By Jay Gulich

Photos courtesy of Ed Garber

Notwithstanding the fact that he was Jewish, and that neither of my parents officially bestowed the title on him, I always considered and frequently referred to Marty Sussman, the recently deceased former owner of the fabled repertory theater the Vogue and eminence grise of independent film in Louisville, as my godfather. It was a point of pride. Marty was cool. And somehow, as a 10-year old at the dawn of the 1980s, I picked up on it before I even knew what that meant.

My first inkling of Marty’s cool quotient was his laid-back work ensemble. In the days before business causal, most working men I knew, including my own banker father, wore a suit and tie to the office every day. Marty favored loose, well-worn jeans, low-profile loafers and cotton or linen dress shirts, always open to the second or third button. Despite the fact that he seemed to be losing his thinning hair from the first day I met him, he patted and fussed over it like Warren Beatty’s George Roundy in the ’70s film Shampoo. With his smiling mischievous eyes and weathered visage, Marty forever reminded me of Leonard Cohen, another urbane mensch from Montreal.

Then there were the things he introduced me to at various points in my young life: Betamax (followed soon after by VHS); handicapping horses on TV via TVG; the music of Chet Baker; HBO and the nascent cable TV universe; Japanese anime; Indian cuisine; bagels (unfortunately they were the Lender’s frozen variety, but what other bagels were available in Louisville in the early 1980s?); Some Girls by the Rolling Stones; Andy Warhol and his Factory; and the epicurean delights of 610 Magnolia (orchestrated by his buddy, 610 proprietor Eddie Garber). All of these things were indelible, and many of them still resonate with me deeply as an adult.

Long before the Urban Bourbon Trail, farm-to-table cuisine, 21c or the other hip Louisville things that have appeared in the New York Times, there was the Vogue Theatre. And there would never have been the Vogue that I grew up with without Marty’s vision and loving stewardship.

The Vogue Theatre

My earliest memory of him is his orange lift-back Chevy Vega littered with Vogue calendars. Marty loved movies and he curated the monthly Vogue calendar like the eccentric, wily businessman with an artist’s heart he was.

Louisville was not exactly cutting-edge during this era. But to look at the Vogue calendar from those days you wouldn’t know it. David Lynch’s Eraserhead juxtaposed with City Lights, starring Charlie Chaplin, showing just the day before Yellow Submarine and its animated cast of John, Paul, George and Ringo, or the trippy visual tone poem Koyaanisqatsi, with compositions by Philip Glass. Not to mention the amazing concert films: Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains The Same, Pink Floyd’s The Wall and the Who’s Quadrophenia.

This was heady stuff for any city in Middle America at the time. (Hell, it would be today.) And as great as the entire calendar was, my most vivid recollections of the Vogue, and I think this is true for many people, involved the midnight shows. You may ask what a 10-year-old was doing at the midnight movie, but I’ll defer to my parents on that. The fact is, Marty’s stepson, Drew Daniel, was my constant companion during this time in my life. When Marty went to work at the Vogue, typically around 11 p.m., we often tagged along.

