Read this article on our newly redesigned website here.

This story originally appeared in the August 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

As his parents pulled into the driveway, Jack Harlow had a question from the backseat. He was 12. “Mom,” he said, “how do I become the best rapper in the world?” His mother had just read the book Outliers, which popularized the theory that the secret to greatness is 10,000 hours of practice. With Jack’s 18th birthday as a deadline, she did the math. For the next six years, her son would need to work on rapping for four or five hours every day. “OK,” Jack said.

Jack Harlow is in the driver’s seat of the 2005 Pontiac Grand Prix he bought off his grandparents for $2,000, lead-footing down dark and drizzle-slicked Cherokee Parkway on the way to his Thanksgiving Eve concert. The speedometer’s needle ticks toward 50, 15 over the 35 mph speed limit. Harlow and some friends are returning to Headliners Music Hall after a pre-show dinner at the Highlands Qdoba, though Harlow didn’t eat because his stomach typically won’t let him before a show. Which is saying something because he has even rapped about Doba, as he sometimes calls it: “Pinto beans in my burrito, roll it up and shove it in me.” On his phone inside the restaurant, he pulled up a WAVE-3 interview he’d done to promote tonight’s gig. “He’s actually kind of adorable,” anchor Dawne Gee said after the segment, “but I don’t know if a rapper likes to be called adorable.”

In the backseat, Harlow’s roommate Chauncy Craighead, who goes by Ace Pro, is on FaceTime with DJ Ronnie O’Bannon, aka Ronnie Lucciano, aka Lucci. “Let’s see the crowd!” Craighead says to O’Bannon, who’s already onstage. A couple hundred fans are sardined toward the front. “Oh, shit!” Craighead shouts. Harlow swivels his head and snatches the phone. “Oh, shit!” he shouts, his face transforming into a real-life toothy and dimpled smiling emoji. “This show is gonna be fire!” (Quick attempt at translating: “Fire, dope and crispy are synonyms,” Harlow says. Yep: crispy.) His longtime friend Urban Wyatt is riding shotgun and asks to see the screen too. “It’s gonna be so lit!” says Wyatt, a photographer and self-described “creative-director type” with blond locks that would make a Disney princess jealous and high-top sneakers that say “Fuck Em” all over. The car lists across the double yellow line.

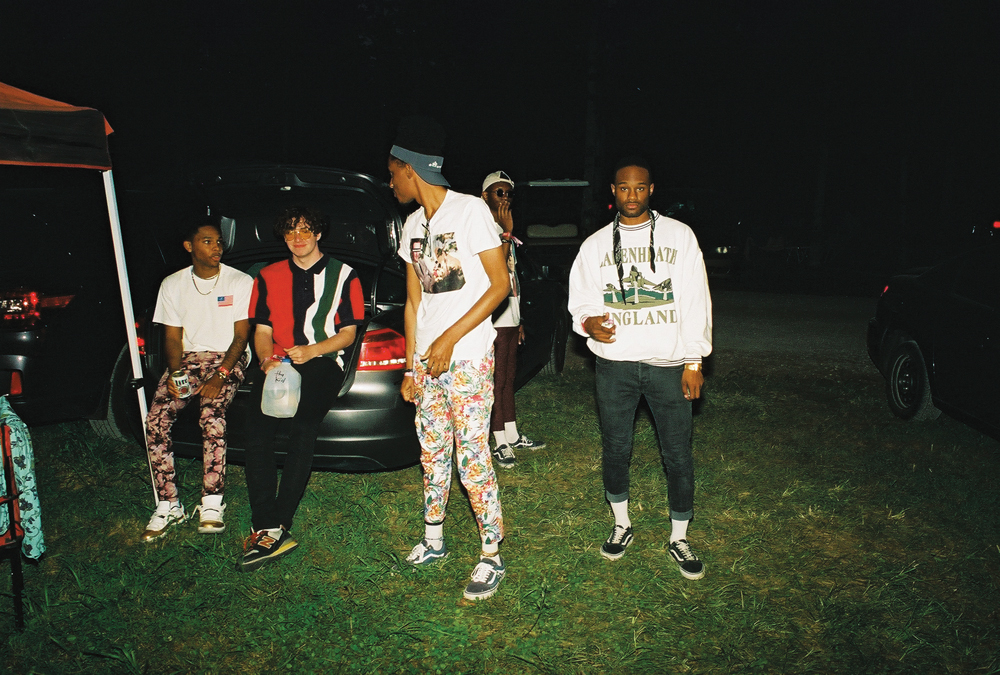

Photo: The Private Garden: Lucci, Harlow, 2fo, Shloob and Ace Pro at Bonnaroo // Urban Wyatt

Moments before parking on the side of Headliners, Harlow pulls up the hood of his ’90s-era, neon-accented Nautica parka, to conceal his identity from the kids waiting to get inside and to protect his corkscrews of brown hair from the raindrops. All night he has been wearing plastic grocery bags over his New Balance sneakers, which he buffed with a toothbrush and a laundry detergent-water mixture while choosing his outfit for this evening: khakis with cargo pockets, and the Nautica over a hockey jersey. Harlow owns more than a dozen pairs of New Balances, every color in the spectrum, but the brand got press recently because a higher-up at the company made favorable comments publicly about then President-elect Trump. A white-supremacist website claimed the company made “the official shoes of white people.” Photos of New Balances on fire — actual fire, not dope fire — or impaled with knives made the rounds on social media. “Like they haven’t always been the shoes of white people,” Harlow says. “It just obviously makes it worse when neo-Nazis say it.”

