As his Death Clock ticks, 21c's Steve Wilson cannot stop.

Photos by Chris Witzke

This story originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of Louisville Magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Every party has its beginning and its end and tonight’s is just beginning — sparks fly and fade. Louisville Executive Aviation burns hot despite the February evening chill. Hot with Harleys and drinking and flannel and youth. It’s February 7, 2013 — Steve Wilson’s 65th birthday, and damned if he doesn’t know how to throw a banger. The hangar has been turned into a “truck stop,” gritty, rural as his roots. Wilson rolls in around 30 minutes after kickoff, balanced on the back of a motorcycle, his smile proud as the bike’s vroom.

Wilson’s quiet, keep-it-slow wife Laura Lee Brown (tiara of the billions-in-bourbon Brown-Forman Co.) rocks a leather jacket and glittery silver pants. Wilson’s longtime personal aide invited the motorcycle club. The interior designer of Wilson’s farmhouse mansion wears a wig, mullet curls pouring over his shoulders. The performance artist who lived in Proof’s restaurant window for a month poses for a Voice-Tribune picture. The man filming the party focuses his camera on a splash of bourbon swallowing rocks; on the birthday cake with two small 21c penguins on top, almost in a red kiss; on the dancing — a young gent whips his blond hair back and forth, topless in his short-shorts. Mayor Fischer smiley as ever.

The night twists and turns with performances from Wilson’s deep Rolodex of entertainers. A man dressed as a woman, a woman popping out of a balloon. A woman in a metallic pin-up suit presses an angle grinder to her silver-clad belly. Sparks. It’s just like the circus Wilson always wanted — the magic he saw one summer back home in Wickliffe that kept him in awe. The smell of the elephants, the revelation of live music, the aerialists suspended. A tent transformed the boring baseball field into something he could understand. “I wanted to run off with the circus,” Wilson says.

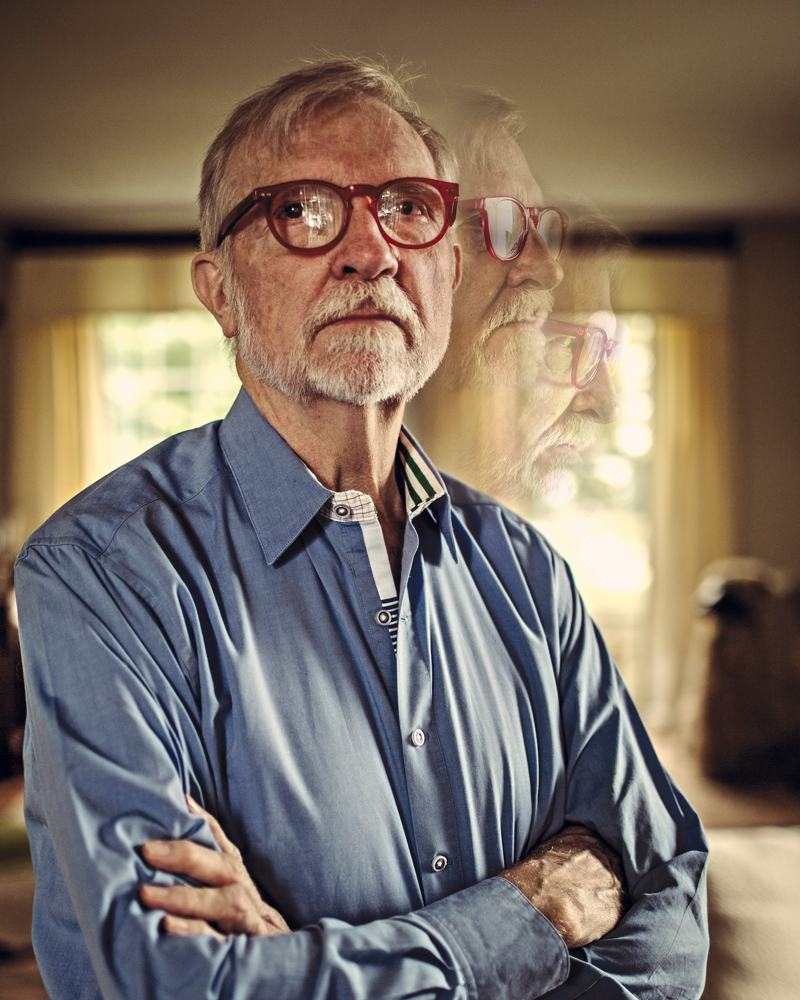

Wilson dances alone on the stage. He wears a black cowboy shirt with lucky horseshoes stitched on the shoulders. He clap-steps in the red glow. It’s as if there’s no old bone in his body except the one that remembers how to groove. His brown eyes are the same as the boy’s in the black-and-white portrait on display. Only now, no overalls. A gray beard hugs his square face.

In the middle of all this madness, a tattoo artist inks the middle of Wilson’s forearm. He winces a little, but not much, because he’s buzzed. Black outlines green — a four-leaf clover. “Lucky to be alive,” Wilson says. Back onstage, he holds his new permanence up to cheers and looks like the luckiest man in the world. Like there is all the time in the world.

