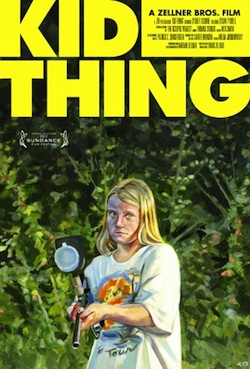

The utterly heartbreaking thing about Kid-Thing isn’t that the main character Annie takes out her anger on all those around, it isn’t that Annie suffers so deeply, and it isn’t that she loses most everything by the end. The truly sad thing about this story is that she stays so silent and alone throughout it all. In the final screening of the Flyover Film Festival, Austin filmmakers David and Nathan Zellner present their surreal tale of a young, tomboyish girl and her deteriorating patience with the negligence and solitude that life has given her. It tells an aching fable about what can become of desperation by those that are too young to properly know that they despair.

Kid-thing follows the thieving, pranking, abrasive Annie through the whirlwind that she creates until she hears pleading cries for help from a deep hole in the middle of the woods. Set in the decidedly quiet Texas countryside, Annie’s life is spent barely observed by her father, who she calls by name. Friendless and unattended, she fills her time as she can, with destruction and ambivalence. That is, until she hears an old woman screaming, deep down into the sightless black of an unexplained pit. Her first instinct is to run away.

Eventually, she makes peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and steals Capri Suns to drop down the hole, tossing a walkie talkie to keep contact. Yet still she refuses to get help. The interesting question that shows the depth of this movie remains to wonder on why? Many answers jump out, but the most important is that it resembles a companionship nothing like she has. Watching her wrestle with whether to keep this contact or assist in her loneliness gripped me. The Zellner brothers found a marvelous balance in humanizing this poor, disastrous child.

Also, the unseen woman, crying and screaming out of the framed hole in the middle of the woods seems to vocalize precisely what I imagine Annie holds in her heart, begging the question of whether anyone is down there at all. Clearly, this is left up to viewer interpretation and rightfully so. The poise of the film’s drama hangs equally melancholic and beautiful on either scenario and literal explanations are unnecessary to tell Annie’s story. The Zellner brothers realize all of this, smartly and cleanly telling a darkly whimsical tale.

In the screening’s subsequent question and answer session, the most vocal of the festival, the audience showed a decided split in regards to whether Annie deserves any sympathy for her actions. This modest reviewer found the reasoning in enough of her actions to understand the raging torment below her still surface. I return to what I said before about her quiet solitude, and how it surrounds this film, letting each interpretation roll around in it. I keep remembering the scene where she locks herself in a bathroom to turn on the walkie talkie and hears the old woman wailing and crying. I was utterly moved to think that Annie could let herself cry in this way. And I was equally shaken by the thought of Annie simply listening and curious at another’s pain. Truly, this movie eloquently explored this troubled child, and it could not have ended any other way. Though it was indeed a sorrowful note on which to end this year’s Flyover Film Festival, it was also an exceptionally masterful one.