Harlow — who had meetings with Def Jam Recordings and Atlantic Records during his freshman year at Atherton High School, class of 2016 — released his most recent mixtape, 18, less than a month after graduating. One of the T-shirts at the merch table features the 18 cover art: Harlow striking The Thinker pose in nothing but gray boxer-briefs and his signature black-framed Brooks Brothers eyeglasses. He released The Handsome Harlow EP in November of his senior year, and another T-shirt has its minimalist art: hair depicted as smoke swirls above the glasses. The green and pink pastel panties sell for $10 apiece. Harlow got them in bulk during a Victoria’s Secret sale and had “Jack Harlow” printed across the butt. Check Twitter after a show: “blessed to have received underwear from @jackharlow.”

Harlow enters the venue through a side door and, hood up and head down, goes straight for the green room. At the barricade, a young girl cries, “Was that Jack?!?!” over bass that would register on the Richter scale. She and the majority of the crowd bear the markings of the underage: a Sharpied black X on the back of each hand. “The mean age tonight is gonna be like 16½,” is how Harlow puts it.

In the green room (really more of a maroon-ish room, if we’re going by wall color), Harlow tears the plastic bags off his feet, balls them up and shoots them into the wastebasket. “Jack really killed it with the plastic bags,” Dawoyne (2forwOyNE, or 2fo) Lawson says. “He’s gonna name a song ‘Plastic Bags.’” Lawson’s twin brother, DaEndre (Shloob), sits on a folding table. Shloob is eating Sour Straws. During sound check, Shloob said, “When I played here the first time, the stage looked bigger. It doesn’t look that big right now.” Harlow, who was standing next to him, noticed a NO CROWD SURFING sign and said to nobody in particular, “Can I crowd surf? Wait, why the fuck am I asking? This is a rebellious-ass genre.” Then: “Are cuss words allowed in Louisville Magazine?” A Jack Harlow profile without profanity would look like a redacted CIA document.

The twins, Ace Pro, Lucci and Marquis (Quiiso) Driver are a group of 23-year-old rappers/singers/producers/beat-makers named the Homies, part of Harlow’s Private Garden collective. If Wyatt’s not around, Harlow is used to being the only white guy in the room. On “Hitchcock,” a single he’ll release in February, he raps, “I’m just a guest inside the house of a culture that ain’t mine and I’m just blessed to be around.” And: “I’ve been trying to find the next step to make my best friends rich.”

In the maroon-ish room, the guys sit on metal chairs with cushions a shade darker than the walls. They scroll through Snapchat on their phones. Wyatt plays a little Pokémon on his handheld Nintendo DS. Harlow spies a 24-pack of water, which reminds him: “We need to designate untouchable water for the stage. Gotta have hella water to throw.” O’Bannon is still DJ’ing, and the crowd knows every word to every song, including Kanye West’s “Father Stretch My Hands, Pt. 1,” which is about — well, it includes a line about having sex with a model who has “just bleached her asshole.” And the point of including THAT detail in this story is to say that, if you’re lucky enough to be at Headliners tonight, you get to experience the singular pleasure that is 400 mean-age-16½-year-olds yelling, in unison: “And I get bleach on my T-shirt?! Imma feel like an asshole!”

Harlow finds himself alone backstage during the Homies’ set. He removes the parka and jersey he’s been wearing all night, puts them on hangers. He’s feeling feverish, but this has nothing to do with the fact that he is a little under the weather and has been drinking tea all day. “I always get a semi-fever before I go on,” he says. Then, because he can’t get to a bathroom without fans seeing him: “I’m gonna have to piss in the trashcan.” He grabs an empty water bottle and relieves himself.

Photo: Harlow's Thanksgiving Eve show at Headliners // Urban Wyatt

A little before 10:30, Craighead commands the crowd to chant: HAR-LOW! HAR-LOW! HAR-LOW! Showtime. Harlow puts the jersey and coat back on, the plan being to “rip them off sweatily” while performing. He climbs the six wooden stairs and pushes aside the black curtain in the doorway. Emerging from the darkness, wireless microphone in hand, Harlow stalks to the middle of the stage, a captain at the bow of his ship. The shrieking teens are somehow louder than the bass tremors O’Bannon is pulsing through the floor. Harlow tells his fans to bounce and 400 Pogo Sticks form an undulating wave. His limbs flail, as if he’s trying to kick the air’s ass. He stands with one foot on the stage, the other on the aluminum barricade, fist in the air. At times his mouth becomes a word processor going for the syllables-a-minute record. “Y’all are turnt the fuck up,” he says, catching his breath between songs. “Not that I’m depressed, but this is a self-esteem boost.” It seems the only lyric the crowd doesn’t know is one Harlow tweaks: “I don’t fuck with Trump but I rock New Balances.” (About voting: “My dad has always told me how important it is to vote. When I told him I didn’t he was pretty upset,” Harlow says. “I don’t even know if I was registered.”)

Harlow often says he doesn’t have 45 minutes of songs that he likes, so after about a half-hour, he brings his younger brother, Clay, onstage. The final song of the night will be everybody wishing Clay a happy 16th birthday. But then “Happy Birthday” goes right into the first bubbly notes of “Ice Cream,” which by the time you read this will have more than 700,000 plays on Spotify alone. The music video features Harlow and his friends riding around town in an ice-cream truck, and a beautiful woman in a bikini rubbing sunscreen on his pasty body. Tonight, Harlow almost screams the words: “Got the kids going wild like I’m selling ice cream!” His brother and the Homies unscrew the caps off hella water bottles and douse the bounding mass before them. Kids hoist a firefly swarm of cellphone lights into the air. Harlow hops off the stage and raps at the barricade. Hands reach for whatever part of him they can get to. He’ll later say that what he does next is giving the fans too much but, in the moment, he decides to go overboard, drowning in the sea of bodies.