The “Death Clock,” as Wilson calls it, ticks onstage, the red numbers constantly moving toward what is less than them, and what is less than them is life. If the clock is right, Steve Wilson has 16 years, zero months, six days, zero hours, 26 minutes and 47 seconds left to live.

*

The Death Clock is Austrian artist Werner Reiterer’s “My Predicted Lifetime.” The piece looks like a large alarm clock — a black, bulky box with LED-red digital numbers — but instead of time to wake up, it’s time never to wake up again. A countdown to death, down to the seconds, ticking down, down, down. The artist based Wilson’s predicted time of death on an actuary test, an assessment insurance companies use to determine risk factor, with questions like: Do you smoke? (Wilson, now 68, says: “Never. Occasionally a cigar.”) Do you drink? (“Bourbon, yes.”) Have sex? (Chuckle. “And it even asks how often.”) The oblong death dinger is mounted outside Wilson’s office, the corporate headquarters of 21c Museum Hotels, two doors down from the boutique hotel’s flagship site in downtown Louisville.

Born in 2006, 21c is the child prodigy of Wilson and Brown. It is a place to sleep with art or just wander some free five a.m. (the museum is open 24/7, always gratis) and marvel at the mind maps on the walls, or clink drinks and forks at Proof on Main, the upscale restaurant inside the hotel. Originally an experiment with the goal to share the couple’s growing art collection, help reinvigorate the city center, conserve historic space and defy suburban sprawl, the 90-room hotel on Main Street (in buildings that were once bourbon and tobacco warehouses) is booming. “Art is so often dismissed as less important,” Wilson says. “That it can be the anchor of economic development, establishing jobs for so many people — it’s a whole series of rewards. Sort of like a pebble in a pond. The ripple effect.”

The 21c ripples are ever widening into other “second-tier” cities with downtowns needing revitalization: Bentonville, Ark.; Cincinnati; Durham, N.C.; Lexington; and, as of June, Oklahoma City. “I never expected it to be such a big enterprise, to have people identify with it so strongly,” Wilson says. Each 21c has its own upscale, locally sourced restaurant and its own 21c penguin — plastic tall-as-teens birds that have become accidental 21c mascots (visitors love to pose with them for photos). An Italian art group made Louisville’s red penguin, the original, and now green, yellow, fuchsia, blue and purple ones in the other cities. Wilson says, “What started as just a hobby or pleasure has turned into significant . . . weight. I’m not complaining about that. It’s a constant reminder. Like my clock.”

Now 21c has more than 60,000 square feet of exhibition space to fill with socially, racially or sexually charged art. Here, art is not decoration — it is focus. It can be jarring. It is always changing. You’ll never see a Monet or Cézanne. Instead, you’ll find today’s emerging artists — 21c: 21st century. Currently on display in 21c Louisville’s atrium is the anniversary exhibition “21c at 10: A Global Gathering.” A bright-pink tapestry dominates one of the walls like a matador lady’s cape, with sewn-in images of birds, volcanoes, a decapitated doll — the artist’s ex-boyfriend, which Wilson points out to everyone. Alluring photographs of nude men hang nearby.

Four sculptures of naked children stand behind the reception desk. On display in the lobby: miniature reliquaries and churches made out of ammunition — a shot to the temple. On the sidewalk outside 21c stands a gleaming gold “David,” two times bigger than the original, looking rather cellulite-y from layer after layer of the 3-D printing that produced the three-ton statue. The first week “David” was on display, an incensed woman wrote a letter saying she would never be able to bring her 12-year-old daughter downtown again.

Some art isn’t supposed to be easy to look at.

Like the Death Clock.

*

Wilson knows people at the office don’t like his Death Clock. Especially after he persuaded the artist to shave off some years. Wilson wanted was a more “realistic” date of demise. Call that tempting fate, controlling the uncontrollable. On April 21, 2016, Wilson’s altered Death Clock shows 11 years, nine months, 23 days, five hours, 34 minutes and three seconds. Eleven years better than 11 months, but still others shudder. Why be constantly reminded of that particular truth? “You embrace it or you avoid thinking about it,” Wilson says. “I’m not looking at it, like, ‘How many more minutes have passed away?’” He’ll walk under it, glance up, remember the ultimate message — he has limited time to get everything in order. A letterpressed sign parallel to his office door reads: “Imagine on your deathbed you are able to see two films / One highlights your achievements / The second shows what you could have achieved with your ability, talent, opportunity....”

Details make him tick and wasting time ticks him off. “I like to be decisive,” he says. “Move on.” There is project after project, deadline after deadline. There’s 21c’s expansion — Kansas City, Nashville and Indianapolis locations are currently in the works. There’s Woodland Farm, the 1,000 acres in Oldham County, 30 miles from downtown, where Wilson and Brown live among roaming bison and hogs and sustainable agriculture. There’s Hermitage, an historic Oldham County equine center. “Nothing is ever completed,” Wilson says. “There’s always 10 things going on at once.”

