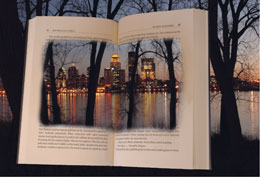

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to live in one of those mega-storied American neighborhoods like Chicago’s South Side or San Francisco’s North Beach? What a kick it would be, to pick up one of the many novels set in those locales and read about places and people as familiar as your own back yard — yet see them in a new light, through the eyes of a fiction writer.

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to live in one of those mega-storied American neighborhoods like Chicago’s South Side or San Francisco’s North Beach? What a kick it would be, to pick up one of the many novels set in those locales and read about places and people as familiar as your own back yard — yet see them in a new light, through the eyes of a fiction writer.

Well, lately, I’ve gotten a taste of that insiders’ edge, that sense of seeing my hometown through a literary lens. One place I found it was on the pages of Louisville writer Kirby Gann’s 2005 novel Our Napoleon in Rags. By its third page, any careful River City reader will have readily recognized a number of landmarks and luminaries. Pseudonymous names like Montreux and Olde Towne notwithstanding, readers will easily identify the novel’s setting as Louisville, and more specifically as the richly diverse and colorful neighborhood known as Old Louisville.

My bet is that readers of a certain age or lifestyle will also quickly spot our legendary Old Louisville tavern, the Rudyard Kipling, as the beau ideal for Gann’s fictional saloon, the Don Quixote, an urban haunt described in the book as a "sumptuous dive," where most of the story’s action takes place. So, too, will readers discern among the eccentricities of the Don Quixote’s unconventional owners, Glenda and Beau Stiles, some of the better-known attributes of The Rud’s true-life proprietors, Sheila and Ken Pyle — right down to Sheila’s mountain roots and musical talents.

For hometown readers, Gann’s story weaves together tantalizing bits of Louisville political and cultural lore, albeit manipulated for narrative purposes, and adds a dash of doctored-up local notables, creating a story that is, at once, a fantasy all its own and a slyly familiar scenario.

Part of the pleasure in reading a book like Our Napoleon in Rags, or Mary Welp’s The Triangle Pose (another 2005 novel populated by Louisville characters whose names may have been changed but whose personalities are unmistakably hitched to the wagons of certain recognizable public figures), is the opportunity it offers to observe, at a creative distance, the places and people who inhabit the city’s collective imagination.

This is not to say that novelists, particularly those with ties to the city, have not for some time been quietly decorating the literary map with arrows aimed squarely at Louisville. Alice Hegan Rice (Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch) and Gerald McDaniel (the Aindreas series) have set stories in Louisville’s historical neighborhoods, while romance and mystery writers Karen Robards, Sue Grafton, Taylor McCafferty and Beverly Taylor Herald have all, at one time or another, used Louisville as settings.

But, most famously, it was F. Scott Fitzgerald who chose our fair city as the place where Daisy Buchanan, erstwhile Belle of Louisville, met her match in The Great Gatsby. In one of literature’s most memorable flashbacks, Gatsby and Daisy meet just before World War I against the backdrop of the now-defunct Camp Taylor, where Gatsby was stationed. Fitzgerald placed Daisy’s subsequent wedding in the ballroom of a hotel modeled after the Seelbach Hotel (which, by the way, was called the "Muhlbach" in the novel’s first printing, but was restored to "Seelbach" in later editions).

Fiction writers are infamous for sticking to the truth when it behooves them and then, when needs be, cross-dressing facts as fantasy. That’s the art of storytelling. Gann’s novel, a case in point, is set in a figurative Louisville, a town modeled after the real thing but given a mythical name, Montreux. And yet, despite the novel’s refusal to own up to its own exemplar, it stands out to me as a story that is quite specifically "about" Louisville — historically, culturally, geographically. In fact, Gann says he’s heard it described as "a secret history of Louisville."

When I asked him why he didn’t just ’fess up to his setting, call it Louisville and scrap the alias, Gann said the decision to call it Montreux was all about creative "freedom."

"I didn’t want to risk people reading the book and saying, ‘It’s not like that; I live there and I know.’ So I made a city that’s a skewed version of the city I know best," he said. None of his characters are one-to-one correspondences with real people, he said.

Maybe so, but few of us can resist reading folks we know into characters in books — even when those characters are not traipsing through our hometowns. I admit to deriving a provincial pleasure from passages evoking the dogwoods and cast-iron facades and restaurant rows of Louisville — rather than, for the umpteenth time, revisiting the famed stoops of Brooklyn, the celebrated streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown or the oft-chronicled cafes of New Orleans’ French Quarter. There’s a delightful shock of recognition that comes from reading a scene in which a young man rents an apartment not in Chelsea or Soho or Tribeca, but in our very own Crescent Hill — which is exactly what happens in Judge, Louisville native Dwight Allen’s novel based loosely on his life growing up the son of a local federal judge.

Another such moment in Allen’s novel comes at the /files/storyimages/of a description of a bridge game, a long breezy sentence that winds up with "friends talking about an art exhibit in Chicago or a dress bought at Byck’s or the Rever/files/storyimages/Alfred Lloyd Boyles over at St. Luke’s having to bail his sexton out of the drunk tank." Here, Allen has his authorial cake and eats it, too: Some real names are used; others are ever-so-lightly tweaked.

In The Triangle Pose, Mary Welp, whose "Dining In" columns appear in this magazine, has created a sharp-tongued, take-no-prisoners narrator in Anna Wallace, a Louisvillian who shares more than a few professional and personal characteristics with Welp herself, among them Anna’s predilection for eating (and writing about) good food. Readers sit down to dine with Anna at tables all over town, ranging from suburban chains (Red Lobster, Macaroni Grill) to elegant urban eateries that bear fictional names but identifiable attributes of some of Louisville’s choicest dining spots.

But the name-dropping in The Triangle Pose is not limited to culinary Louisville. The novel is a virtual tour of the city’s hot spots, with stop-offs at some of the metro area’s biggest draws, from Southeast Christian Church to Trixie’s strip club.

In Welp’s novel there is a passage that, to me, illustrates the gift that fiction sometimes bestows on reality, especially a reality we know so well that we may have stopped noticing it. Describing downtown Louisville on a night when the "sky was now clear, the moon replete and bluish-white," she writes of passing "empty warehouses and antique stores so ancient they were no longer in business, though they still held bits of brass and wood and china."

Of course, there’s also the flip side to seeing your hometown through a writer’s eyes: Sometimes the focus is on warts we’d rather ignore. Describing an enclave of "restored mansions" a few blocks from the Don Quixote, Kirby Gann contrasts the wandering urban homeless he calls "The Lost," with their gentrified neighbors:

"Desperately hip young lawyers and fund-for-the-arts economic developers and anti-Freudian existential psychoanalysts and the entire fey interior-design fetishists crowd preferred to keep to themselves behind gilded walls and sculpted cornices, protected by brick and iron barriers."

Humorous or dead serious, incisive or incensed, novels like these give us a way to take a step back for a better view of the place we live and love.

— Dianne Aprile