Ray Carden lights another Red Buck filtered cigar, looks at the TV. The screen’s colors are washed out, Fox News dim. Ray doesn’t mind the tone but sometimes wonders why they call the news the news. You see the same things today you saw yesterday. It’s over and over. Lately it’s that Germanwings plane crash, the co-pilot committing suicide and taking 159 or however many down with him. Horrible, yes, but good God, they’ve talked it to death. Now they’re talking about what motivated the co-pilot to do it. Got all these experts weighing in. When they say experts, ain’t no telling what you’re gonna hear. Experts!

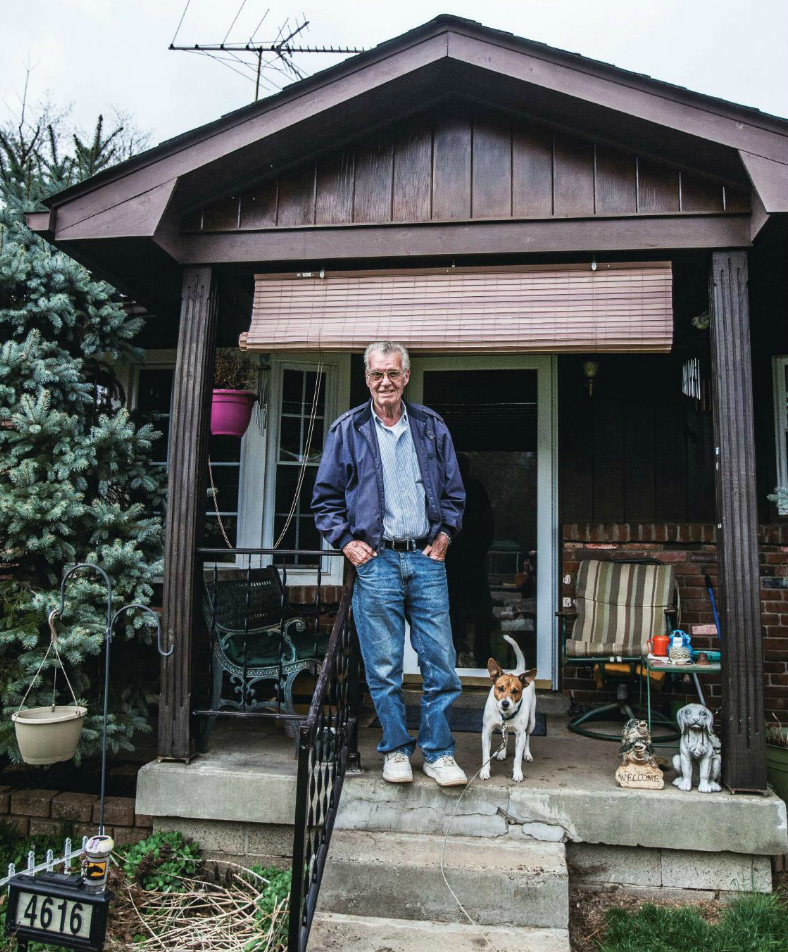

When he was young, Ray was an expert builder, like his grandfather, father and uncles. It’s what he grew up with, knew how to do. He’d work the saws with the men, and when he turned 16 he ran the framing business for his dad. Kept on building well into his 20s and 30s, even with a full-time job at Ford Motor Co. Too old for all that now, though. Frances Ralph two doors down jokes he’s a crotchety old bastard, older than dirt. If someone talks about the Civil War, they say, “How ’bout it, Ray? You were there!” He laughs, but he’s not that old, just 78. Gray hair, thick glasses on a long face, body tall with a spine still straight even when sitting, which he’s usually doing, on his leather couch, or in his sunken recliner, or on the front porch drinking coffee. Maybe he doesn’t get out too much, but he can still drive his little GMC truck, no problem. He’ll go to the grocery in the morning, or every so often to see his kids, or down to Frances’ and Gerald’s, or out to Cracker Barrel to meet his brothers for a 10 o’clock breakfast. They just started that, the once-a-month breakfast club.

Ray could’ve built his house anywhere. Was building for folks way out in Oldham County, all up and down Dixie Highway, a lot of houses in the Cloverleaf Acres subdivision, and even across the river, in Palmyra and Paoli. But he chose Lake Dreamland, a neighborhood in southwest Louisville bordered by Camp Ground Road and the Ohio River, because it’s home, basically always has been. Ray spent his 10th birthday in Lake Dreamland. His family moved here when his dad returned from World War II, less than a year after it ended. A lot of people were moving into the neighborhood then ’cause it was cheap. Six-dollars-and-twenty-five-cents-a-month cheap, taxes way low.

Why so cheap? Because of a dream tried and failed and flooded and trapped. An old dream, before Ray’s time, but all around Lake Dreamland. In the mind and then the hands of developer Ed Hartlage. Hartlage’s 1930s dream? A summer resort. Lake Dreamland. A getaway, escape from reality, a retreat for Louisville’s elite. Lakeside cottages, horseback riding, swimming, fishing, boating. Critics told Hartlage his idea of turning the dairy farm into a resort would never amount to anything, the plan too ambitious, merely a dream. All the more reason Hartlage dammed Bramers Run in 1931, creating Dreamland Lake, leasing the waterfront lots around it.

For a while it worked, the dream clean and serene. Summer after summer the rich flocked to Lake Dreamland for fun and fresh air. The river breeze was a nice contrast to Louisville’s inner-city air quality, heavily polluted with clouds of particulates, all that coal heating homes, and automobiles on the rise. (This fact really drove the market. During the ’20s and ’30s, a ring of recreational resorts similar to Lake Dreamland popped up around Jefferson County, like Lake Louisvilla in Oldham County and Rose Island near Charlestown, Indiana.) Hartlage eventually converted the old dairy barn down Lake Dreamland Drive into Hartlage’s Barn, a lakeside country club. A place to play shuffleboard or buy a Coca-Cola.