No time for dead space. He can’t even relax on vacation. Makes him uncomfortable. Ten days away and he’s already thinking about what he’s missing at work. Thank goodness for the internet. “I can be in London or South Africa or Venice and still review drawings, have conference calls,” he says. Vacation for him is studying hotel rooms, paying attention to the texture of the robes, the way the bed is made, how the room service works or doesn’t. He’s checked into hotels and checked out immediately because he didn’t like a room or the personnel’s unhelpful attitude. He chuckles. “Laura Lee always asks, ‘Is it OK to unpack now?’”

Wilson, the king of aesthetics, absorbs design. He takes pictures of food presentation — meat and cheese boards, how the asparagus is propped up on the plate. He studies architecture — the lines and leans in Tokyo’s buildings, the gates in Budapest, Venice’s marble floors, a colorful glass ceiling in Cuba. All are inspiration. Elements of the bar at London’s One Aldwych Hotel — liquor lining the window — can now be seen at 21c Durham.

Anywhere he goes it’s open eyes and action.

“I am always moving,” Wilson says.

The clock is always ticking.

*

Wilson speeds through time, speeds up time. He’s tight-clocked, especially at art fairs. “When he gets through the doors, he takes off running,” says Brown, who moves with a painter’s slow eye, more methodical in her wandering. “If I follow him, I’m at odds with myself.”

Local filmmaker Edward Heavrin scrambled to keep up with Wilson at the 2014 Art Basel fair in Miami. (Heavrin first saw Wilson’s red glasses during a party he catered at Woodland Farm, where he watched Wilson zipline into a farm pond, a signal the party was over, goodnight.) He was working on In Frame: The Man Behind the Museum Hotels, a documentary about Wilson that screened at the Kentucky Center this April. The film captures Wilson’s decisive — some might say impulsive — approach to buying art. “He always asks, ‘What’s the story behind this? What does this mean?’” Heavrin says. “If the gallery owner can’t tell him what the piece means in 20 seconds or less — if it’s too long-winded or doesn’t make sense, too avant garde — he loses interest.”

Wilson doesn’t want to miss what excites the eye. Doesn’t want someone to steal a piece out from under him. He once told Heavrin, “I only have remorse for the things I didn’t buy.” Like that Kehinde Wiley painting at Art Basel. Wiley reworks history by inserting color, the African-American, into classic white portraits — he knocks Napoleon off the rearing horse and replaces him with the street man, Timberland boots on, bandana tied, pointing with authority. Wilson was smitten when he saw the bright, ornamental background of this familiar artist — four of Wiley’s works are now in the 21c collection — but nope. Sold. Not his. Gone forever. “Missed it by minutes,” Wilson says. “It’s hanging in the lobby of the Brooklyn Museum now.”

But there’s always more art. In less than 40 minutes at the fair, he purchases three pieces for $117,000.

“Anything over $20,000 is something to stop and think about,” Wilson later says, referring to 21c’s art budget, which he declined to disclose. “It sounds like a lot to some, but nothing to real art collectors.” He builds each 21c around four or five permanent pieces. For example: 21c Louisville’s “Text Rain,” an interactive installation that projects falling letters and the viewers’ bodies on a wall, words collecting on heads and shoulders.

At the fair, Wilson sees a stack of bricks, each stamped with space trash, satellite or shuttle debris.

It takes no time.

Sold.

A bust of encyclopedias sculpted with a chainsaw.

Sold.

More bricks, this time on a bicycle. Wilson gets it. The stress on labor. Wilson has seen bricks transported in the same way. A man with ten donkeys and every donkey loaded with bricks. Women carrying bricks on their heads.

Hard work. The memory of long days on Wilson’s father’s farm. Wilson had asthma and was allergic to everything — the hay, corn dust, animal dandruff — and would struggle trying to tend the fields. This disappointed the father that came from a family of farmers. The father who cleared the woods and dirt-farmed. The farmer who only knew work and nothing but work and later in life worked through two cancers, the third halting him to half-days. The Indiana man who moved to Wickliffe — the 800-person town in Western Kentucky — with his loyal wife and Steve, his then-two-year-old son. Into the house on stilts in the river bottom. No running water. No electricity. “James A. Wilson and Son” tattooed on his father’s truck. The son. The namesake. “The sissy.”

At the art fair, Wilson finds the young dealer, a lady from Brazil.

“$15,000,” she says.

“One-five?”

“One-five.”

He turns to Brown and 21c museum director and chief curator Alice Gray Stites. “Are you okay with this? I think the price is good on this.”

He leaves Gray Stites to handle the details.

*

The sexy black Audi pulls into the Honaker Aviation parking lot in Sellersburg, Indiana, 12 minutes before takeoff. The private aide, in his 30s, his hair slicked back in a curly bun, drives Wilson 120 to 150 miles a day. The glasses Wilson bought on a whim in Paris — the red frames that have become the fruit of his face — gleam through the tinted windows.

