By Mark R. Long

On a sunny and humid September morning, shortly before 20 Male High School students in two big canoes eased out of Beargrass Creek into the Ohio River, senior Genesis Leemore pointed to a spot on the bank where she dropped her phone last year. She had been clambering over a log to retrieve a dead carp so she could dissect it and see what was in its guts, a typical exercise in ecology teacher Angela Page’s “creek class.” “I wasn’t all that worried about (the phone),” Leemore says. “I was like, ‘I want this fish!’”

She and other students visit and paddle on Beargrass Creek several times a month to take samples, document wildlife and find inspiration to clean up the litter-strewn waterway. On that hot September day, Leemore sat in the stern of a 30- foot canoe near me, as I had been pressed into steering by the spiritual godfather of the creek class: David Wicks. A “retired” environmental educator who has been leading boatloads of students on Beargrass for 40 years, Wicks skippered the other fiberglass boat that morning, clad in his usual quick-dry cargo khakis and T-shirt, a tan sun hat cinched above Arthur Ashe-style wire glasses. Wicks interrogated, cajoled and needled the teens as they compared their findings on water conductivity, pH levels, temperature and other measures. “Three times a week, this is my fun,” Wicks tells me. “I failed at retirement.”

Photo by John Nation

It has been a decade since Wicks left his official role coordinating environmental education for Jefferson County Public Schools, where he spent 30 years helping kids discover the natural world and their own capacities in boats and classrooms, as well as at camps and retreats at Blackacre State Nature Preserve and at Otter Creek Park, southwest of Louisville. But the 67-year-old never stopped helping science teachers guide canoeloads of students up local waterways, never stopped working to conserve natural areas and never stopped agitating for clean water and other causes on boards and committees — and in sometimes strident letters to the editor. One example: “Sure, move here to Louisville, a river city that does not maintain its flood walls. We don’t believe the Ohio will ever flood again, and if it does, we have an ARK right upstream on the Ohio from us that would save the day,” Wicks wrote in a 2016 letter in the Courier-Journal, responding to lawmakers’ votes against MSD raising rates.

Of Wicks, Mayor Greg Fischer says: “He’s the conscience of the community as it relates to clean water, and he’s not afraid at all to apply, I would say, appropriate amounts of pressure or daylight to situations that are not moving as quickly as they should.”

Years of behind-the-scenes work and prodding from Wicks and a host of others were rewarded in August, when MSD and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers announced a $3-million study to see what it would take to restore the whole Beargrass Creek ecosystem. In September, Wicks and his partners cleared a big, early hurdle in his latest and widest- ranging effort so far: the establishment of a nationally designated water trail and guide for the Ohio River, a job that essentially calls for rebranding one of the world’s most industrialized waterways.

Creating the watery equivalent of the Appalachian Trail would scratch several of Wicks’ itches as an educator and activist: to ease the safe enjoyment of the water, to spark curiosity and a love of learning about the natural and human forces at work on the river, to inspire efforts to further clean up the sprawling watershed and to breathe new economic life into towns languishing on the river’s banks. Trying to sell the river as a recreation destination may seem quixotic. Allergy-plagued Ohio Valley residents have gotten used to seeing the waterway — when they consider it at all — mainly as a grody conduit for bargeloads of coal, chemicals and grain. When the river makes the news, it’s often because a boater died, floods threaten, poisons were spilled, barges crashed or toxic algae is blooming.

But the sights on a nine-day, 250-mile voyageur-canoe trip in June revealed why Wicks and his allies in Louisville, Cincinnati and other towns are so charmed by the heavily engineered Ohio: Bald eagles scanned their domains from riverside branches; bosky knobs emerged as the early sun burned through the fog; herons stood poised to stab the shallows for a meal; a retired brick power station glowed pastel in the twilight. “What I tried to communicate with the children that I worked with over the years is the ‘three C’s’: calm, cool and collected,” Wicks says. “Our life is too hectic, and river time restores that sense of being calm, cool and collected, so you can appreciate the natural beauty.”

