Welcome to the National Physique Committee’s Kentucky Derby Festival Championship.

Photos by Joey Harrison

The music is conversation-stopping loud. Men in glittery slingshot bikinis pose onstage, arms and shoulders knotted like great challah loaves, back muscles spreading in gnarly wings from tapered waists. Backstage, Pamela Tisschy-Napier fidgets, her Texas drawl an octave higher than normal. “I forgot my badge!” she yells, referring to the round badge each competitor wears to identify herself to the judges. Someone’s making her another. In the crush around her, bikini-clad women work resistance bands, pumping muscles. Others lie flat on the floor, earbuds in, serene in the chaos. Napier, with dark eyes and dark brown hair that flows halfway down her back, is settling into her spot on the crowded floor.

She’s about to compete in the National Physique Committee’s Kentucky Derby Festival Championship, a noisy, flashy spectacle in the Galt House’s Grand Ballroom featuring 550 tight, toned and spray-tanned competitors strutting the stage to earsplitting anthems from 10 a.m. to 11 p.m. During the course of this long spring Saturday, some 4,400 spectators will pay $20 to $35 to watch the extravaganza. There will be screaming. Plenty of screaming.

Photo: Mother of six Pamela Tisschy-Napier, 47, is usually up

by 4 a.m. to put in a few hours of intense exercise.

Already the morning has been hectic for Napier. It started at 4:30, when the 47-year-old walked downstairs in her quiet Fern Creek home, all six kids still asleep. She opened the baby gate that keeps her two-year-olds, Cheyenne and Camilla, from free-ranging between floors and headed to the kitchen, past “the gated community” that was once her office. Now plastic baby fencing subdivides that room. On one side her desk sits like an exotic atoll in a tight circle of toys. On the other, there’s a bit of play space and even more toys: a riding horse, a baby trampoline, Elmo slumped and exhausted in the corner. Down the hall, four or five children’s vehicles — orange, acid-green and pink — are parallel parked, leaving just enough space for Mom to open the child-proof gate and enter the large gym that has a leg press; stacked weights on a pulley system; a contraption for abdominals, glutes, hamstrings and lower back called a Roman chair; a Smith machine, which is a self-spotting barbell frame; kettle bells; medicine balls; an elliptical machine; a treadmill; and every size weight you can think of. This may be the only grown-up space in the Napier household. The living room is a primary-color mash-up of plastic toys. The spacious back deck looks like an impound lot for the cheerfully abandoned vehicles of inebriated children.

This kid heaven is managed pandemonium, the domain of one determined woman and her husband, St. Matthews Police Department detective Eddie Napier. On any normal morning, Pamela Napier would have been up by 4 to put in a few hours of intense exercise. The week before the competition, she used the treadmill a lot and stuck to lighter weights. She had her last workout Thursday, focused on triceps, chest and shoulders, with four to six exercises for each muscle group, four sets of 10 for each exercise. Since then, she has been under coach’s orders to kick back. He doesn’t want her to take any chances while she’s at her peak. In her competitive division, too much muscle definition is a bad thing.

So this morning she slept an extra 30 minutes, then was up and running with hair, makeup and breakfast for six children with food allergies serious enough to keep EpiPens within reach. Six-year-old Brock, 5-year-old Braxton, and 3½-year-old Bradley needed uniforms for karate class with Dad. Eleven-year-old Brandon needed a ride to his Cub Scout event. And finally, Pamela needed to look smashing in a glittering string bikini that must be glued to her butt to prevent accidental slippage. Oh, yeah, and the spray tan she got the day before would need a touchup backstage.

At the Galt House, Napier and her fellow female competitors look nothing like the women bodybuilders from a few years ago: hulks with masculine shoulders and chests bulked to steroidal extremes. New, sleeker categories in both women’s and men’s competitions have driven the rising popularity and profitability of shows like the Derby Festival Championship, which is put on by Kentucky Muscle, the creation of IT professional and former competitor L. Brent Jones. This is the sixth year the bodybuilding event is part of the Derby Festival. It is one of the larger non-pro competitions nationally, Jones says, and this year it includes competitors from 12 states, although most are from Kentucky and Indiana.