There is no real rush. Fly-time is Wilson’s time. This is 21c’s private jet. No gates close on the worried traveler with a quick connection. No plane lifts until he tells it to. Today’s trip: to Oklahoma City to check on a 21c hotel under construction.

Craig Greenberg, 21c’s president, waits inside the Honaker building with a buttoned-up coolness, ready for business. He is a Harvard graduate and, before 21c, knew virtually nothing about art. “He was just a boring lawyer,” Wilson jokes. Wilson and Greenberg met on a “professional blind date” and Greenberg advises Wilson on business decisions. “He has made me much more comfortable with pushing the envelope,” Greenberg says.

“So, we’re on for New Orleans tomorrow?” Wilson asks, his voice soft-murmury, hard to catch.

Greenberg nods at the plan to scout potential 21c properties in New Orleans.

“I need to go to physical training in the morning,” Wilson says, referring to a strained shoulder. (He drives horse-drawn carriages in competitions, and his shoulder pain makes it hard to control the reins. He’s the 2015 United States Equestrian Federation’s National Pair Driving Champion.) This April morning, that shoulder is ensconced in an Italian Etro patchwork blazer — navy blue, velvety, plaid and paisley. (His flamboyantly floral suit from the 141st Run for the Roses is on display at the Kentucky Derby Museum through the end of the summer.)

Greenberg talks numbers, beverage sales. When Molly Swyers, 21c chief brand officer, arrives, there’s a nod to the young pilot and soon the Citation II is taxiing down the runway. The jet is fancy: comfortable seats, an assortment of fruit, Babybel cheese. During the two-hour flight, Swyers shows Wilson a picture of the rooftop penthouse deck and points out its water tower (which Wilson once climbed and will later describe as the “biggest hot tub in Oklahoma City!”). They discuss the ballroom floor, a permanent art installation made of laser-cut metal with an inlay collage of eyes, hourglasses, an “Open” sign and an androgynous bathroom symbol that all kaleidoscope into a mandala. Swyers, who has the soft directness of a mother with a young son, minds the details, taking notes on her squint-worthy checklist. Wilson emails on his iPad — tap, tap, tap — fingernails clean and clipped. It’s as if there are no clouds, no fields, no winding brown river below.

Wilson flips through a Sotheby’s art auction catalogue he pulled from his briefcase. All the artists so...dead. Miró, Matisse, Warhol. He pauses on Roy Lichtenstein’s “Nude with Blue Hair.” This dotted damsel hung in Proof when it originally opened. Until Wilson realized it didn’t fit the collection. The work was too modern, too mainstream, too expensive (the copy in this catalogue of “prints and multiples” going for upwards of $500,000. For a print!). The artist too dead. “We can buy a lot more contemporary artists, young artists, and help them, versus buying one $500,000 piece,” Wilson says.

He turns the page. Hello, Picasso. Wilson remembers you. The first portrait he bought back when he was an art student at Murray State University was a print of yours. The sadness of the subject — thin features, eyes focused on the viewer, on nothing — reminded Wilson of himself. “I envied Picasso’s ability to capture emotion in so few lines,” he says. Wilson says he was the only person with an A in his Murray State design class, but he struggled in figurative drawing, the teacher ripping his drawings off the easel, tearing them up in front of everybody. It was enough to scare him out of art school and into political science.

His father had been mayor of Wickliffe and Wilson liked seeing him as leader of the community. He liked the thought of contributing to society. He was inspired by Robert Kennedy and his advancement of civil rights. Eventually: Frankfort and a 30-year career in politics under three different governors — Julian Carroll, John Y. Brown and Wallace Wilkinson. In that time, Wilson planned events like the inaugural ball, wrote speeches, helped create a new Department of Arts, served as the deputy commissioner of public information and as executive director of a governor’s mansion restoration project. But: “I was trying to be someone I wasn’t. Saying all the right things all the time,” Wilson says. “I learned the politicians I most respected were very often not honest.” He was disillusioned with gifts of cash, unreported contributions, unfaithful husbands.

In Carroll’s administration, in the late ‘70s, Wilson met his first wife — the governor’s sister, Jane — and they had a son, J.B. In the next administration, they divorced. He describes his life then by quoting a Talking Heads’ song: “And you may tell yourself / This is not my beautiful house! / And you may tell yourself / This is not my beautiful wife!” After the divorce, he spent a day in the Rodin Museum in Paris, wandering around, looking at the same statues over and over. Sculpture had been his art-school favorite. “The Gates of Hell.” “The Lovers.” He liked the looseness, the movement in bronze, the paradoxical softness of the hard medium, the fact that Rodin could leave work rough, unfinished. “Especially compared to the classic Greek and Roman statues. Those were fine, smooth, stylized. All those things are perfect,” Wilson says. “Rodin was able, as an artist, to get past that.”

