By Amina Elahi

Photos by Chris Witzke

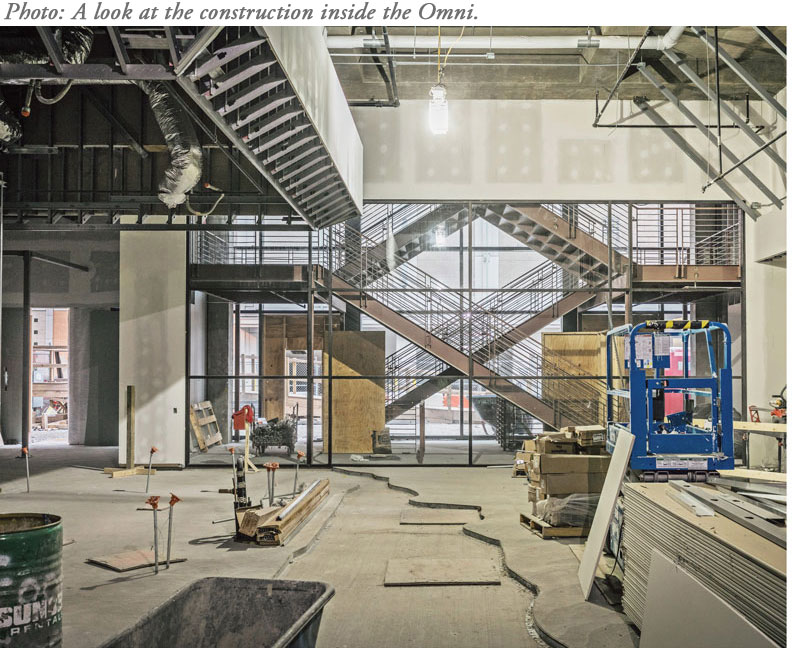

The metallic skin of the Omni Louisville Hotel has risen, a Jenga game of glass and concrete downtown. On this fall afternoon, the smooth exterior camouflages the construction workers and machinery inside. Crews in hard hats and neon vests are busy working toward a March 6, 2018, scheduled opening.

The Omni — bounded by Muhammad Ali Boulevard and Second, Third and Liberty streets — is the most visible, publicized and, at 30 stories, largest of 13 confirmed new hotel developments in the metro area, most clustered near the Central Business District, though some will pop up in St. Matthews and near the airport. The offerings range from the glitzy (the Omni; a dual-brand Moxy/Hotel Distil on Whiskey Row; and a hip AC Marriott in NuLu) to the convenient (a TownePlace Suites by Marriott in Jeffersonville). And it’s not just the new. The Marriott downtown, which opened in 2005, is in the midst of its own $32-million renovation. The Hyatt Regency on Fourth Street renovated its 393 rooms last year to the tune of $14 million. (These developments are in addition to the Hilton Garden Inn, Aloft and Embassy Suites, all of which opened downtown within the last few years.)

The reopening of the Kentucky International Convention Center downtown, slated for August 2018, is the catalyst. Its $207-million expansion and renovation — commenced in 2016 — will grow exhibit space from about 146,000 square feet to 200,000. The facility will support 1,055 full- and part-time jobs. (A spokesperson says the Omni expects to have more than 400 full-time employees.)

Photo: The new Omni towers over the once-new Marriott.

Currently, visitors to town can choose from nearly 19,000 hotel rooms, 5,000 of them downtown, according to the latest figures from the Louisville Convention and Visitors Bureau. By 2018, the CVB expects an additional 946 rooms to be available downtown. (The Omni will have 612 guest rooms and 226 apartments.) Compared with similar-sized cities, Louisville’s inventory of hotel rooms is among the smallest. It beats out Omaha and Milwaukee but offers less than half the rooms of Nashville (40,494), according to figures from commercial real estate firm CBRE. It also falls behind St. Louis, Kansas City and Indianapolis, all of which offer between 31,000 and 39,000 rooms.

Dallas-based Omni has properties flung across the continent, from Palm Springs, California, to Pittsburgh to Puerto Aventuras, Mexico. The company looks for what Omni Louisville general manager Scott Stuckey calls “emerging markets” — those that offer attractions for tourists (say, bourbon and horse racing and a respected food scene) and opportunities for business travelers, but that currently lack the appropriate supply of hotel rooms. “We obviously compete against (the other hotels) sometimes, but when we are going after a convention of 800 people or 1,000 people…we need the Marriott next door, we need the Hyatt down the street,” he says.

Among the Omni’s local touches will be: floor lamps with baseball-bat legs, carpets with a design that resembles splashes of bourbon, side tables that look like bourbon barrels. One of the rooftops will feature a pool, bar and cafe. Pin and Proof, a speakeasy/bowling alley, will have a semi-secret entrance from the back alley marked by neon signage. The Falls City Market will include barbecue, sushi and crêpe food stalls. Stuckey describes the market as “Whole Foods on steroids” and compares it to Eataly, the upscale Italian food emporium with locations in New York and Chicago.

Early on, room rates will start at $159 a night and later in the year could reach more than $399 per night, excluding high-demand periods such as Derby, an Omni spokesperson says. Stuckey says the property has already booked 115,000 room nights through 2023, including for corporate groups like Humana; SkillsUSA, an organization for educators and students; and Connect, a conference for meeting planners.

The Marriott, the only hotel attached to the convention center, is scheduled to wrap up its renovation after the convention center reopens. Marriott spokesperson Shane Weaver says the hotel has booked more than 200,000 room nights for corporate groups through 2022, outpacing previous peaks. (Rooms range from $139 per night in the off-season to the high $200s during busier times. During Derby, Weaver says rooms can go for as much as $1,399 a night.) “When you build all these new hotels, the (convention) center is really helping us maintain those occupancies so all of us don’t lose,” Weaver says. “If we built all this new supply and do not bring in more conventions, we’re all going to lose.”

