By Jenny Kiefer

Photos by Mickie Winters

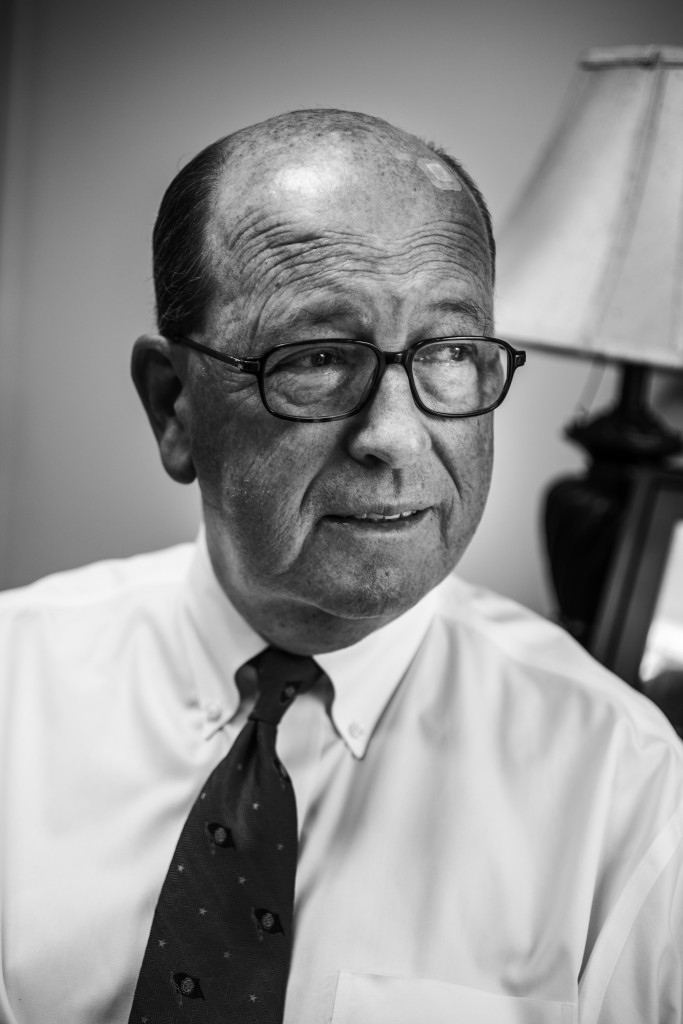

The patient: Nat Maysey, 18 (pictured above)

The surgery: arm replantation

In Nat Maysey’s room at University Hospital, only slivers of blue are visible behind the get-well cards — some colorful with cartoons, some inspirational with rolling script, some handmade from construction paper — and a purple Louisville City soccer jersey hiding the walls. A stiff, white brace encases his left arm, which he lifts occasionally. Maysey’s mother, Alisa, sits at his bedside.

“I would say there are probably about 115 (cards) now,” she says. “I haven’t counted. Probably 20 of them are from people we don’t know.”

It’s been just over a month since doctors reattached her son’s arm.

There’s a spinning machine inside the manufacturing plant in Glasgow, Kentucky — components inside rotate clockwise, counterclockwise. There are pieces — Alisa, who’s more talkative than her son, calls them “baskets” — Maysey manually manipulated as a temporary employee at work. On the morning of June 6 — 12 days after graduating high school, just his sixth day on the job — Maysey reached in to complete his task and got caught. The machine’s gears closed around his fingers, twisted against his arm, pulled him in. “I just leaned back,” Maysey says. He felt relief only when his arm detached a few inches above the elbow. Better his arm than his whole body. He felt no pain — or can’t remember feeling any — until after the surgery.

Other workers reported Maysey running from the site of the accident, yelling for help, but he has no memory of this. A volunteer firefighter yelled for a belt. Another worker handed the firefighter his two-inch-wide leather belt, which the firefighter tightened around the top of Maysey’s wound. (The doctors would later call it a perfect tourniquet.) Maysey felt a slight sting — the only discomfort he recalls — and the bleeding ceased almost immediately. Other co-workers piled ice into a barrel while another extracted the 18-year-old's arm from the machine.

