By Sean Patrick Hill

Photos by Terrence Humphrey

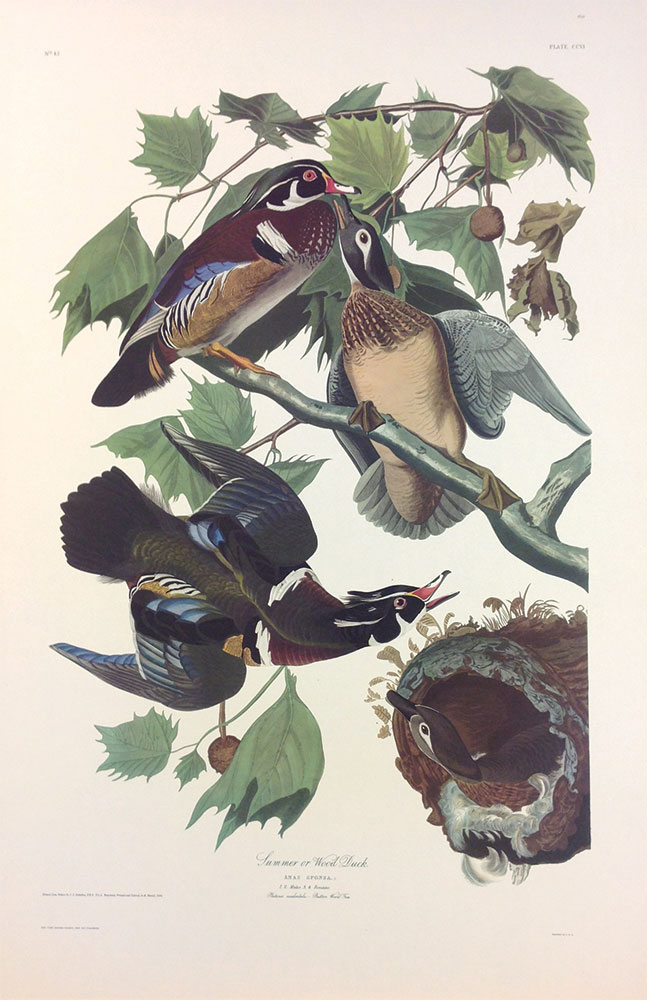

I came upon the Audubon print in a Mellwood Avenue antique store this past summer. Its frame leaned against a wooden chair between a walnut huntboard and a mahogany bureau, beneath various chandeliers, and I immediately recognized, even from a distance, Audubon’s elegant style of graceful forms composed of flowing watercolors. The print of wood ducks measured some 15 inches by 18 inches. Four birds, two males and two females, were set against the backdrop of a sycamore tree. A pair perched on a limb, one curved in flight and a female in the lower-right portion lay half-hidden in a hollow log, nested on a bed of white feathers.

The frame was clearly old, the wood painted gold. The paper backing, cracked and brittle and marked with a sticker for the framer — Frank J. Bimmerle Picture Frames — flaked at a touch. I looked closely at the writing along the print’s edges: Drawn from Nature by J.J. Audubon. Plate CCVI, No. 42. Engraved, Printed, & Coloured by R. Havell, 1834 — the English spelling, I later learned, indicated its origin in London. The print’s quality astounded me. I began to pace, thinking I’d chanced upon an authentic Audubon. I used my phone to get as much information as I could. One of the first pages I found for “Summer or Wood Duck” was the auction house Christie’s, where an original Havell edition sold in 2011 for $25,000.

The frame was clearly old, the wood painted gold. The paper backing, cracked and brittle and marked with a sticker for the framer — Frank J. Bimmerle Picture Frames — flaked at a touch. I looked closely at the writing along the print’s edges: Drawn from Nature by J.J. Audubon. Plate CCVI, No. 42. Engraved, Printed, & Coloured by R. Havell, 1834 — the English spelling, I later learned, indicated its origin in London. The print’s quality astounded me. I began to pace, thinking I’d chanced upon an authentic Audubon. I used my phone to get as much information as I could. One of the first pages I found for “Summer or Wood Duck” was the auction house Christie’s, where an original Havell edition sold in 2011 for $25,000.