*

Steve Wilson cannot get past that because Steve Wilson is a perfectionist. At the site in Oklahoma City, he analyzes everything. This 21c took over an old Ford Motor Co. assembly plant, the original sign still on the exterior. The building was passed down through several generations of one family; this generation formed a partnership with 21c to save the building, a $47.5 million project. Wilson marvels at the original columns repeating through the halls like tall, thick bones. A team of workers moves like ants through the building, marching through their tasks — unwrapping dining room tables and fixing exposed wires on the overhead lights after Wilson comments on them.

In the finished suites Wilson, Greenberg and Swyers inspect the furniture designed by Deborah Berke Partners, a NYC-based interior design firm that has transformed each 21c since the beginning. They look for anything to add to the punch list of things that must be fixed, down to a loose thread on a new chair. In design meetings at the 21c corporate office, Wilson and Swyers thumb through fabric swatches. They choose colors with names like “tickle sterling,” “picaro zinc” and “lion leather.” A light fixture looks like a moon with craters, too spacey. If you’re “pedestrian” or “uninspiring,” meet the trashcan, shaped like a crumpled-up piece of trash. He’ll pin good designs onto the long strip of Styrofoam scaling the wall behind his desk. At one meeting they discuss the front desk, and Wilson says, “What ever happened with the idea of not having a front desk at all? And the personnel comes to greet you.”

In Oklahoma City, the sink knobs shaped like wheel spokes thrill Wilson. But a chair is too tall for the suite’s desk and Wilson says they need to get new ones. Art chosen by Brown — silhouettes of an African family — are measured against the wall. Are they best over the chair, or couch? The penthouse has long couches with bronze braided pillows. Wilson looks at the ottoman, says,“That’s big. Does it take up too much space?” The penthouse shower, visible from the bedroom hallway, inspires a conversation about modesty, voyeurism.

Everything must be perfect.

Wilson doesn’t think he’s ever actually reached perfection. He knows he has high standards and can be quite critical. He says he thinks perfectionism is a flaw, but then says, “I don’t think 21c would be what it is if I didn’t have the desire to make things perfect. I have no desire to build Holiday Inns.”

As for his personal life, Wilson says he wishes he could’ve been a better father. His adult son, a contemporary artist who has a couple installations in 21c, didn’t return phone calls for this story. Brown remembers when she first saw the two together: “It was like talking to twins.” At Wilson’s granddaughter Bradley’s graduation from St. Francis Middle School, Wilson finds his 15-year-old grandson, Avery, first. Holds him sweetly by the neck, gets a good look at him, the nature boy. They worked together on a treehouse Wilson designed that was featured on Animal Planet’s Treehouse Master. Soon, they will be going to Canada, just the two of them, to visit a cabin Wilson bought but hasn’t yet seen. Little Mae — a look-alike of Wilson’s mom, he thinks — has just finished fourth grade, knows the weight of baby bison, talks assuredly while she balances the graduation program in her hand. Bradley wears white with the rest of the eighth-grade girls. She wins an athletics and an arts award, and gives a speech, says, “Sometimes I’ll think about a situation I’m in and think of it as a memory. How I’ll miss the person I am in that moment.” Wilson and his son sit side-by-side, sit the same way — right hand on crossed right leg. Their glasses sit on their same nose the same way.

Wishes he could’ve been better for his father. “Even though he’s dead now, I’m still trying to prove to him that I’m good enough. I don’t think that will ever change,” Wilson says. He would’ve liked to have been better educated. He’s traveled the world — in two months he was in England, Canada, all over the U.S. and was planning trips to Switzerland, Italy and Cuba — but: “I know I bring my successes to the table, but it becomes fairly evident that when I’m with people that’ve read a hell of a lot more books than I have,” he says. “You can’t have that conversation and not wish you’d read that book.”

He doesn’t see well enough to read much now anyway. He has something called Fuchs’ dystrophy — which he needs an employee to remind him the name of because, he says, “those details slip” — that lights halos around things and warps facial features of people a table away. Those famous glasses don’t really help. It’s partly why he has a driver. “I get frustrated. I can never be alone, go somewhere by myself,” he says. He can’t read the newspaper or a menu. At today’s lunch in Oklahoma City, Greenberg reads the list of sandwiches to Wilson with patience before he sits with the crew. At other restaurants, Wilson will take a picture of the menu on his iPhone and enlarge it. Before his horse races, Wilson memorizes the course, walking the sharp turns along fence lines, tight circles and jaunts through water. “I have a lot of anxiety about losing my way,” he says.

“I’m sure art would be different if I saw perfectly. I’m not bumping into things. I don’t need a stick to get around, OK?”

*

Suppose the Death Clock was reversed, its red digits moving backward in time, revealing the past. Speeding through deserts and love and heartbreak and Thailand to Wickliffe, and a time when all the clocks were analog.