Women in the festival compete in one of three classes: bikini, figure or physique. “In bikini class, they want you to look like a model with muscle,” says 29-year-old competitor/trainer Autumn Cleveland of Louisville. She turned to weightlifting in response to childhood bullying in Charlestown, Indiana, and has been competing since she was 16. In figure, she says, “There’s femininity, but like a solid athletic look.” Women’s physique features more muscularity. The category that generated the extreme body types, women’s bodybuilding, is rarely part of shows these days and isn’t in the Derby Festival. Even men’s bodybuilding isn’t the attraction it once was. “The division has shrunk,” says Jones, who’s also the creator of the even bigger Kentucky Muscle Strength & Fitness Extravaganza, which takes place in October. “When I started promoting (in 2001), 90 percent of the show was bodybuilding. They were the main event, and they went on last. Now they’re the first people to go onstage,” Jones says. “The main events are women’s figure and bikini. The increase in popularity of the sport has gone up proportionally with women’s participation.” This year 33 competitors entered men’s bodybuilding, less than a third of the 112 bikini contestants.

Jones says the evolution of bodybuilding competitions really began with the emergence of Arnold Schwarzenegger and the release of Pumping Iron, both the book and the film, which focused on Schwarzenegger’s 1975 competition for his sixth Mr. Olympia title. The film catapulted Schwarzenegger to stardom and bolstered the reputation of the International Federation of BodyBuilding and Fitness. Previously, bodybuilding had been a fractious sport, with half a dozen organizations fighting for dominance. “They would sue each other,” Jones says. “They couldn’t get anything done.” Post-Arnold, IFBB was at the top of the bodybuilding heap. Gradually, it began to make changes, creating opportunities for women competitors, and then gradually expanding categories for men.

Even as the sport expanded, the popularity of traditional bodybuilding began to contract, fueled, at least in part, by the growing awareness of steroid use, Jones says. It’s not that steroids have gone away. Louisville coach and former competitor Steve Weingarten says many competitors continue to use them, but generally at lower doses than in the 1970s. He guessed at a figure: “Say a third to half are using steroids; if you made that assumption, you’d be in pretty safe territory, although it’s probably less in the bikini category.” Steroids could create the kind of muscle striation and vascularity that aren’t favored in bikini. (The competitors in this story say they don’t use steroids.)

Jones says promoters like him have little hope of controlling steroid use. Testing, with its risk of false positives, would make him vulnerable to lawsuits, he says. Besides, today’s competition drugs are far more extensive than anabolic steroids, everything from hormone-replacement therapy in older women to various anti-aging compounds. Even drawing a line becomes difficult. Competition categories that demand less muscle bulk, as two newer men’s categories do, may be less likely to encourage steroid use.

