By Chris Kenning

In the sober morning light at Air Devils Inn, Gloria Bramer jabs a key into the lock of a battered side door with peeling paint, a door that interrupts a mural of vintage military fighter planes. Out front on Taylorsville Road, across from Bowman Field, the sign for band listings reads, “Happy Birthday Gloria.” She just turned 70.

Once inside on this Tuesday, Bramer flicks on the lights and passes an orange bumper-pool table, a mounted snarling hog’s head and dusty model airplanes hung from the ceiling. The place smells like last night’s beer and feels like it might still have a hangover. She walks behind the bar, where the sinking floor is causing shelves, already groaning beneath the weight of bourbon, to slant worryingly toward a collection of beer taps in the middle.

The low winter light illuminates the Air Devils oddities — the black-and-white 1940s photos of men drinking beer; the red leather booths; the pictures of fallen patrons, like Bambi and Spaghetti Joe, taped to the bar mirror. A TV sits beneath a shelf that holds everything from a 1962 Oktoberfest mug to a 1991 Indy 500 beer can to an early-’60s novelty doll called a Charlie Weaver Bartender. The old vending machine contains, inexplicably, a lava lamp, an asthma inhaler, an empty pack of Camels, a bikini mug and a Three Stooges tie.

It’s nearly 10 a.m. Time to pull the cash drawer. Turn on the neon beer signs. Unlock the front door next to the long-dead pay phone. Turn on the TVs. Bramer, the early-shift bartender, wakes up the old bar for another round.

Behind-the-bar photos of deceased patrons, including Bambi (center).

Bramer, a blond former sales rep in jeans and tennis shoes, surveys the mismatched decor, the grime and the checkered floor full of holes. She sighs. Sometimes the place feels like it’s falling apart, she says, sounding like a homeowner apologizing for the mess. But she knows the nonchalant decay has also given Air Devils the ne’er-do-well, ornery outlaw vibe that appeals to die-hard regulars and dive-loving newcomers. “I like it the way it is, to be honest with you,” she says.

The door creaks open. It’s Gabe, a white-haired, 85-year-old former accountant. He’s usually the first to arrive. He likes to watch Gunsmoke reruns on silent because he knows them by heart. The bar keeps peanut butter crackers and hot pretzels in stock just for Gabe. He hauls himself onto a stool and orders a Miller for $2.50. After his first long pull, he sets the bottle down slowly next to his pile of dollars and two quarters. Others begin rolling in, the usual crowd of 10 or so who are closer to friends than patrons. One guy orders a Coke. His taste for gin and tonics got out of hand.

|

| The bar keeps peanut butter crackers and hot pretzels in stock just for Gabe. |

“How about a Bloody Mary?” one man says to Bramer. He lobs out observations that spark old-man talk about Clemson beating Alabama, health woes and the clear but cold weather.

