DIE.”

She grudgingly relented, writing, “OK, if you think it will help you. OK.”

I reached out to Paws and Claws Animal Rescue in Cincinnati, which had the puppy. She was still with them, in a foster home. I made arrangements to go see her and take the kids that Saturday.

It was none other than Ginny Hamm who drove those puppies to Louisville, just two weeks after they arrived at the Breckinridge County shelter in October 2016. She handed them off to a Louisville volunteer named Angela Koch, who took them up I-71 to Carrolton, Kentucky, and passed them off to Emmy Friedrichs, a restaurant manager in Cincinnati. These volunteers do this about every three weeks, sometimes more. Friedrichs then drove the puppies up to Cincinnati and was herself their first foster mom. She named them Janet and Michael. “Such adorable handfuls,” Friedrichs says in an email. Janet “was so sweet. But super hard to housebreak.” While fostering, Friedrichs said “Damn it, Janet” quite a bit. “But, man, she was so snuggly and was obsessed with Juliette” — Friedrichs’ brown pit bull. Friedrichs kept the puppies for about six weeks. Michael was adopted out, and Janet was sent to another foster mom, a woman who lives in southeastern Indiana with two pit bulls and a tiny Bichon Frise.

We pulled off the Indiana exit on I-275 and drove on some country roads until we got to a driveway that seemed to be at least 14 miles long and made mostly of hills and boulders, which was almost too much for my little Prius. (My son still asks if I remember that time the car was beeping and couldn’t get up the hill.)

I gave each of my kids treats to give to the dog, so we could make a good first impression. The woman let us inside, and there she was — an 18-pound, four-month-old blue puppy. She bounced onto the couch, which was covered in an olive-green moving blanket. “She’s…kinda crazy,” said my son, who was four at the time. (This was an accurate assessment; she still has a “Psycho Heeler” mode, when her eyes roll back and she runs around our little yard at full tilt like a maniac.) We’d also brought some toys to see if she would play. The kids rolled an orange plastic ball across the floor. She fetched it and brought it to me. And then she lay down on the couch next to me and just let me pet her for a minute. This is the one, I thought. I sent my wife a smiling selfie. The foster mom agreed to keep the pup over Thanksgiving while we got everything ready at home. In two more weeks, we would have a dog.

|

| Nicole Shor and Randy Miller loading dogs for transport. |

Less than an hour after leaving the shelter in Breckinridge County, we arrive at the Kentucky Humane Society intake facility on Steedly Drive in the South End.

Hamm opens the back door of the van. “How is everybody! Hey kitties!”

Several people from the Humane Society come out to greet the new arrivals. This is a much bigger operation than the one in Hardinsburg. There are 35 full-time and 36 part-time staff who work in the shelter and with adoptions, in addition to some 300 volunteers. The Humane Society’s spay-neuter clinic, low-cost vet clinic, dog-training classes, summer camp and pet boarding, grooming, and daycare facilities add another 30 full-time and 28 part-time workers.

“We got more little critters than you can shake a stick at!” Hamm says.

They get to work unloading the dogs and kittens.

The Kentucky Humane Society now receives these kinds of transports almost every day from any number of 35 Kentucky counties, in addition to other Southern states. They get roughly three transports a month from Breckinridge County. In a year, KHS processes about 6,500 dogs (and about 2,500 cats), and roughly 65 percent of them come from outside Jefferson County.

“We’re able to do this because spay and neuter has worked so well in Louisville,” says KHS communications director Andrea Blair.

“Ten years ago, I don’t think we would have gotten any,” from outside Jefferson County, adds Kristin Seaman, the Humane Society’s transport and rescue manager. Because the Humane Society never euthanizes animals for time or space (only for medical necessity or severe behavioral problems), they could not have taken on all these outside dogs without a reduction in local unwanted dogs. In the last 10 years, their own clinic has done 100,000 spays and neuters.

In a small room, the animals are examined and entered into the system by three staff members. There’s a list of possible names on the wall — Ketchup, Mustard, Relish, Tabasco for dogs; Purrito, Purrl, Purrcival, Luke Skywhisker for cats. “When you’re naming a few thousand animals a year, you have to get a little creative,” Seaman says. Today, it’s a Dora the Explorer theme for the puppies — Dora, Diego, Swiper and Boots. (Bubbles, Zeus and another dog, Hazel, keep their names for now.) A kitten is named after this story’s photographer, Mickie Winters. The rest of the kittens get rhyme-y names — Chucky, Jackie, Becky.