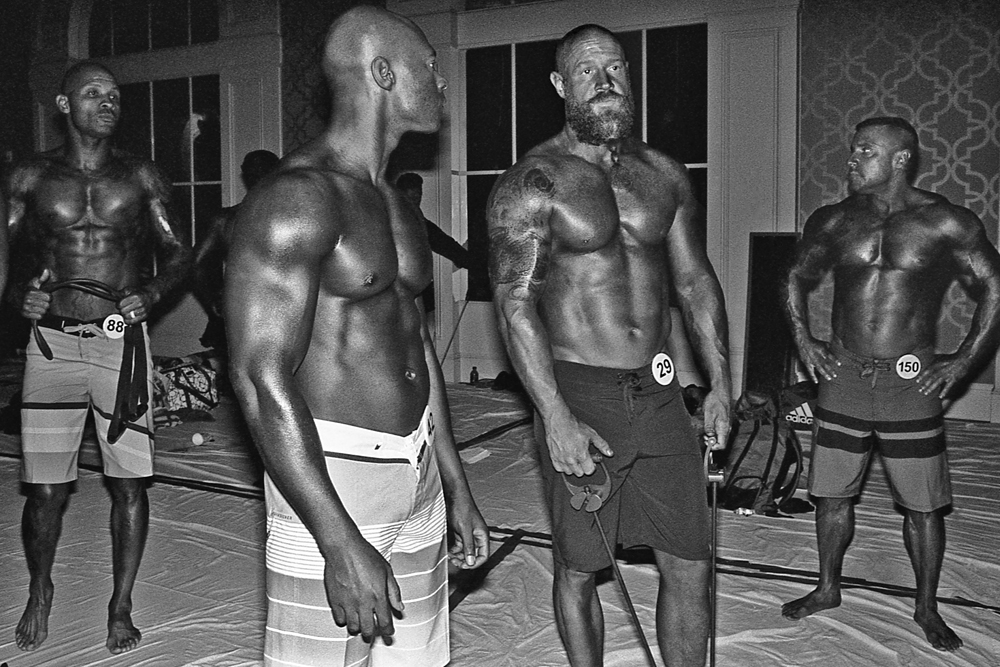

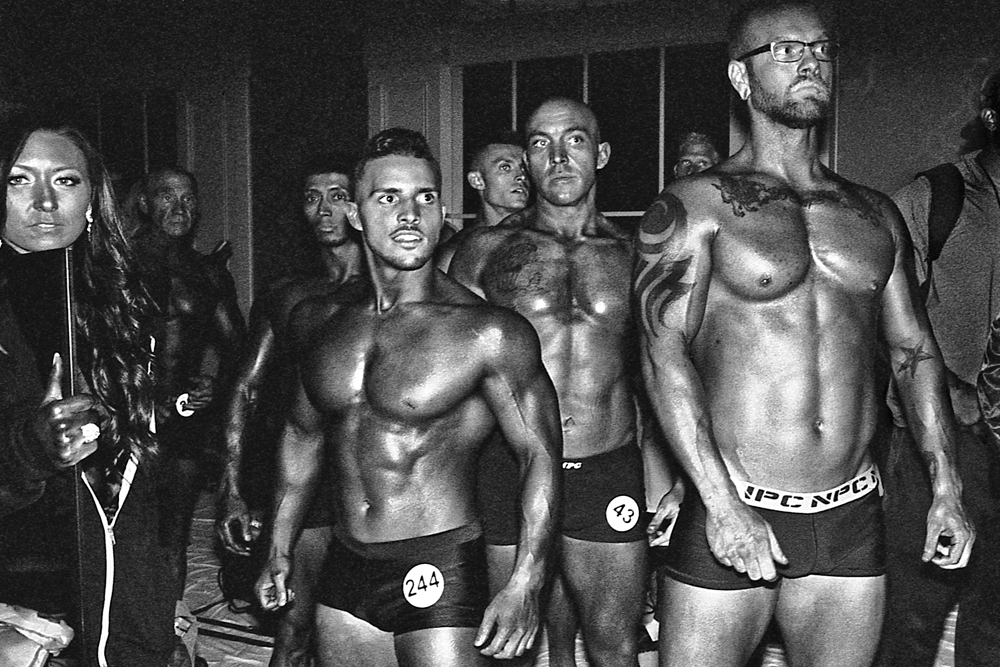

In the old days, guys like 36-year-old Myrom Kingery, of Jeffersontown, and his fellow competitors in men’s physique would have had no place onstage. Neither would the men in the classic physique category, who are more muscular than the physique group but are not allowed to exceed certain weight limitations for their height. Bodybuilders don’t have weight limits.

This is Kingery’s first competition, but he’s mellow, probably because he spends his days performing for an audience. It started a few years ago when he filled in for a friend and spent a day curling cinderblocks as an extra on the local set of a movie called Hindsight 20/20. Kingery, who worked in warehousing and logistics, turned this scant opportunity into a new career. “I love to talk,” he says. “I talked to the director and the writer for a while that day, and they brought me back a second day.” Three months later, they called him again for one of the many remakes of Hell Night. “After that, I was hooked. It was like caffeine. I had to have it.”

Photo: Myrom Kingery, 36, used to drink a 24-pack of Mountain Dew and play hours of

World of Warcraft every day. "I didn't want to be the bald fat guy with kids," he says.

He has steadily leveraged a series of small nonspeaking parts into a career that includes movies you have heard of, such as Allegiant, part of the Divergent series. “I had a scene where I killed one of the main characters. We worked on it for a week, and it didn’t even get into the film,” he says. The critics savaged the movie and audiences ignored it, but Kingery didn’t mind. “I just had a great time. I learned a lot on that film. It was my first major motion picture. I loved it.” He played a Russian soldier in The Fate of the Furious, the eighth film in the Fast & Furious franchise. His distinctive look — he’s a muscular 6’2”, bald, with a long, bushy beard — has brought steady work as a fearsome bad guy. But among the competitors at the Derby Championship, he says, he’s nothing special.

“These guys are — they’re so up there,” he says, indicating a space over his head. “I’m starting out. I’m new. I know where my place is. They’re up here; I’m down here. And I’m perfectly fine with that.…Their bodies are magnificent. I’m nowhere near that level.” For today, Kingery’s beard is ringed with rubber bands, making a skinny front-facing ponytail. As the morning rolls along, thirst and hunger are his only complaints. Like many competitors, he’s limiting liquid intake to enhance muscle definition. “Last night at 9 was my last water,” Kingery says. That was 15 hours ago.