Dancing through the house. French doors open from room to room to room to move. Wilson, just a boy, with his younger sister Melanie, polka-ing to mother’s piano playing, or embellishing Chubby Checker’s latest hit, “The Twist.” Wilson would choreograph the dances, design the costumes: black velvet, emerald stones sparkling, organza billowing out of the calypso headdress. The siblings would cha-cha, cross step, revel in the freedom from the farm and long days spent vaccinating and cutting cattle and “chunking” — clearing the fields of debris after the river bottom flooded.

Wilson as a boy in Wickliffe.

Wilson’s dad — who eventually had enough farming success to move the family off the stilt-bolstered house and into a big brick house that was once owned by the town banker — wanted Wilson to do the two things he, the father, couldn’t: fight and dance. “Luckily Wickliffe didn’t have a boxing teacher,” Wilson has said. “But I quickly became the favorite student at the Anita House School of Dance.” In eighth grade he planned his own recital: a witch-doctor dance, complete with black leotards and masks and an African drum record. “I wanted a big fire in the middle of the stage, but since that was out of the question, I got those little chicken-pot-pie cans my mother collected and that sandy stuff mechanics used to soak up oil on the floor in my dad’s farm shop,” he says. “Because I’m a risk-taker, there was no dress rehearsal. I lit my little diesel-soaked fire pots, opened the curtains, and shocked the hell out of the little town of Wickliffe.” Smoke filled the auditorium and the school had to be evacuated. Wilson’s father — by then the town mayor — was horrified.

Wilson once drew a horse on his bedroom wall without asking, and his mother installed a frame around the realistic rendering. Another time, he tried molding his little brother Brett’s face into a death mask. At a party Wilson threw for his 4-H buddies, he transformed the house into a tropical paradise, with water pouring over a metal trash lid like a real-life waterfall, a maze of gang planks in place of porch steps and netting that dangled from porch columns, stuffed full of kudzu Wilson and his sister collected. A barrel of burning diesel fuel like a Western Kentucky volcano. His sister, Melanie Wilson Kelley — who is admittedly less creative, more methodical, the good student in school, and now a lawyer — always helped him pull off the ideas. She idolized her brother. “Dad was a tough task master with a very strict worth ethic,” she says. “Solidarity in the face of that made us close, or even closer.”

Wilson with parents James and Martha Wilson.

But dad never understood. Not even when Wilson documented in the local newspaper the sawmill his father, as mayor, brought to town. While cutting cattle on the farm, two separate times a horse fell on Wilson’s leg, breaking it each time, subsequently messing up his hip. (Wilson has had three hip replacements and walks with a slightly uneven gait.) Would the risk-taker in Wilson — past, present, future — ever win his father’s respect? Or were all those accomplishments — the 4-H horse and calf projects, the 4-H state council vice presidency — lost on him? When Wilson’s dad bet against 15-year-old Wilson’s plan to ride a horse 280 miles to the Kentucky State Fair — which he did, an 11-day trek “wearing out three horses and my bum” — was it because his dad thought he lacked stamina, courage?

Sometimes it’s hard to see what’s right in front of you.

*

“My life doesn’t make any sense,” Wilson says over a plate of fried chicken at Proof on Main. Proof: Where the host says, “You’re with him?” and Wilson doesn’t let the waitress take his plate away till his company is finished. Where the neon wallpaper, itself an art installation, blooms with pictures of Woodland Farm flowers. The “PDR,” 21c lingo for “private dining room,” is a shrine to Wilson and Brown. On one wall, the Death Clock, still alive and well, a blur to Wilson from his seat.

Wilson wonders where he got his talents. “The things I’m good at, the things I’ve accomplished, have nothing to do with where I was raised. Some people say, ‘You have innate abilities.’ Where does that come from? My mother was a musician. You could say, genetically ... I was raised to be a good dirt farmer. I wasn’t around art, ballet. I never saw anything creative till we got a TV when I was eight. First time I saw anything outside the world of hard work.” (He’d watch The Ed Sullivan Show, The Original Amateur Hour hosted by Ted Mack.)

Could he possibly be some dead creative, passed down, alive again?

Wilson says he doesn’t know who he’d be the reincarnation of and he doesn’t want this “article” going into “la la land.” (Later, he texts, “Just remember, we want the Louisville community to respect me when they’ve finished reading this story.” Doesn’t want to be thought of as a “kook.”)

He goes on: “I don’t believe in reincarnation, but I just wonder where my abilities come from. I don’t know. How do I identify art? I don’t know. It’s an emotional reaction and it seems to be an ability that I have.”

Wilson definitely doesn’t want to drown. Not a good swimmer. He’s left-handed. He’s heard left-handed people are more prone to accidents. At least that’s what the actuary test suggested.

Wilson doesn’t believe in heaven. “Certainly no one knows where we go when we die,” he says. He grew up Methodist — his parents both devout — but religion didn’t take with him. Could’ve been the judgmental spirit of the Word: If you don’t believe in my heaven, you’re a sinner! He guesses he was baptized as a baby, but his sister remembers later, Easter Sunday. At church services, Wilson would sit in the pews, look past his mother — the church organist — and daydream that the choir was a band, the sanctuary a nightclub.

