Photos by Mickie Winters

Since Friday, Louisville has seen four homicides and a six-year-old shot by stray gunfire. "I mean, here we are again,” Lt. Emily McKinley with LMPD’s homicide unit said during a Tuesday press conference. "We need to nip this in the bud now. I don't want another 2016 record number of homicides." In our February cover story, we take a look inside Louisville’s surge in gun violence.

A gentle rain tricks the warning lights from police cruisers into a festive spirit, wet cars and streets catching the red and blue as sparkle. A homicide detective pulls up in his SUV, parking near a home draped in twinkling holiday lights. It is New Year’s Eve, less than one hour left in 2016. All around the Portland neighborhood gunshots pop. Tat tat tat tat tat tat tat tat tat. “Jesus Christ,” an officer moans as shots fire somewhere nearby, then farther away and then so close I gasp and rattle. All night, dispatch has received calls of gunfire — 28th and Kentucky streets, the 1500 block of Highland Avenue, 1000 block of Magazine Street. Celebratory New Year’s gunfire isn’t just a Louisville tradition. All over the world, guns aim at the night sky.

But here in Portland, at just after 10:30, an accident. A stray bullet grazed a chubby-cheeked brunette toddler in the shoulder as he was being loaded into his car seat. One minute he’s heading home with his mom. The next, rushed to the hospital. News photographers and reporters wait for an update on his condition behind cameras and tripods. Tat tat tat tat tat tat tat, more rounds into the air.

A man in a ball cap standing on a lawn talks into his phone: “Hey, buddy, what are you doing? You hanging tough for mommy?” he says. “Daddy will be there soon.” On New Year’s Day, the boy’s father will post an image on Facebook of his son lying in a hospital bed, a bandage on his shoulder, with a message: “...this is what happens when dumb people decide to shoot their guns off on new year’s…”

Tonight’s shooting is indeed an accident. But the last two years, especially last year, guns were drawn with the intent to kill. As of the last day of 2016, Louisville had seen 117 murders, nearly all of them the result of gunshot wounds. In mid-January, that 117 got bumped to 118 because a 14-year-old died who had been shot on Christmas Day at 21st and Market streets. That total — 118 — is the most the city has seen since 1960 when authorities started keeping record. (The previous record was 110 in 1971.)

Since Louisville Metro incorporated in the early 2000s, homicide totals usually swung in a range of 50 to 70. In 2015, a jump — 80 murders. Then 2016 — a 47 percent increase in one year. (If you add six homicides that occurred outside Louisville Metro’s jurisdiction but inside Jefferson County, the total is 124.) Of the homicide victims, more than 60 percent were black. (African-Americans make up about 23 percent of the population.) More than half of the victims were younger than 25. More than half were black males. The homicides stacked up steadily, seemingly every few days. With warm weather, intense bursts. In August, there were seven shooting deaths in one week, only one of which was determined a justified killing.

It’s a year in which a veteran JCPS teacher counted 12 of her former students killed by gun violence in 12 months. It’s a year in which a five-year-old watched the 51-year-old man he considered his father get shot and killed just before Christmas. It’s a year in which two teenage brothers were tortured, stabbed, burned and dumped by a 26-year-old (with the help of two juvenile sidekicks) who feared the brothers would rat on him for another murder. It’s a year remembered for a brutal drive-by shooting that took out a popular, football-loving 14-year-old named Troyvonte Hurt. Hurt’s friend allegedly aimed the bullet for the car firing at his crew on a Smoketown sidewalk; instead he accidentally shot his friend. Hurt’s brother was there in the chaos and watched as the kid they lovingly called “Fat Daddy” died. Fat Daddy’s friends — middle-schoolers, elementary-aged kids — got hit with his death on their phones after a flurry of social-media posts.

In 2016, LMPD recorded 407 fatal and nonfatal shootings, up from 356 in 2015 and 247 in 2014. The bold ones earned headlines and outrage, like when a 15-year-old unloaded his gun on two kids he was angry with at the Pegasus Parade, unfazed by the cops and families that lined Broadway. Louisville made national news on Thanksgiving, at the annual football competition known as the Juice Bowl in Shawnee Park. According to the Courier-Journal, a conflict that started over a prized dog breed escalated into a shooting that killed two and injured five, all while Mayor Greg Fischer stood a couple hundred yards away. Dozens of bystanders dropped to the ground, confused and shaken. Screams. “What the fuck is going on?”

But tonight, good news. Or, at least, fortunate news. The toddler will survive. “Thank God it’s not fatal,” his dad will write in a Facebook update. The boy is lucky. Several-inches lucky. “Bullets don’t cut. Bullets crush,” a University of Louisville trauma surgeon explains to me one afternoon. What they crush determines life or death, wheelchairs or walking, brain injury or live to tell. “It’s like real estate,” the surgeon says. “Location, location, location.”

The homicide detective drives off, no longer needed. Patrol units disappear into the wet dark. Assault rifles and pistols press on, a torrent, a salute to 2016, a greeting to the new year.

A news helicopter repeats tight loops overhead, a constant left turn that migrates over the downtown courthouse, police headquarters and Beecher Terrace housing complex a few blocks to the west. It’s Dec. 2, 2016, and at about 4 p.m. a call comes in to 911 — man shot, black male, Fisk Court inside Beecher Terrace.