Dreams come true until the nightmares settle in. Nightmare No. 1: The infamous 1937 Flood that wiped away prosperity, made the Great Depression even more depressing and drowned dream. Nightmare No. 2: No money or government help for Hartlage’s privately owned Lake Dreamland. Nightmare No. 3: Because the summer cottages were without many modern conveniences — public water, sewers, electricity and paved roads — nobody wanted to live there. Hartlage had to start leasing the land for next to nothing to low-income families. Nightmare No. 4: The poorly regulated, heavily polluting rubber-producing factories built to the north of Lake Dreamland during World War II. That area was and still is known as Rubbertown. Nightmare No. 5: The prevailing wind from southwest of Lake Dreamland, sending regular doses of nitric and sulfuric acids from the LG&E Cane Run plant.

How do you wake from the shake of the spook? You don’t. After Hartlage died in 1980, the county government bought the estate in ’88 for $100,000, with plans to improve the area, still primitive in its resources. The county sold lots to the residents for a measly buck — literally one dollar — but with stipulations. When and if the owner or family leaves or dies, the land would revert back to the county, to turn it into a “land trust.” Ray knows that doesn’t hold anymore. No one was gonna let that stand. Now individuals own their land and homes. Either way, Ray thinks the government got a good deal, and that it got its fair share in inflated property taxes. He built the house he’s in now 50 years ago, in a lot where he used to throw football as a kid, then just an empty field of grass. It’s on East Overbrook Drive, which is parallel to Overbrook West and across Lake Dreamland Road from Overbook Drive. Confusing, he agrees.

Used to be more people out here, some 120 families. Was nothing but houses on Overbrook Drive by what’s now Lake Dreamland Park, but the lakefront properties have regrown into forest, woody vines dangling from tree branches. People have either died off or moved on, vacant properties left to the Metro Government, real estate agencies or still in the name of whoever owned it. Most empty lots, on average .4 acres of land, assess for between $9,000 and $13,000, houses — most with one story and a couple bedrooms — for between $35,000 and $60,000. Riverfront homes can be worth $70,000. There are several empty houses in the neighborhood, including the one next door to Ray’s. Boarded up, but then broken into. Plywood nailed on, then gone. Rumor has it that some junkie kids stripped the place, like they strip most abandoned properties around here, taking whatever appliances were left behind, copper wires out of the walls. Some say the neighborhood has gotten bad because of the idiots that roam, the drugs that go around, the stealing. Someone stole tools out of Ray’s garage, but that was years ago. For Ray, the area is still pretty peaceful. Like a little piece of country. The woods, the most-of-the-time quiet, the lake up the road.

Ray remembers fishing in the lake as a kid. It was full of catfish, sunfish, crappie, perch, bluegill. He’d make a catch, then a fire, cook the fish right on the bank. In the summer, kids swam in the lake and in the winter skated across it. Hills slope on both sides of the lake, and one winter when a friend got a pair of skis, they took turns sliding down one side, across the frozen lake, then climbed up the other side, went back down again, like a pendulum. A teenager then, Ray knew which spots in the lake were waist-deep and that the “deep spot” was toward the Bramers Lane end of the water. Knew to wait for when the lake froze good enough to play on, unlike those two three-year-old boys who ran out without their mamas knowing, hit a thin spot and drowned. Ray remembers the sets of footprints in the snow leading right to the hole.

The lake was a lot nicer back then. Right now, it ain’t nothing. A “No Swimming” sign marks what once was from what is. It’s all dirty now. What you call it? A cesspool. Ray wouldn’t dip a toe in it. No telling what all’s in there. Seen from lake’s edge: a bunch of tires and a soggy couch. City won’t bring sewers this way because the neighborhood’s not in the 100-year flood plain and won’t provide aerobic septic tanks to treat the sewage before it pumps out. In the ’90s the Louisville Health Department estimated that those improvements would cost three-quarters of a million dollars — and what governmental department would spend that on poor old Lake Dreamland? Some around here are convinced sewage pits leak into the lake. It’s the smell. The thick film of algae coating the lake’s surface in the summer. Eutrophic, contaminated, undrinkable. All those ducks that used to cover the lake, some 200 of the damn things? Gone. Still, residents see the occasional crane or deer or fox by the water.

All the Rubbertown factories currently adjacent to Lake Dreamland — American Synthetic Rubber Co., Rohm and Haas Chemicals, DuPont Louisville Works Plant — no telling what kind of chemical cocktail is mixed. Some don’t believe the lake is polluted, but others say to survive down here, you gotta take a shot of the lake water or you’ll die; it’s the only antidote to withstand the cancer. People say if you eat a fish from the lake now, you’re likely to glow in the dark. There’s other talk by Dreamland residents. Talk of a car with a dead body in the lake, but that could just be some twisted folklore. Talk of a dead dog thrown in there. Pit bull shot in the head by the drug dealer who lives up Lake Dreamland Road, past the floodwall that separates the neighborhood in two — there’s a definite “this side” and “that side” — on toward the entrance of the neighborhood off Camp Ground Road.

Ray lights another smoke. It’s easy to wonder if his lungs are strawberries, the way he smokes these flavored Red Bucks. He’ll light one, then the next, lighter flicked on, then off, ember bright, then eventually stubbed out, like stars sped up in his dusky living room sky, alive then dead. Smoke lingers, shifts, settles into the wooden walls, adding layers to the must. The dust mimics, softly coats a framed photo of his four grown children — one son a golfer, one daughter working dental at the University of Louisville — a pocketbook calendar from 2012 with nothing recorded in it, a stack of Consumer Reports and Reader’s Digest. Ray doesn’t read much anymore, but he saw a Reader’s Digest article about Utah not long ago. That’s the one place he’d go if he could do it all over again. Utah’s got it all: deserts, mountains, lakes, rivers, valleys.

People start showing up at the Gospel Lighthouse Church across the street. The choir sings on Friday evenings. Ray can hear their hymnals in the summer. Close as he gets. At 6:15 p.m. a loud buzzing alarm pulses through the neighborhood. To an outsider, it may sound invasive, like a doomsday warning, but Ray knows that just means shift change over at one of the factories. Frances, his neighbor, rings Ray’s home phone, says she’s about to come by, drop off his dinner. She’s been bringing him dinner for as long as he can remember. Tonight, a fish sandwich. They look out for each other. She helped pull him out of alcoholism, all that vodka he hid on his breath. Ray loves Frances’ four-year-old son Jackson like his own grandson. Jackson calls Ray “Peepaw” and it keeps Ray alive.