When he was 21, Wilson went to Thailand as part of a 4-H Farm Youth Exchange. “I met people that were so pure and good and happy. They were poor, but they didn’t care. They shared when they had nothing to share,” Wilson says, remembering the “bed” a family made for him because they heard Americans slept in beds — a platform of raised boards, essentially the floor on legs. “They were more Christian than Christians.”

He lived with a rice-patty family, then peanut farmers and then on a rubber plantation where at night they’d light the bark of a rubber tree to collect hundreds of sticky, milky white latex sap driblets in bowls. He learned a little of the language, walked the mountains, lived with a Buddhist. He saw the warplanes fly overhead — it was 1969, the Vietnam War — and read about Nixon’s secret Laos bombing campaign in a months-old Newsweek his family sent. Wilson was wide open, learning perspective, the other side of the world.

*

The clock strikes love. It’s the early ’90s and Wilson is riding a camel through Pakistan’s Cholistan Desert with Laura Lee Brown. They’re with a group of friends to walk the old Silk Road. They have three days ahead of them on this humpy excursion, but Wilson cannot control himself — it is too much, this love.

His camel nuzzles up to Brown’s. He grips his handkerchief tighter in his hands, so as not to drop the ring tied to the end of it. Brown opens it, confused — is it a bauble from the bazaar?

They’d talked about marriage before, but Brown was hesitant. She was jaded from a past marriage in which the good didn’t outweigh the bad. Resilient or resistant, the prospect of marrying again was daunting.

Wilson was sure. They’d met in 1990 at a small dinner at 610 Magnolia where a mutual friend sat the two beside each other. If the friend was playing matchmaker, Brown wasn’t aware of it. This woman — the debutante, the silver spoon — so different from Wilson, yet familiar. Her heart in the land, her eye full of art. “I fell in love before she could ever remember my name,” Wilson says.

When Brown later invited Wilson to a dinner party, he could barely contain his excitement. When he got there, he was put at a different table than her. “I didn’t know at the time she always separated couples at dinner parties,” Wilson says. He wasn’t sure if he was her date or not. He hung around after the party and she told him, “Time to go.” If this thing was going to progress, it was going to be at her pace. She is deliberate — she sits with photograph subjects for 45 minutes in Tanzania or any place where she feels like an “other.” She spends days painting at home. She’s patient, steady, still.

Now, in the desert, Brown’s day-long deliberation. She puts the ring on, takes it off, puts it on, takes it off. The diamond glints in the sun. Wilson is firm, insistent. Groups of wild camels walk by, their babies trailing, and Brown feels like part of their crew. The sand shifts and sways. The sun sinks, the cool rushes in. They’re in the tent now, legs sore from balancing on the Bedouin saddles — stiff boards without stirrups — and finally Brown says, “If you promise to not make me get back on that camel, I’ll marry you.”

They were wed in October 1993 in the Woodland house that had yet to be renovated. Brown shivering in her mother’s pale peach satin dress. The nine fireplaces lit. The rest of the light came from candles. The next day, they were off on a trip around the world. “Steve had planned it all. Didn’t tell me where we were headed. That’s part of his M.O.,” Brown says. “Surprises.”

Wilson was aware when he married Brown that some people would question their relationship and his motives. He’d married the heiress. He was anxious about how he’d contribute, find his place in her world and her family. He didn’t want to be thought of as Brown’s “boy toy.” “Two people in love — outside perceptions shouldn’t matter, but it has mattered to me,” Wilson says today. “I think it’s a lot of what drives me. We have 1,000 employees at 21c now. All those people are being paid by money generated by the company. They’re supporting their families or education. Surely people couldn’t still be thinking that....”

*

The gravel road that runs through Woodland Farm is bumpy and follows a little creek. Pawpaw and sumac trees rise, evergreens tower and shade. A monarch butterfly lifts off. Deer jump the brush. Two giant green plastic bunnies sit in a field, whimsical cousins to the 21c penguins and the pink snails clustered at the farm’s entrance. Farther in, there’s a garden that supplies Proof with basil, asparagus and other veggies. And then, finally, the brick mansion where Wilson and Brown lay their heads when they’re home. The front porch faces the Ohio River, what boatmen used to call “the highway.” Through the windows you can see the occasional barge plowing through the water and, on the Indiana side of the river, farmland Wilson and Brown purchased to prevent a golf course from going in there.

Now, everything is under renovation. From the zebra-print runner lining the stairs to the soft-white grass-cloth walls to the six Asian figures — stiff and pale — hanging upside-down from the two-story ceiling. (Before this, the figures sat in storage at the Louisville Mega Cavern with the rest of the art collection.) “I think Steve would kill me if I told you the amount of money this (renovation) cost,” says Douglas Riddle, president of Bittners interior design firm, who has worked with Wilson on several design projects at the hotel and on the house redesign.