The price tag on the frame was 1 percent of that, a mere $250. Not an insignificant sum for me, but I bought it anyway, being assured at the very least it was rare. I gingerly carried it to the cashier’s counter. Outside, at the edge of the gravel lot, the water of the Muddy Fork, where one might imagine wood ducks floating beneath the cottonwoods, joined the South Fork of Beargrass Creek and flowed north beneath the interstate toward the Ohio River. I set the frame gently in the trunk and drove carefully, as if I were transporting a treasure.

At home, I began research into the print and quickly discovered it was not, in fact, authentic. Near the bottom of the paper, along the mat’s edge, tiny print read: Original, courtesy of Harry Shaw Newman, The Old Print Shop, New York, N.Y. This phrase, according to a rare prints conservator, was the most obvious clue as to its being a much later copy, aside from its dimensions — Audubon painted each bird life-size — and its lack of a watermark on the paper. The print, the conservator reported rather flatly, was of no great value.

Naturally, I felt foolish. The last thing I needed was an unnecessary expense on an item whose receipt said that all sales were final. But I was enamored with it all the same. The rich coloring and the precision of its lines showed care, even excellence. The paper seemed textured, as if handmade. I set out to learn more about it. How old was it, for instance? The flaking paper attested to its being an antique, and the aged sticker of Bimmerle’s frame shop, in blue and gold, only confirmed it.

I wrote the Old Print Shop in New York, from which the print apparently originated. The shop was still in business after nearly a century and a quarter. I asked about the print, its value, its age. The next day I received a reply from Robert K. Newman, grandson of Harry Shaw Newman. “Actually, my grandfather had nothing to do with this,” he wrote. “The prints were sold to Northwest Mutual Life Insurance Company, and they reproduced them from 1937 to 1941 and gave them to policyholders. Why they put ‘Courtesy of Harry Shaw Newman’ no one around here knows.

“To me they are just reproductions, and I do not feel that reproductions have any value. That being said, eBay has proven that everything has value.”

The tone was terse and discouraging, yet my interest didn’t flag. As far as I could tell, the image was not merely a cheap reproduction, despite the fact that eBay revealed that at least one of the same prints, unframed, sold for only $12.95. But the precision of the printing suggested it was an offset lithograph, the most ubiquitous poster-making process of the early 20th century. That alone set it apart from the posters of my day, the kinds of things a high school kid would buy at the mall and hang in his bedroom. What seemed an obvious point of research was in the framer, Frank J. Bimmerle. His shop on Pope Street placed him in the Clifton neighborhood, perhaps as far back, I imagined, as when the streetcars still ran up Frankfort Avenue.

I drove the print to the framing shop in Northfield I frequent and asked the owner, Brenda Russo, to replace the backing paper. I told her I wanted to keep the sticker.

“Well, we haven’t seen a Bimmerle in a while,” she said.

She told me that, at a glance, the print was faded, as was the matboard. “Look at the edging of the mat,” she said. “It should be white. All these specks on the print are not part of the paper itself, but pieces of the matting. It’s deteriorating.” She said it was a beautiful print regardless and suggested that I replace the glass to protect it from the sunlight, perhaps even having the print itself restored.

I told her that I’d recently learned it had little value. She said you never knew what a thing would be worth in 10 years, or 20. “As long as I’m taking the paper off, do you want to have a look at the print?” she asked. She tore away the backing paper, setting the sticker aside. Small nails held the matboard in place. I was glancing around the shop, examining the shadow boxes, as she pulled the nails out, one by one. “Oh, no,” she said. She held the matboard in her hands. “They glued the print to the mat. That’s just what they did in those days. There’s nothing I can do about it.”

While she cleaned the glass and lowered the print back into the frame, she told me that one of Frank Bimmerle’s descendants had recently come into the shop, and that she told stories about the old Bimmerle shop on Pope Street. I asked if she had the woman’s name. She said she was sorry, she didn’t. She re-papered the frame with a black sheet. When I left, she told me to look up a Facebook group on Louisville history called “Back in the Good Old Days.” Perhaps I could find a name there.

