The path leading down below the Devil’s Backbone begins like a simple question, innocuously, with a comfortable downward slope, only a slight implication of the descent to come. Thistle thorns up purple along the edge of the pavement. Wildflowers burst yellow through the grass. Occasionally the woods to the left open up onto little fields full of tall grass combed down by wind, weeds webbed in spider silk strewn with dewdrops like diamonds. A rusty barbed-wire fence along the right restrains evergreens.

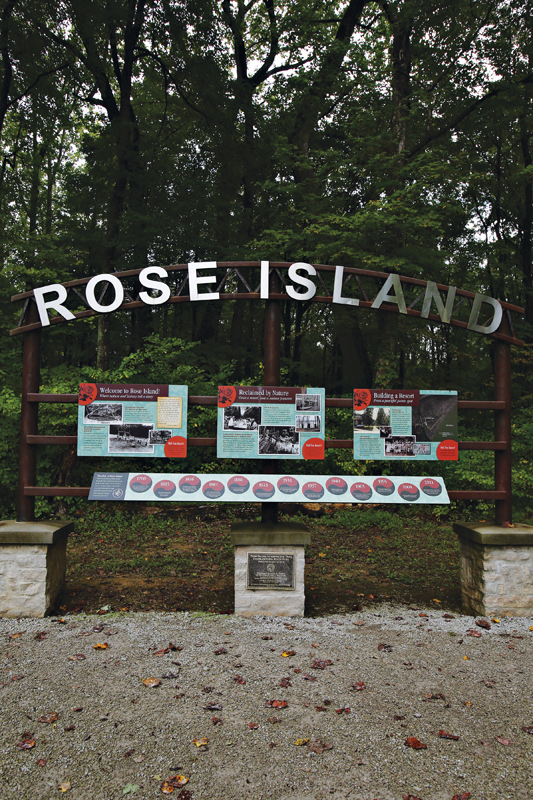

Photo: The Rose Island storyline. // Mickie Winters

The Devil’s Backbone is a high ridge, his vertebrae spiking up into a dreary sky, forested green and deciduous on this cool September day, just a few leaves predicting fall with their yellow, the Ohio River furling like a pale-green scarf down the hollow of his back. This far down trail three in Charlestown Park in southern Indiana — just far enough to lose sight of the parking lot and its squat white buildings — the question begins to answer itself: an indignant bird screeches, the path drops and weight shifts to the front of the feet. Yes, we are going down a good 70 feet, an ear-popping, blood-changing drop, down to where the woods reign. The earth drops off down the left side of the path like a hole in a tooth, ancient boulders refaced by moss. Nature has cinched up the few trees that have fallen along the walkway with vine, re-gifting them the color of life. The woods garrison on either side of the pavement, and though they can’t advance onto it, they can arrow across it — leaves reaching for leaves, veiling the sky’s white face — and perhaps even below it, roots undermining this black, human touch, unseen.

Photo: The old Rose Island entrance. // U of L Archives and Special Collections

I’ve come here today to see what remains of us when we’re gone. Down the path to Rose Island — not really an island but a peninsula along the Devil’s Backbone where 14 Mile Creek bleeds into the Ohio — I pass an old man walking a yellow Lab, a fisherman standing silent behind two rods on the bank of 14 Mile Creek and one of those vehicles that looks like a cross between a four-wheeler and a golf cart sitting empty on a rare level spot. But aside from these interlopers, this place is free of people. The woods open up, curving like half the perimeter of a ruined arena, light flooding where water once did. Before a black metal bridge with a wooden walkway stands a pole with a blue ring near the top marking the water level of the infamous 1937 Flood, which inundated Louisville and erased Rose Island, a summer getaway that bloomed here in the 1920s and ’30s. The blue ring is far higher than my 6-foot-2.

Photo: The '37 Flood marker at the bridge over 14 Mile Creek. // Mickie Winters

Here is what Rose Island had: a dance hall with a house band; 20 furnished cottages overlooking the Ohio; a restaurant with a 400-person capacity and a cafeteria with a capacity of 100; 15 Shetland ponies; a 12-room hotel; a 110-by-42-foot swimming pool rumored to have been the first filtered pool in the Midwest; a merry-go-round; a wooden rollercoaster named after the Devil’s Backbone; an unverified number of alligators and other exotic animals; a path marked with metal arches on stone columns, beginning with a stone platform in the ground imprinted with the phrase “WALKWAY OF ROSES,” which it was: Roses lined the walk, named for park proprietor David B.G. Rose. At one point, 4,000 people visited daily, dropping 50 cents for a ride over from Prospect on a steamboat ferry or walking across a wooden suspension bridge that looked like the result of Paul Bunyan developing a passion for engineering. A sign in the park says that little boys liked to scare little girls by jumping up and down on the bridge, which bounced with their weight.

Photo: Remains of the Walkway of Roses. // Mickie Winters

Here is what is left of Rose Island: three arches, rusted, and that imprinted platform; the pool, filled with gravel on which I find two red flowers and one black plastic knife, the ladders rusting away from the ground; trees so large they surely must have lived here when the park operated, carved now with initials and profanities; gravel paths to nowhere; a stone brick fountain and small moat, mossy, one side entirely collapsed; rusted metal bolts and struts of unknown origin; a squarish concrete structure, chest-high, hollowed in the middle and filled with discarded water bottles, holes in the sides leading some to believe it was some sort of water trough, though its purpose, like the cabins, the dance hall and every other Rose Island building, is lost. Poles mark where structures once stood, each indicating the level of the 1937 floodwaters that drowned this place under 10 feet in some spots, a sign at the top printed with an illustration of a plant and the word “RECLAMATION.” Not even foundations remain. Other signs are emblazoned with timelines, old ads for the park, photos of black-and-white ghosts posing on the banks of the river or perched on the pool ladders in then-risqué swimsuits, smiling — all of them white, all of them probably well-off. Along the path stand big green boxes on poles with black cranks; turn them and voices will tell of the attractions of Rose Island, grainy swing music creeping out over the grinding, plodding sound of the crank.

It is utterly terrifying.

Photo: Remains of the fountain. // Mickie Winters

Hurricane Harvey has just devastated Houston, the present flood hemorrhaging into the flood of the past in my mind. We know relatively little about this once-popular place. Even some of its ruins are a mystery. Has our technology provided so much documentation that future generations will look back on us without such gaps in knowledge? I’m not sure anyone will ever look at some heavy stone thing we’ve made with no way of knowing its original purpose. Have we transcended nature’s powers of obfuscation?

Am I kidding myself?

What ghosts want most is company. They don’t want you to leave Rose Island. You slide down the mountain to see it, and have to claw your way back up to get out. I strip to my undershirt, my heart galloping in my chest, my underused legs petrifying. Rain washes the sweat from my shoulders. And then, somehow, I’m out again. Back with the fence, the parking lot, the squat white buildings. Back in the domain of humans. The ghosts far below me in the woods, waiting.

This originally appeared in the October 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

All color photos by Mickie Winters

All black-and-white historic photos courtesy of the U of L Archives and Special Collections