Photo: Harlow's Thanksgiving Eve show // Urban Wyatt

Two weeks after graduating from high school, Harlow moved out of his parents’ Highlands home and into a place on Berry Boulevard with Craighead and another friend, just around the corner from the Déjà Vu strip club not far from Churchill Downs. “In the Highlands, especially in a tucked-away neighborhood like I was in, there weren’t people walking around out front whose lives have been shattered,” Harlow said the first time we met, in August 2016. “You can smell the heroin on people. You see people who are zombies at this point.” Most of his friends had just started freshman year in college. Harlow was “doing shit with PDFs” for his parents at their sign-making business during the day and making music at night and on the weekends. “A lot of people have no idea what they want to do,” Harlow said. “I’ve been lucky enough to feel like I’ve had a purpose since I was 12.”

He said he was at a strange place creatively, basically describing himself as an oxymoron: He writes about his life with as much specificity as possible (“Authenticity is the key to all dope shit”) but doesn’t have much life experience. “I just have to get more in touch with me and figure out the sound I want, who I want to be. ’Cause I still don’t know,” he said.

He had already played the Louisville venues: Headliners, Mercury Ballroom, Haymarket Whiskey Bar and a show at the since-closed New Vintage that was so sweaty — so almost literally fire — that his glasses fogged up. “I rep Louisville completely. Anybody who hears my shit knows I love Louisville,” Harlow said. In his music, he has referenced Bardstown Road and the Highlands — and even the Applebee’s there (“And I been the type to leave a generous-ass tip too,” he raps on “Every Night”). “But a lot of rappers here have a local mentality. If it’s a hobby for you, that’s fine. I just don’t want to be in the same conversation as you. If I hang with people who have goals with a cap on them, naturally mine will too. I don’t get any gratification off being known in Louisville anymore. My aspirations are national.”

Over the course of his first year out of high school — one year is about 5 percent of his life — Harlow would travel to Atlanta for recording sessions; perform sets at South by Southwest, Bonnaroo and Forecastle; release singles, including one called “Routine” that you might have heard on 93.1 the Beat. “I’m young. But I’m impatient,” he said. “It’s crazy to be able to see your prime and not be there yet.”

“I can’t stop rhyming words,” Harlow told his dad one day when he was in middle school. “Every time I hear anybody say anything, I try to rhyme it.” The problem had been going on for 10 days. He was getting depressed. “That sounds so corny — ‘Ugh, he’s a rapper and can’t stop rhyming’ — but that’s really what it was,” Harlow says. “I’d be at soccer practice, and I’d hear words, anything multi-syllable, and would just start rhyming.” As an example, he freestyles: “Urban Wyatt. My Instagram was public, then I turned to private. Good person turned a pirate — see, it’s addicting. It was kind of like subconscious training. I almost feel like it was part of puberty for me.”

Harlow was born on March 13, 1998. His mom, Maggie, played a lot of Eminem while he was in the womb. She and her husband, Brian, like to tell a story from when Jack wasn’t even two years old. They were visiting family in Michigan and having a long dinner at a restaurant. Jack didn’t make a peep the whole night. Another diner approached their table. “He’s like a little Buddha,” the woman said. “He’s a very old soul.” On the playground, Jack would describe his brother as a “friend-making machine,” while he was comfortable just sitting and observing.

The house Harlow grew up in near Seneca Park has a #RESIST sign in a front window, a full-size gumball machine and empty candy wrappers as wallpaper above the kitchen cabinets. The original art on the walls includes a large painting of Buster, a trail horse Maggie had to sell when the family moved from Shelbyville to Louisville when the boys were little, so they could be closer to other kids. The Sugarhill Gang’s self-titled debut, the one with “Rapper’s Delight” on it, was the first album Maggie owned, and she’d play that in the house, along with Gwen Stefani and the Black Eyed Peas.

Photo: Harlow in his basement recording booth // Mickie Winters

All through kindergarten, Harlow had to wear a patch over his right eye in an attempt to make his lazy left one stronger. Kids always called him a nerd, so by third grade he’d learned the words to “White & Nerdy” by “Weird Al” Yankovic and made those same kids laugh. “It affects me to this day. Not in a dramatic, been-through-a-lot way but in how I use humor to interact with people,” he says. He read all the Harry Potter books and a series called Warriors about clans of cats. “I grasped the power of speech and words super-early, and that’s what got me into music,” Harlow says. “Writing rap is just expressing myself through language.” When he was 10 he asked for permission to listen to the explicit albums in his mom’s collection. A Tribe Called Quest, Public Enemy, N.W.A. “A lot of people regard the ’90s as the golden age of hip-hop, but” — you can determine whether or not you’re too young to even be considered a millennial by how you react to what he says next — “my generation, who we’ll be talking about in 10 to 20 years, realistically, is Drake.” Agree? You must use the word crispy.

In sixth grade, Harlow used a microphone from the Guitar Hero video game and a laptop to record his first rhymes. He and his friend Copelan Garvey — “Harlow featuring Cope” — made a CD called Rippin’ and Rappin’. “I wrote all his verses for him, so I wanted that seniority,” Harlow says. They burned 40 copies and sold them at Highland Middle School for $2 apiece.