This is murder 109. Number 108 occurred the day before, just before 3 p.m. at 12th and Hill streets in front of the Parkway Place housing complex. A drive-by. Puffs of dust exploded when bullets hit the sidewalk. They pierced 19-year-old Javon Johnson too. He went from walking confident to instant crumple in half a heartbeat. Silver and blue balloons and white stuffed animals now mark the spot.

Police lights reflect off Beecher Terrace’s stocky, barracks-style buildings that surround 27-year-old Wilson Burton. He lies face down on a grassy patch near Building 27. Crime-scene technicians diligently place green evidence markers next to about a half-dozen bullet casings scattered around Burton’s dreadlocks, black sweatshirt and jeans.

Behind the yellow police tape, a man in a white hooded sweatshirt throws a large Styrofoam cup to the ground, liquid slapping the pavement. “Damn, bro! Fuck!” he cries. “Just took him out!” His outburst echoes through courtyards. Officers’ heads swivel, looking for any signs that more gunfire might erupt. “This shit’s pathetic!” the man shouts. Residents who’ve bundled themselves under thick coats and clutch hot drinks hold their chatter, either nervous or compelled to respect such agony. Two or three minutes pass. The man’s grief softens as he walks away.

It’s been just over an hour since the homicide call came in, and detectives already have video on their phones of a black car with tinted windows driving past Burton, bullets spraying out. Video cameras hang bird’s-eye from poles on either end of the alley, a strip between buildings that’s seen two other homicides in the last few years.

Beecher Terrace is one of two public-housing projects built in the mid-1900s that’s still standing (though it’s slated for demolition and revitalization). It sits in the Russell neighborhood, which like other neighborhoods enduring high rates of violence — west Louisville neighborhoods California, Park Hill, Shawnee — faces incredible challenges. In Russell, 60 percent of residents live in poverty. Unemployment sits at about 30 percent. Violent crime is five times the citywide rate. A PBS Frontline documentary showed that one of every six adult Beecher Terrace residents cycles in and out of prison each year. Studies show that cities with long-term socioeconomic problems like racial segregation and poverty are prone to short-term spikes in crime. (Chicago had the worst 2016, totaling 762 homicide victims, a 57 percent increase over 2015.) And while violent crime has trended down nationwide over the last three decades, the 2016 murder rate rose by 14 percent in the nation’s 30 largest cities, according to year-end projections by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law.

Lt. Emily McKinley, who heads LMPD’s homicide unit, arrives on scene. After several years as a detective, the petite 32-year-old took over the homicide division in October, a time when the city was clearly on pace to break its homicide record. She became the face of the unit, the one reporters text at 9 a.m. for any news to break and the one who’s trotted out in front of cameras regularly. When you think of a homicide boss, she’s not the messenger you might expect — doe eyes, delicate features, young. But she’s serious and diligent. (She shares a story about getting a “C” on a math test in college and thinking it was the “worst thing ever,” so much so that she ditched her plans on an engineering degree.)

Lt. Emily McKinley, head of the LMPD's homicide unit

In a few weeks, right before Christmas, McKinley will go from talking head in a news story to the subject of one. “Cop gets emotional recounting homicide scene,” the Courier-Journal read. Having spent several hours with McKinley at this point, I was surprised. Her mood always appeared stable, rigid, like she’s never needed to let out a giant, calming exhale. I will watch the press conference. “I kind of want to paint this picture for everyone on how this happened …” she’ll start, going on to describe puddles and Christmas lights and reflections and the chaos of the police radios. “And then you have a five-year-old boy standing next to his dad, the man he calls his dad, taking his last breath. And the five-year-old little boy is crying....That’s not OK.” She’ll gnaw on her lower lip, swallowing hard. Tears won’t form. But the mother of two will seem shaken, like someone who’s weary of the cycle — the death, the details, the call 574-LMPD if you have any information. She wants people to pay attention. (She and some detectives will load up a Target cart with Christmas gifts for the five-year-old.)

McKinley updates me: The car’s already been located. “It was a stolen vehicle,” she says. Looks like there are good fingerprints. “Putting someone in that car is difficult,” she adds, clutching her phone. Still, it’s better luck than yesterday. The car believed to be involved in the Park Hill shooting was ditched and burned. “They destroyed the evidence,” she says.

Dusk settles in. White Christmas lights wrapped around a tree pop on. A school-age boy opens a window, leans out and places his chin on his arm. A skinny cream-colored kitten trots toward the body, only to halt inches from Burton’s red sneakers and scurry away, sliding through the bars of an iron fence.

Police radios beep and chatter. Another call of shots fired. “Fourth and Chestnut,” the dispatcher reports. A young female officer laughs. “We would’ve heard that!” she says. “People are calling in fake runs to keep us from somewhere.” McKinley nods. It happens all the time.

By about 6 p.m., the coroner zips Burton into a black body bag. The young boy in the window ducks back inside. Police tear down the yellow tape tethered to concrete pillars and gates, wadding it up and tossing it into a dumpster. As the scene clears, Beecher Terrace exhales. Children still in school polo shirts and khakis stream outdoors from the buildings that surrounded the body. One young girl breaks into hip-hop dance. Two others, about the same age and wearing only long-sleeve shirts in the sub-40-degree weather, cling to a fence and swing their bodies like pendulums back and forth.