I hung the print in my living room, near the window. I examined it. The wood duck, also known as the Carolina duck, is one of the most colorful birds of North America. “The great beauty and neatness of their apparel, and the grace of their motions, always afford pleasure to the observer,” wrote the artist and ornithologist John James Audubon, who spent 12 years in Kentucky (two of them in Louisville) in the early 1800s.

The wood duck is a perching bird with strong claws. Though they are native to Kentucky, I’d never seen one here. Audubon clearly did. “Summer or Wood Duck” is Plate 206 in the original edition of his Birds of America, printed between 1827 and 1838. The wood ducks, Audubon wrote, “have afforded me hours of the never-failing delight resulting from the contemplation of their character.” He wrote of seeing them in Kentucky in “flocks of from thirty to fifty or more individuals.”

They paired, he observed, around the first of March, when the dogwoods bloom. He painted them in the sycamore where he often saw them nested, a tree that grows always near the water. Once, he found a nest of 10 eggs on the Kentucky River. Another time, when a female left her nest, he saw that feathers — including those from other birds — covered the eggs.

Audubon learned to catch the wood ducks in a bag net, or with his pointer dog. He became adept at concealing himself in the marshes so that he could “shoot them on the wing.” By the time my print was framed, probably prior to Pearl Harbor, the wood duck had been hunted nearly to extinction.

A Courier-Journal article, dated Aug. 14, 1972, shows 79-year-old Frank Bimmerle, his face stern behind horn-rimmed glasses, wearing a blue apron over a shirt and tie. The caption reads, “He’s not about to change after 63 years.” Behind him, frame samples hang on the wall. A worktable glows white.

The story recounts Bimmerle’s history. Born in Louisville in 1893, he began working for his uncle at age 16. The young Frank lived with this uncle, the photographer George F. Martin, in the house on Pope Street, framing photos in a back room. When his uncle died in 1922, Bimmerle began his own framing business in the house. At the time, there was perhaps only one other picture framer in the city of Louisville. An 11-by-14-inch frame cost 65 cents. Bimmerle, in time, employed as many as 20 people. For extra money, he played flute in theater orchestras.

Twice a year, Bimmerle would ride the streetcar throughout the city, showing off frame samples. His customers — from everyday people to colleges to corporations — chose from 500 frame patterns and 150 different matboards. Bimmerle sustained his work on reputation alone. He did not advertise, and, though he built onto the original house to improve the shop, he refused to expand. By the time of the article, his wife had been dead for 15 years, and his two sons, Paul and Joseph, worked with him. He died on Aug. 23, 1980, at the age of 87.

One day during my lunch hour, I drove to Clifton to find the house, a shotgun about a block and a half beyond the Hilltop Tavern. It sat on a small rise, above a limestone retaining wall. I crossed the street to the crumbled curb and the cracked sidewalk and climbed the steps between the iron railings. The house was entirely nondescript, plain behind its red-brick porch. I went to the front door and knocked and waited. An ashtray and empty beer can rested on a tabletop. When no answer came, I walked along the side of the house to the side door. I knocked again. I took a bit of paper from the car and scrawled a note to the occupant, asking for a phone call if they knew anything about the house being a former frame shop. I left it in the mailbox but never heard back.

At home, I pored over newspaper archives. The obituary for Frank Bimmerle indicated he had both a grandchild and great-grandchild. One of them, I knew, was the woman who came into the frame shop in Northfield.

On March 6, 1988, in the Sunday edition, the Courier-Journal published a story about Frank’s son Paul. By that time, there were more than 160 picture framers in Louisville. To that fact, the 68-year-old Paul Bimmerle said, “There are too damn many. There’s a super-saturated solution of picture framers, and they’re kidding themselves.” He was still operating the shop on the second floor of the house on Pope Street, which by then was joined to the house next door. Despite having had cancer three years prior, he worked five days a week.

By the time of the article, Paul said his clients were literally dying off. Like his father, Paul didn’t advertise. In time, the business was sold and later shuttered, after Paul died in the winter of 1991. I discovered that Paul had a son who died at four months old on a Sunday evening, in the early summer of 1949. He died in the house that Paul lived in on Pope Street. The child, Mark, was buried in Cave Hill Cemetery.

Photo: The house on Pope Street where Bimmerle ran his framing shop.