Early on, Harlow wasn’t sure what to write about. “He was struggling a little bit with the fact that he wasn’t a black kid from a rough neighborhood,” Maggie says. “I said, ‘The one thing I know about writing is they say to write what you know.’”

“Black culture was the coolest thing to all kids growing up, whether they want to say it like that or not,” Harlow says. “But I didn’t want to copy. I didn’t want to steal from it. I wanted to put my own twist on it, tell my story.” His sixth grade science teacher, Walker Swain, produced music and asked Harlow to be on a song he was working on. It never got released, but Harlow rapped, “Texting with some other dude is something that I hate to see, but honestly another dude is something that I’d hate to be.”

He got a professional microphone in his bedroom and started going by the moniker Mr. Harlow. In seventh grade, he gave away 100 copies of his first solo mixtape, Extra Credit, for free. “Kids were wanting them as soon as I got in the damn door,” he says. “They were like, ‘It’s kind of ass and his voice is high-pitched because his balls haven’t dropped, but dude actually made a mixtape.’” He loved how Febreze made his room smell after soccer practice, and the last song was titled “The Febreze Song.” “I use F-e-b just to keep my air fresh. If you think it smells bad I could really care less,” he rapped. “Spray it all day, you can smell around my house. Febreze is the best, so forget about Oust.” The music video featured Harlow and his friends, the Moose Gang, spraying cans of Febreze behind the CVS near his house. Cops shut the production down for a minute because they thought the boys were using spray paint. “I explained I was a rapper making a video,” Harlow says.

His bedroom shared a wall with his parents’ room and, late at night, he’d scribble lyrics in notebooks while the beat vibrated pictures on the wall. “For me, that was a lullaby,” Maggie says. “It was the soundtrack of him at work.”

Sometimes Brian would walk past Jack’s room, hear the music, and say, “Who is that?”

“That’s me, Dad.”

“Wow, you wrote that?”

Harlow’s music obsession left little time for school. “Studying was way out of the question,” he says. “It’s very hard for me to apply myself to things that I’m not passionate about.” At parent-teacher conferences, Maggie would introduce herself:

“Hi, I’m Jack Harlow’s mom.”

“Jack. Harlow,” the teacher would say. “Let me tell you something, that kid is really funny.”

“Thank you. How’s he doing in school?”

“Oh, yeah, he sleeps in class.”

Photo: Harlow's Thanksgiving Eve show // Urban Wyatt

A football coach at Atherton heard Harlow’s music and connected him with a studio in Buechel called Fort Knocks and a producer who goes by Larr B.I.N.O. “Graffiti on the walls, reeking of weed,” Harlow says. B.I.N.O. says, “I’ve watched Jack grow up, from the time when he rapped about being a virgin to saying cuss words to messing around with girls.”

Junior year, Harlow put out Finally Handsome as Jack Harlow, not Mr. Harlow. “I have a very memorable name,” he says. “And my brand is being true to self.” The music caught Craighead’s attention. “His content was childish, but I saw the talent,” says Craighead, who worked on The Handsome Harlow EP and 18. “Most people don’t have that talent at any age.”

Early on, as Harlow’s videos gained traction on YouTube, his parents started fielding calls from potential managers and others who wanted a piece of their son. One of those people worked with Justin Bieber’s manager, Scooter Braun, and that connection led to a meeting with Def Jam in New York and Atlantic Records in Los Angeles during freshman year. When Harlow learned he’d be going to a meeting at Braun’s home in the Hollywood Hills, he said, “I’m kind of surprised it took that long.” Braun’s place had a basketball court, swimming pool, koi pond. “Biggest house I’ve ever been in,” Harlow says. “He had like original Warhols on his walls.” Braun painted the scene: For Harlow’s public debut, he would come out during the middle of another rapper’s show looking lost. The crowd will start mocking the way you look, and then you’ll drop the heat! “He was saying this about my son, and my body was generating chemicals I can’t even explain to you. It wasn’t even adrenaline. I was squirming in my chair thinking, This is happening,” Maggie says. “I literally can picture the room and put myself back in that moment.”

That meeting didn’t lead to any offers, but the one in New York with Def Jam president Joie Manda did. But while Harlow and his parents were still debating and negotiating the offer, Manda left the label. Without him there, the Harlows weren’t sure if anybody at Def Jam would fight for Jack.

“At the time, I felt like it was the worst thing that happened,” Harlow says. “But looking back, I would have been a novelty locked into a five-album deal. I was still doing the funny-and-nerdy thing. At 14, I hadn’t developed as an artist or a person. It would have stunted my growth.”

“Jack was taken to the brink and then it all disappeared,” Maggie says. “It helped him realize it’s not gonna fall in his lap.”

After six months on Berry Boulevard, Harlow moves to Germantown, into a two-story house purchased by his grandmother, who owns rental property. “Just a better situation all around,” he says. “My grandma is the clutch-est.” The front room’s wood-paneled wallpaper features deer and seagulls and game birds. “You know Santa Fe Grill near U of L? Same wallpaper!” Harlow says. Craighead’s room is on the main floor, and Harlow and Garvey — “Harlow featuring Cope” — have bedrooms upstairs. On the carpet in Harlow’s room is the mattress he used to sleep on in his parents’ house. The Pittsburgh Steelers blanket is for his favorite football team, a passion passed down from his dad, who’s also the inspiration for his growing collection of country music T-shirts. The one from the 2007 Flip Flop Summer Tour stars Kenny Chesney and Brooks & Dunn. “Country is not necessarily my cup of tea, but the melodies are fire,” Harlow says. (“I guarantee he can’t name a Kenny Chesney song,” his dad says. Harlow: “He’s right.”)