Otherwise it’d be a lonely life. Ray’s wife died and he lives alone, just him and his two doggies. The overbite dog growls at Chub because he’s too close to her, and she was here first. Strange story about Chub. Was born right in this house. The mama, one of Frances’ boys’ dog, popped just the one pup out right on the bedroom floor. Same bedroom where Ray’s oldest son who used to live here died five years ago. Timmy was getting ready to feed the dogs, but then went to lie down and never got back up, dead on the bed. Coroner said it was a massive heart attack, all the blood vessels burst. Worst shock Ray ever had in his life. Timmy’d been on the phone with Mary, Frances’ daughter. Had Timmy said anything? Said he was feeling sick? Ray screamed and screamed for Frances, but she was out at the store, buying cigarettes. When she got there, he said, “Make him get up. Make him get up. He’ll listen to you.”

Ray is often forgetting things. If he doesn’t know you, he’ll repeatedly ask your name, where you’re from. He tells the same stories three or four or more times with minutes in between. Ray forgets. He doesn’t mean to forget. But some things Ray can’t forget, even if he wanted to. He wouldn’t even dream about them.

The Coca-Cola clock in the hutch stopped, no batteries. If it ticked, clock’s tiny click would clack against the glass bottles next to it, some big, some small, one found on the side of the road, one antique, stolen by a friend from a flea market. Everyone’s got a collection. Everyone’s got an obsession. This is Frances Ralph’s: Coca-Cola. The hutch is full of Coke’s red branding: cookie jars, tin lunch boxes, the Coca-Cola Christmas polar bears everywhere, plus a couple foreign cans her buddy who cleans planes got for her, ingredients in Japanese and German. There’s more stuff in the attic. Her husband Gerald says it’s all junk. Maybe he’s right, but whatever, that’s the drink in this house. It’s what Frances drinks during the day, all through the night. She knows they used to make Coca-Cola with cocaine. Apparently they don’t anymore, but she wonders why she grabs for it all the time.

Frances used to sprinkle cocaine in her coffee. A lady at work got her hooked when Frances worked at Dupont washing, drying and inspecting hazmat equipment, keeping the heavy neoprene suits ready in case of a spill. When a great flood of chemicals spilled in Rubbertown eight or nine years ago, Frances had just gotten home from the factory. She’d only been home long enough to get a shower and the smell off her when her boss called.

Hadn’t even been to the store to pick up cigarettes or nothing! But back she went for a Monday-to-Monday cleanup, the spill never ending, leaking into the river. Damn, was Frances tired. Of course she said OK to, “Here, let me give you a little something to bump you up....” Yes, she’s done her dirty, she admits it. But only after her six kids were grown. Only after they’d moved out. Frances quit when she realized she was pregnant with baby Jackson.

She couldn’t believe it at first. Forty-three and popping out a seventh kid. Another one? Twenty years after her last son was born? Now she’s 47 and Jackson’s four and the two are almost always together. They’ll go to the Dollar General daily, get Jackson some new LEGOS, surprise Easter goodies. Sometimes they’ll ride through downtown Louisville because Jackson loves it. They’ll listen to Janis Joplin’s “Mercedes Benz,” and Jackson will scream, “Oh, Lord!” He’s always hollering about something, full of energy, maybe because of the Coca-Cola. He screams things like, “WHOAAA-OOOOO-AAAAA!” and rolls his chunky body about on the floor. He’s the kind of kid who does what he wants to, listens when he wants to, runs for the neighbor’s pile of leaves even when Frances warns him not to, ’cause he’ll get all itchy, ’cause they’ll have to do breathing treatments. He’s got bad asthma. Frances keeps his inhaler on her, and Jackson yells, “Cannonball!”

Frances is in the kitchen, prepping supper. Chicken falls from the bone in a slow cooker for barbecue later. It feels like a cabin in here. The openness, the wood beams, the wood walls, the wood-burning stove, which they use all winter, way cheaper than paying for heat. Only problem is the dust it leaves and restocking the logs. Jackson just ate a nachos Lunchables and now he’s zoned in on the plush loveseat, watching Cartoon Network’s Uncle Grandpa on the big-screen TV, volume high. Sometimes he’ll get up, shorts caught on his chubby butt cheeks, and stand in the front doorway, push the door with the broken screen flap open and closed. He’ll put a big toe out and then back in. He’ll step out, let the door slam all the way behind him, and Frances will yell at him to get his ass back inside. He’ll waddle in screaming, “AHHH!!!” Raymond, her 26-year-old son who lives at home again because Mama begged him to, is quiet behind a laptop. He’s one of the good kids. Gerald is at Lucas’ Auto Shop, working on cars with Frances’ brother-in-law, Junior, who owns the place. Gerald’s worked there forever, and he works himself so tired that usually he comes home, eats supper and falls asleep in his recliner.

Frances is on disability and doesn’t work anymore. Thyroid cancer. And spots on her brain, so say the zillion MRIs. Brain doctor says it could be MS. Frances gets lost sometimes. Forgets where she is, who she is. Once she woke and the house she’s been living in for 29 years didn’t seem familiar. She didn’t recognize Jackson, not his chubby cheeks or thin-lipped smile or small squinty eyes, features that resemble her own. One afternoon when she took Ray some supper, she showed up at his doorstep, blank, confused. When he called her by name, she said, “Do you know me?” Now she can’t go down the street without a walkie-talkie. Most of the time she’s present, though. Sharp-tongued storytelling and cursing, smoking Marlboro menthols.

When it’s pretty outside, she and Jackson hang in the front yard, draw with chalk or play with the remote-controlled car. On the flagpole in the grass, Old Glory hangs tattered, torn. Red and white stripes fly different directions when the wind blows, and it makes one wonder about that old dream. Frances’ brother Bubby says the Ralphs need a new flag. Frances and Jackson play in their large yard where there’s a swing set and slide. She remembers when the clubhouse sat on the concrete foundation in the yard. Used to have some hellacious parties over there 20 years ago. Especially come Halloween, whew boy. Yard full, street covered, always cooking up something in the backyard — grilling ribs, bell peppers, onions, everything. When cops rolled up, Frances’ first thought would be, “Who’s smoking pot?” Of course it was old Eddie Brennenstuhl, who lived on the other side of the clubhouse, both gone now. That short, fat, ornery son of a bitch, always trying to see some titties. He thought he was ZZ Top with his big gray beard. Eddie was president of the Bluegrass Vanners, a big club among some Lake Dreamlanders. (And according to an old C-J article, he was the neighborhood association president for a stint too.) They’d make T-shirts in the clubhouse, till the health department tore it down, even after Gerald put new windows in it like they told him to, even after he added new siding. Next letter said there was asbestos in the tiles, and before Gerald could fix it, the clubhouse was gone.