I ride from Beecher Terrace with detective Jody Speaks, a compact man in his early 30s with a closely shaved head and glasses. He’s the kind of guy who won’t say the wrong thing to someone taking notes. And that may be why he’s been selected as the detective I’ll stick by for the night. We arrive at LMPD headquarters and climb stairs to the offices of homicide detectives. LMPD headquarters’ lobby glistens just fine, but head to the second floor, where homicide detectives cramp together. Paint chips off cream-colored concrete-block walls, exposing a former life of sea-foam green. Aggressive fluorescent lighting, some of which flickers behind the whirl of ceiling fans, does not flatter the scuffed 1950s-era building.

Speaks sits at the end of a narrow room lined with desks for some of the 16 homicide detectives. (In addition to the 16 detectives assigned to investigate deaths, the homicide unit has three cold-case detectives, three missing-persons detectives and 10 officers dedicated to nonfatal shootings.) Behind each desk, a bookshelf and a bulletin board. Like nearly all the bulletin boards, Speaks’ board holds pictures of his children and a photo of the homicide unit.

Just next to Speaks’ desk is a conference room. “We’ll go in there for debrief,” he tells me. After each homicide, detectives share what witness intel they were able to gather. Ten detectives slide into puffy gray office chairs and sit one-two-three on a brown couch. The predominant wardrobe: dress pants, tie and fleeces. A book, Hints and Tips to Make Life Easier, sits at table center. Awards line a wall. A few detectives grab Orange Crush sodas out of a fridge. They flip open their spiral notebooks. A near-unanimous chorus of “nobody saw anything” follows.

But detectives don’t work in isolation. There are informants and Crime Information Center officers who scan Facebook messages and social-media taunts. Theories bounce around the table — retaliation and dope dealing and bounties, and will there be more? I can’t share specifics, but just as a rowdy conversation begins about whether or not the body count will rise, a long beep from a police radio interrupts. Everyone hushes. Dispatch: Shots fired. 25th and Burwell. They listen. A man in a car — shot.

“Maybe it’s a suicide,” a detective on the couch says.

Dispatch clarifies: The man was driving and has run his car into a house.

“He was driving; it’s not a suicide,” the same detective says, reluctantly.

“You’re up,” a male detective says to a tall African-American female. She gives a knowing nod. It’s her turn in the rotation to take on lead investigative duties. Speaks grabs an Oatmeal Creme Pie. A tall sergeant puts on his brown dress coat. A voice calls out as everyone rises to leave for the crime scene, the second homicide of the night, number 110 with a whole month left in 2016: “You know, this is the record-breaker.”

Speaks and I are stuck at a train crossing a few blocks from the crime scene. Over high-pitch screeching and rumbling, I ask him why he thinks this year turned so violent. “I don’t know,” he says, shaking his head. “We all wrestle around with it.” Before coming to homicide two years ago, Speaks worked as a patrol officer in the division that covers Portland, Russell and downtown. He noticed shooting victims and suspects were getting younger. “There’s no structure in their life and no authority. Why would I respect anyone if I don’t respect myself?” he says. “I think some of these kids don’t understand that if you shoot someone you kill them, as crazy as that sounds. And guns aren’t that hard to get.”

A few days later, I’ll meet a 27-year-old who puts it this way: “You can get a gun as easy as you can get a toothbrush.” In 2016, LMPD’s Ninth Mobile Division, a unit that targets high-crime areas and is charged with getting guns off the street, seized 536 weapons, up from 490 in 2015. Of the weapons seized in 2016, 194 were taken from convicted felons, 39 from juveniles. The most frequent gun seized? The 9 mm pistol. It’s accurate, reliable. (Law enforcement prefers it too.) A 26-year-old who grew up in and still lives in Shelby Park says that when he was a teenager, sure, guns were around. “(But) there was never a time when our whole crew had guns,” he says. “You can see now six young cats and they all got guns, ages 14 and up. That’s scary.”

Some people avoid the gun stores and pawnshops that require background checks and rely on individual sellers, who can legally sell to whomever they please, no background check needed. Some share guns. Some steal guns. Homicide detectives were able to tie one gun to nine shootings this past year.

Speaks parks his cruiser and ducks under the police tape. “All your rounds are here,” an officer informs Speaks, pointing to shell casings lying near the curb of a sidewalk. The victim, still in the driver’s seat of a silver sedan, is down the block. Upon being shot, the 27-year-old black male victim struck a telephone pole, nearly snapping it in half, and then rammed into a house across the street, mangling the front of the car. One detective raises his arms, as if he’s holding an assault rifle, and runs through angles — did shots come from up high? From the sidewalk? Speaks kneels down to look at the casings. They look awfully familiar to those left behind at another recent murder.

Six years ago, Speaks was shot while working undercover. The bullet snuck in the small gap beneath his bulletproof vest and above his waistband. The shooting wasn’t as bad as the surgery that sliced him open so doctors could check for organ damage. “I feel like it aged me by about 10 years,” he says. According to the Courier-Journal, the shooter mistakenly got released from prison on parole in 2012 but is now back in prison after being arrested again on gun and drug charges.