Harlow is still deciding what to do with his narrow nook that has a window. “Just fill it with plush shit, maybe read a book,” he says. He mentions how he checked out a mystery called Murder at the MLA from the library because he liked the cover. It’s almost overdue. “I’ve read one page. It’s not very good,” he says. “But I’m trying to get back on my reading shit.” Right now he’s using the nook as storage for a few possessions: a watercolor his brother did of Outkast’s Stankonia album cover; a painting of the family dog, a Golden Retriever-poodle-Labrador mix named Raybo (“I wish he lived with me, but I don’t want to care for him like that”); an autographed copy of The Pursuit of Nappyness, by Kentucky hip-hop group Nappy Roots. He bought that CD at ear X-tacy during an album-release performance, his first-ever concert. “Now some of the guys in Nappy Roots are fans of me,” Harlow says of the Kentucky hip-hop group. “Crazy how it goes full circle.”

A black-and-white photo captures him onstage at Forecastle when he was 17, during a set by local producer/rapper Dr. Dundiff that showcased more than a dozen Louisville hip-hop artists. “Jack’s the only one from Louisville who could make it as a national rapper right now,” Dundiff says. Local entrepreneur/film producer Gill Holland put out the Handsome Harlow EP on his sonaBLAST! record label, and he says, “Before I worked in the film business, I thought the concept of star quality was BS. But the weird thing is, after you sit through hundreds of casting sessions and auditions and watch tapes, there are some people who, for some reason, just have that star quality. Jack has it. And he’s already had a great career and is only 19.” Chris Thomas, Harlow’s manager at Austin, Texas-based C3 Management, says, “Right now, we’re talking to labels, distributors, and figuring out how to grow the Private Garden collective.”

Early on, Harlow knew that some people would never be able to see past the fact that he’s a bespectacled white rapper with finger-in-the-socket ringlets. “I’m always going to look a certain way and can use that to my advantage, but I don’t want it to become a crutch or a gimmick. I just want it to be: ‘He makes good music,’” he says. (He declined to be on an MTV reality show about up-and-coming rappers. “I think I’d win but that’s not how I want to make it,” he says.) “I have to think about my image, especially with how superficial my generation is. I tell videographers to really capture how I look. Even me, I’m more likely to click a video of someone who looks interesting.”

Photo: Harlow onstage at Forecastle // John Miller

One day in the front room of the house, Harlow mentions that he goes to Salon Bacco on Bardstown Road. “If it’s in a salon, is it a barber?” he asks Craighead.

“You know I’m not gonna call it a barber,” says Craighead, who, like the rest of the Homies, gets his hair cut by 2fo.

“Well,” Harlow continues, “my mom put me on to this great dude, and he was like, ‘Listen, it doesn’t look like you’re going bald, but I know your dad is bald, I know your grandpa on your mom’s side is bald. You could go bald one day. So I’m gonna tell you this: You need to go ahead and get on this Rogaine wave now.’ I was like, ‘No shit?’ So I’m already putting Rogaine in this joint. I’m out here getting ahead of the curve. I’ll have girls come over and see that Rogaine and they’re like, ‘What the hell?’ I’m like, ‘Just know I’m on top of shit.’”

He wears the glasses because his lazy left eye is “trash as hell.” “It could probably get worse and get on some Forest Whitaker shit,” he says. He never used to want to be seen without his glasses, which have become a staple. “But I don’t want to show up to a show and have a promoter say, ‘Whoa, why aren’t you wearing them?’” When he doesn’t have them on, he puts a contact lens in the left eye. And he’s been wearing a new pair of black frames. “They look like I know I have glasses on, as opposed to before when it looked like I had to wear glasses for my eyesight, which was in fact the case,” he says. “Now that I think about it, maybe that’s not such a cool switch. Luckily I haven’t blown up to the world yet, so my impression isn’t made. But I can’t decide how I want to look.”

Or how he wants to sound. On one unreleased song, “Too Much,” Harlow sings in a high register that — well, he doesn’t even seem like the same person who once rapped, “I’m an aggravatin’, masturbatin’ rap sensation with the swagger of a premature ejaculation.” It sounds so unlike anything he’s released that, even after hearing it more than 10 times in the studio, I ask, “Wait, who is that singing?” “I’ve tried to narrow my scope to make almost everything I write profound,” he says. To him, every line in “Too Much” is a metaphor for his life. The opening couplet is, “She say that I tell her that she pretty too much. I grew into them skinnies used to rock them bootcuts.”

“There is a girl that didn’t want me back because I was almost too nice to her. She likes assholes, she historically has, and that line encapsulates that situation for me perfectly,” Harlow says. “And then that second line, I dead-ass used to rock goddamn mom jeans, so I got some thinner jeans that look better on my frame. But the metaphor in that is, ‘Damn, he grew up.’”

Harlow says he’s sitting on about 10 songs that he’ll put out. Or maybe not. Last September, for instance, he spent half a day polishing two tracks at Head First, a studio in a former church in the Shelby Park neighborhood. Harlow said one of the beats reminded him of walking outside in the morning, hair still wet from the shower, sun shining. He rapped about how “my girl the same age as my ACT — 27.” And about having “a couple issues with driving”: speeding ticket, skipping traffic school, suspended license, totaled car, skyrocketing insurance. (It’s probably worth mentioning that, when Harlow was heading to Qdoba before the Thanksgiving Eve show, he performed a 25-point turn maneuvering out of the parking lot at Headliners.) The engineer burned the tracks onto a CD because Harlow thought they should listen to them in the car. He cranked up the volume. “Whoo!” he shouted. “That shit is flawless!” Never released.