“From what we’re told, everything that happened after the accident, the people responding did everything right to make his replant possible,” Alisa says. This includes calling for a helicopter to fly to Louisville instead of rushing to a local hospital less equipped to handle such a severe injury. “My arm probably wouldn’t have made it otherwise,” Maysey says.

Wide awake after the accident, he called his mother while waiting for an ambulance outside of the plant. “Mom, you need to come here,” he said. “I’ve cut my arm half off.”

“I just thought we were going to make a trip to the ER for stitches,” Alisa says, thinking exaggeration, maybe a bad cut. Thinking: Mom can fix it with a bandage. But she arrived to fire trucks, police cars, ambulances. She was so frantic that an EMT blocked her path, telling her, “Ma’am, there’s a lot of blood.” She needed to be calm. “When I walked in and saw that there wasn’t an arm hanging there,” she says, “I just thought about how his life was changed forever.”

In the minutes before a helicopter landed on the scene, Alisa sat with Maysey as he was given preliminary treatment in the back of an ambulance. She rubbed her fingers against his forehead, the constant motion calming. As they prayed together, Maysey said, “Mom, I don’t want to die.”

“You’re not going to die,” Alisa said. “They’ve stopped the bleeding. You might lose your arm, but you’re not going to die.”

Suddenly, panicked: “I’m sweating, Mom! I’m sweating!”

“We’re all sweating,” his mother said. “It’s hot in here.”

Later, she asked him: “Did you think profuse sweating came right before death?”

And he said, “Yeah, I kind of did.”

Maysey was lucky to be in Glasgow, only a 40-minute helicopter ride from University Hospital. The Kleinert and Kutz Hand Care Center hosts the world’s largest fellowship for hand and microsurgery. In 1999, its surgeons performed the first successful hand transplant in the nation. Dr. Elkin Galvis, the lead surgeon on Maysey’s case, says there’s a time limit for reattachment: “After six hours, you can’t try to replant because the muscles start dying.” The team had to reject a potential patient from Georgia, an 18-year-old who lost a limb in a mining accident. The timing was wrong, unfortunate; he’d already spent three hours in a local hospital. There was too little time left to transport and reattach.

After transferring Maysey’s iced appendage to a garbage bag — no room in the helicopter for the oversized blue barrel — his ride was quick. He was more worried about the view of the ground than what had happened at the factory. “I’ve made fun of him because he was scared of the helicopter ride,” says Alisa, who drove the length of I-65 to the hospital, her phone ringing with worried calls and messages. She arrived at the hospital after the surgery had started.

But her fiancé, who lives in Louisville, made it to the hospital in time to see Maysey surrounded by at least 20 OR team members examining the injury, prepping for surgery. The waiting room was already filled, an entire corner of the ER clustered with familiar faces when Alisa entered, faces she’d known from Lyons Missionary Baptist Church. She’d yearned for her parents’ support and wisdom on the drive up — both passed away in 2014, 45 days apart. She found it in her church community, in older couples who had acted as surrogate grandparents to her children.

“I realized that what I really wanted was just for him to be OK,” Alisa says. “When I say OK, I don’t just mean not die. I just mean spiritually. A lot of young men would get angry at God for something like this.”

The machine had fractured most of the bones in Maysey’s arm and hand, and the point of severance was an unclean cut. But first, blood flow. Galvis had never replanted an upper arm. He and two others rejoined the arteries to continue pumping blood to the limb, racing against that six-hour time frame. They plated the humerus bone with a bar of metal and screws, joining the two halves of the break. The surgeons lacerated the side of Maysey’s arm to reduce the swelling that occurred during transport, which could have led to compartment syndrome — a condition in which blood flow is impeded, that could have resulted in Maysey losing his arm all over again.