Damn, does Frances miss the vanning days. Those were the good times, the three-day festivals, the “van-ins” or “van jams”. The closest one was in Beech Bend Park in Bowling Green, Kentucky, and as far away as Oklahoma. Very open, very free. Ain’t like you walk around naked or nothing, unless you’re painted. There was an old dude there who’d paint women’s bodies, make it look like they had shirts and pants on; flowers and mountains on their breasts. One year, the crew went to William, West Virginia, for a van-in. Frances and her older sister Karen Lucas drank Boone’s Farm wine, lay on the hill, watched the stars, so close it looked like you could reach out and touch ’em. Only rule at a van-in is this: If you pass out outside your van, you’re fair game. Nothing sexual or nothing, but they can duct-tape you, paint your nails, put lipstick on you, silly stuff. That night Frances and Karen fell asleep under the star blanket, woke up to Junior, Karen’s husband, sitting beside them, protecting them. “Told everybody y’all was awake and just watching the stars,” Junior said. Thank God. Frances wears her VW van shirt today — she wore it yesterday, and she’ll wear it tomorrow, too. She didn’t make this one but reps it proudly, saying, “If you ain’t a vanner, you ain’t shit.”

Sometimes she’ll take Jackson to the little Lake Dreamland Park playground up the road. It’s quiet during the day, till the kids are home from school and the basketball begins. She’s hesitant about the park lately, though, because of what you’re likely to find. Used needles in the mulch. All this heroin going around the neighborhood these days. Three overdoses since Thanksgiving, including the little sister of the guy who lives across the street. She overdosed in the back of his car, and he rode around and rode around and rode around, not knowing what to do with her. She was 29, left behind three kids. Frances thinks heroin is so bad because they got rid of those Opana pain pills. She don’t like it. Also don’t like what they’re showing on the news now. The needle-exchange program. How they’ll trade you clean needles for your old dirty ones, no questions asked. Maybe it stops spreading AIDS, but that’s just telling you to go on and do it. Just say, here you go. Hell no.

Maybe she’s bitter because of Andrew. Maybe she’s bitter because of James. They’re both her sons, 20-somethings. Frances won’t let either of them live here, but they stop by sometimes, usually wanting something: $10, or some cigarettes, or to crash on the couch for the night. She preaches at them till they run off, says doing drugs will put you one of two places: jail or the graveyard. When Andrew calls, says he wishes he was rich, Frances tells him if he had money he’d overdose and wouldn’t be rich anymore. James is supposed to be in a halfway house on Algonquin Parkway, where for three months he was clean and serene, but his ass hopped the fence last month. Why can’t these boys be more like Mary? Mary who’s clean. Mary who’s a nurse at Kindred Hospital overnight, student by day. Mary who’s got it together.

One afternoon when James calls, Frances’ end of the line goes like this: “They thought the cops got you on Cane Run Road. Donnie just called Andrew and told him that. I just seen you go out a while ago. You wasn’t in the truck with Crystal? Well, someone who look just like you slid down the seat like you was hiding. . . . No, I ain’t trying to make you feel bad. Well, Andrew didn’t run from no place either. And he isn’t here all the time.”

Frances’ phone rings a lot. It’s either Gerald on his way home or one of the boys, or Mary, or Ray, or Karen — also a neighbor — wanting to know what she’s cooking her to pack for lunch tomorrow. The phone rings and rings and rings. There’s one call she knows is bound to happen. She feels like it’ll come any day now. It’s morbid, but she waits for that call, the death report.

The clock is still silent in the kitchen.

Karen Lucas’ place on Lake Dreamland Road is like a bird’s nest, and family flies in and out of the perch with regularity. The perch is the porch in spring, the backyard in summer — everybody splashing in the above-ground pool, projector screen set up, movies playing against the house — and when it’s cold, the open living room in the house where she’s lived for 39 years. Karen never really knows who’s going to pop by next. If it’s after school, her granddaughter Bella will walk over from next door, with Lincoln following, then Braden, all in Mill Creek Elementary Leadership Academy shirts. Amazing how quiet skinny Braden is compared with the always-arguing twins. He’ll play tablet games on the porch swing, so silent you forget he’s there. Karen thinks he’ll be the next Stephen King.

Karen doesn’t know when Stinker will pull in the wide parking lot in front of the garage with Jack Jack in the car, but when she does, Karen screams to her little nephew, “Come give Boo Boo kisses!” If it takes some convincing, “I got candy for you!” Lil’ Chunk Chunk is sure to come running then. Stinker is Frances. Jack Jack is Jackson. The family’s got messed up nicknames. Stinker, Bones, Jaws, Fatty, Peanut, Pooter. Pooter is really Joseph, one of Karen’s sons. One of Karen’s girlfriends nicknamed him that forever ago, after a dog named Pooter, and it stuck, simple as that. He lives next door with his girlfriend, Emily, and their three kids. Karen got away without a nickname. Well, “Boo Boo” now because of Jackson.

The nicknames become a web, dot-to-dotting who lives where in the neighborhood, most of the family still here. Family is a big reason people stay around Lake Dreamland. It’s not rare to have cousins down the street, a son as a neighbor. Repeated names around here: the Georges, the Roeders, the Brennenstuhls, the Maddoxes. Karen’s mom, who lives on Overbrook West, must have 55 grandkids. Let’s see, Karen’s brother’s got 11, and Karen’s got two sons, so that’s 13. Her sister after her had four, which makes 17. Brother after that had two, so 19. Sister after him had three, so that’s 22. Sister Della had four, that’s 26. Frank’s got one, 27. Bubby’s got four, that’s 31. Brenda’s got three, that’s 34. Stinker’s got seven, that’s 41. Getting up there, see.