Many officers have frustrations with the justice system. Speaks doesn’t say this. And many won’t publicly voice it. But here’s the problem: Police will meticulously build a case, collecting evidence, begging for witness cooperation, all in hopes of putting dangerous criminals behind bars. Those suspects get in court and suddenly a judge will administer a sentence with the weight of a “time-out.” As of mid-December, 41 of the homicide victims were convicted felons; 30 of the suspects arrested were convicted felons.

Speaks walks around the victim’s car. Bullet holes smaller than dimes dot front to back. Blood has dried in crimson drips down airbags and the body sits slumped toward the passenger side. Whoever did this unloaded a whole lot of gunfire. The whole thing probably took seconds. No one saw anything. McKinley decides to have the car towed (with the victim in it) for processing in a garage — better lighting, more controlled environment, warmer. The auto-theft garage is full, so a tow truck pulls the car back to headquarters and maneuvers it into a parking spot just two slots over from where chief Steve Conrad parks.

But even before the car is towed to the lot, a few detectives at headquarters stir. The detective who sits next to Speaks is convinced he knows the victim. Names are thrown out. Motives too. The detective pulls up Facebook, looking for R.I.P. posts. “Is this the guy?” he asks Speaks. “We don’t know who it is,” Speaks says. “His face is gone.”

Processing the car will take until 4 in the morning. There will be fingerprint kits and rods with lasers on the end that are stuck in the bullet holes to see the angle from which the killer shot. A can of aerosol fog will be sprayed at the green laser beam for pictures. The coroner will eventually release the victim’s name — 27-year-old Fernandez Bowman. The record-breaker.

A few hours with detectives on this night and the sheer volume of 2016 becomes obvious. They can’t find any more black folders. Let me back up: During a homicide investigation, detectives use black folders to keep track of paperwork — witness statements, coroner’s reports, etc. Green folders indicate a death investigation, like a suicide. Tonight, they’re so low on black folders they have to go digging around in drawers.

Detectives who used to tackle two or three cases per year are now assigned to six or seven. “You’re so busy you feel certain cases can’t get the attention they deserve,” Speaks says. “That eats at us because we want to solve everything we get. We take pride in our work. The most gratifying thing is to call up a family member and say, ‘Hey, we locked someone up for the death of your loved one.’” (By year’s end, 65 of LMPD’s 118 homicides will be cleared, a rate slightly lower than the national average.)

Chief Conrad and Mayor Fischer spend a lot of time convincing Louisville that they’re “tackling the scourge” (Fischer’s words). A controversial restructuring of LMPD will now target hotspots of crime and drug activity, Conrad says. There’s a new unit focused on community engagement. The mayor’s on board with hiring “interrupters,” folks with deep street ties that can hopefully mend conflicts before they end in gunfire. A new program called Pivot to Peace focuses on hooking shooting victims up with whatever resources they need, be it employment opportunities or therapy or drug treatment. It’s had success in other cities. So patience, please. We’re trying, Conrad and Fischer assure and reassure.

The radio chirps again. Shots fired near Beecher Terrace. All units advise, possibly an AK-47. A lanky, animated sergeant with a demeanor that, at least tonight, is just shy of boiling, bellows, “Open the windows!” as he flies up from his desk. “Maybe we can hear it!”

McKinley walks in a few minutes later, her hair pulled back in a ponytail, her hands shoved into her black coat’s pockets.

“Hey, lieutenant, we have another one,” a detective says.

“Really?” McKinley says in a flat tone.

“No, I’m just kidding.”

Another detective grumbles sarcastically that maybe if he picks up a homicide before Christmas, “I can spend time with my family” on the holiday. The unit relies on humor, often dark humor, but humor nonetheless. When the call went out for the murder at 25th and Burwell, groans gave way to jokes: “I’m sick of FaceTiming with my daughter!” “I’m on a milk carton.” “My wife’s gonna divorce me.” “That’s why we’re always hanging out together. We can’t go home!”

To me: “Anne, you drink?”

Me: “Oh, yes.”

Them: “Welcome to homicide.”

It’s about 10:30 now. A college football game plays on a television mounted to a wall near the conference room. Debrief on the record-breaker will take place in a few minutes over Spinelli’s pizza. A middle-aged detective holding a soda can stops to look at the game for a minute. Then he turns to me. “This is how the rest of Louisville lives, to be honest,” he says. “Ain’t no sugarcoating it — three murders in two days.”

Triple-digit body count. It doesn’t surprise those who’ve been in the thick, paying attention. I’m sitting with Young Commercial, a rapper and party promoter who was born Shermonte Mayfield and prefers to go by “YC.” We’re at a Roosters restaurant on Dixie Highway. Just water for him. He’s here to “tell it like it is,” says his friend and well-known community activist, Christopher 2x, who sits with us.

The truth, YC says: East versus west, Victory Park gang versus the E-block gang of Smoketown — all the this-hood-against-that-hood is pretty much background noise. “Turf don’t matter,” YC says. Partly because most of the housing projects have been torn down, everyone’s mixed in. There’s a whole lot of neighborhood pride and, yes, some wear colors to represent their neighborhood. But, as I’ll hear from another young man, “People within their own hoods don’t like each other.”