This beauty, complemented by the pulled-pork-rich hospitality of officials in a string of riverside towns, was relished by crews of Chaco-sandal-shod paddlers recruited by Wicks and his partners to serve as ambassadors and barkers for the first phase of the Ohio River Recreation Trail. One canoeload of paddlers, including me, sweated the first leg from Portsmouth, Ohio, to Cincinnati, where two more voyageur canoes joined to make a grand arrival into Louisville four days later.

Wicks explores Harrods Creek several times a week. // Photo by Joe Wolek

It wasn’t the first eccentric entrance to Louisville for Wicks, who was born in New York and raised in northern New Jersey. One oft-repeated myth about the man should be put to rest, however: He didn’t ride a bicycle more than 700 miles from New York to Louisville in 1979 for the interview that landed him his first job with Jefferson County Public Schools. “David flew to Louisville and had to ride his bicycle in the pouring rain from the airport to the interview,” says his equally adventurous wife, Fife Wicks. “Then he bicycled back to New York.”

The irregular introduction to a sodden Wicks was a plus for Stu Sampson, then an avid cyclist who was in charge of student assignments and transfers for JCPS. He needed an expert for an Outward Bound program to reform troubled students. “He was a true outdoorsman, with an education,” says Sampson, who hired Wicks and mentored him as he learned to navigate the school system and growing responsibilities.

Wicks by then had chalked up a long list of adventures. He’d paddled several times around Hudson Bay and Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula, climbed mountains in Colombia, thumbed rides and bicycled all over the U.S. He’d sold Army-surplus boots in California, packed tuberoses for leis in Hawaii, helped on Polynesian archaeological sites and led outdoor adventures for city kids. After a footloose few years, he returned to New Jersey to finish college at Rutgers University, where he got a bachelor’s degree in international environmental studies and met Fife. On their first date, the pair went down the shore near the coastal town of Toms River to go paddling, even though it was March, and even though she’d never been in a kayak before. Shortly after launching off the beach, four-to-five foot waves swamped the boat. “She had a better dry suit on and she swims to the shore,” Wicks says. “I finally wash up on shore half-conscious, and the ambulance takes us both over to the hospital. And so then, she decides that I’m the person for her — we started dating and we’ve stayed together forevermore.”

In 1979 Wicks, who was teaching seventh-grade science, got his master’s in education at Fordham University. He and Fife made a deal: Wherever one of them got a job first, that’s where they’d go. When they got word from Sampson to come down to Louisville, they loaded down Fife’s tiny two-stroke-engine Honda with all their belongings and headed south.

Soon after arriving in Louisville in 1979, the couple lived in a powerless, waterless apartment above a Bardstown Road warehouse that would later become Ramsi’s Cafe on the World. But Wicks spent as many as 150 nights outside at Red River Gorge, where he tried to force-march the delinquency out of troubled teens.

This work to reform troubled high school students was the core of that first job here, running a program called Project Innovative Diversion. An offshoot of the Colorado Outward Bound program, Project I.D. garnered federal funding as the school board worked to iron out the difficulties of merging the city and county school systems, and the start of busing a few years earlier. “Some people just don’t realize…what a difference having these kids outdoors makes when they’re working on their own self-perception and their ability to interact with other people, whether they’re adults or just other kids,” Sampson says. “It takes a special person to know how to integrate that into their whole life’s perception.” (Project I.D. evolved into a broader environmental-education platform serving thousands of Jefferson County school kids.)

Wicks’ base of operations — and home for 20 years — soon moved to the Blackacre State Nature Preserve near Jeffersontown, which had been donated to the state by the late Judge Macauley Smith and his wife Emilie in ’79. There, as many as 10,000 elementary and middle-school students a year participated in programs acquainting them with the history, folkways, plants and animals of the 200-year-old farmstead. “(Wicks) believes in order for people to understand, you have to be in the environment,” says Nancy Stearns Theiss, a former environmental-education coordinator for the state who introduced Wicks to Judge Smith.