Riddle designed for lightness, art and functionality, with an emphasis on creating space for entertainment. The couple hosts many parties at Woodland, including a brunch on Derby Sunday, Wilson’s favorite day of the year. At the Vanity Fair-sponsored Oaks party at 21c this year, Wilson’s suit sparkled as he two-stepped in front of a wall of roses and had 11 years, nine months, seven days, 14 hours, 32 minutes and 27 seconds left.

Over the living room fireplace, a copper vine twists up the wall, as if nature is reclaiming the house. Louisville native Anne Peabody hand-cut every copper leaf. This amazes Wilson. “It’s crazy. I think of an artist who comes up with an idea and they don’t seem to worry if it’ll take eight days or eight months to complete. They get into it and it doesn’t matter how long it takes,” he says. “I can’t do that. I think about time. Is it worth it? Time worries me.”

Outside, black and white dogs roam free. Birds sing in the trees. Spiders climb the old brick. There’s a cemetery not far from the pond with one tombstone in its thigh-high grass. Wilson discovered it when he and Brown were first looking at the property, which didn’t even have a front porch. He knelt down to read the dates on the stone: born 1812; died 1890. He looked at the grave’s marker, the “omen” awaiting, and saw his initials, so clearly: J.S.W.

*

Two hours of sleep, maybe three. Tossing in the light-blue bedroom and moving to the glossy green room — his “dressing room” complete with daybed — so as not to wake Brown. Awake, antsy, he’ll text Riddle about the tiles in the bathroom, say they need to be six inches higher. He’ll wonder whether the New Orleans property will work out or not. (It won’t.) He’ll remember his rural roots, how the work never stopped; how you can’t turn it off or forget about it. “When the hay is down you’ve got to get it up before it rains,” he says. He’ll “hit his wall” — unscalable exhaustion kicking in after days of airplanes and meetings. He’ll have a sleeping-pills prescription filled, finally sleep, but yawn all the next day, and at a design meeting Swyers will say, “You look tired, but I’m glad you slept. Sometimes when you actually get sleep, you need more sleep. Don’t you think?” And he’ll respond, “I think so. What is this fabric?”

Sleep or no sleep, it’s 7:30 a.m. and Wilson has already ground and brewed his coffee, and is prepping for the first meeting of the day. He walks to the hot tub out by the pond and sinks into its steam. One hundred and four degrees.

Wilson’s nephew, Woodland Farm manager Kristopher Kelley, takes off the 21c robe Wilson gave him, hops in. In this daily morning meeting where Wilson may or may not be naked (“You’ll have to ask him,” Kelley laughs), the two discuss moving bison from field to field. The farm is getting away from pesticides, and as the grass grows, the bison must rotate. (Once the president of the National Bison Association, Wilson brought a trained bison to Capitol Hill as a lobbying tactic.) They talk about Woodland’s sawmill and biodiesel facility, about their meat-processing plant in Indiana.

The planning goes on for 30 minutes to an hour. Geese fly over the pond and give the faintest whoosh. It is hard to leave a place that is so comfortable, but there’s still so much to do.

*

On May 27, Steve Wilson has 11 years, eight months, 18 days, zero hours, 52 minutes and 34 seconds to live.

Long legs stretched in the back of the Audi, he calls his sister. They talk about an uncle who has recently died and been cremated. Wilson had planned to be cremated, but after seeing that tombstone near his house bearing the ominous initials, he changed his mind: Now he wants to be buried in a pine box by his home.

There’s purpose in 11 years. He wants to make Hermitage a successful operation, get his farms protected by conservation easements, see his grandkids grow into adults. He’d like to travel to Haiti, Fuji. There could be 21 21c Museum Hotels finished by then — New York City, New Orleans and maybe even Cuba, Wilson's big goal now that the travel laws have started loosening. A whole slathering spectrum of penguins. “Got a lot of art to buy in 11 years,” he says.

Wilson doesn’t think he’ll make it to the end of the countdown, to zero. As much as he doesn’t want to slow down, he sees his body deteriorating: the blurred eyesight, that nagging shoulder. He has been diagnosed with a degenerative joint disease of the spine that has caused muscle atrophy in his upper left arm and numbness in his middle three fingers. Treatment so far has been epidurals, but he’s scheduled to have surgery in June (“by the same doc who fixed Peyton Manning”). (Post-surgery in Los Angeles, he says, “I’m going stir crazy in the hotel.”)

“I don’t want to stop,” he says, and there’s a pulse of his father. “I certainly am never going to retire.”

Suppose the clock strikes death and Wilson’s not dead yet. “There will definitely be a party,” he says. It’ll be like New Year’s. New life. He hasn’t thought about specifics of his alive/dead party. But you can picture it: Death masks. Skeletal celebration. Dia de los Muertos, an offering at altars to those who died. Family surrounding. Performers, always and plenty. Sparks.

When the clock’s red digits stop — 00:00:00:00:00:00 —Wilson explodes from the death womb, or creaks out. Everyone dancing as naked as they were when they entered this time-choked world.

This originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find your very own copy of Louisville Magazine, click here.