Gangs are now loose, changing constantly, dozens of cliques. Conflicts erupt quickly. Blame social media. Posting a taunt or challenge is basically drawing a pistol. If you disrespect the dead, especially someone who was well-respected — boom, it explodes. YC explains the mentality: “He is my op (opposition); I don’t care nothing about his life.” It escalates back and forth, back and forth, bullets passed around like an infection. “They’re not going to war over drugs,” YC says. “They’re going to war over bodies, a score, a count.”

Sometimes the innocent get caught in the middle. Just before Christmas I meet Anna Wheeler, a sweet and small 63-year-old with large, wet eyes who lives in Parkway Place. In early December she was watching TV in her apartment, around 8:30 at night. Gunfire exploded. “They were shooting at some dude; they done shot up my crib,” she says. She hit the concrete floor, bruising her hip. Since then, she’s been too scared too sleep, too scared to go to her mailbox most days. She holds her hands apart, leaving a five- or six-inch gap. That’s how much mail had been stuffed in since last time she got up the nerve to walk to the row of mailboxes. “There’s so much violence up here, it’s pitiful,” she says. Her doctor recommended a sleeping pill to calm her down at night. “I said, ‘You can’t put me on no sleeping pills. You’re too deep under (on sleeping pills). They get to shooting again, I got to stay alert!’”

Wheeler is one of many who wants more police. Not just the reactive type, but the proactive, the officers who are there chatting when all is calm. One longtime LMPD officer told me that when she retired a few years ago, the ill relationship between police and these high-crime communities was at an all-time high. National anger over deaths of unarmed black men likely have fed into that.

Christopher 2X states the perception of police plainly: “I got no reason to be trusting them,” he says. YC adds, “Police need to have people who can totally relate, get into the mindset of these youth.” Both men agree that this homicide spike is way bigger than just drug dealing. There’s “no money” in dope dealing, YC says. He should know. He’s been arrested three times for drug offenses, one for trafficking “heavy heroin.” And he’s got a weapons charge. “I’m a work in progress,” he says the first time we talk on the phone. But it’s hard to progress as a felon. No one wants to hire him. For most young folks, if you’re selling, you’re doing it because that’s what you know how to do; it’s what your friends and family do, YC says. Once on that pathway, violence isn’t far behind.

I wanted to go into Louisville’s Youth Detention Center and talk to kids about murders in 2016, especially since I heard constantly how much younger the suspects and victims were becoming. I was denied. But Yvette Gentry, who oversees Youth Detention and is Mayor Fischer’s chief of community building, told me about a recent visit with the juvenile inmates.

She started with an exercise to open them up a bit. “One of the questions I asked them was, ‘What was your most prominent emotion when you committed your crime?’” she says. “The first one they said was, ‘hurt.’” A few kids had lost parents to overdoses, others had friends or family who had been murdered. “The second (emotion) they shared really shook me a bit,” she says. The kids stated they were “hungry.”

“Physically hungry?” Gentry asked. “Some said yes, or just they needed to do some stuff. I had one kid that was, like, ‘I committed a robbery because I needed $180 because my brother needed a physical. He’s a good athlete and he needed a physical.’”

In talking with more than 20 people for this story over two months, one word kept surfacing — trauma. Kids who witness violence or feel its simmering threat are still kids. They don’t know how to name any sort of cause or effect. “Trauma is part of the culture,” one 29-year-old who grew up around drugs and violence told me. “For a long time, I didn’t even know what trauma was, I endured so much of it.”

Michelle Sircy, a grief counselor at Jefferson County Public Schools, says kids exposed to constant violence — in their neighborhoods, on social media, on the news — are full of anxiety and fear. “Whenever we find a weapon in school, it’s almost universally a child that says, ‘We were afraid to walk home from a bus stop.’”

One story from Sircy that I can’t shake: Two years ago a boy came to school in a daze, resting his head on his desk after he’d completed some testing. Sircy was in the room helping with administering the test, and she noticed the boy’s drained appearance. “I asked (the) young man if he was OK. His stepbrother had gotten killed,” Sircy recalls. “And I asked him, ‘Why are you here?’ He said, ‘Where else would I be?’”

Lee’Vaughn Morris has never lived outside Shelby Park, except for when he went to college. And he could’ve probably used his undergrad business degree for a desk job. The 6-foot-3 Morris, who played college basketball at Asbury University in Wilmore, Kentucky, could’ve probably chosen to ride out the next few years with a coaching gig. But when his best friend, Kei’andre Grinstead, known as “Drizzy,” was murdered during a robbery in February of 2015, he couldn’t let it go. Grinstead was a University of Louisville student, a popular kid in the Shelby Park/Smoketown neighborhoods, an area many in the black community call the “East End.”

Some mourned Drizzy’s death by calling themselves the Drizzy gang. Morris helped start a nonprofit called HOPE BY HOPE (Helping Our People Eat by Having Opportunities and Providing Empowerment). “Instead of being one foot in and one foot out, (I was) all in trying to do the community right,” he says.