Soon, they’ll be spayed and neutered, if they haven’t been already. Then they’ll be on Petfinder and in Feeders Supply stores across Louisville. And from there, hopefully, to permanent homes.

The Kentucky Humane Society's Jennifer Allen and Hazel

Leaving the Humane Society, Hamm says, “You should play up the Meghan Markle angle.”

And here we come back to Kensington Palace, where a beagle named Guy is presumably bounding around Prince Harry’s ankles and snuggling under the favorite duvet of the new Duchess of Sussex. Guy was found in the woods in Montgomery County, east of Lexington, and from the Montgomery County Animal Shelter was placed with A Dog’s Dream rescue in Ontario. A series of transports relayed him from Kentucky to Toronto, where he was placed in a pet store. Meghan Markle saw him while she was in Toronto shooting the TV show Suits. And then, as you may have heard, she fell in love with a prince and moved to England. When she married Prince Harry at Windsor Castle earlier this year, Guy rode with Queen Elizabeth in her limousine. His new career is working out all right.

The Beagle of Sussex could have just as easily come from Breckinridge County or one of the 90 other local government shelters in Kentucky, with their steady stream of dogs heading north.

|

| Humane Society intake team member Amber Trusty. |

When it was time for my family to pick up our dog, we met Mandy Franceschina and her mother outside an Arthur Murray dance studio in east Cincinnati.

“I’m sure you do this all the time,” I said.

“We do,” she said.

Paws and Claws’ adoption process had involved some paperwork and a home visit (to make sure we weren’t running a dog-fighting ring), and a cost of $225 (but the dog had already had her shots and been spayed and micro-chipped). I signed an agreement saying I’d return the dog to Paws and Claws if it didn’t work out. (Returns happen about 9 percent of the time at the Humane Society, usually for reasons such as moving, the owner’s health or the animal not getting along with pre-existing pets.)

They got the puppy out of the car. We gave her some more treats and put her in a dog crate that we’d borrowed from a co-worker. She was totally chill the whole way home, no whining or complaining at all. When we got to the house, we gave her a Kong chew toy filled with peanut butter.

At last, not quite two months after she and her brother were picked up as strays on the boat ramp, this puppy had a home.

And within a few weeks of the transport I witnessed, Bubbles, Zeus and Hazel had been adopted too.

We re-named our dog Tesla, at my wife’s request. Mostly after the scientist and partly after a car we’ll never be able to afford. Tesla now sleeps in my son’s room. If he gets scared, he pets her and goes back to bed. He almost never wakes us up anymore.

Tesla has the body of a blue heeler (45 pounds) and the face of a beagle. Every day when we come home, she’s excited to see us — even my wife, who maintains a facade of exaggerated indifference but secretly likes Tesla more than she lets on. When Tesla gets really excited, she will run to your feet and stick her butt up in the air, wanting you to scratch her back.

It’s a bumper-sticker cliché to say your rescue dog rescued you, but for me it’s partly true. Getting a dog accomplished what I had hoped — it got me out of the house. It felt like the first break of morning after a long night, daisies pushing through the snow after months of winter. I’ve now gone on hundreds of walks I never would have taken without a dog needing to be walked. And I’ve seen marvelous things on those walks — sandhill cranes squawking high overhead; epically fiery sunsets at Highland Middle School (one of the best spots in the Highlands, I’ve discovered); kingfishers and hooting owls; and an actual double rainbow.

Dogs evolved to be our hunting buddies (which they still are for some people) and then our farmhands (which they still are for some people) and now our emotional companions. Somehow, as we keep changing, so do they.

After returning to the shelter in Breckinridge County after the transport, as I’m preparing to head back to Louisville, Shor says, “I hope you enjoy your dog.”

“Yeah,” I say, “she’s been great.”

“They’re good dogs,” she says. “It’s good to see all the hard work is worth it.”

This originally appeared in the September 2018 issue of Louisville Magazine under the headline "Homeward Bound." To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Photos by Mickie Winters, mickiewinters.com