The surgical team had toiled in the operating room from 3 p.m. to 9 p.m., four hours longer than Galvis’ shift, when Dr. Huey Tien, another Kleinert and Kutz surgeon, took over the lead, working for another two hours. (Kleinert and Kutz hosts fellows from all over the world, already-practiced surgeons shadowing lead surgeons, learning the trade of microsurgery. Galvis, a former fellow, is a transplant from Colombia; Tien arrived from Taiwan.) After reattaching the veins, Galvis met with Alisa. In 10 minutes, he told her, they would remove the clamp on Maysey’s arteries. In 30 minutes they’d know if blood would return to his fingers. The team’s main goal in reattaching Maysey’s arm was to save his elbow, to give him that natural bend. Galvis told Alisa that he expected that blood would not return to the fingers, that they’d amputate as many inches away from the elbow as they could, and fit Maysey with a prosthetic hand. That 30 minutes became two and a half hours. Finally, Galvis relayed the good news. “We did some arterial sutures, and we saved the fingers,” he told her.

There are three nerves in the hand that control motion. Galvis and his team discovered that the nerve that controls wrist movement and hand closure was destroyed. But the nerve controlling fine motor functions — like pinching or writing cursive — was functional. So they made a switch, connecting the fine motor nerve to the end of the other. Since the replanting, Maysey has been in and out of the operating room. “In surgery every third day for the last month,” Galvis says. Now, back home in Glasgow, Maysey receives rehab, lucky that a semi-retired hand specialist lives there. Maysey will need to make periodic trips to Louisville. Right now, he’s working on moving his fingers, waiting to see if any feeling returns.

The patient: Dr. Dan Garcia, 68

The surgery: heart transplant

“Dr. Garcia, I don’t know you,” the woman began. Garcia had taken a phone call from a stranger in his home. “I’ve never met you. I’m in Bible study at Our Lady of Lourdes. Your patients have been praying for you to get a heart transplant for a long time. I know your whole story. I had a dream, and God said you’d get a heart transplant real fast.”

“Really? Well, that’s great. I really appreciate your prayers,” Garcia responded. He had been on the transplant list at the University of Louisville for five years. It was late 2015, and he had outlived the complicated implanted device routing blood through his heart.

“You’ve got to transfer all your care to UK,” she said.

“I can’t do that to all my faculty at U of L. I love my doctors. I love my hospital. I can’t do that.”

“I’ve had a dream,” she said. “You’re going to get a transplant real fast.”

A few weeks later, Garcia transferred his care to the University of Kentucky. Eight days after he was placed on the transplant list, he had a donor heart. An exact match.

It was an unusually chilly Sunday in April 1990 when a pain flared in Garcia's chest. He blamed it on the cold. “That happens sometimes,” he says. He and his wife had returned home from church. As he gathered the newspaper from the yard, the knot of pain expanded, deepened. He tried his inhaler — no go. EMTs drove him to Baptist Hospital, where he had a heart attack, his first. Two days later, surgeons opened his chest, operated on his heart. He had 97 percent blockage. A triple bypass, a cold recovery. A 10-day stay in the hospital, years in rehab.

Then: In the early hours of the morning of his daughter’s graduation from Vanderbilt in 2003, he woke up in a hotel room with a tight, oppressive pain radiating in his chest. His fingers on his wrist, his pulse erratic. His wife drove him across the street to the emergency room, where he stayed for 11 more days. “My heart was working so hard, it was like a can of worms,” he says. “My blood vessels were all shot. They looked like strings.” Through cardiac catheterization, doctors put in a stent.

In an office in the back of his Kentuckiana Allergy practice, Garcia flips a magazine over and draws a diagram. He makes an oval with two tubes at the top, an anatomical heart. He draws a couple of lines to represent the aorta, and a few more to represent arteries on the other side. He draws the left ventricular assist device, or LVAD, the machine that kept him alive for nearly six years. The device is implanted on the left side of the heart, where it creates a bypass to move the blood from the heart to the aorta, a detour around a construction zone.