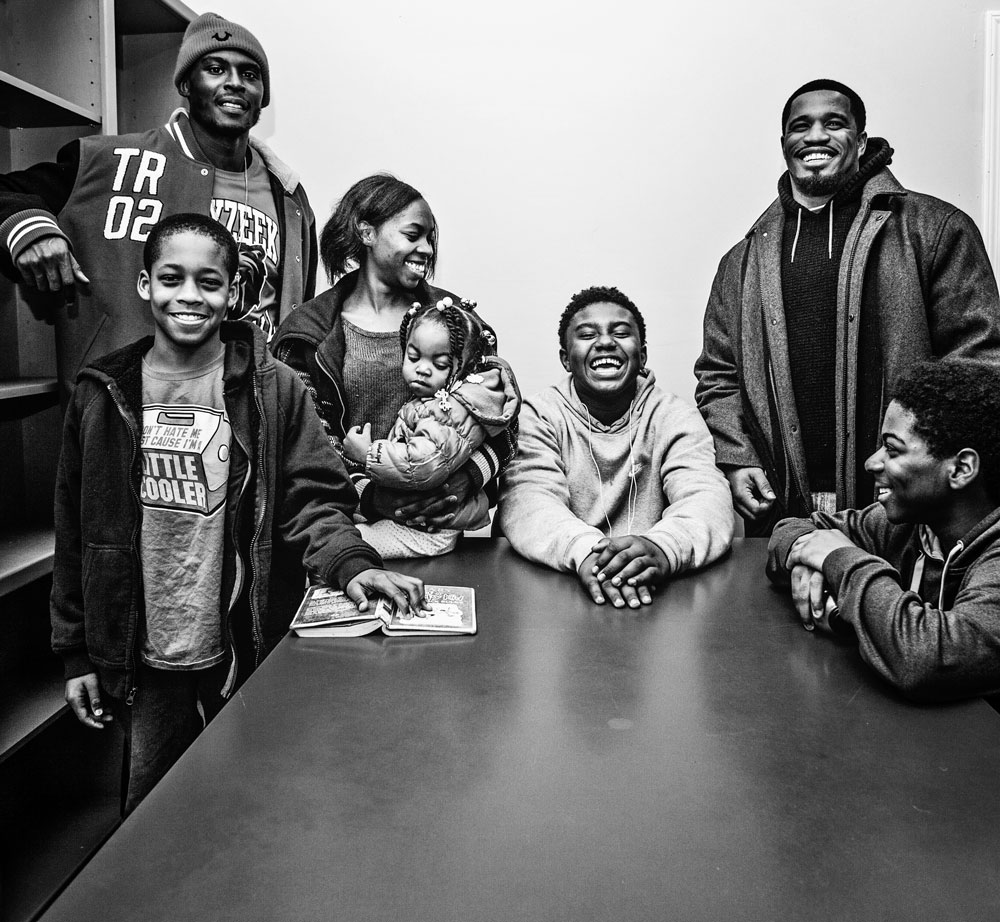

Lee'Vaughn Morris and other participants in HOPE BY HOPE's Smoketown office

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Morris rubs his hands to get warm, get to business. He sits in a chilly Smoketown office with a long red table, orange bookcase and not much else. To his left sits Yusuf Bibb, a 29-year-old with a stud nose ring and a bushy beard that hides a strong, square jaw. They’re meeting to fill out an application for city funding so that HOPE BY HOPE can grow into an after-school enrichment and mentoring program.

Right now, the organization mostly hinges on efforts Morris makes to mentor up to 10 kids, ages seven to 13. Six of them right now are one room over, eating pizza and Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, playing on their phones and wrestling. Every Sunday Morris tries to take them to church. He quizzes them on spelling words, coaches their youth basketball leagues, and when they run out the door to play ball, he’s yelling, “Where’s your coat?” Around his neck, Morris wears a homemade military-style dog tag with the pictures and names of three “little brothers” who died this year — Fat Daddy, 18-year-old Cameron Pugh, or “Cam,” and 22-year-old Larry Brewer. All lived and died not far from this office.

Bibb and Morris have mission statements to hash out and budgets to devise, but they’re caught up talking about a news story they saw — a guy who racked up eight trafficking charges in eight years.

“How do you stop that?” I ask.

“Divine intervention,” Bibb jokes, sort of.

His first arrest came at 12 years old after he stole clothes that he needed. There were a lot more arrests and prison time after that, most recently for possession of a firearm by a felon and trafficking marijuana. “It takes a person to reach their low. You have to be disgusted with what you’re doing,” says Bibb. “You have to want it for yourself.” Morris clicks his cheek, his way of nodding in agreement.

Bibb has lost several friends this year to homicide. The 98th homicide victim of 2016 called Bibb a few days before he got shot, asking how to get out of the streets. (Bibb and Morris both work as community organizers for the Urban League.) But before Bibb could figure out what calls to make on his friend’s behalf, the man got shot at Beecher Terrace.