Granny lived next door until she died. Karen loved Granny, always fancy, prim, proper. Karen remembers the ice storm in 2009, when the power went out and how half the neighbors were over soaking in the heat from the fireplace and the light from the generator, how Granny next door was stuck without. Granny must have been 88 or 89 at the time. Karen was sure Granny would fall and break a hip, and told the boys to go get her. It was nothing but ice out — beautiful but dangerous, trees snapping. Granny answered the door, said, “Well, I gotta do my hair.” Pooter and his brother Kenny grabbed her, got her out of there.

t’s a Saturday afternoon and the songbirds sing and squawk loudly with their gossip and conversation. Inside, the TV is still on after the UK men’s basketball team’s Sweet Sixteen game, Karen high on a Wildcats win. She’s a Kentucky girl, through and through. Those are her boys, you know what she’s saying? Always loved ’em, even since they were the underdogs. Loved ’em because they were underdogs. Karen constantly wears UK T-shirts on her stout upper body. On her finger, a ring a lady at work gave her. It looks sapphire blue, but no, no, that’s Kentucky blue. Matches the UK charm on her necklace, the Wildcats bangle on her wrist, only three bucks at the Dollar General. She’s had it on for years. Karen’s recently been decorating wooden K’s, in blue with a bow on top.

It’s sunny today, finally starting to feel like spring. Wind chimes line the top of the porch and softly ding against each other. Junior and Dave, who lives in the remodeled house across the street, try to install new glass double doors, old set already off, but Home Depot gave them the wrong size, and the damn things don’t fit. The drill screams its shrill scream, and then stops, and the two men mumble, working together to solve this problem. Junior is mostly quiet while Karen talks to everybody. He looks at the clock, says it’s damn near margarita time, which is code for Jack Daniel’s.

Karen’s grandson J.T., who has lived with her for a while because he doesn’t want to live with Pooter, grabs Karen’s Marlboro menthols out of the house for her. J.T. goes to Western High School, like the rest of the family did, most maxing out with a high school diploma, if that. J.T. hates that school, too strict. Sneeze and you’re in trouble. He’s got a broken arm in a cast, but he still plays basketball down at the park, if he’s not grounded. He hands the pack to Karen, and she uses Emily’s ember to spark her smoke. Karen’s niece Misty Roeder is here, and she’s brought along her two girls, who just won their soccer game. Karen’s so proud, asks for hugs and kisses. Karen lives for the love. They go off with Bella to the trampoline to make rubber-band bracelets, the craze these days.

“Did you like that game!” Karen asks, clap, clap, clapping and doing a little shoulder dance. “Thirty-six and OH! OH! OH! Looked like it was gonna be ugly at the beginning, but they settled down, and rode on. Ride the waves, bay-bay!”

She laughs at her own mad sayings. Then she tells the group how last year J.T. cried after every game the Cats advanced.

“I only cried once. One game,” J.T. says. He’s 15, with that pride that can’t be touched. Fifteen and thinks he’s

in love, his little girlfriend sometimes over sitting on the porch swing with him, flirting that he’s fat even though he’s fit.

“Nuh uh, you cried a couple times when they won,” Karen says. “If they win the championship, shiiiiit!”

“Oscar said if they win the championship, he’s gonna buy him a new house. I said, ‘Why? ’Cause you’re gonna set the old one on fire?’”

Karen knows she’ll have to ask off work if Kentucky is in the final game. The game starts late, and Karen gets up early, 3 or 3:30 a.m. to be at the Louisville VA Medical Center on time. She’s been there 26 years, sterilizing equipment before surgery. She can’t wait to retire, so she can craft more, get back into scrapbooking.

Pooter walks over from his house with some jelly beans and a banana-nut muffin. J.T. asks for half.

“I pulled a tooth out a couple months back, then my other tooth broke,” Pooter says. “I think I got a nerve hanging out.”

“Why don’t you sign up for Passport [the health plan]? Now’s the time,” Karen says.

“He’s got gum disease,” Emily says. She wears glasses and has a thick teal streak that pops from the rest of her dyed-dark hair. She’s always changing it.

“Probably the same thing your Uncle Tom got. Had to get all his teeth pulled. Now he’s got false teeth,” Karen says.

“If I could get it to stop burning long enough, I’d get the nerve out myself,” Pooter says.

“You need that lidocaine,” Karen says.

Emily looks at Misty, asks, “You getting everything ready? For your wedding?”

“Oh, Lord,” Misty sighs.

“Where’s it at again?” Karen asks. She and Junior got married up the road, at what was once Lake Dreamland Baptist Church, the reception on this very porch, with some bands set up, and a bouncy for the kids.

“MillaNova Winery,” Misty says.

“Is it open bar?” Pooter asks.

“If you’ve got money, it’s going to be open,” Karen says. “Ain’t it Fourth of July day?”

“Yep.”

“Girl, you messed up my Memorial Day weekend when you graduated out of the 12th grade 100 years ago. Now you’re getting married on the Fourth of July,” Karen says. “Well, I’ve had someone screw up my Fourth of July two years in a row.”

Emily’s quick: “I was gonna say, Misty. She will never let that down.”

“NEVER!”

“Once you get married, it will always be you screwed up one of her Fourth of Julys.”

“Right,” Karen says. “Good thing I got vacation scheduled that week.”

“I still have to hear it, and that was eight years ago,” Emily says.

“What was it?” Misty asks. “Your kids? You had your kids?”

“Mmhmm,” Emily says.

“Damn you, Emily!” Misty jokes.

“Right?”

“Them little brats could’ve waited!”

“I wanted the twins out!”

Karen chimes back in: “That’s where we spent our Fourth of July was at the hospital. The whole evening. We didn’t get no fireworks.”

“Well, we made our own fireworks,” Pooter says.