Harlow doesn’t really like the 18 cover art anymore, the one of him in his underwear. Or the “Ice Cream” video. He has taken a lot of his music and many videos off the internet because he’s afraid his past work will diminish his credibility. “Sometimes I want to take all of it offline,” he says. “Even the shit I’m making now I probably won’t like in a year.” He used to always keep a rap he’d written — four lines, eight bars, never a whole song — folded in his pocket at all times, one that he still considered perfect. “I would be so scared to add to it and ruin it,” he says. “That dynamic has moved with me as I’ve gotten older. I’d be happy for a moment. It was almost like I had everything on my end taken care of internally. But that feeling is temporary.” He’d read the rap the following day, then again the next. Eventually, he didn’t think it was good anymore. “It’s like looking at a car. It won’t look dirty, but then I get up close and see specks of dirt,” Harlow says. “I’d have to find something new to write to keep with me.” Harlow never recorded those raps, though his parents found about 50 of them in a box when he moved out.

Photo: Jack Harlow // Mickie Winters

Matthew Rhinehart was Harlow’s English teacher junior year, and he remembers Harlow liking Hunger, a book from 1890 about a man who suffers for his art. “It was about how art is a full expression of one’s individuality and how you don’t compromise on that,” Rhinehart says. “That really resonated with Jack.”

Harlow’s mom studied oil painting in college, and she says her son, as a painter, would be a super-realist, obsessing over every detail. The cover illustration for the “Routine” single is a bird’s-eye view of a sleeping girl and a wide-awake Harlow on his mattress, with Raybo, a pair of New Balances, a Spinelli’s pizza box and a “Private Garden” book on the floor. His glasses and charging phone are on the nightstand. “I pick apart the things that nobody else is really gonna see,” Harlow says. “It might be one word in a song. I wish I could make masterpieces quicker.

“I’ve heard about monks who would spend a whole day on art and destroy it at the end of the day no matter what it was. That slowly detached them from what they were creating. Sometimes it’s so hard for me because I start creating something and as soon as I start liking it, it becomes very precious to me.”

On his mattress, Harlow will flip his iPhone to “airplane mode” and write in the Notes app, on a screen that shattered when moisture from the shower built up and caused the phone to slip off the windowsill. “I wanted to stay true to the paper, bro, but it’s tragically inconvenient compared to the phone,” he says. Plus, you need a light on to write on paper, and Harlow prefers to create in the dark. He’ll get a beat from the Homies and will listen without headphones — “For hours and hours and hours and hours,” Craighead says. He still makes sure the beat is loud enough to shake walls. “Just hitting me in the face,” Harlow says. “It has to be loud enough to cover my voice.” He likes to rap out loud, to mesh with the beat, but doesn’t want anybody else to hear what he’s saying until he’s ready to record. “When it’s not coming it feels like work, like: Do I even love this anymore?” he says. “But when I’m in the zone, I’ll start rocking back and forth like I’m going crazy or something. It’s a euphoric feeling I can’t step away from. I’m not even necessarily a third-eye kind of person, but there’s something spiritual about it.”

When I ask him to show me some of his notes, he says, “This is a very personal space.” He scrolls so fast it’s as if he doesn’t want me to see. The only words I catch are: “That junk food give me love handles for the summer.” He says he’ll send me some examples later, but when I remind him, he texts: “I don’t think I can. I didn’t even really like showing you at the house or when you wrote down that one example. A big part of the art for me is choosing what I release to the world.” I ask him if he can tell me how many individual notes there are. Six hundred and one.

The basement studio is also called the Private Garden, where one of the books on his mom’s old cow-print coffee table is Private Gardens of Paris. The whole concept for the name came to Harlow during a film-studies class his senior year, while learning about the Japanese director/animator Hayao Miyazaki. One of the settings in Howl’s Moving Castle is a secret garden. “I was kind of half-watching and that scene came on,” Harlow says. “I’ve always liked garden-ass shit: gazebos, benches, things that people built that are overlooked daily and might not get used.”

The basement carpet is the same color and thickness as the fringe of a golf green. Wood paneling encases the walls and even some of the window wells. The beanbag is Shloob’s. The guys use an Akai MPK49 performance keyboard — “Aka professional,” Harlow says — to concoct beats. Speakers flank a desk, on which stands a tiny resin garden fountain Harlow’s mom used as a cake-topper for his 19th birthday. A storage closet is now a recording booth with exposed insulation in the ceiling, walls of sound-proofing foam that looks like egg cartons, headphones hanging from a hook and a microphone stand. Harlow is six-foot-three and has to duck under the ductwork when entering.

Photo: Harlow at Forecastle // John Miller

2fo is always in a trance tweaking beats at the computer, the top of the headphones hiding in his afro. Shloob operates a sewing machine with a foot pedal, tailoring a thrift-store pair of black-and-white floral women’s pants for Garvey. Craighead gets home late from work at Cricket Wireless and tells a story about how he was looking at his phone and ran a red light and almost died. “Damn,” Harlow says, “you’re a real menace to society.” O’Bannon says, “I just got a job.” Doing what? “I think it’s like insurance?” Harlow mentions how he opened a box of Little Debbie Donut Sticks at Kroger, took one out and hid the evidence. “You can grab a chocolate milk, finish it, throw it away, and walk out,” he says.

Garvey: “You could do that with any food in Kroger and not get caught.”

Shloob: “You could eat a whole dinner.”

Harlow: “And that shit’s on the record!”