*

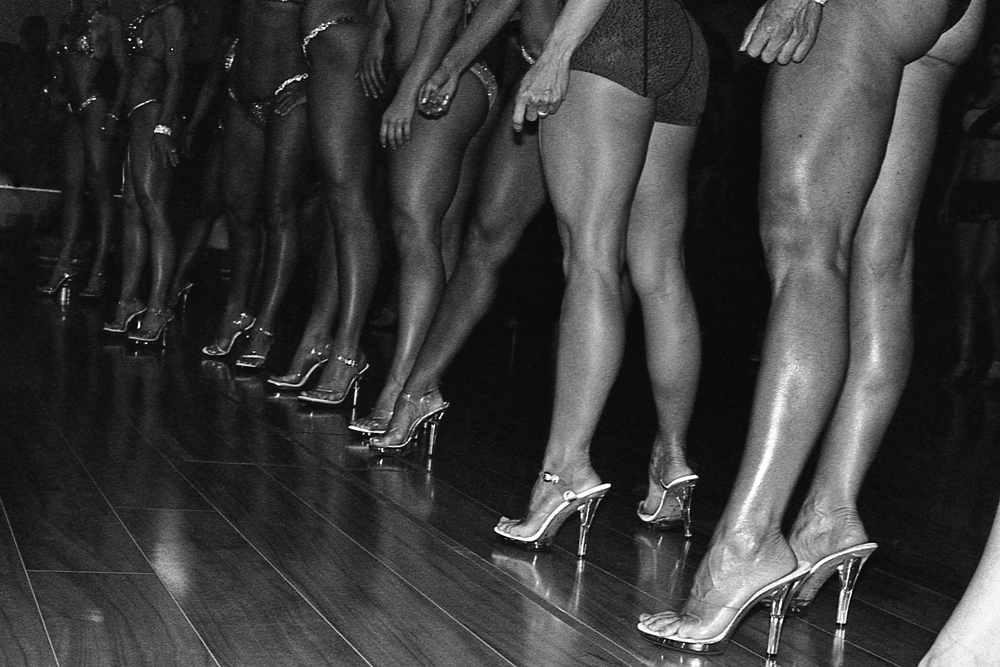

While the last of the male bodybuilders flex for the competition’s 10 official judges, bikini competitors begin to queue backstage. The bronzed group lines up shortest to tallest, the line snaking across the room. Napier, at 5’1”, will take the stage in the second group with seven other women of similar height. She isn’t pulling resistance bands like several of the other women. If she does, the veins on her arms will pop, and the striation of her muscles will stand out — both features that show on her easily, and both frowned on for bikini competitors. At 47, she’s probably the oldest competitor in her height class. None of the others in her group compete in the over-40 contest later, and only one makes an appearance in the over-35 group.

The women move onto the stage on stilettos with transparent heels. One at a time, they take center stage to pose for the judges, first facing front, then back, butt thrust out, back arched. As Napier takes her turn before the judges, the other competitors stand behind her smiling, every muscle tensed. It’s an exhausting position.

Napier attended several posing practice sessions before the competition to learn how to pull this off. Cleveland — who will win her height class in the figure competition — worked with Napier a few weeks before the contest. As Napier posed, Cleveland issued complex instructions: “Rotate the knees outward. Softly bend the knees. Push the sit bones up and back. Push your weight into the outsides of your feet. Push down through your big toe. Now drive your chest up to the ceiling. So, you’re going to have to arch your back quite a bit, almost like you’re going to do a backbend.”

“Did I talk to you about breathing?” Cleveland asked. “You know how to breathe, right?”

“No.”

Proper breathing is similarly complicated, with one objective: Breathe without showing anyone you’re breathing. And do that every moment you’re onstage.

“You have to be overly conditioned to stand like that,” Cleveland said.

Preparing for these contests is grueling business. Five to six days a week Napier spends two to two and a half hours in the gym, lifting weights. Twelve weeks before competition, when the emphasis is on losing fat to enhance muscle definition, she devotes 45 minutes daily to cardio. (“If I’m not competing, I won’t go near a treadmill. I hate it,” she says.) She eats six protein-packed meals a day, starting with nine egg whites and one egg, a half-cup of oatmeal and a few berries for breakfast. Before she began her competition diet, she was a muscular 118 pounds; now she’s down to 107, with a well-defined six-pack.