A little freckle-faced boy rides up on his bike, asks for some quarters, please. Karen takes his dollar, goes inside to get some change. By the Lucas’ garage is an old Pepsi machine a friend who worked for the company gave them years and years ago. Karen thought she’d make bank on it, but she doesn’t, probably because she only charges 50 cents a can. Everybody this side of the floodwall uses it. “Osama Bin Laden,” as J.T. calls him, because of the long-bearded resemblance, uses it. Destiny from across the street uses it. Karen jokes with the teenage girl, even though Karen’s got a real disrespect for the house where Destiny came from. Says all of them are on disability checks, food stamps, 16 of them living in the house, which is falling apart, holes in the walls and floors. Good for nothing. Neighbors even put up a huge spray-painted sign — “LIKE A GOOD NEIGHBOR, STAY OVER THERE” — after they threw hot dogs and plumber’s glue in their pool. When people think of Lake Dreamland, if they even know what the hell it is, Karen worries they think of things like this, and only this.

It’s Pooter’s day off and he’s working on the four-wheeler. The pontoon is stripped to its frame in his parents’ garage. Seems like everything is always in a state of repair for the disrepair. The country hurting because of Obama. There’s a camera on the garage that looks down at the pavement. Is it on? If he tells you that, he’d have to throw you in the lake.

Pooter’s got a Glock clipped to his belt. Does he always carry his gun? Do fat girls like cheeseburgers? Not but an hour ago, some short-ass high-ass in a big Marlboro jacket tried to sell Pooter a safety plunger for the gun. Could barely understand anything he’d said except the words “five dollars.” What the hell would Pooter want that for? All that’s gonna do is get in the way of shooting one of y’all. Just gives somebody a few more minutes to get you. One can see the same dude standing at the edge of Lake Dreamland Road on a Saturday afternoon, smoking a cigarette, looking lost as hell, looking nowhere.

Five Finger Death Punch plays as Pooter cranks the four-wheeler’s insides. He admires this band because they support the military. Half their profits to the Wounded Warrior Project, and they toured in Afghanistan for the troops. Everybody’s got a calling, and Pooter thinks his was to be in the military. “A recruiter ain’t nothing but a car salesman,” his friends told him. “You tell him what you want.” That’s just what Pooter did. Said he wanted to be in the infantry, or be a Marine Corps scout sniper. Said he didn’t give a darn if he lived or died. They pulled a psych test on him, and he got denied. Wouldn’t tell him details because he cussed them out. His mouth wrote a check his ass couldn’t cash. Now all he’s got as far as that dream is some military posts on Facebook and a dog named Soldier.

There’s only one way in and one way out of Lake Dreamland, so any stranger to it is immediately noticed. Considered with caution. Sometimes assumed a cop. In effect, you hear one thing, you hear another. There’s hyperbole, lies. It’s complicated, layered, hard to pin down. Like a dream that shoves you through many doors and moves you through many corridors. Oftentimes it seems dreams don’t want to be understood, or analyzed. That’s why they’re so strange, why we’re always forgetting them, letting them go.

Fire in the club lot. Someone must’ve had a late-night shenanigan, debris left from who knows when, the black ruins turned to thin ash with touch. Lot is clear anyway, no worries, nothing natural to burn except sticks, mud and memory. The clearing sits at the end of Lake Dreamland Road, perpendicular to River Front Drive, quiet beside the lake. A lone goose swims the waters but shakes his head uncomfortably. Another goose follows, stretching its neck as if with effort to catch up. They leave ripples that glitter in the sun until they disappear.

Gary Huff remembers how, in 1957, Club El Rancho, the lakeside country club turned tavern and dance hall, pumped out rock ’n’ roll. Gary’s dad played lead guitar in a band there. He can’t remember the band’s name but remembers the ridiculous matching vests his mom made for them. They’d play weekends and New Year’s Eve inside the clubhouse, or on the big bandstand stage once it was built. The neighborhood could hear the big bands from the porch. Gary and his brother and Jerry Burke snuck in there, saw a girl onstage with tassels on her breasts, flipping them around. Can’t forget that. A little boy’s dream.

Gary remembers when the El Rancho burned, burned, burned in 1967, after the Louisville Outlaws, a motorcycle gang, had moved into the club. Some think a Lake Dreamland resident torched the place to get rid of the nuisance, the vrooms of some 50 motorcycles. Windows open in the summer, no AC, the motorcycles could wake a kid up at three in the morning, scared. But no, Gary saw who did it. The FBI guy. The cop. Saw him run with two little gas cans, man. Ran behind the building, lit the son of a bitch, then was gone. Twenty or 30 minutes later and BOOM! Burnt up 62 motorcycles in there, boy. Could still see the metal frames on the bikes.

Gary’s been in the same house on River Front Drive since he was born. He’s 55 now. Don’t reckon he’ll move unless he meets a rich girl with a house somewhere. His square house sits beyond the road’s curve, past Ed Hartlage’s old riverfront home, the biggest house in Lake Dreamland, with two acres, assessed at $120,000. Old Miss Betty Burton used to live next to him till she moved across the street. Now her daughter, Missy, lives in that spot with her husband, Ed Lanham, married last fall in Missy’s mama’s front yard.

They drink beer together in the driveway on warm days after work. Gary, cans of Bud Light. Ed and Missy, Coors Light. Gary jokes they’re the only ones in the neighborhood with a J-O-B. They talk about perusing Walmart, about Gary’s dead dog, how German Shepherds are as smart as seven-year-old kids, and better than any alarm system on your house. Ed thinks he may grill out tomorrow, the weather the way it is. Can’t wait for summer to reap what he sows: beans, onions, zucchinis, carrots. Vegetables, vegetables, vegetables, so many he gives them to the neighbors.

Today they try to figure out when the next flood will hit. Gary says, well, you had you the 1937 Flood, the ’64 Flood, the ’97 Flood. He was here for that last one. Rough. Full sheds going down the river. Couldn’t see the guardrails near the lake, past the basketball court. If you had a truck, you could kind of get out. Just had to know where the road is cause you could go off into a ditch. Anyway, Gary recognizes a pattern. A flood just about every 25 years.

“So when we get the next one?” Ed asks.

“Just figured it up the other day. Next is in 2023. Gonna happen, buddy. Just like clockwork. Better get you a damn boat!” Gary says.

“I got a boat and a canoe, OK?” Ed says.

“Not in the backyard, you don’t! You’re gonna need it over here! You’re gonna get drunk and pass out and there will be water all around you.”

“I’ll let the water rise up, and the boat will come off the trailer itself.”

“Well, make sure you come over and check on me.”