“I knew I was in heart failure,” Garcia says. “I couldn’t catch a breath to brush my teeth.” His heart worked at 8 percent of its normal function at its lowest. He draws a larger circle around his initial drawing, saying that his heart was engorged. “They said my heart was the size of a football. It went from one side of my chest to the next,” he says.

He’d had a suspicion he’d eventually need his heart replaced — his mother, father and grandfather all had heart disease. Despite leading a fairly healthy lifestyle — a little extra weight, perhaps — he had his first heart attack at 42, and has had several other heart-related incidents since: A stroke. Cardiac stents. Arrhythmia. Cardiomyopathy after two bouts of pneumonia. A ruptured blood vessel from the LVAD, which moves blood but doesn’t pulse it. Garcia was put on the transplant list at U of L in 2010. Patients usually wait at least a year before a donor heart becomes available.

Dr. Mark Slaughter implanted the LVAD during a five-hour surgery in August 2010. After the procedure, wires protruded from Garcia’s abdomen and attached to heavy lithium batteries — or into the wall at night while he slept, necessitating the installation of a whole-house generator. Garcia cut holes in his pockets, looped the battery connectors behind his shirt and tie. An extra 10 pounds, batteries rotated every few hours, hidden. When he traveled, he made a spectacle at the security stops, sounding the batteries’ alarms — which usually warn of low power — and taking them out, proving their use. “My quality of life went like this,” he says, pantomiming a rising line on a graph with his flattened hand. “Then it went like this for a number of years.” The line evens out, horizontal. “Then my right heart failure started and I started going down.” His hand drops. His right heart failure caused lung hypertension — another high risk during surgery.

The estimated 12-month waiting period passed — fivefold. Two close calls: One heart came up, a match, but when the heart was tested — arteries inflated to check their usage — it was faulty. The next heart was given to Garcia by a family in his church whose grandson had passed. But it was too small. He attempted to switch his care to Vanderbilt, but they rejected his case. “Too old, too tall, too complex,” he says. But the device regulating his blood flow was not meant to last six years: There’s a 60 percent mortality rate after five years, 90 percent after eight.

Sometimes you have to advocate for yourself. Garcia says this several times. Being a doctor himself, he knows the right questions and when to ask them. He knows the shoptalk, the jargon. He does his research. “If I had not known about the heart-failure clinic, I would probably be pushing tulips right now,” he says.

Sometimes advocating for yourself means listening to prophetic phone calls. Garcia drove the 75 miles to UK on a Friday afternoon in January just to see what specialists there had to say. If they gave the same prognosis as Vanderbilt, he’d live with it. After all, the University of Kentucky and the University of Louisville pull from the same procurement pool. “I had a mindset that I was going to live maybe two or four years, and that’s it,” he says. “I was trying to get some things in order.”

Back at home, after the consultation, Garcia was passing time before a planned movie date with his grandchildren, twins. His wife was sewing. It had been only a week since he’d added his name to UK’s transplant list when he got the call. “We’ve got a heart for you,” a nurse said on the other line. “We need you here within three hours.”

“I wasn’t ready for it,” Garcia says. “I thought it was going to be another month, or three or four, or another year.” They’d had their bags packed, waiting — a change of clothes, toothpaste, deodorant. “And my curling iron,” Garcia jokes. Tracing their path from a week earlier, Garcia sent messages to his family while his wife drove — prayers and gratitude, all good vibes. Garcia says he felt confident on the journey. “One way or the other, I was going to win,” he says.

The University of Kentucky is aggressive in searching for donors. It will take hearts that might be at the edge of optimal, ones that other places won’t accept. “Typically the ones that have been turned down by other people are usable if we have time to manipulate the donor’s criteria before the harvest goes on,” says Dr. Michael Sekela, the lead surgeon for Garcia’s transplant. The donors he’s talking about are typically patients declared brain dead. “Dr. Garcia was up in years and had other issues that made him high-risk, but we had a donor that would fit him that nobody else would use. But it’s really not the edge of what you can do with donor (hearts). Those donors work out just fine if you take some time to get them better.” The UK heart transplant team has performed nearly 30 operations. Their first year survival rate is above 90 percent, higher than average.