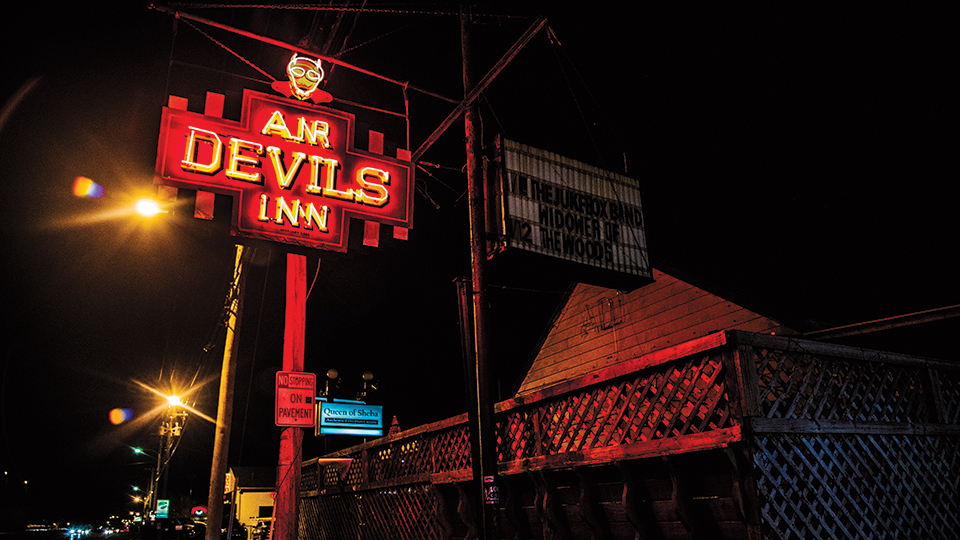

The first of three bartending shifts is underway at Air Devils Inn, Louisville’s most storied and historic dive bar, known by its iconic neon sign topped with a devil. It has no phone, no kitchen. Bartenders serve strong and cheap drinks that one guy jokes often contain three ingredients, including the glass and ice. This year, Air Devils marks its 85th year in operation. Its history includes barnstorming pilots, wartime dances, illegal gambling, roaring motorcycle clubs, sweaty music nights, love both lost and found, and a nearly 25-year-old murder that still haunts the place.

Alan Downie is a 67-year-old longtime bartender originally from Scotland. He sports red hair, sideburns and a Hawaiian shirt. “It never ceases to amaze me,” he says. “People come in and say, ‘Oh, man, I haven’t been here in 30 years and it looks just the same.’”

Air Devils Inn, or the Devil, or ADI — depending on how regular you are — began its life as a one-room schoolhouse. The Maple Grove School was built in 1876 on a rural stretch of cattle pastures and potato fields. One old photo shows two-dozen children, some wearing round eyeglasses or knickers with bows, posing grim-faced next to a teacher out front. But it was the 1921 opening of Bowman Field, the state’s first airport and the oldest continually operating commercial airfield in the United States, that eventually fueled the bar’s rollicking history.

After the school consolidated with Melbourne Heights and Alex R. Kennedy schools, the building sold in 1926 for $8,500. For a time, it served as an Army Signal Corps chapel. It was a social club called Castle Gardens. In 1934, a year after Prohibition ended, Air Devils Inn was born.

Bowman Field still had a dirt runway then but served as an Army Air Corps depot, an airmail terminal and a passenger airport for fledgling commercial air travel on Trans World and other airlines. Amelia Earhart made an appearance at Bowman Field, and in 1927 Charles Lindbergh landed his Spirit of St. Louis, drawing nearly 10,000 spectators. “He did a radio interview,” Downie says, then spreads lore in true bartender fashion. “And apparently the last question was something like, ‘When you get done, what are you going to do?’ He said, ‘I’m going to Air Devils Inn to get a drink.’” (Air Devils wouldn’t open for another seven years.)

Air Devils served as a watering hole for crowds who flocked to Bowman to watch aerial exhibitions of stunt flying, parachute jumping, air racing and skywriting. Some came to see planes land near the Art Deco terminal, which could have been a stand-in for a Casablanca movie set — and, in fact, was later used in the 1964 James Bond movie Goldfinger as the site of Pussy Galore’s Flying Circus.

During WWII, Air Devils got another big boost. Bowman Field’s role as a key military training base made it one of the nation’s busiest airports. It was home to a bombing squadron and basic-training personnel, including flight surgeons, medical technicians and flight nurses. Couples came to the bar for big-band music and an outdoor beer garden. A latticed bandstand overlooked a large maple tree by a smooth terrazzo tile dance floor, which a 1930s newspaper ad called the “South’s finest.” “It had a well-known dance floor,” says patron Jim Murta, who served in Korea and is a regular.

By the late 1940s, the city was trying to rid bars of illegal slot machines, and the Courier-Journal twice sent reporters throughout town to see if the effort had been successful. Air Devils still had two slot machines, one costing a nickel per play, the other a quarter. Players hoped for cherries to turn up. “It’s due to hit,” a middle-aged man assured one reporter. Air Devils Inn was also where the “Case of the Disappearing Legs” was solved, according to a 1953 C-J story. A night watchman heard a noise and saw legs disappearing into the bar’s ceiling. He fired two shots and called police, who later arrested two brothers. They were discovered with plaster and cobwebs on their feet from where they’d broken in.