Miss Betty wakes early, drinks her coffee. When it’s warm, she’ll sit out back and watch the empty barges go down the river to LG&E. Cars zip up and down Indiana State Road 111, across the river, parallel to her yard with the 20 feral cats that come and go. She feeds them twice a day, and has names for all of them: Daisy, May May, Lulu, Tiny. Betty feeds the birds too. She’s already had Baltimore orioles this year. Bet she had 25 cardinals back here in the snow, red beautiful against the white. Betty calls Lake Dreamland “God’s little forgotten land,” but this seemed next to heaven, so peaceful.

She’s lived on River Front Drive for 58 years, alone now, one daughter in Arizona, the other across the street, most the rest of the family dead. Lost her husband, son, mother, father, sisters, brothers. Betty’s the youngest, now 77, the last. If they’d been alive for Easter yesterday, they would’ve all been down at Betty’s outspoken mama’s house, like sardines packed in at holidays. Never a one they’d miss.

Betty knows family, loves family, misses family, feels like people don’t understand family anymore. People don’t care where their children are. Little kids run around the neighborhood at midnight. When the neighbor’s kids play in her roundabout driveway, she’ll sometimes shoo them off. Not gonna get hurt on her property. She remembers when that little girl from the “Be a good neighbor, stay over there” house was walking logs past the riverbank behind Betty’s house and fell in that cold February river. If Betty hadn’t heard the dog, she would have never known the girl was wailing at the base of the slope.

When Betty’s kids would come home from school, they changed, did their homework. As soon as their daddy came home, they ate supper together, cleaned up the dishes, then they were allowed to go outside, play baseball in the red cinder road with the 25 or so other kids out there until dark, then in the house they came, got their baths, watched TV for an hour, then bed, with a hot breakfast waiting for them the next morning. Didn’t have much money, but they worked, made it work. Don’t see that anymore. Not many places anyway, especially not on Lake Dreamland Drive this side of the floodwall. It’s gone to the dogs. Only time Betty’s driven down that road lately is when they had the road blocked because a water line busted. Those people need to watch The Waltons.

Her garden is in straight lines: the coneflowers, chrysanthemums, lavender and the stonecrop she calls “neverdies.” Fake frogs and mosaic lights sit among them. The little white bush of hair atop her head is at the longest it’s been in 20 years and she can’t stand it. Got a hair appointment tomorrow. She’s never been one to let her hair hang, always had to have it just in place. The grass is cut and there’s not a single bit of litter in the yard. She hopes tomorrow isn’t windy so she can put grass seed out.

Betty’s tired of defending where she lives. Lake Dreamland gets a bad name. Even worse now with that Southeast — Baptist? No, Christian — church paper. The church spoke to one of the worst druggies out here, and the article featured the most run-down sections of the neighborhood. And did you see the video from WHAS-11? Talking about the Dream House, the new education-meets-ministry mission by Southwest Church pastor Tim Hartlage, great-grandson to Ed Hartlage, who dreamed Lake Dreamland. Betty called the news station and complained about that. Tim Hartlage, who grew up in Lake Dreamland, says, “It reminds me of the Appalachian regions in eastern Kentucky. The difference is, it’s so close to society.” Councilwoman Jessica Green, whose district includes Lake Dreamland, says, “If you ride through it, it’s like a third-world country. You turn off certain streets, you wonder if you’re still in the city of Louisville.”

To be fair, the Dream House, a renovated residence on Lake Dreamland Drive on the other side of the floodwall, is an effort to lead folks, specifically through tutoring kids, away from the poverty Betty doesn’t want to be associated with. “Education is the thing in our country that’s gonna pull people out of poverty,” Tim Hartlage says. “If they can’t have a job, can’t make a living, they’re gonna end up on some kind of welfare, like a lot of people down here.” Lake Dreamland might be on God’s radar.

The garbage truck goes by, and four loose dogs chase it, barking, howling. The dogs aren’t hers. They think they belong to her, but they don’t. They belong next door, but they keep escaping their flimsy pen. The dogs jump on Betty when she steps on her porch, crowd her as she walks down her driveway. They know her because she’s been feeding them since they were born, a pile of dog food on the side of her house. She says they need to be fixed to keep from having more.

Neighbor Fred has the red pickup in the yard. The bed faces the river and is full of dirt. The

sky gray, with a threat of rain, he works quick to dump it on the ground. His wife Mariam wants a pond out front, so they gotta move the dirt from there somewhere else. She gets what she wants. Women. Harley, Fred’s working buddy, sits on the side of the truck. Fred pulls up his dirty pant leg to reveal a big ol’ arthritic ball on his knee.

Betty marches up to the men, her stature short and hunched, points at the dirty pen, says, “Fred, we don’t need no more babies.”

“Oh, here we go,” Fred says. He’s heard this rant before.

“You know you got two now you need to watch.”

“I told Mariam she needs to get them fixed, then throw them back.”

“Get the girls fixed, leave the boys alone. This one’s already been in heat once, Fred. Poor old Butch like to drove himself crazy.”

“Down there where I play bingo in Radcliff, you can get the dogs fixed for free.”

“Well, why don’t you do it, Fred?”

“I don’t like driving that dog around. I took her to get rabies shots and she had a tick about that big,” he says, holding his thumb and index finger a good inch apart.

“Get you a carrier, put her in the back of the truck,” Betty says.

A few days later, an argument in the driveway. Betty’s out by her fence and Mariam walks up, mad that Betty has been feeding the dogs.

“Miss Betty, why you lying to my face?” Mariam says.

“All winter long, I was out there feeding them when nobody else was,” Betty says, pointing to the pen.

“I got a 50-pound bag of dog food,” says Mariam, talking over Betty. “You think I eat it?”

“Fred don’t put no shelter up...”

“I don’t want to disrepect my elders, Miss Betty...”

“Old or nothing...”

“I’m done with you, Miss Betty. Don’t come on my property, feed my dogs...”

“Mariam, they have to be fed every day....”

“You be fronting, Miss Betty. Front-ing.”

Hearing the fuss, Missy and Ed, beer in hand, cross the road. Missy stands silent, while Ed says, “She’s did more for those dogs than you ever did!” He knows how Betty treats them like children. How worried she was when they disappeared for two days. ’Bout had a heart attack over some mutts.