The guys execute a complex handshake that includes finger snaps. “Y’all look like a damn NBA team,” Nemo Achida, a Lexington rapper in his late 20s, says. When Achida goes on a back-in-my-day tangent, Harlow says, “So what you’re saying is, the youth is taking over.” (Achida is featured on the song “Obsessed,” off 18. “One thing that I thought was dope — that nobody had done to me before — is Jack made me re-write my verse,” he says.)

Harlow has been trying to suppress his debilitating perfectionism by creating down here “in the moment” — if those words can mean a session that stretches from 8 p.m. until the slap-happy stage of fatigue at 4 in the morning. The beat loops for so long that it somehow becomes white noise. Harlow has turned off the “damn cafeteria” fluorescent lights. The lamp bulbs cycle through colors — blue, red, purple, green. Phone in hand, Harlow writes while leaning against the basement support pole, sitting on the carpeted stairs, sprawling on a love seat. His hair dangles like Spanish moss as he hunches over, the screen’s rectangular glow reflecting in his glasses. He mouths the word puzzle connecting in his brain. When he makes eye contact, it’s clear his mind is somewhere far away. Then: “All right, let’s go.” He heads toward the booth. “I’m still me when I’m in there,” Harlow says. “I’m just homing in on different zones of my personality.” Tonight he’s doing a 45-second verse that begins with him rapping, “This the shit I ride around to when nobody text back. I call this shit my jam like it’s strawberry extract.”

“One more time,” Harlow tells 2fo, who’s at the computer recording.

Take two.

“Damn, ran out of breath on that one.”

Take three.

“Run it back.”

“I got it this time.”

“OK, start it from the top.”

2fo says, “Sometimes only Jack can hear what Jack hears.”

“I’ve been more scatterbrained than ever lately,” Harlow says one spring afternoon in his house. “It’s like I have late-onset ADD or something.” He blames phones. “They’ve become part of our bodies,” he says. His mom told him to try meditating.

Harlow says he likes driving without using GPS. “My dad talks about the fact that his generation knows where the hell they’re going in Louisville much better than mine because they weren’t looking down at a screen their whole childhood,” he says. “Sometimes I’ll look in the car and I’ll have three guys with me and they’ll all be on their phones. That feels normal at this point. But there’s something to be said for looking out the window.

“I’m not on some hippie shit,” he says, “but I really crave having conversations with people.”

Photo: Harlow at Forecastle // Urban Wyatt

Harlow can improvise a 10-minute soliloquy on anything.

Furniture: “I’m not exactly into interior designing, but I’m definitely into how convenient you can make a room. My dad and I make fun of my mom’s side of the family because, yeah, they might have a lot of seating but they don’t understand airflow.”

Cleaning: “Something about everything being in order is so therapeutic. I love wiping shit down with Clorox wipes. Taking out the trash gives me such satisfaction.”

Movies: Life Is Beautiful: “That shit is fire.” The Prestige. “Dope. Fire.” Moonrise Kingdom. “That shit was ass to me.” Y Tu Mamá También. “It explores the Oedipus complex, which was intriguing to me because I like older women.”

Older women: He tweets that he wants Meryl Streep to adopt him. His Instagram includes a photo of Marisa Tomei (caption: “i really shouldn’t keep puttin’ y’all on to all the middle aged actresses i want to make children with”) and a photo of one of his elementary school teachers (caption: “this is where the fantasies began”). “Oh, I’m obsessed with older women.” What age range? “I mean, there’s really not a limit on it. As long as they’re somewhat attractive, it could go into 50s. Sixty’s a bit much.” Has he had success? “The oldest I’ve had true success with is about six years older than me. There’s this one woman, I was going over to her apartment and drinking tea and she’s 38. As soon as I started talking about sex, she said she didn’t know if she was ready. She always talked about how on my 20th birthday she would.” How’d he meet a 38-year-old? “I was at a listening party for — shit, I don’t know if I should tell you all this!”

Love: “I’m excited to be madly in love with somebody. I think that’ll be real tight.”

Fatherhood: “If it’s not music, it’s hard for me to always feel like I’ve got this purpose. And I feel like having a kid will give me this immediate purpose. I like to teach people things. I like seeing growth in general — in myself, in other people. I would take so much pride in being a father. I think I’d be a dope dad.”

Food: “Copelan introduced me to toast. Just jelly and butter.” Cheese pizza, no toppings. “Ketchup is the one condiment I love.” Jimmy John’s order: the Slim #1, which is ham and provolone on French bread. “I eat so much fast food. I get it from my dad. I’m addicted to sugar, fat, carbs — all that. Some people don’t think it’s a vice, but it will kill you too. That’s why I don’t smoke or drink or anything.”

The day of his Headliners show, Harlow was at the twins’ house near Churchill Downs and noticed a small glass bottle on the coffee table.

“Can I hit that?” he asked

“You don’t want to hit that,” Shloob said.

“It’s not cologne?”

Shloob shook his head. It was a small bottle of bourbon.

“My dad’s actually never been drunk because his dad passed away from alcoholism, so he had no interest in it and it’s not like I was around drinking a lot,” Harlow says. “And I see people get shitfaced and it doesn’t look appealing to me.”

On “Hitchcock,” he raps, “I’m moving with a pack of kids and supervising acid trips,” and when I ask him about that lyric, he says he’s taken the drug twice. The second time wasn’t planned. He saw his friends in the bathroom, they asked him if he wanted some and he put a tab on his tongue. It led to what he describes as “the most euphoric moment of creation that I’ve had.” He was sweaty, his heart pumping. “To me it’s like being high on weed but to a way harder extreme,” he says. It’s an unreleased track he doesn’t want to name in this story, but that night in the Garden he and his friends danced and jumped to what Harlow believed was, for the first time, a song he’d made that they’d actually listen to riding around in the car. “Seeing my friends’ reaction, for me that was really validating,” he says.