Although Napier had competed in bodybuilding competitions in her 20s, pregnancy and childbirth put an end to all that. By June 2015, she weighed 140 pounds. That’s when she entered a fitness challenge sponsored by Oxygen Magazine. Working up the nerve to send her “before” pictures almost took her out of the competition. “I didn’t want to send my pictures. I was so self-conscious about it,” she says. “Of course my husband was like, ‘You’re beautiful.’ ‘Put down that fork!’ is what he should have told me.” She lost 24 pounds in that three-month challenge, and while she didn’t win the big prize — the cover of Oxygen — she placed in the top 20. Her success inspired her to try competing again, so she contacted Weingarten and asked for a critique. “I said, ‘Pick me apart. What do I do if I want to compete?’ He told me what I needed to work on, and I just took it from there.”

*

Onstage Napier stands with her chin raised and muscles taut, while another competitor goes through her posing routine, tossing her hair and smiling over a shoulder as she pivots to arch into the back pose. Get Cool’s “Shawty Got Moves” blasts: “She move it/She move it/Her body/Her body/So sexy/So sexy/Can’t hide it/Can’t hide it.” Later, another group of women poses to the booming repeated command: “Let me see your chest,” in the V.I.C. rap “Wobble.” The bikini category can be a slippery one, far more aligned with notions of what makes a woman sexy than the other women’s competitions. The Napiers have talked about how suggestive it can sometimes seem; Pam showed Eddie a photo of the back pose. His response: “Well, the kids won’t be there.” The high heels worn by bikini and figure competitors don’t exactly scream “athlete.” “Heels make a women’s legs look better,” one trainer says. Yet women’s physique contestants compete barefoot.

“The only thing I can tell you is, it’s show business,” Jones, the promoter, says. “The role of the competitors is nonverbal communication: I should win. I have charisma. I have sex appeal. I have all these qualities I want to convey to you. I can’t talk to you, so I have to do it through my hair, my suit color.

“The sport ended the very moment you got onstage. Now it’s show business.”

Still, during a pre-competition posing workshop, some women were taken aside and coached carefully on how to do the back pose. The idea is to show off the gluteus muscles without looking like a stripper wannabe. Too much butt thrust can get a woman kicked out of the show. Somebody probably needed to tell that to the audience member shouting, “Bend a little more! A little more!” Oddly, men don’t need a similar pose to show off their glutes.

Do the sexy smiles and artfully tossed hair make a competitive difference? Weingarten doesn’t think so. “I was a judge for almost 10 years. I did not pay attention to the female face,” he says. Still, looks matter. Could an unattractive woman win one of these competitions? “No more than an unattractive man can win physique,” Weingarten says. “The look they want is what every mother would want to bring home to their daughter. But male bodybuilders can be uglier than sin and win. Male physique cannot be.”

*

No song lyrics beg men to show off secondary sexual characteristics as they take the stage. Kingery, dressed like his fellow competitors in knee-length board shorts, manages to look relaxed while he flexes. You can bet he’s hungry. In fact, he’s been hungry for the last nine weeks. Before competition prep began, he ate seven meals a day to keep up with his caloric and protein needs, including a 10-ounce steak twice daily. Now, to heighten muscle definition, he’s down to five meals daily, mostly lean proteins: six ounces of turkey or chicken three times daily, and four ounces of turkey or chicken twice a day, plus three cups of egg whites twice daily. It’s worked: He has dropped 36 pounds.

It was just the latest stage in Kingery’s dramatic long-term transformation. In 2010, as his unhappy marriage began to collapse, he weighed more than 300 pounds. “Once I got to that weight, I didn’t want to go out. I wanted to be a hermit. So I played video games,” he says. His health was bad. He was having chest pains. Every day, he downed a 24-pack of Mountain Dew. He lost himself in World of Warcraft. “I played that thing for 10 years, and I played it all day. That became my world,” he says. “My kids would go to school or daycare, and I would play anywhere from eight to 12 hours, nonstop.” He’d get home from work and play all night, getting only an hour or two of sleep. He’d play all weekend. “Looking back, it makes me sick because of all that I missed,” he said in a text.

The end of his marriage brought a major reassessment. “I didn’t want to be the bald fat guy with kids. I decided to go ahead and get things in gear,” he says. He started doing the rigorous P90X workout twice a day, every day. This 90-minute fitness program hits every part of the body, with punches, kicks, jumps, pushups, pull-ups — you name it. “I was doing it twice a day until I either passed out or threw up,” Kingery says. “What I did was not recommended.” In 45 days, he lost 30 pounds, even though he barely changed his diet. “I was like, I will just not eat so many cheeseburgers today.” But eventually, his diet also evolved.