HOPE BY HOPE is among many groups across Louisville trying to mentor and support kids. But Morris and others I speak with say it’s still a patchwork. Programs either find those in need or it’s the Yusuf Bibbs who are ready for change and seek it out. In a lot of neighborhoods there’s no obvious foundation or safety net. The Presbyterian Community Center in Smoketown once filled that role. Sharonda O’Bannon-Morton, a longtime JCPS teacher who worked with troubled youth at PCC back in the ’90s, says the basketball gym was a great place to learn about conflicts. “I’d just be listening in the gym. It wasn’t snitching, just listening,” she remembers. If a fight was brewing, she’d step in. “You got an idea of what was needed in the community,” O’Bannon-Morton adds. In 2013, when the Sheppard Square public housing complex was demolished to make way for mixed-income housing, PCC closed. All their clientele had been relocated and it was unclear how many would return to the tidy new townhomes.

Morris carefully writes HOPE BY HOPE’s five “E’s” into a narrow answer box on the application paperwork: empower, engage, educate, endure, encourage. Stopping gun violence will demand consistency, he believes. “Right now, it’s big. But if God makes a miracle and next year there’s only 20 murders in the first few months, it’ll go away. But every day” — he pauses to tap his knuckles on the table in the cadence of gunfire — “I’m gonna hear gunshots.”

Under the 93-degree, late-August sun, Angela Pugh Williams calls her son’s phone. No answer. The 1000 block of Hancock Street is sectioned off with crime-scene tape. Williams stands behind it, worried. Just after 3:30 she had received a frantic phone call from her daughter. “Larry’s been shot.” Twenty-two-year-old Larry Brewer, a lifelong friend of her son, Cameron Pugh, had been gunned down in a drive-by. If that wasn’t enough to get Williams’ heart racing, her daughter added, “Cameron was with him.” The three of them were hanging out in Shelby Park just before the shooting, like they’d done nearly every day since they were elementary kids, cutting through the park to catch the bus or mess around after school.

Again, she calls her son’s phone. Still ringing. Maybe he ran off and dropped his phone, she thinks. Williams gives a description of her son to a detective — light-skinned, 5-foot-6, curly black hair, slim. To less official types, she’d probably go on about his smile, a dimpled, fantastic grin that got him out of trouble as a young boy and maybe into some trouble too. But this was police. “Wait here,” she recalls the detective saying. Twenty, maybe 30 minutes pass. Nothing. So she leaves to go pick up her older son from work, convinced her youngest child in no way could be part of a homicide. My son doesn’t have no problem with anybody, she tells herself.

Then, a call from Pugh’s father. “Where are you?” he asks. She returns, panicked. The 39-year-old with black hair and blue-green eyes slips under police tape. Uniformed arms hold her back. Someone comes over. “Are you going to be OK?” A picture on a phone. “Is this your son?” There on the screen is the hourglass timer tattooed on her youngest child’s right arm.

A relentless wind swirls around Williams. Goosebumps dot the back of her neck. Stray hairs escape her bun and flap at her cheek and chin. She stands near her son’s gravesite on an unseasonably warm January day. Gusts shake a line of red, sparkly bows and bundles of red and white artificial flowers that brighten the muddy mound. She’s still working on a headstone, still paying off the couple thousand dollars she owes the funeral home. She leans over glittery red letters that spell “Dino,” a nickname. “Prince Dino, that’s what his friends called him,” she explains, though she’s not sure why. Williams straightens an “N” and “O” knocked sideways by the wind. He wasn’t Dino to her. Just Cameron. Cameron Davon Pugh if she was mad.

Pugh’s buried in a cemetery on Newburg Road near a tiny creek, at the base of two perfectly sculpted green slopes, just to the left of Williams’ dad, who died 13 years ago. When Pugh would visit his grandfather’s gravesite as a kid, he’d roll down those hills, gathering speed, laughing. “Never, ever, would I have thought this,” Williams says, looking at the ground. Pugh’s death is one of more than 50 unsolved murders of 2016. All Williams knows is it was a drive-by. Brewer got shot first, she says. Her son ran, jumping a fence. The bullets traveled faster.

The shock of seeing that hourglass tattoo still hasn’t subsided. In the moments right after, she remembers the screaming and crying, the way the world felt smudged, suffocating. It was too much. An ambulance took her to Jewish Hospital. “They told me I was almost ready to have a stroke,” she says.

And when she remembers that day, she nearly always relives the night before. Williams works third shift at a hotel doing night audits. On her break, she went to pick up Pugh and a friend. She dropped them off at her house. “Keep the house clean because the cable company is coming in the morning,” she told them. “Don’t make a mess.” Pugh held the door as he got out. “I won’t, mama,” she remembers him saying. “That’s what he always said — mama. Everything was mama. And he said, ‘I love you.’ And I said, ‘Shut the door.’ He said, ‘I said, I love you.’ I said, ‘I love you too.’”

Her next goodbye would be next to a white casket, taking pictures of her hands holding his hands, savoring one last head-to-toe look — hair in two braids, white button-down, a picture of his best friend who was murdered the year before tucked near his waist. The chemical smell of glue or makeup or whatever they use to paint life into corpses still lingers. So does that image. “I close my eyes and I see him in that casket,” she says.

Angela Pugh Williams at her son Cameron's grave

There are rumors out there as to why Pugh was gunned down. One involves a confrontation in the hours after a murder the day before in Smoketown, the one that killed 14-year-old Troyvonte Hurt, aka “Fat Daddy.” (Detectives are still investigating and won’t say much.)