“But after that moment I was so scared to do that again. It’s easy to see why artists get into substance abuse because of the incredible shit you will create, but you probably get to a point where you don’t even believe in yourself sober and then die from an overdose 10 years down the road,” he says. “The acid took me somewhere else. We came up with concepts that I never would have come up with sober probably. And that’s special. But that’s why I don’t like doing drugs. I’m scared to not be able to create or be happy without them. And they can make you happy as hell. People tiptoe around the word happy with drugs.

“It’s scary for me to think about something making you happy like that so often that you can’t even feel happiness naturally, which is my life goal. I’m not about to skip levels and try to get there with some drugs because I know it won’t be real.”

He says he’s happiest after he makes something “perfect and profound.” “When I feel like I actually made art,” he says. “In that moment, you feel like you’re doing exactly what you’re supposed to do on this earth. You almost feel like everything about you — even your flaws — is perfect. It’s pure bliss. Ten times better than sex.”

Harlow has been traveling a lot more lately to Bass Recording, an Atlanta studio owned by Lexington native Finis “KY” White, who works with big names like Lil Wayne and 2 Chainz. Instead of his bedroom, Harlow will go to the parking lot to write alone in his car for hours. “Everybody has their way of doing it,” White says. White is almost always the last one to leave, but sometimes Harlow and his friends are up so late that he just says, “Y’all stay.” On one recent trip, Harlow and his friends slept at the studio. “KY gets in late, so if we sleep there we have the studio all day and don’t have to wait for him,” Harlow says.

Harlow has been considering moving to Atlanta, possibly using his parents’ connections through their Signarama business to get him a job down there to cover rent. “I think I’ll live in other places in my life. In terms of where I lay up and just sit in the sun, I’d like to live in Florida or L.A.,” Harlow says. “But I’d like to start a family here.” Wyatt says he’d move with Harlow to Atlanta, but even if they stay in Louisville, Wyatt is not going back for his sophomore year at the University of Cincinnati. “The time to try it is now, while I’m young,” Wyatt says. “I’ll go back if I fail — but I don’t talk about that.” Harlow doesn’t either. “When I wake up in the morning, music is what I’m thinking of,” he says. “It’s almost like having a child. Maybe not as strong as that but, if you have a child, even if you’re not literally thinking of them, I’m sure it’s always there in the back of your head. Music never leaves me. If I go out to a party I might be focusing on something else but in the back of my head my priority is music. With it being like that, I feel like there’s no way I can’t make it happen for myself.”

Harlow knows his parents wanted him to go to college. “I can’t blame them for not expecting to have a rapper as a son,” he says. “But I found my purpose.”

His dad says, “The jury’s still out, but we’ve told him, ‘Let’s see what happens the next four years of your life.’” Maggie says, “You don’t realize your kid is gonna send a meteor into your life. I kind of had to talk myself off the ledge — OK, he’s not going to college — but why shouldn’t he pursue his dream?”

Each month Harlow gets a check from streaming services like Spotify, and he gets paid for live shows, but it’s not enough money to make a living off music yet. He does say he’s finally getting closer to wanting to make a cohesive album, as opposed to the less-formal mixtapes he has released so far. “Everyone is kind of waiting for him to make his next move,” his manager says.

In mid-June, Harlow is in the Garden again, shirt off, his shoulders red from Bonnaroo. He’s been lifting weights with Wyatt this summer, his muscles becoming more defined. While 2fo’s in a beat trance, Harlow plays some of his old material on the computer. “Some of this shit is goofy,” he says. “It definitely makes me tense up a bit.” During one verse on “Family Vacation,” from junior year, he says, “I’m not the type to play. Unless I got the part. L-O-L, that’s a joke I came up with.” “God,” Harlow says. The chorus, though, is “lightweight genius”: “But I know it’s all gonna be nostalgia soon, and when I look back I can say I caught it too.” On the final verse he says “cash running low like the end of my name” and rhymes “larger” with “Founding Fathers.” “I came out of my body on that bitch,” he says.

“You can hear my voice changing over the years,” he says. “I sound like Simba growing into himself.”

In a month he’ll be under a canopy backstage at Waterfront Park, waiting for his Saturday afternoon set at Forecastle. He’ll eat catered fried chicken and corn on the cob and this “cobbler-type shit that’s fire.” He’ll say, “This is the most lavish I’ve ever lived.” As the crowd chants his name, he’ll prowl behind the stage and bounce in place like a prizefighter. Toward the end of his set, Harlow will perform “Ridin’ Round Town” and rap, “Lookin’ for that thing that gon’ change my life, lookin’ for that thing that gon’ change my life. Man, that shit so real had to say that twice.” That song came out in 2015 but he’s been saying it for as long as he can remember.

But right now, in the Garden, 2fo’s beat is ready. And so is Harlow’s chorus:

“It’s that wasted youth.

Killing time.

Say the truth.

Feel the vibe.”

The bulb in the booth is shining bright white. Harlow takes a quick swig of water from a gallon jug. Then he walks toward the light and shuts the door behind him. He steps up to the microphone. “I’m ready.”

This story originally appeared in the August 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find your very own copy of Louisville Magazine, click here.

Cover Photo: Jack Harlow onstage at Forecastle // John Miller