Stacey Yates, vice president of marketing communications at the CVB, says the group’s sales team will now be able to pursue groups that need more space than what the old convention center offered. Capacity issues at the pre-renovation convention center drove the National FFA Convention, which had been in Louisville on and off since 1999, to move its annual agricultural-education meeting (and some 67,000 attendees) to Indianapolis starting in 2016. And Yates confirms that Louisville missed out on two conventions because a Kentucky law, signed by Gov. Matt Bevin this year, prompted California lawmakers who perceived it as homophobic to ban state-funded travel to Kentucky.

Tourism, Yates says, is on the rise, with more than 16 million visitors in 2016 compared with 11 million in 2007. The majority of travelers to Louisville — nearly 82 percent, according to a 2016 CVB study — get here by road. Yates says a factor that could hurt Louisville’s chances of attracting more business travelers is one many second-tier cities share: difficulty in getting direct flights. That could impact how successful the city will be in scoring conventions for, say, doctors, lawyers and engineers, which draw attendees from across the country. Unlike the National Farm Machinery Show, which exhibits at the massive Kentucky Fair and Exposition Center near the airport, professional associations need less space but want access to hotels and downtown attractions.

All this development, while praised by city and business leaders, does not impress Martina Kunnecke, president of the volunteer group Neighborhood Planning and Preservation Kentuckiana. “What we see is a downtown that is less responsive to local needs and more in the hands of entrepreneurs who are getting preferential treatment,” Kunnecke says. Rather than the city addressing the lack of affordable grocery shopping downtown or mixed-income housing, Kunnecke says the overall focus is instead on turning downtown into a tourist destination and offering tax incentives and waivers to developers. The Omni, for one, is paying $150 million, or 52 percent, of its development costs, with the remaining $139 million coming from the city and state through a dedicated tax-increment financing, or TIF, district, which will allow a portion of sales, property and employee income taxes to go toward repaying city bonds to fund the project. And the Omni construction hasn’t been without controversy: Preservationists protested the dismantling of the historic Louisville Water Co. building on the site, and immigrant construction workers went on strike, claiming they were making up to $20 less an hour than other workers.

George Timmering, who owns the pizza restaurant Bearno’s by the Bridge on Whiskey Row, says the convention center’s 2016 closing has hurt his sales about 10 percent. “We’ve been — myself and a lot of businesses on (Whiskey Row) — trying to be mean and lean since earlier this year. Just kind of holding on and make money when we can,” he says. “We know 2018’s going to be a special year in Louisville with the Omni opening up, the Old Forester Distillery (on Whiskey Row) and hopefully the convention center. I plan to get all of those lost sales back and then some.”

Developer Chris Anderson works for Merrillville, Indiana-based White Lodging, which owns and manages the downtown Marriott and is behind the new Whiskey Row hotel project, where road construction started in late October. Whiskey Row will have new-from-the-ground-up guts behind preserved facades. The menus of its currently nameless restaurant and two rooftop bars will feature items including bourbon-inspired mac and cheese, burgers and porterhouse steaks. Guests will also have access to in-room record players and private pool decks. Anderson is confident about business- and leisure-travel trends but says he might worry if other cities cleaned up and started competing for the same groups.

Mark Eble, a Chicago-based managing director at CBRE who has analyzed Louisville since 2004, says efforts to recruit more convention business aren’t unique to Louisville. “All of the cities are competing with one another. They keep an eye on each other and (might say), ‘Well, geez, Louisville did this fantastic thing with their convention center, maybe we ought to do something,’” Eble says. “It’s a highly competitive environment for conventions.”

Competition will also be tense between new hotels and older hotels, whose history and charm may not entirely make up for small bathrooms and creaky floors. “There will be winners and losers,” Eble says. “I’ve been doing this for 30-plus years, and if I’ve learned one thing: Generally speaking, new almost always beats old.”

Tell that to the Galt House, a 1,300-room, two-tower hotel on the riverfront that opened in its current form in 1972. It announced plans earlier this year for a major renovation that will touch all its guest rooms, meeting spaces and public spaces. David DiSalvo, the property’s director of sales and marketing, did not share cost details but says it will be the hotel’s most ambitious yet. He says he does not view the new hotels as a threat. “As a hotel, we’re renovating to stay relevant. I think the city is expanding the convention center to stay relevant,” DiSalvo says. “You always have to look at how you can improve your destination.”

Photo: Even the Omni's carpeting picks up on the bourbon theme.

Developer Robert Habeeb’s firm First Hospitality Group, based in Rosemont, Ill., opened a 100-room Home2Suites in the NuLu neighborhood in October. Habeeb says neighborhoods outside downtown will also become more attractive for new hotels because they’ll be able to offer proximity to restaurants and bars. But he admits there is some concern that developers could be overzealous and end up flooding the market, particularly in the Central Business District, which he says is at risk of adding more rooms than demand necessitates. (An Insider Louisville story in November detailed the bankruptcy filing of Le Centre on Fourth, which owns the Embassy Suites that opened in 2015 across from the historic Seelbach on Fourth Street.)

Habeeb hopes hoteliers will ease up before another recession or global event causes a market correction. “At some point, the numbers will show that enough is built. It’s like drinking and a hangover,” Habeeb says. “Unfortunately in our business, it’s the hangover that wakes people up.”

This originally appeared in the December 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.