Now, he’s fit enough to play with his kids Haley, 13; Cole, 10; and Quinn, 2. “I can do things. I can outrun them now,” he says. He wants his kids to learn to take care of themselves from his example. “That’s my big thing: teaching them. Start now.”

After Kingery finishes posing at the Derby Festival event, he heads to Jeff Ruby’s for a 10-ounce steak before stopping to nap in his room at the Galt House. Napier and her husband go to Los Aztecas on Main Street, where Pamela eats a cheese-covered steak burrito. “Then I sat in my car and chowed on chocolate,” she says. “I haven’t had chocolate in months.” In fact, she’s been hoarding it for weeks. When the Easter candy went on sale, she bought bags of the stuff. While she snacks, her husband races home to pick up another babysitter to tend to the kids. Two will watch their crew tonight.

This pack of children wasn’t part of the couple’s original plan. Eddie wanted one child, Pamela two. They compromised at six. “Brandon was such a good kid, we felt like, he needs a sibling,” Pamela says of her firstborn. But her second son, Hunter, was stillborn at 35 weeks due to an often fatal chromosomal mis-arrangement called trisomy 18. Three miscarriages followed. (She also miscarried once before Brandon was born.) Six years ago, they began fostering children. “We get kids sometimes for as little as five days. I’ve had them stay with me as long as 18 months,” she says. Then the couple adopted, first the three boys — Brock, who came to them at six months; Braxton, who arrived at 14 months; and Bradley, who they brought home from the hospital — and then, when Napier was 45 and pregnant with Cheyenne, the couple’s “miracle baby,” Camilla joined the crowd. She’s 54 days older than Cheyenne.

One day not long after the competition, she’ll take her troop to McDonald’s. The cashier will ask if she’s running a summer camp.

*

As evening falls, the competition is easier for most competitors, as judges announce height category winners and decide who among them is the best overall in his or her division and best overall for the show. Jimmy Hornback put together the 10-judge panel for the Derby Festival show. He’s qualified to judge state competitions like this one, as well as national and professional shows. Six-foot-three and 320 pounds, Hornback has been part of bodybuilding for 25 years, although he has not competed in a while. “Some people love it. There will be girls and guys who do every single show. They love competing. I never had that. I’d just as soon go to the gym, work out real hard, go home and eat pizza,” Hornback says. But he remains devoted to the sport, serving as a competition judge for the last dozen years.

Although 10 judges are assigned to the show, only seven are judging at any given time. The three extra judges allow others to take breaks during a day of demanding concentration. Every time a group walks onstage, each judge ranks the competitors from one to 15. If there are five women onstage, each judge ranks contestants as places one through five; if there are 20 competitors, judges pick places one to 15, with everyone at the tail end in 15th place. The scores are based on muscularity (that is, muscle mass), conditioning (taking leanness into account) and structure (more to do with genetics than how hard you work). An example of the latter: Some people have a thick waist or big shoulders, and no amount of exercise is going to change that. Individual judge scores are averaged to determine rankings before the evening show. In the evening, judges compare winners in each height or weight class to identify the overall winner in each category. So for top competitors, the evening event matters. “If you have even a remote chance of winning your class, you don’t want to go out and eat something ridiculous,” Hornback says.

Like chocolate.

Napier gives a little jump when the judges announce her name as a winner in the bikini open division. “I was like, ‘What?!’ I really didn’t expect that. I did not expect that whatsoever!” She takes fifth place in her height class, which means, like other winners, she’ll take home a large metal sword. Moments later she places fourth in the over-40 division for her height, which means another sword that will be displayed well out of the reach of children.

Kingery doesn’t place. And he doesn’t mind. “Even if I never do another competition, I will stay fit and I will stay active. My life will be as if I’m training to compete,” he says. “I’m never going to allow myself to turn back into the guy I used to be.”

Still, he does take a little rest.

“The day after I went out and ate a very large pizza. I ate a whole bunch of doughnuts. That was about it as far as bad food. I can’t get out of shape, but for about five days, I took it easy and didn’t go to the gym.”

Two weeks after the competition, he is on his way to Australia to meet with a producer to talk about a role in Aquaman. Then to Las Vegas, to talk to more people about even more roles, including one in which he wouldn’t be a bad guy. “I’ve got a short film coming up about a guy who lost his wife,” Kingery says.

“We’re going to see me cry,” he says. “I’m looking forward to that.”

This originally appeared in the August 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find your very own copy of Louisville Magazine, click here.