By: Jack Welch

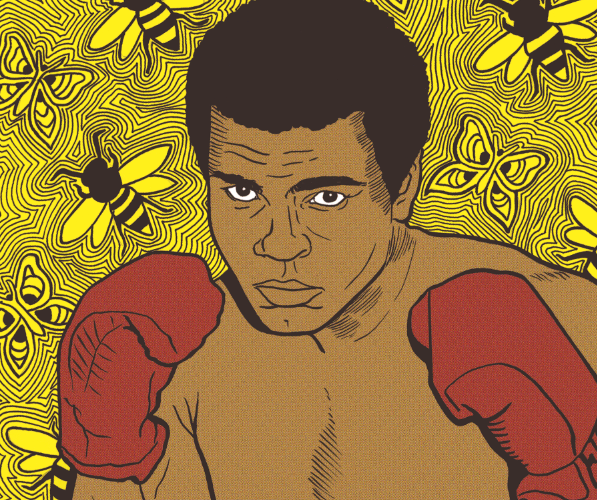

Illustration by Carrie Neumayer

Coincidentally, I had just finished writing my monthly column — on a TV ad that featured computer-generated clones of Muhammad Ali — the day before he died. On Thursday I was in a research reverie, Googling all kinds of nifty anecdotal memory-joggers about the guy who bombastically proclaimed himself “The Greatest” way back when I was a 15-year-old; on Saturday morning I was staring at the Courier-Journal front page, dumbstruck by the passing of my generation’s most momentous historical and cultural icon.

In Sunday’s New York Times, seven Ali-smitten staffers wrote tributes covering more than eight pages, with a wondrous variety of photographs — shots of him in the ring standing over Sonny Liston, dodging a Joe Frazier left hook, tagging George Foreman with a huge right; of him so wild with exuberance after the first Liston fight that a trio of his laughing handlers couldn’t restrain him; of him entering a taxi in Times Square amid a sea of admirers; of him impishly tweaking a hair on Howard Cosell’s toupée; of him posing bare-fisted as a 12-year-old; of him refusing military induction; of him hanging with Malcolm X; of him lighting the Olympic cauldron in 1996; of him hugging his daughter Laila before one of her own boxing bouts. The Courier matched the Times’ acclamation and more, with 13 of its current and past columnists and reporters acknowledging the huge loss of Louisville’s most remarkable native son.

To be sure, Ali’s contributions to the American social process during the 1960s and ’70s, especially, are the stuff of unending argument. He was gabby; he was boastful; he was brash (“I’m the prettiest thing that ever lived”); he was self-righteous; he was frank; he was confrontational. Those qualities alone made him magnetic to some and despicable to others. When he declared himself a disciple of the Afrocentric Nation of Islam in 1964 and forsook his birth name (“my slave name”), many people admired his openness and conviction. Detractors, though, derided the announcement as either a publicity stunt or an endorsement of black revolutionary behavior and gloated in continuing to call him Cassius Clay.

Two years later, when he defiantly informed the press that he would refuse military induction (“I ain’t got nothin’ against no Viet Cong; no Viet Cong never called me nigger”) — ultimately accepting a 43-month exile from boxing — it caused a sizable segment of the American public to reconsider the morality of the Vietnam War. To the rest he was just a selfish draft-dodger.

I’m in the admiring camp. I remember back in late 1990, when the neocons were gearing up for the first Gulf War, and Ali — six years into his Parkinson’s, with his voice just a whisper — flew to Baghdad against the State Department’s wishes and pleaded with Saddam, Muslim to Muslim, to free 15 American hostages. He got it done. And what was the predominant reaction back home? That it was a publicity stunt. “I do need publicity,” Ali told the press, “but not for what I do for good.”

This originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find you very own copy of Louisville Magazine, click here.