A couple thousand JCPS teachers a year did professional-development sessions at Blackacre, learning how to incorporate lessons from the outdoors into their classes. These sessions also took place at Otter Creek Park, where Wicks for several years in the ’80s and ’90s ran camps for kids to get outdoors for a few days and nights. Fife was never far, working as registrar at Camp Piomingo at Otter Creek and as a steward and farmer at Blackacre, where the pair raised their three adopted children.

|

Wicks in 1984 floating on the Ohio in the first of several boats he has built, this one made in 1976. "I have taken it down so many rivers," he says. |

In the early ’90s, Wicks earned a doctorate in educational program development at the University of Louisville and became co-director of its Kentucky Institute for the Environment and Sustainable Development. (Last year, that program became the Envirome Institute.) The doctoral program led to yet another additional job, instructing aspiring teachers at U of L. Meanwhile, Wicks also helped Gordon Garner, then the head of MSD, and others to form the first Beargrass Creek Task Force, an early effort to clean up the watershed. “He would get up at 4 every morning,” Fife says. “We’d have friends over for dinner, and suddenly David would stand up and say: ‘I’ve got to go to bed now.’” In the early 2000s, the couple had left Blackacre and moved into the first house of their own, in Prospect overlooking Harrods Creek and a shed full of canoes and kayaks, several of which Wicks built himself.

Over the years, public educators across the state and nation faced tightening standards that compelled them to focus on instilling isolated reading, writing and math skills. Students and teachers got fewer hours for less-structured experiences outdoors, Wicks and others say. “Sometimes I think that academic focus is a good thing, but it’s to the exclusion of everything else,” Wicks says. Kids still visited Blackacre but got less time to wander and make their own discoveries. Fewer campers made it to Otter Creek.

JCPS maintains that students get ample opportunities for outdoor exploration, only now it’s in the hands of individual schools. “We’re still offering the same experiences that we were in the ’80s and ’90s, they just look different because our education world has changed,” JCPS spokesperson Toni Konz Tatman says. She says the district doesn’t have a full-time staffer at Blackacre as it did for decades, but students still take field trips there. JCPS for the past few years has been decentralizing much of its operations, funneling scarce funds to individual schools, some of which have an environmental focus, says Suzanne Wright, JCPS director of academic project management. “The money needs to be in schools; that’s where the kids are,” Wright says.

In the early 2000s, Wicks’ focus shifted toward making the school system itself more environmentally friendly. He helped found the Partnership for a Green City, which brought together JCPS, Metro government and U of L (and later Jefferson Community & Technical College) to find ways to cut energy waste and better manage land and water use.

His taste for travel was whetted anew in these years by trips to China, South America and elsewhere for programs he joined as a board member and as president of the North American Association for Environmental Education. By 2009, amid broader shifts in education, a chance to teach a program in Taiwan and the lure of other projects, a retirement backed by JCPS benefits was too tempting to pass up. “If I retired now, would I have the same energy?” Wicks says. “I retired at the time I was feeling good.”

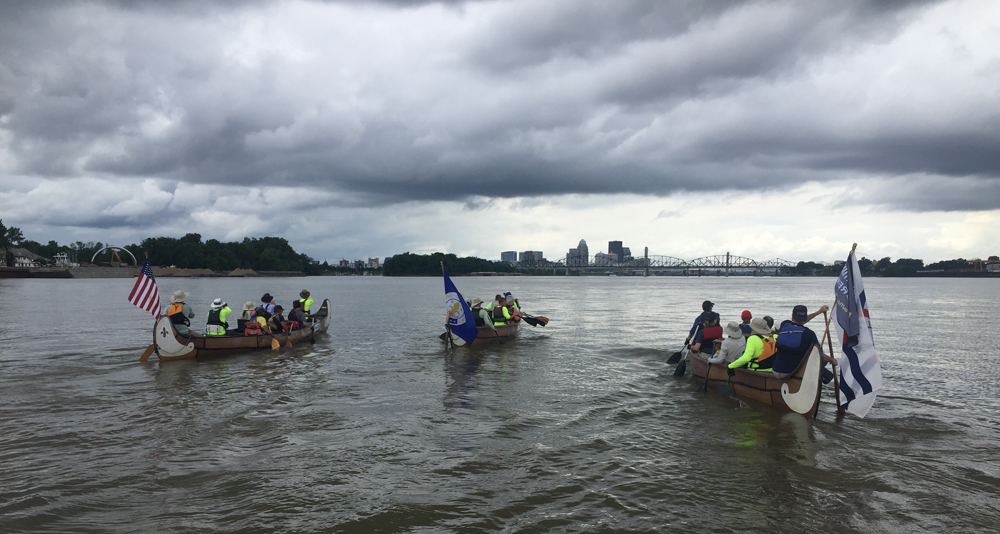

Paddlers make their final approach to Louisville in June. // Photo by John Nation