Despite Fred’s sighing and eye-rolling, Mariam makes Fred drag out a 50-pound bag of dog food to prove that they’re fed. Betty is out from behind her fence now, and the ladies are closer now, proving points with their hands, and it feels like someone’s going to hit someone. Eventually Mariam just says, “I’m done with you, Miss Betty.”

Miss Betty says OK and throws up her hands.

Paul Bramer has his white dog Snowball tied up by an electrical wire. Paul throws him an old pork chop, then steps toward his blue truck. He bought this truck when he was drunk. Wrecked it the first night he had it, hit a curb the size of his porch, tall and concrete.

The truck’s still holding up, despite the several scratches he’s put on the thing. Did all that out junking. He’ll go out to Valley Station or Pleasure Ridge Park, anywhere looking for anything. You can find anything on the side of the road. Stoves, refrigerators. Paul tried to put a car on here once. Tried to put some bent-up, run-over metal banisters from Cardinal Stadium on here once, but that got his big white bearded face in Crime Times Mug Mag for stealing. He hands out that November issue like candy.

What we got in the truck today? Got an old busted-up TV. A bike spoke. An electrical box. Some documents from the governor or something like that. His buddy Joey told him to hold on to those, that they might be worth some money. Paul sells the stuff he gets at the flea market on Seventh Street Road. He pulls out a civics book you’d give an eighth-grader, but Paul can’t read, or spell too well. A-N-D, of course, but he can’t write a letter or nothing like that. Tried to several times in jail but always ended getting some dude to do it for him. Paid him lunch. Used the same tactic in high school. Went to 11th grade and came out the same way.

He sits out front of his house on Lake Dreamland Drive, on the futon covered by a bright blue tarp to protect it from the rain. Paul drinks him a cold beer. Always. Has two out here now, one open in his hand, another by the futon leg. He forgot what he did with his first beer, thought he drank it, so he got the second. Usually he cracks his Busch open at 11 a.m., but first thing was first today: Court. Drinking-and-driving charge from 10 months ago. He’s been trying to straighten up, not drive while he’s drinking. He scratches at his beard. People call him Father Time. Santa Claus. Si, from Duck Dynasty. He’d like to be like that. Like to have money. He’s so broke he can’t even afford to pay attention. He lives on junk earnings and disability checks for his heart (six bypasses on the old ticker).

Paul looks like a mis-buttoned camo king on his throne, manning the yard, waiting for Jay to call or a friend to stop by. Lot of people in Lake Dreamland don’t care how they run their yard, but this lady in the nice white house across from Paul keeps calling on his ass. Sics the health department on him. He’s on the top of the complaint list, soon to get fined. The Newmans, the old couple next door to that hag, recently moved. The wife got dementia, haunted by her daughter’s sudden death in the house. They left haunted Lake Dreamland, drove south on I-65 toward Rough River. That’s where everyone who wants to leave the neighborhood wants to move. The new dream place, the new dream.

In the yard, a bird bath but no birds. An angel figurine buried under gravel. His dead brother Jamie turned tires into flowerpots, nothing but dirt in them. There’s the dead burning bush. When Jamie died, it died. That was his bush. Paul accidentally sprayed too much weed killer near it, thinks that’s what got the big old “heaven leaves.” The burning bush finally burned. Paul’s other brother, Alby, lives in the garage next to the house. He’s 70 — 14 years older than Paul — and

used to be on night watch at El Rancho. Paul forgets about him in there. Only sign of life the sounds of an action movie buzzing through the plastic-covered window, AC jutting out its bottom with a small wheel and real chicken foot resting on it.

Paul’s wife is inside sleeping on the couch again. She’s always sleeping late. It’s 2 p.m.! When he looks to the right of him he sees the entrance of the neighborhood, can see the Lake Dreamload Road and Old Camp Ground Road signs bright green, perpendicular. He can see that school bus that recently arrived out of nowhere. It’s no longer yellow, but gray and black, like it’s been burned, windows cracked and busted, eerie. When he looks left, he sees his longtime neighbor Rick Blair on the porch, binoculars glued to his eyes, glued to the tree across the street. His little Chihuahua Ruby, or RuRu, stands beside him.

Rick’s e-cigarette hangs around his neck, its boxy battery resting on the bulge of his belly. On his head, a Lake Dreamland Fire Department beanie. Rick volunteered for the fire department for 36 years, just about as long as he’s been on Lake Dreamland Drive. Went into the Rubbertown plants all the time, sometimes there for two or three days after a spill. Dealt with house fires and car fires, too. Back in the day, it was like tradition to volunteer for the LDFD. Not as many volunteers these days at the station on Cane Run Road, or the one near the neighborhood’s entrance, a somewhat iconic symbol, like an official “Welcome to Lake Dreamland.”

“What ya looking at, Rick?” Paul yells.

“There’s a hawk’s nest up there,” Rick yells.

“It got babies in it?”

“I’m making sure it don’t come down.”

Paul laughs because Rick really thinks that bird is going to get his little dog.

Rick continues to hawk the hawk’s nest. Rick knows old Father Time is living here on a prayer. That the house doesn’t belong to Paul but to the dead-now Donoways, who took Paul in and raised him as a kid. That there’s no blood relation. Donoways didn’t even keep him around that long, once they couldn’t handle him anymore. Too wild. Buck wild. Eventually they sent him back to the Bramer world.

Bramer is a big name around these parts, like Hartlage. Gotta know the Bramers, the family that once owned land around here. Down Camp Ground Road, a lot with rows of cranes, “Bramer” tattooed to their booms. Bramer Construction Co. wanted nothing to do with Paul, though. He was one of the young group of Bramers. Born to a mama who was so drunk during labor she didn’t need a sedative or nothing, just popped Paul out in the backseat of the ’49 Chevy.

Paul is proud of the name. Bramer. Bramers are tough, got a good breed. They call ’em bulls. Paul still feels tough. Tries to whoop people all the time. Had this one girlfriend believing he could whoop the world. He went with her for seven years. He’ll fight any old punk. Sometimes his cousin when they’re drunk. Once old Gary Huff down on River Front Drive took a bat to Paul’s head. He’s still got the dent, the scar.

Photography by Mickie Winters.