On a Tuesday afternoon, after a morning of rain, I drove to Cave Hill. I followed the curving main road to the office, where I asked for help finding the grave of Mark Stuart Bimmerle. The man searched on a computer and on a sticky note wrote: Section 19, Lot 363, Grave 1. He brought out a map of the section, peered over it with a magnifying glass and circled the grave. I drove the avenue to a far edge of the cemetery and parked along a row of cherry dogwoods. I walked upslope toward the second row and found Paul and his wife, Edna Mae Ferguson. Around the backside of the grave, I found the name of their son. In the distance, I heard the mowers. I smelled the cut grass.

At home, I followed the thread of obituaries from Paul to his wife and found the name of their daughter, Paula Bishop. I found her phone number online and called her.

I met Paula Bishop at the Panera Bread in Northfield. She carried a large bag of photo albums, frames, artifacts. Bishop, who has taught in Cincinnati, Owensboro and Louisville, including at Sacred Heart Academy for 25 years, bought tea and took a table in the back.

She showed me a clipping from International Musician, a journal of the American Federation of Musicians. The photograph was taken in St. Louis in 1913 and mounted on a board with wheat paste that her grandfather, Frank Bimmerle, stirred himself — the same paste, she thought, that was undoubtedly used on my Audubon print. The photo showed her grandfather standing with his flute among a uniformed band from Louisville. The group had put on a concert at the old Fontaine Ferry amusement park in west Louisville and raised $200 for a fund for “the families of the ill-fated Titanic musicians.”

She leafed through frames: her grandparents’ wedding photo, a framed and hand-painted family portrait and a 1941 shot of the men, including her father, working in the shop. She showed me pictures of her father Paul in uniform — he served in World War II as a medic in Italy and North Africa. She showed me a letter her father wrote as a child from St. Joseph’s School to his own father. The song “The End of the Innocence” played from a speaker.

“I remember my grandfather as a very straight-laced, religious, not-warm-and-huggy kind of person,” Bishop said. “Part of it was how he was raised. He had a German background, and I think a lot of German people keep their personal life personal, and their business life as a different thing.” He kept records of everything, she explained, including any gift he ever gave or received. “I never remember him without a pair of dress pants, a vest or a sweater when it was cold, a sport jacket over it with a shirt and a tie. He was always dressed like that, even when it was hot.”

In the shop on Pope Street, a housekeeper would make meals, and the workers ate in the dining room. Bishop said her grandfather did payroll on Fridays and paid his employees after lunch. He would go to Stock Yards Bank with scraps of matboard, on which he had written everybody’s hours. “He’d go down to the bank and get all that in cash,” Bishop said.

I thought about how if someone in an antique store found a Bimmerle frame as I had done, the sticker with that family name would likely mean nothing to them. I asked Bishop what she thought about this vanishing history. After a moment she said, “I guess I never really thought of it that way.” She said she instead thinks about the personal service her family gave the customers. She explained how the workers carefully brushed the wheat paste to hold a piece down, flattening it thoroughly before framing. Even if it was not considered “museum quality” like my own Audubon print, they nevertheless did a fine job.

“My grandfather was very old-fashioned and stuck in his ways,” Bishop said. “The frame shop went the plight of any other small businessman who tries to compete with big-box stores. Times changed. They didn’t have the manpower and the capital behind them to start something like Michaels. So the business went the way of other craftsmen that do small-batch things.”

I thanked her for her time and mentioned how disappointed I was that I hadn’t brought my frame. It was OK, she said. She’d seen many frames.

“Have you ever seen a wood duck?” I asked her.

She hadn’t. I told her that after I visited the graves at Cave Hill, I drove down to the lake and saw what looked like wood ducks. One male, its eye blood-red, stood on the toe rocks. A band of females stood up from the grass and walked along the shore and out of sight. I crept down the hillside, shielding myself behind the old white oaks, toward the one male left on the shore. Almost to the edge, I saw ripples on the water. When I stepped out from behind the trunk, I saw in one exploding moment the wood duck, its red eye fixed on me, before it burst into flight and disappeared over the lake.

This originally appeared in the December 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find us on newsstands, click here.

Cover: The Audobon print "Summer or Wood Duck," and detail of the frame and notation.