Former sales rep Gloria Bramer mans the first of three bartending shifts at Air Devils Inn.

A 1969 newspaper ad called Air Devils the “Home of the Big Band Sound,” with cocktails by “Louisville’s top mixologists.” More than a decade later, the bar still had the best big-band jukebox in town. According to a C-J article: “Walk in the front room, drop some quarters into the machine, punch up some Benny Goodman or Artie Shaw, and all of a sudden it’s 1942.” (Air Devils was apparently a C-J hangout. One piece praises a bartender for putting up with the newspaper staff’s “lunatic fringe.”)

In the 1980s, a Vietnam War veteran named Daniel Shockley decided to purchase the bar, its building still owned by a landlord. Shockley, whose legs were in braces after the war and who was later paralyzed after falling off a ladder, wanted to make the place a home for great music. And he saw that things were changing. “Little joints like this are a vanishing breed,” Shockley told Downie. “In the near future, it’ll all be Applebee’s, where they pull up with a tractor-trailer full of memorabilia, and they create the atmosphere rather than have it naturally happen.”

Shockley, who was known for vaulting himself onto a barstool, became the Air Devils Inn’s welcoming face. Today, his painted image is wedged in with Jimi Hendrix and Ray Charles. “People loved him,” Bramer says.

The daytime regulars — who profess to have no idea what happens at night at Air Devils Inn, since they’re never here that late — agreed. Then they grew morose. One leaned in and whispered, “You know what happened to Dan, right?” before declaring he didn’t want to talk about it.

Late owner Daniel Shockley.

By 11:30 a.m., down the bar from a half-dozen older men, 63-year-old Mike Kinberger sips a bottle of light beer. He says he comes in around noon and drinks a couple of beers. He likes the daytime crowd. “Everybody just bullshits with everybody,” he says.

Kinberger gets to talking, peeling back a life story between drinks. He got a job as firefighter in 1978 for a $14,500 salary. He had fun. Things were looser then. Guys brought women to the firehouse — though, he says, not him. He was only scared on the job once. That’s when he found a woman in a house fire who looked like a burned-up mannequin in a chair. “Had an oxygen tank,” he says of the woman. “It caught on fire and burned her up.”

Kinberger had kids and retired at age 45. Now he spends part of the year in a mobile home in Avon Park, Florida, either by the pool or hanging out at the Moose Lodge. He says he’s just gotten back from the doctor. Pancreas issues. The doctor ordered him to drink fewer beers each day. Kinberger says the doctor told him to “cut it down to four, and we’ll try that.”

Not long after noon, owner Russell Shockley — Dan’s son, he himself now 51 — strides in wearing a backward baseball cap and carrying a slow cooker full of pork shoulder. He’s got buns and paper plates. Another free meal for patrons. Shockley, who owns the place with his wife Kristie, is beloved, just like his late father. Why? One patron has an example teed up. He once pumped gas nearby without realizing he’d forgotten his wallet, so he called Shockley. Because who else would you call? Shockley left the bar, paid for the man’s gas and gave him $20 to come drink.

Shockley’s not a fan of the media, for reasons that will come out later. He doesn’t want to talk. He and Kristie do tell me that they still lease the building and operate with about nine employees (some, like Downie, now only work one day a week). But Shockley immediately says that he wants to sell the bar.