Sekela says Garcia’s transplant was fairly standard. “Just the usual stuff. Tough getting in, tough getting out.” Blood and nicotine tests, a surgical staph bath, a psychological test, echocardiogram, kidney and pulmonary checks and X-rays before anesthesia. The most complicated part was coordinating the extraction and transport of the donor heart with the removal of the assist device and the patient’s heart. In a span of 12 hours, the surgical team cracked his sternum, revealing the heart and the LVAD, connected in two places. Scar tissue had built up around the LVAD device, the toughest part of the surgery because scar tissue means bleeding. It took eight hours to remove the LVAD.

The surgery is a matter of arrangement: extracting the heart from the donor soon enough to transport — the organ, on ice, traveling by jet with a handler — to the operating room without having the patient waiting on bypass support for too long. But not so soon that the donor heart sits unconnected. From the moment of extraction it begins shutting down. The longer it takes for the heart to reach the recipient, the higher the chances of graft dysfunction, of rejection. But it can’t arrive too late into the process of LVAD removal, lest something happen during transport of the donor heart, and the LVAD needs to be replanted. “That’s the toughest part of the operation,” Sekela says. “Once the heart’s in the operating room, putting a heart in is really not technically difficult.”

Garcia woke up in Colorado, thinking he was standing in the snow-capped mountains, hearing John Denver, remnants of his honeymoon camping in the Rocky Mountains. “I didn’t know whether I had died or not,” Garcia says. “I thought maybe I had died and I was entering heaven.” But his periphery trickled in; his wife, Rita, his children and grandchildren stood next to his bed. On the bed tray was a laptop, a homemade slideshow of Estes Park and the Smoky Mountains. The stranger whose dream pushed Garcia to pursue treatment at UK was in the waiting room.

His fingers found his abdomen — no more LVAD wires. Moving up to his chest, he felt where they had cracked his rib cage to place a beating heart that used to belong to a woman. No longer would his pockets be filled with the sagging weight of batteries, charging ports scattered throughout the house and office. The generator would become a convenience, a way to keep the fridge running in a power outage.

His first directive: get moving. “Every day you’re in bed, it’s going to be seven to 10 days recovery,” his doctors said. Day two: Twenty steps with a posse of nurses carrying fluid bags, oxygen. “I looked like I had a whole ICU with me,” he says. Days later, laps around the nurses’ station. Moving was hardest, going from couch to chair, lifting out of bed — always too little breath, too little stamina. But after months of cardiac rehab, Garcia can walk two miles, nonstop.

Seven weeks is the magic number, the goal of recovery. Garcia spent 17 days in the hospital ward. Behind his bed was a mural — painted mountains and calm streams. A couch pulled out into a bed for visitors. His window faced south, catching natural sunshine and students on campus. He rented an Airbnb home five minutes from the hospital to make his frequent outpatient checkups.

After months of cataloging medicines in an organizer, monthly heart catheterizations and drives to Lexington, Garcia says the biggest change is warmth — in his hands, his feet, his bald spot. His muscles aren’t achy. “You know the feeling you have before the flu? I always had a touch of that,” he says. “Looking back, it’s like a whole new chapter for me. They did a good job on me.”

Garcia is in the process of writing a letter to the family of his donor. “A lot of people go through guilt or depression (after a transplant),” Garcia says. “I never had any of that. I see it as a great gift. I think it’s very generous to give a heart.”

The patient: Trinity Goodson, 14

The procedure: bone-marrow transplant

“Trinity’s rapidly approaching two and a half years post-transplant, and she’s still not been back to school,” says Laura Goodson, Trinity’s mother. “She doesn’t go anywhere except the doctor.” In the four years since Trinity’s diagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2012, they’ve seen a floor nurse at Kosair Children’s Hospital — the very first nurse who administered Trinity’s chemotherapy — go through promotions; now she’s the assistant nurse manager. Trinity hasn’t been to school since Nov. 19, 2013.

