For years, when Raj Patel walked into the Swaminarayan Temple in Buechel, his spiritual home since moving to Louisville in 2015, he saw his lord looking back at him. Behind a set of glass double doors, tacked up high to a bulletin board, a full-length image of the Bhagwan Swaminarayan stared down at all who entered the red brick building, an immediate sign that this old church had found a new life and a new religion.

In January 2019, when Patel was one of the first members to arrive at the temple after somebody broke in and vandalized it, the image of his God, black spray paint covering his eyes, was the first thing he saw. “That’s when my heart just dropped,” Patel says nearly a year later.

He had a vague idea of what to expect at the temple that night. He knew a handyman had found broken windows and graffiti earlier in the day. He knew the hulking temple leader who told him about the damage had a trembling voice when they spoke on the phone. He knew the members of the temple, many elderly and foreign-born, would be shattered when they heard the news.

Raj Patel holds a defaced poster from the Swaminarayan Temple.

What he didn’t know is that the Hindu temple, with about 100 members who gather to worship, eat and socialize once a week, would soon make headlines. First, for the break-in itself. Then, for the overwhelming community response that saw political leaders and Louisvillians show up to restore a sense of safety for a group of people who had felt at home in Louisville, until they didn’t.

But before the headlines, before a surprise visit from Gov. Matt Bevin, and before Patel was pressed into service as an emergency spokesman quoted by the local news, CNN and outlets in India, a decision had to be made about the poster. “We kept it up,” Patel says. As members came to survey the damage themselves and clean up, they were met with the vandalized image. “We wanted them to see it before we removed it — not to put fear in them, but to show them what really happened,” Patel says.

|

What really happened, police say, is that a 17-year-old broke into the temple at some point between services on Sunday and the following Tuesday. He spent an unknown amount of time inside covering the walls with pro-Christian and anti-immigrant missives, some more hurtful than others. “Jesus is the only true lord,” painted on a stairwell wall, didn’t much bother Patel, who noted that the temple still has its crosses from its days as a church. “Foreign bitches,” scrawled across a bulletin board inside a children’s Sunday-school classroom, cut a bit deeper. Many of the older members of the temple are immigrants. They felt targeted and feared their children would too.

“To this day, my dad has never said anything to me about it,” says Chandani Patel, an 18-year-old freshman at the University of Louisville. She learned about the vandalism from the news after hearing whispers around her house. Her first reaction was shock, then fear, then determination to wring something positive out of the incident.

She’d get her opportunity days later at an event called “Paint the Hate Away,” which Suhas Kulkarni helped organize. A temple member and former head of the Mayor’s Office of Globalization, Kulkarni moved to Louisville in 1986, when there weren’t enough Indians here to fill, as he says, “the basement of somebody’s home.” Now, Kulkarni estimates that the number of Indian families in Louisville is close to 10,000. He wanted each to know that they are loved.

|

| Though they've been painted over, hateful messages are still faintly visible. |

On the following Saturday, less than a week after one misguided teen made an entire community feel angry, frightened and alone, hundreds, maybe thousands, helped undo his deeds. “Paint Away the Hate” drew far more people to the temple than were needed to sweep up glass or scrub away graffiti. Many just stood, their simple presence a sign of support. “That moment was the first time we realized there’s a greater community around here that showed us their love and compassion,” Patel says.

The defaced poster of the Swaminarayan, still hanging as temple members and supporters from across the city arrived to help clean up the vandalism, was taken down and replaced by hundreds of paper hearts signed by the volunteers, of various religions. And members began to let go of their anger. “Our guru, who is the equivalent of the Catholic pope, called and said to pardon him, pray that he finds the right direction,” Patel says of the person who was charged with burglary and criminal mischief. (An LMPD spokesperson would not comment on how the case was resolved because the suspect was underage at the time.) “Whoever this individual is, hopefully he learned that he made a mistake and let him go from there,” Patel says.

On a cold Sunday in mid-December, the temple appeared to have moved well past the break-in as adult worshippers sat around an ornate shrine and kids bounded down the red-carpeted hallways.

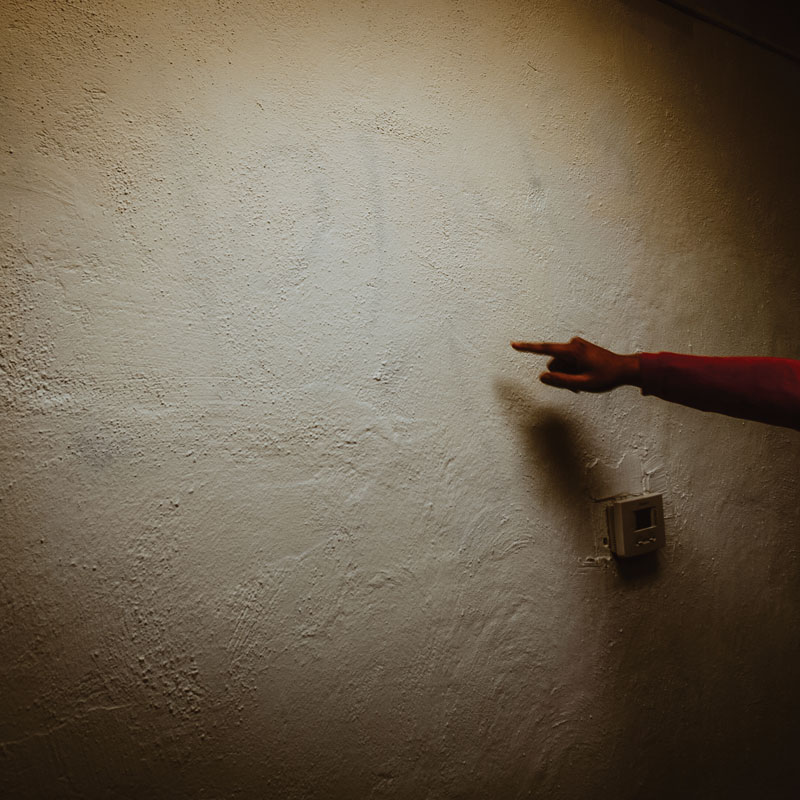

It was nearly a year later, and the temple displayed no direct evidence of the vandalism. The damage to the building had long been repaired, and the paper hearts, which stayed up for months after the break-in, were gone. The fear that had some suggesting hiring armed guards has subsided, but a security system has been installed.

If anything, Patel says, the vandalism led the temple community to feel less isolated than it once did. Members are now more aware of discrimination and more attuned to political discussions that affect them. Last March, nearly two dozen members attended a downtown vigil honoring the victims of the New Zealand mosque attack that killed 51. Prior to the vandalism, Patel says, he might have been the only one there. “It’s unfortunate that it took such a negative thing,” he says, “but I think a lot of us are better people and have more appreciation to all faiths and religions because of it.”

This originally appeared in the February 2020 issue of Louisville Magazine under the headline “Enlightened.” To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Photos by Mickie Winters, mickiewinters.com