The consensus is that if a TV show like Bar Rescue showed up, Air Devils would be ruined. “They’d have a lot to say,” Downie says. “You do what you can. It’s the kind of situation where, if you clean up a certain section, it just makes whatever is beside it look worse.” Shockley does say his wife wants to keep the bar, so she has taken on more responsibility. But it’s a struggle he’s tiring of: Doesn’t own the place, can’t afford a major renovation. A job with a steady paycheck would be nice. “You get a couple hiccups, and it’s, ‘Are we paying the lease or the mortgage?’” he says. “It’s way too much stress.”

|

| From left, bartender Gloria Bramer, co-owner Kristie Shockley and bartender Alan Downie. |

That stress grew after the demise of the weekly biker nights that the bar became loved and hated for, depending on whether you owned a bike or a nearby yard. Each Thursday in the ’90s and early 2000s, the bar would welcome growling Harley Davidsons, “a cross-section of Louisville that will include stockbrokers, mechanics, doctors, local businessmen, the occasional nurse, the moneyed and the tattooed,” according to the Encyclopedia of Louisville. “By 8:30 p.m., the unconventional convention is on the road, happily Harleying down the highway.” Some called it the “dusk patrol.” Once, the bar hosted a biker wedding in the parking lot, covered live by a TV reporter.

But complaints from neighbors led to a city crackdown. Shockley says he still blames one vociferous neighbor, a city inspector he believes had a beef with the bar and a reporter who wrote about it. I read one story, which seemed pretty tame, but that’s not how Shockley remembers it. “It wasn’t the Hells Angels or Grim Reapers; these are people who drive motorcycles on the weekend,” Shockley says. “But, oh, man, if you’d read any of those articles, you would have thought there were knife fights and shootouts up here and all kinds of horseshit.” Russell has to run off to deal with an order and refuses to be photographed. His wife leans in. “He’s a negative Nellie today,” she says, noting that, so far, they haven’t received any sufficient offers to purchase Air Devils. Besides, she’s hopeful that things can work out. She has plans to turn part of the bar into a speakeasy, a nod to its past. “We can turn it around,” she says. “It’s been a bar for 85 years.”

By 2 p.m., 43-year-old Jennifer Frames shows up behind the bar for a shift that will last until 8 p.m. The last of the morning crowd is gone. When Kinberger left, he said, “I’m going to take a nap.”

Frames, in a flowered sweatshirt and jeans, started bartending here in 2002. She was a struggling single mom in her 20s. She says her kid’s father had gotten into trouble and was gone. She was stressed out, working at a plumbing supply company and badly in need of a second job. “Everything crumbled, and I crumbled,” she says.

At a low point, a friend suggested that Frames take an open bartending spot at Air Devils. She wasn’t so sure but showed up anyway to meet with Russell Shockley. “I remember parking outside and thinking, ‘Whoa, what am I doing? This is crazy.’ But I go in and it’s all dark. Russell was in here,” she says.

She said to him, “I’m kind of looking for a part-time bartending job.”

“Oh, you got any experience?”

“No.”

“Well, when can you start?”

Frames quickly learned tips — like don’t pour out somebody’s booze-marinated ice — and suddenly realized she had been taken under the wings of seasoned pros and had a new group of friends, including bartender Belita McDonald. McDonald is now 58 and does catering for private jets, including once for Fleetwood Mac (Christine McVie had a salad and chicken) and Kid Rock (a fan of lobster). McDonald is coupled with an Air Devils regular who she says wore down her policy of not dating customers. He used Kris Kristofferson lines on her.

Frames leans on the bar, says some of the workers and patrons are “closer in this family than their own families.”

“When I started working, this lady told me, ‘Welcome to Air Devils. It’s like Hotel California: You can get in but you can’t get out,’” Frames says. “And I still think about that to this day. Well, here I am. I totally got sucked in.”

During an afternoon lull, Frames walks past the bar’s Golden Tee arcade game and a small ATM, pushes through the prone-to-slamming front door and lights a cigarette on the deck scattered with weathered wood furniture. The bare frame overhead once held an awning. Cars whir past. To one side of Air Devils is a liquor store, to the other a sushi restaurant that was once a Frisch’s. Frames takes a deep drag. She says she grew up “a little sheltered, a little privileged, maybe a little shallow or judgmental.” She has spent time with patrons “from doctors to almost-homeless. That really humbled me. I learned more through working here than I could ever learn at any school.”