The only red flag was weight loss. Trinity lost four and a half pounds in about 10 days. She was sleepy and wheezy, but had been diagnosed as asthmatic in 2003. Days prior to the weight loss, she mentioned an achy shoulder. A 10-year-old with growing pains, her mother thought. On June 21, Trinity’s grandfather, watching her for the day, told Goodson, “She’s only had about three bites from an egg and cheese sandwich today.” She’d only had about six ounces of water.

Later that evening they drove her to an after-hours clinic near their home northwest of Louisville in Pekin, Indiana, run by doctors that Goodson, a nurse, worked with. They first listened to her lungs, heard near silence on the left. Another red flag. “Why it never dawned on me to listen to her lung sounds I have no idea,” Goodson says. A breathing treatment didn’t solve anything. They drove to Harrison County for chest X-rays. Goodson, who had sat with a heavy lead apron through many chest X-rays with Trinity, was pushed into a viewing room with her husband. The X-rays came up on the screen. “Anyone would have known something was wrong,” Goodson says. The right lung was white. The left lung black. Back to the immediate-care center. The doctor said, “I don’t know what’s going on with your child. I could waste time trying to figure it out, but she doesn’t have the time to waste.”

“Can’t we drive her down to Kosair?” her husband asked.

“You don’t understand,” the doctor said. “She doesn’t have 30 minutes to waste.”

Goodson packed clothes at home, kissed her other two children while her husband rode in an ambulance with Trinity to Kosair, where a chest CT revealed fluid and a mass.

The fluid had deflated her left lung, moved her heart, pushed her diaphragm into her stomach. Excess fluid pooled around her heart and was starting to attack her right lung. Doctors drained 1,500 CCs for biopsy. Another 1,000 drained from a chest tube. That big plastic bottle of soda at the grocery store? That’s slightly less than the amount of fluid drained.

They had arrived at the immediate-care center around 6:30. It was nearly eight hours later when the doctor at Kosair led Goodson and her husband to an empty room, made them sit. He said that Trinity had cancer. They were almost certain that it was lymphoma and would know for sure later that afternoon, after testing. “I can remember walking through the hall as a zombie when I first heard the words,” Goodson says. “In the beginning, I felt so alone.”

But the Goodsons haven’t been alone. In her time at Kosair, Trinity has met other children — different diagnosis, perhaps, but same journey, same feeling of abnormality. You get close to families, trade shoulders to cry on. In Trinity’s four years of treatment, she’s lost some friends. “You never think that your kid is going to have to go to a friend’s funeral so young,” Goodson says. Trinity wanted the closure, attended the funerals if she could.

Even in the midst of tragedy, support continues. “All the new families,” Goodson says, “I’m able to tell them, ‘This is a club that you never, ever, ever want to be a part of. But once you’re in it, you’re in it for life. You’ll always have someone on your side.’”

Trinity’s fears upon hearing she had cancer were about missing school and losing her hair. “She had four people at school that actually shaved their head for her,” Goodson says.

Angus has been with Trinity since just after her first surgery, the first of many long nights and hospital stays. Angus is a stuffed frog, given to her by a friend’s brother. Trinity’s immune system is too weak for visitors. When arranging the interview for this piece, Goodson and I settle on a phone conversation. When her sisters, one older and one younger, arrive home from school, Trinity is confined to her room until they have showered and changed, removed any bacteria or viruses from the outside world. Her younger sister, now nine, has been going through this routine since kindergarten. “It’s an ongoing joke with her,” Goodson says. “We have to ‘de-cootie-fy’ from school.”

The Goodson household has three high-efficiency filters, an electrostatic unit on the furnace, ultraviolet light to kill bacteria. “Before I was even allowed to bring her home, when she finished with (a bone-marrow) transplant, I actually had to have Coit cleaners come out and clean my ductwork,” Goodson says. Carpets were sliced from the floors to diminish stirring up dust mites and worse. When Goodson cleans the house with a mixture of alcohol and water, Trinity must stay in her room, avoiding the upswept dust. When Trinity first came home from the hospital, Goodson would change bed sheets daily, now does so weekly. Angus gets a bath once a week.