Wicks says he skipped the Taiwan opportunity to help Fife, who kept working as a teacher after being diagnosed with cancer shortly after her husband’s retirement. In the following years, he kept teaching classes at U of L, started River City Paddlesports, produced a documentary about Beargrass Creek and pressed for clean water and conservation on various boards. He paddles three or four times a week on Harrods Creek, often making his way onto the Ohio. And every spring he competes in the roughly 300-mile-long Everglades Challenge — a Florida small-boat race for the nuttiest of paddlers.

Percolating in his mind all the while has been the idea of getting an official water trail established for the Ohio River.

Fast-forward to about 6 a.m. on a Saturday in June, at Louisville’s community boathouse — another product of persistence from Wicks and others. Instead of chattering teenagers it was a gaggle of drowsy, mostly middle-aged paddlers badgering Wicks about which car to get in, where to put a case of Fife’s (superb) homemade granola or which route would be the best to Portsmouth, Ohio, for the start of the “inaugural” recreation-trail voyage. Wicks called for attention. “Let’s make one thing clear: I am not the only one who can make decisions,” he said, a rare lie from the trip leader, who also bears the more exclusive title of Kentucky Admiral.

Ghastly forecasts most nights proved to be wrong, with sunny, just-hot-enough weather easing the labor for paddlers wending their way downriver. Vanceburg, Maysville, Augusta, Cincinnati, Aurora, Rising Sun, Vevay, Westport and finally Louisville rolled out mayors, fire chiefs, tourism directors, reporters and others keen to see how a water trail might draw tourists, dollars and attention to their towns. “I’m hoping this is the beginning of something great,” said councilwoman Joni Pugh of Vanceburg, where the town put in a new stone staircase at the waterfront for the visitors. “We’ve lost our shoe factory; we’ve lost our income,” she said, echoing concerns of others there and in towns downstream whose relevance faded with the paddle steamer, and where local manufacturing failed or moved away.

To turn the economic tide in these small towns will take a lot more than the Ohio River Recreation Trail, which itself is years away from getting a coveted spot alongside the Hudson, Great Miami, Willamette and others in the National Water Trails System. But the Ohio River effort, led by Wicks and Brewster Rhoads of Cincinnati, came a step closer when the National Parks Service in September accepted the group’s application. A lengthy development process remains, but final acceptance would literally put the Ohio water trail on the Parks Service’s map, drawing more attention and possibly broader financial and logistical support. For Wicks, the publicity from the trail effort “is a way of encouraging our elected officials to deal with our streams.”

In the meantime, he plans to continue leading trips up Beargrass Creek, where his influence is visible in the work of protégés, like creek-class instructor Page, and their students. In fact, a Male graduate who studied with Page is leading the new Beargrass study for the Army Corps of Engineers.

One current student, senior Katie Norman, was setting the pace in the bow of one of the big canoes that hot morning in September. The 17-year-old earlier recalled her first Beargrass Creek outings, seeing the floating mounds of plastic trash and hearing Wicks’ stories of how Louisvillians abused the waterway over the years. “I was just amazed that people at one time thought that that system was OK,” she said. “And then we get to the plastic island, and I was just in shock. That’s when the wheels began turning about how I could make a difference in my community.”

She spent months talking three classmates into helping her with a project to illustrate the scale of the problem: building a boat out of thousands of plastic bottles tossed out by fellow students. This spring, the team arrived at a design using duct tape to secure more than 2,500 bottles. They finished just in time to present it at a mayoral press conference and float it in a Memorial Day event at the waterfront.

Last month, Norman was gratified to see the boat unveiled in its final home: an exhibit at the Kentucky Science Center. She credits Wicks for the inspiration and the help turning a class project into an event lauded citywide. “Basically,” she says, “I’m just a soldier for David Wicks.”

This originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of Louisville Magazine under the headline “Stream Dream.” To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Cover photo by John Nation, johnnationphotography.com