The after-work crowd arrives not long after 6 p.m. Pool balls crack. The average age is starting to fall, if only slightly. The pork is still on.

Frames opens and shuts the white refrigerator covered in stickers from Nolin Lake, pictures and postcards, a random mishmash that wouldn’t be out of place in your kitchen. She’s pouring shots of bourbon and Fireball, popping light beers. The digital jukebox plays the Rolling Stones song “Waiting on a Friend.”

A Hikes Point man gets his first drink before his night shift as a bartender at another place. He says he got weird looks as a new guy when he first started coming here. Not anymore. “I can name everybody except one guy and the dark-haired girl,” he says, pointing. “You got Carl. You got Duke. You got Mark. You got Gary. You got Dave. You got the other Mark. You got Ben. The guy wearing the hat I don’t know. And that’s Eric at the pool table.”

A few feet away, 63-year-old Vince Alexander sips a shot of Fireball and a Bud Light, a cigarette behind his ear. He’s teaching me how to bank pool shots on a bumper-pool table. Alexander, a retired carpenter who works at UPS, was born to military parents in Germany. He says for a long time he was one of the bar’s few black patrons, partly because the biker nights made some nervous. He says Dan Shockley welcomed him. “He knew I was uncomfortable, and he said, ‘I don’t see color. The only color I see is green,’” Alexander says.

Alexander looks melancholy. He mentions his wife of 34 years, who passed away some time ago. Over the years, some guys didn’t want to invite their wives for drinks after work, but he always did. He couldn’t wait to see her. He says Judy was his soul mate. He looks away. “Everybody should have that.”

The darkest chapter in the bar’s history — the incident everybody brings up but tells me not to ask Russell Shockley about — happened on a December evening in 1995.

That night in the bar, an EMS worker named Richard Clem was being loud, erratic and belligerent, according to a story. Dan Shockley tried to eject Clem, and, for some reason, Clem dropped to his knees. “Dan, I want to stay — please let me stay,” Clem said, according to the story, which was based on interviews with witnesses. Shockley told Clem to leave and that he could come back later. Clem walked out, kicking a booth. He returned with a 9mm handgun.

“He’s got a gun!” a witness yelled, sending patrons scattering, according to the story. Bramer fled to the women’s restroom. Clem shot Dan Shockley and another patron, a welder named Walter Means. Both died. The assailant, who was thought to have a mental illness, drove away to his nearby home, stopped his pickup in the driveway and shot himself dead. Russell says coverage of the event wasn’t accurate but won’t elaborate.

“Tore everyone up,” one patron says. “Senseless.”

Twenty-nine-year-old bartender Mikey Norris arrives at 8 p.m., and Frames packs up to go home. Norris’ shift will last until 4 a.m., which could bring him anywhere from $50 to a couple hundred bucks. He’s a big guy in a T-shirt, a silver neck chain, a baseball cap and a cast on his arm. About the cast, he says, “I got jumped by three dudes.” This was outside another bar. “Fought them off, though,” he says.

New arrivals begin walking in with guitars. They unpack velvet-lined cases in a corner near a low-lit booth. Musician Nate Thumas, wearing an Army jacket and Chuck Taylors, is writing down names for the open mic he runs.

In the 1990s, Air Devils was a wellspring of local music, evidenced by the stickers of Louisville acts that dot the walls around the stage. Dallas Alice, Tim Krekel, El Roostars, Ultratone, Johnny Berry, Squeeze-bot, Satchel’s Pawnshop. Hip-hop group the Villebillies often played at Air Devils and once shot a music video here, erecting a Blues Brothers-style chain-link cage around the stage that remained for years.

Bartender Mikey Norris and the late-night crowd.