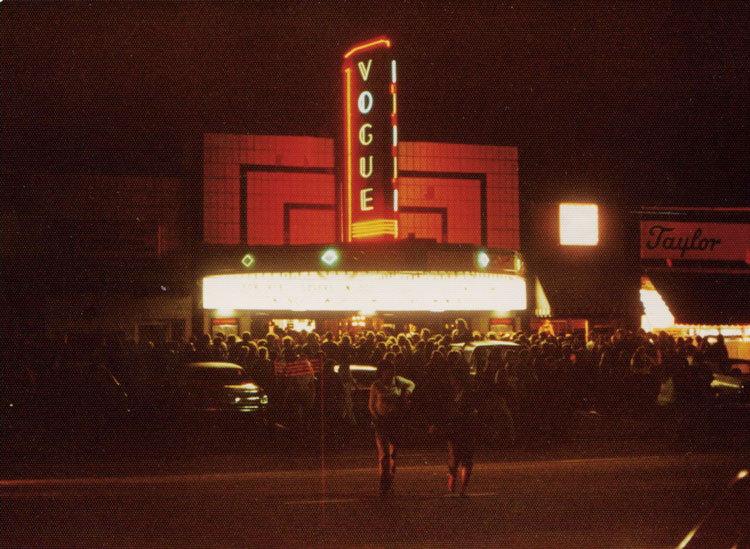

I will never forget the palpable excitement of being at the Vogue for the midnight screenings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. To get in there was almost always a line, frequently stretching on the sidewalk past Taylor Drug and around the corner. Bewildered St. Matthews residents drove past invading teenagers with pink hair and bright red lipstick who peacocked about in black leather and fishnet stockings, sucking hungrily on cigarettes in the neon glow of the Art Deco marquee. There was Frank-N-Furter, Janet, Brad, Eddie, Riff Raff, Magenta and the Criminologist, the last being wheeled down Lexington Road with a blanket in his lap and an elongated cigarette holder in hand like a B-movie version of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Walking into the Vogue with Marty on Rocky Horror nights was like being a roadie trailing behind a rock star. He was in his element, surrounded by acolytes, and the energy was palpable, sexual and liberating. Young people loved Marty, as did drag queens, artists and anyone who colored outside the cultural lines. He was one of the least judgmental people I’ve ever met. And though twice or more their age, he was clearly fueled by the passion of youth.

Sussman in his Rocky Horror days.

Rocky Horror screenings typically opened with three music videos: “Paradise Garage” and “I Do the Rock” by Tim Curry (aka Frank-N-Furter) and “Bat Out of Hell” by Meat Loaf. I will never forget the image of Meat Loaf sweating copiously in an open-necked ruffled tuxedo shirt, waving a sheer maroon scarf like a corpulent toreador.

Then the lights would go down. You’d hear the first notes of “Science Fiction/Double Feature” and a pair of bright red lips would flow into the foreground of the title sequence. For the next 100 minutes you’d be transported to a strange and wonderful land with an unforgettable collection of characters, jumping to the left, stepping to the right, putting their hands on their hips and pulling their knees in tight. All presided over by “a sweet transvestite from Transsexual, Transylvania.” And that was just on the screen.

At the Vogue, what was going on in the audience in response to the movie was equally as entertaining as what was on the screen. From the rice being thrown at the film’s opening wedding sequence, to the newspapers that audience members held overhead to combat hundreds of squirt guns (mimicking the film’s rainy scene outside the castle), to the rolls of toilet paper flying like projectiles at Brad’s cry of “Great Scott” — participating in the film was as important as watching it. At the Halloween screenings, Marty would let a guy dressed up as the tragic rocker Eddie rev his engine and ride a motorcycle up and down the aisles of the theater.

In the mid-1990s, after having sold the Vogue, Marty built the first new neighborhood multiplex cinema in the Highlands — Baxter Avenue Theatres. From the lobby murals by artist Mario Muller to the floating ceilings in the restrooms to the line drawings of famous directors in the theaters to the eclectic programming mix, Marty’s imprint was everywhere. Following a successful opening run, a business dispute forced his hand and he eventually decided to leave Louisville for good.

He and his family settled in the Bay Area. I visited them once in the mid-’90s and then saw them again at my wedding in 1998. When I heard about his death in February I hadn’t seen or talked to Marty in nearly a decade. I regret that we lost touch. But as is so often true with the most important people in your life, you don’t realize how important or impactful they have been until they are gone.

At some point in every life the credits must role. I ran into our mutual friend Eddie Garber on Frankfort Avenue in March. He had been with Marty not long before he died at the age of 83. He told me Marty went out and looked at the ocean, got into his bed and never woke up. An ending right out of a movie. Marty wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Sussman in a recent photo.

This originally appeared in the May 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find your very own copy of Louisville Magazine, click here.