Trinity rides to the doctor in a car for that purpose only — wiped down with the alcohol-water combo once a week, packed with clothes for her and Goodson. Designated last-minute bags stay in the house — for medicine, books and Angus. “We don’t have two of Angus,” Goodson says. “So Angus is one of the last things that gets thrown into her bag.”

“It’s actually quite underwhelming,” says Dr. Alexandra Cheerva, Trinity’s oncologist from the beginning. “There’s no surgery involved. They don’t have to go to any special room.” A bone-marrow transplant is like a blood transfusion. An intravenous infusion through the central line, like a catheter — Trinity’s in her chest — and the donor marrow is transplanted. For about an hour or two, Trinity only needed to sit in her patient room, decorated blue and lime-green, perhaps taking medication for slight nausea.

Trinity’s initial donor (neither sister was a match) started with a simple cheek swab to test for her human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing, a protein marker that must match the patient’s. Donors are on a worldwide registry. When doctors need a donor, they check the database, receiving basic information: matching HLA, gender, approximate age. Both Trinity and her donor were tested for illnesses or complications in the week prior to the transplant date. That donor postponed, then backed out. They secured a second donor. (For a year after the transplant, neither the donor nor the Goodsons could make more than anonymous contact, per the registry’s rules.)

Before the transplant, Trinity received high doses of chemotherapy and radiation to attack the cancer cells, leaving her in a “blank” — but very fragile — state. The donor bone marrow, or stem cells, provides white and red blood cells, as well as platelets. Usually, transplant recipients are immunosuppressed for about a year, a period in which they are susceptible to viruses, bacteria, germs. A week before Trinity was set to receive her transplant from the second donor, a nasal swab tested positive for a cold-type virus usually found in newborns. “All the chemo that she had basically killed her immune system so much that that’s basically what she was, a premature newborn,” Goodson says.

This road, these past couple of years post-transplant, have not been easy for Trinity. “It’s been a long and complicated journey,” Cheerva says, one that included brain surgery after an infection. Surgeries to put in a central line, like a more permanent IV, or her port — a harder-to-access-but less-obtrusive line inside her right rib cage.

Her immune system has improved over the two and a half years since her bone-marrow transplant, but not enough. After a stem cell boost in early June, her CD4 count, the measure of her immune cells, was up to 200. (Cheerva estimates a normal range would be close to 500). “I thought everybody was going to go dancing in the streets,” Goodson says. “Everybody thought that Dr. Cheerva was going to do a jig in the hallway.” As of press time, her CD4 count was roughly 350. With a count higher than 200, doctors can begin decreasing medication — the slew of antivirals, antifungals, immunosuppressants — and get on the road to immunization. On the road to school.

Kosair hosted a pre-transplant party for her. “Pre-transplant,” because, as Goodson explains, “You never know how long it’s going to be before these kiddos are going to be able to be around a group of people again.” Trinity chose food from Texas Roadhouse. A plethora of cake and ice cream, gifts. Other families and children they’ve met at Kosair, the families and children who can most identify with Trinity’s journey, celebrated with her.

Post-transplant, Trinity was lucky to avoid an extended stay in intensive care. She couldn’t have fresh fruit or vegetables — too much bacteria. No pepper because it harbors aspergillus fungus. The meals she ate had to be completely consumed within an hour of preparation. Most transplant patients are fed through a tube. Post-transplant, Trinity’s body was recovering; she was tired.

Now, Trinity is spunky. “We would always tell the doctors since transplant that we missed our happy, bubbly girl,” Goodson says. “We’re finally getting her back.” If Trinity’s older sister complains of a headache, she’ll say, “I dealt with headaches for three months and nobody knew what was going on with me. Cry me a river.”

This originally appeared in the August 2016 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find your very own copy of Louisville Magazine, click here.