One night years ago, Downie recalls, Hank Williams Jr. and his backing band, Bama, arrived after a show at Freedom Hall. A local musician made it clear that Hank Jr. didn’t want to be bothered by autographs or requests. Bama ended up onstage without Hank Jr., who sat in a booth. “At the end of the night, someone came over and said, ‘Man, Hank Jr. is pissed. Nobody asked him to play,’” says Downie, who shot back: “Hell, you told us not to!”

By 9 p.m., a series of musicians are behind the mic covering Jim James of My Morning Jacket and John Prine. There’s a black comedian, a white rapper and a singer-songwriter couple who cover the Pussycat Dolls song “Don’t Cha.” Watching are musicians such as 71-year-old Denny Wheatley, who hands me a copy of his album Blame It on the Whiskey. He never made much money in music. “I got a check for downloads for $9.99,” he says. “They wanted $10 for signing it.”

An older guy with a gray beard is dancing with his girlfriend, her hands in the back pocket of his jeans. They stare into each other’s eyes, dancing and kissing. Everyone watches, envious of their oblivious attraction. “She’s a force of nature,” the man says as he grabs a drink at the bar, smiling as he watches her dance away and hug a friend. “She makes me so happy.”

Near the end of Thumas’ list is Bill Ede. He has gray hair and looks tired from working nights at the post office. One patron had said, “You should talk to Bill. He’s an encyclopedia of music. But make sure you have lots of time. He can talk.” Ede grew up loving music. He was a fan of singer-songwriter Roger Miller, learned to play guitar, listened to music like it was his job. “I thought it was going to lead to something,” he says. He did odd jobs, including selling the C-J at a stand on Oak Street, and wrote heartbreakingly good songs. He eventually took a job at the post office to make ends meet.

An older guy with a gray beard dances with his girlfriend. "She's a force of nature," he says.

Onstage, he sings some of his music from a career that never took off as much as he’d hoped, which seems crazy to the 20 or so listeners at Air Devils. They are rapt, listening to Ede’s music that is both poignant and wrenching. “I’m not going to rock the boat until my ship comes in,” he sings in one.

He also covers the John Prine song “Far From Me.”

And the sky is black and still now

On the hill where the angels sing.

Ain’t it funny how an old broken bottle

Looks just like a diamond ring.

Open-mic night finishes after midnight, and Downie walks to the jukebox. His recent bout with cancer has made him more difficult to understand when he talks, but that hasn’t dimmed his boisterous spirit. He selects more Prine, this time “Angel From Montgomery.”

By 2 a.m., the crowd has dwindled, the jukebox gone silent. The older dancing couple got an Uber home. The musicians packed up their guitars.

Now it’s just Mikey Norris, sitting at the bar near one of two biplane lamps that hang at either end. He lights up a smoke since nobody’s around and recalls how the bar’s ornery nature meant it was among the last to give in to the city’s smoking ban.

At this late hour, sometimes a taxi full of drunk young women will suddenly pile inside, fire up the jukebox and start buying shots. Norris hears a noise, but it’s no one. “All the doors creak a little different. The front one slams, so you know,” he says. He gets to talking about the occasional fight or when he has to intervene in “yelling and standard bullshit.” When he must, he’ll make it sound like the troublemaker is really putting him out. “You’re really going to make me call the police?” he’ll say. “You’re going to do that to me tonight?”

He glances at the bar clock’s digital red numbers: 4 a.m., closing time. But the clock is set to “bar time,” meaning it’s actually only quarter ’til. He pulls out the tip dollars from the jar. Not bad. Then it’s time: Wash the glasses, stock the beer, clean the slow cooker, wipe the tables. The place can frustrate Norris, but it clearly means a lot to him. “Places like this just don’t exist anymore,” he says. “At least there aren’t many.”

He has another smoke, this time outside. The lights of Bowman Field flicker across the street. He still needs to switch off the lights and lock up, leaving things ready for Gloria Bramer. She’ll be back in a few hours.

This originally appeared in the February 2019 issue of Louisville Magazine under the headline "Running with the Devil." To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Photos by Mickie Winters, mickiewinters.com