Williams wants to know the why. And she really wants me and anyone reading this to know that no matter the why, there was a good kid that got killed. One evening over coffee she opens an envelope of pictures. There’s one of her son, maybe four or five years old, with no clothes on, sitting on a brown carpet as his older sister puts makeup on him. Another picture shows him splashing at a water park. And there he is in his skating phase — thick-rimmed black glasses, short hair, goofy dimpled smile. He grew up in a two-parent, loving household, she says. Williams has always worked and her other two kids graduated high school and hold steady jobs. So this isn’t a tale of just another poor gangbanger — she wants to make that clear.

Pugh had hung out with Larry Brewer and the same group of kids since forever. “They were not troublemakers. They just hung out in Shelby Park,” she says. “It never really worried me that they was together.” At 15 years old, Williams noticed a change. The boy who was “always up under her” retreated, blocking her from his social-media accounts. He got into girls and became a young father. Demi, now three years old, has Pugh’s dimples, ringlet curls and, maybe, his wild side.

Pugh once fled police in Shelby Park on one of those mini-motorcycles. He’d talk back to teachers sometimes and he dropped out of Atherton High School. But Pugh worked at a KFC with Brewer. And he adored his little girl, reserving Sundays for playtime. Williams says she and her son would watch hours of home-renovation shows together on the couch. Pugh decided that was his future — flipping houses for a living. First, let’s work on getting your GED, Williams advised him.

Cameron with his daughter, Demi

A little more than a year ago, one of Pugh’s best friends died after an accidental shooting. Pugh tattooed his friend’s name — Adrian — near his temple, trying to hide it from his mom the day he did it. Sometimes in pictures he would hold up his fingers to make an A.D., a tribute to his buddy. On Pugh’s Facebook page there are photos quite different from the ones in his mom’s envelope. Like one that shows him with pistols shoved into his jean pockets as he poses in a neat, cozy kitchen with floral curtains and fruit-patterned towels.

Williams says she didn’t see these pictures until after his death. If she saw signs of gang culture, like the colors he stuck to wearing, she thought he was just mimicking a lifestyle, acting tough. “If I really thought that was his reality, I would’ve fought,” she says. “I just thought it was something they were trying to portray. Does that make me a bad mom?” When she won $2,700 in the lottery, what’s the first thing Pugh did? Flash the bills for a picture and posted it on Facebook. “You can see how fast that image (can be) twisted,” she says.

Pugh was dressed in a black T-shirt in the first dream just days after his murder. There were no words, no background. It was like he was hanging in space. He gave Williams a hug and disappeared. “My (oldest) son had the same dream,” Williams says, bewildered. After that, Williams told herself that, should he appear again, to make sure to ask him questions. On Nov. 7, another dream. There he was, sitting on the edge of her bed eating cake. “Who did this to you?” Williams sat up and asked. A boat came and took him away. He hasn’t visited her since.

She visited a psychic. Maybe he could tell her who did it. The fact that no one has come forward with information infuriates her. “You tell me at 3:30 in the afternoon — that’s when you have school buses and people coming home from work and people going to work — somebody seen something,” she says. “But they’re that scared. They won’t say anything.”

Williams calls the lead detective on her son’s case often. Sometimes she gets a little heated. She just wants answers. The psychic told her March would be an important month. Maybe that’s when the killer will be arrested, she thinks. The other day, she sent a text to the detective: “PLZ help us. It’s been almost 5 month and we miss him so much.”

The first time Demi visited her dad’s gravesite, she pushed her little pink princess stroller, a blond baby doll strapped in for a couple loops around headstones. She played on the hills. Just as her dad had done some 13 years ago. “If we give daddy’s boo-boo a Band-Aid, will he get up?” she asked Williams. Demi will struggle with her father’s death twice. Once, as a toddler who doesn’t get it, who goes to the cemetery and asks, “Well, where is he?” But in a few years, when death, its permanence, settles in, she’ll have to process the loss, not just the absence.

On warm days, Williams will fold out a lawn chair and sit. “(We) just talk,” she says, tears welling in her eyes. She turns her face into the day’s fierce wind, trying to stop the cry. Williams’ pain is still raw. “I’d never wish this on anybody,” she says to me on a couple different occasions. And as we walk back to her car, she talks about the other teenagers she’s noticed buried near her son. A 15-year-old here. A 13-year-old there. She does what aching mothers do — a balloon release on Christmas, heartfelt pleas on television for justice, comforting other mothers who’ve also lost children to gun violence.

Grief isn’t logical. She’ll cry while crunching numbers at the hotel overnight. (“Good thing I work alone,” she jokes.) She’ll sit through three sessions at a tattoo parlor to get an ornate tribute — Pugh’s face with sun beams behind it, roses on the left, a dove on the right, his birthdate (1/24/98) just beneath a clock set to 6:04, the time he was born — that stretches nearly shoulder to shoulder. But she’ll then strip the walls of any pictures of him. “It’s too painful to look at them,” she says. Reminders persist. On this January morning, just before coming to the cemetery, she turned on the television to news of Louisville’s first homicide of 2017, an early-morning stabbing. Williams sat on the edge of her bed. “And so it begins,” she said.

This originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of Louisville Magazine. To subscribe to Louisville Magazine, click here. To find your very own copy of Louisville Magazine, click here.